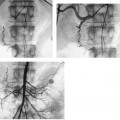

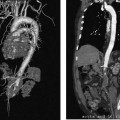

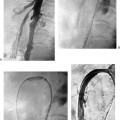

CASE 45 A 62-year-old female with end-stage renal disease was referred to interventional radiology for replacement of a malfunctioning permanent hemodialysis catheter. The dialysis technologist reported inability to withdraw blood from either lumen. Figure 45-1 A 62-year-old female with end-stage renal disease and a dysfunctional permanent hemodialysis catheter. (A) The catheter was removed over two stiff Glidewires (Boston Scientific, Natick, Massachusetts) and contrast was injected through a sidearm sheath. No passage of contrast into the right atrium is seen. There is retrograde flow of contrast from the SVC into the right brachiocephalic vein and opacification of a large mediastinal collateral vein. A linear, catheter-shaped filling defect within the SVC represents the fibrin sheath that caused catheter dysfunction. (B) Angioplasty of the fibrin sheath and SVC is performed using a 10-mm balloon. (C) Replacement of a functional permanent hemodialysis catheter. The catheter was removed over two stiff angled Glidewires (Boston Scientific, Natick, Massachusetts) advanced into the inferior vena cava. Venography was performed through a sidearm sheath showing no passage of contrast into the right atrium, retrograde flow of contrast from the superior vena cava (SVC) into the right brachiocephalic vein, and opacification of a large mediastinal collateral vein. A linear, catheter-shaped filling defect was visible within the SVC. Catheter dysfunction caused by fibrin sheath formation and central venous obstruction. A 10-mm balloon was advanced over one of the stiff angled Glidewires (Boston Scientific, Natick, Massachusetts) and repeatedly inflated throughout the SVC. A new permanent hemodialysis catheter was then placed and noted to flush and draw rapidly using a 10-cc syringe. Following the procedure, the patient underwent uneventful dialysis where excellent flow rates were achieved. Based on durability, convenience, and the risk of associated morbidity and mortality, tunneled catheters are a suboptimal source of permanent venous access compared with arteriovenous shunts. As a result, the National Kidney Foundation recommends that dialysis centers work toward the goal of limiting the use of catheters to patients awaiting shunt placement or maturation and patients who have exhausted shunt options. Acute complications of catheter placement include pneumothorax, bleeding, air embolus, central venous rupture, infection, and dysfunction. Chronic complications will usually occur with enough follow-up time, including dysfunction, infection, and central venous obstruction. This case discusses the management of chronic complications of permanent hemodialysis catheters. The incidence of chronic complications varies with the route of central venous access used. Despite repeated interventions in interventional radiology, patients requiring the extended use of catheters tend to exhaust central venous access options and require the use of progressively suboptimal routes, which include the jugular veins, recanalized or patent chest and thyrocervical veins, femoral veins, inferior vena cava (translumbar approach), and hepatic veins (transhepatic approach). Subclavian veins are typically reserved for patients who have exhausted options for upper extremity shunt placement to avoid catheter-related venous outflow obstruction. Regardless of the route of access, permanent chest catheters offer similar low rates of dysfunction and infection (Funaki). In comparison, femoral catheters are associated with an increased rate of infection (Zaleski), and both transhepatic and translumbar catheters are associated with increased rates of infection and dysfunction (Lund, Stavropoulos). In summary, permanent catheters are initially placed in chest and neck veins rather than alternative access sites to maximize catheter survival by minimizing chronic complications of dysfunction and infection.

Clinical Presentation

Radiologic Studies

Diagnosis

Treatment

Equipment

Discussion

Background

Route of Venous Access

Dysfunction

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree