Atypical cervicogenic headache

Cervicalgia

Carotid surgery

Thyroid surgery

Parathyroid surgery

Lymph node biopsy in the neck

Surgery on the mastoid process

Central line placement (awake)

Other head and neck surgery

Anatomy of the Cervical Plexus

The cervical plexus is comprised of three loops that arise from the anterior rami of the cervical roots of C2–C4 (Fig. 13.1). The loops of the plexus lie anterior to the levator scapulae and scalenus medius muscles and posterior to the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) [4, 5]. Deep terminal branches of the plexus innervate deep muscular structures such as the scalenus medius, trapezius, levator scapulae, and SCM and communicate with the spinal accessory nerve. The superficial branches innervate the skin over the lateral head and neck via the occipital, anterior cutaneous, great auricular, and supraclavicular nerves (Fig. 13.2) [4, 5].

Fig. 13.1

Anatomy of the cervical plexus. Diagram of the cervical plexus as it emerges from the cervical roots of C2–4. Note the close relationship between the cervical plexus and the phrenic nerve, which is usually affected by a deep cervical plexus block

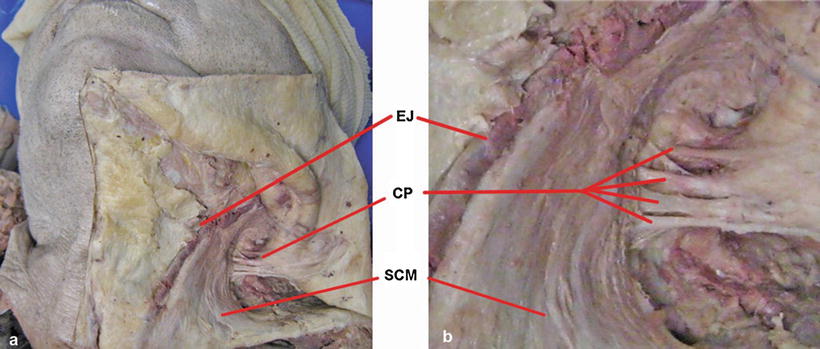

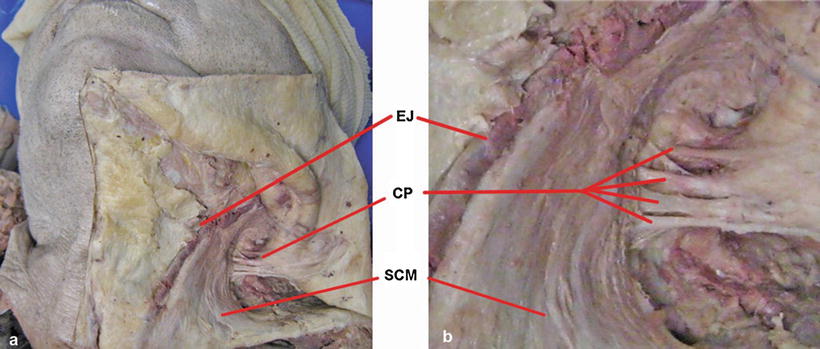

Fig. 13.2

Branches of the cervical plexus in situ. (a, b) Superficial cutaneous dissection of the left neck demonstrates the sternocleidomastoid (SCM), the external jugular vein (EJ), and the four branches of the cervical plexus (CP) emerging just posterior to the SCM. These branches are the great occipital, great auricular, transverse cervical, and supraclavicular nerves. In this dissection, the skin has been reflected posteriorly to the left (Courtesy of G. Matchett, made at the Gross Anatomy Lab at Stanford University School of Medicine)

Techniques for Blocking the Cervical Plexus

Cervical plexus blocks are usually classified as “superficial” or “deep.” Historically, a “superficial” block implied injection of local anesthetic into subcutaneous tissue without violating the fascial planes investing the SCM [6]. However, in current practice, a “superficial” block usually indicates administration of local anesthetic subcutaneously, around the SCM, and deep to fascial planes around the SCM [7, 8]. A “deep” block implies a plexus block at the level of the transverse processes of the cervical vertebrae [9]. Some have suggested the concept of an “intermediate” plexus block, defined by administration of local anesthetic subcutaneously and just deep to the investing fascial layers of the SCM [10]. However, as a practical matter, this definition overlaps considerably with what is currently known as a “superficial” block. In this chapter, we will use the term “superficial” to indicate an injection both in the skin and into layers just deep to the SCM as is commonly done today. A “deep” block refers to an injection at the level of the transverse processes of the cervical spine. A “combined” cervical plexus block usually refers to the combination of a deep and superficial block.

Although the cervical plexus may be approached anteriorly, laterally, or posteriorly, the most common practice today is an anterolateral approach for both superficial and deep plexus blocks (Fig. 13.3a–f) [4, 9]. The superficial block is usually performed at the midpoint between the mastoid process and the sternal notch at the posterior edge of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (Fig. 13.3a–c). Local anesthetic is injected along the SCM, just deep to the SCM, and in the general direction of the terminal branches of the plexus [4].

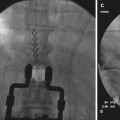

Fig. 13.3

Techniques for blocking the cervical plexus. (a) The superficial cervical plexus can be approached at the midline of the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) (dashed line). The SCM can be identified superiorly by the mastoid process and inferiorly by the sternal notch (+). (b) Needle passage for a superficial block should be superior, inferior, and just deep to the sternocleidomastoid (SCM). (c) In transverse view at C4, the needle should pass just deep to the SCM. (d) The deep cervical plexus block can be performed by three individual injections at C2–4 or alternately can be performed by a single injection at C3 or C4. Typically, the location for the injections is noted by palpation of the C6 transverse process (point x). The transverse process of C2–4 can be identified superiorly to C6 on a line drawn between the mastoid process and the C6 transverse process (dotted line). In an average adult, the transverse processes of C4–2 are approximately 2, 4, and 6 cm superiorly on the line connecting the mastoid process and C6. Once the transverse (superior tubercle) is contacted by the needle, the needle should be withdrawn 1–2 mm and local anesthetic injected following negative aspiration for blood. (e) Schematic diagram showing correct needle placement at C3. (f) Transverse section showing the transverse process of C4 (a, d – Reprinted with permission and adapted from Paul et al. [11]. © License from Wolters Kluwer Health License, 2009; b, e – Reprinted with permission and adapted from Stoneham and Knighton [12]. © License from Oxford University Press License, 2009; c, f – Reprinted with permission and adapted from the Visible Human Project of the National Library of Medicine – USA)

Deep CPB is traditionally performed with three separate injections at the transverse process of C2–4 [4]. Historically, this block is performed using surface and bony landmarks, although our preference is to use fluoroscopic guidance with injection of iodinated contrast to help confirm needle placement. The bony landmark for this block is traditionally the C6 transverse process. This can be palpated, and C4–2 can be identified on a line drawn between C6 transverse process and the mastoid process (Fig. 13.3d–f). Alternately, a single injection at the transverse process of C3 or C4 may be used [9]. Needle placement for the deep block may be facilitated by surface landmarks, elicitation of paresthesias, elicitation of muscle twitches from levator scapulae [13], ultrasound [14, 15], or fluoroscopy [16]. Studies comparing single versus multiple injection techniques have reported similar outcomes [13, 17].

Local anesthetic spreads easily in the compartments of the neck after a superficial CPB. This has been demonstrated by cadaver study (Fig. 13.4) and clinical experience [7]. Likewise, after deep CPB, local anesthetic spreads easily, especially when large volumes are given (>20 mL) [18].

Fig. 13.4

Spread of local anesthetic with cervical plexus blocks. Superficial plexus block with methylene blue dye administered just deep to the sternocleidomastoid in a cadaver study. Following injection, methylene blue dye is widely distributed in the neck. 1-Ear, 2-mandible, 3-sternocleidomastoid muscle, 4-internal jugular vein, 5-subclavian artery, 6-omohyoid muscle (cut), 7-brachial nerve plexus, 8-trapezius muscle (cut). The inset picture denotes the orientation of the cadaver (Adapted and used with permission from Pandit et al. [7]. © License from Oxford University Press License, 2009)

Indications: Surgical Anesthesia

The most common indication for CPB is surgical anesthesia. For example, the block may be used in addition to, or in place of, general anesthesia for carotid endarterectomy (CEA). Table 13.1 provides a list of common surgical indications.

Indications: Cervicalgia and Cervicogenic Headache

Historical interest in CPB arose out of a desire to treat cervicalgia arising from the cervical plexus [1]. A case series in 1955 reported the use of the block in 63 patients with atypical cervicogenic headache, 57 of who appeared to benefit from CPB [19]. Recent case series report similar findings. Goldberg et al. [16] described a 39-patient case series of deep cervical plexus block for atypical headaches that appeared to coincide predominately with a cervical or brachial plexus distraction-type injury. A majority of patients experienced a significant decrease in average pain scores immediately after the blocks, and a return to pre-block pain level took an average of 6.6 weeks [16]. Selective cervical plexus blocks may also be useful as an aid in diagnosis of atypical orofacial pain [20].

Choice of Local Anesthetic for Cervical Plexus Block

Bupivacaine and ropivacaine are commonly used for CPB, although nearly any local anesthetic can be used (Table 13.2). Pharmacokinetic studies have confirmed the safety of adding epinephrine to local anesthetic solutions for cervical plexus block [28–30]. This may help prolong the blockade and reduce serum concentration of local anesthetic [30]. Epinephrine may be associated with mild sympathomimetic effects on heart rate and blood pressure [29, 31].

Table 13.2

Sample protocols for cervical plexus block

Local anesthetic | Dose | References |

|---|---|---|

Superficial | ||

Bupivacaine | 0.375 %, 1.4 mg/kg (average = 30 mL) | [21] |

Bupivacaine | 0.375 %, 20 mL | [22] |

Levobupivacaine | 0.5 %, 1 mg/kg | [23] |

Levobupivacaine | 0.5 %, 0.35 mL/kg | [24] |

Ropivacaine | 0.75 %, 20 mL + clonidine 50 mcg | [25] |

Ropivacaine | 1 %, 10 mL | [26] |

Ropivacaine | 0.75 %, 1.5 mg/kg | [23] |

Ropivacaine | 0.375–0.75 %, 20 mL | [27] |

Deep | ||

Bupivacaine | 0.25 %, 3–5 cc per level (C2–4) | [4] |

Bupivacaine | 0.375 %, 20 mL at C4 | |

Bupivacaine | 0.25 %, 10 mL + 80 mg methylprednisolone (C2–4) | [16] |

Lidocaine | 2 % ± bicarbonate and epinephrine, (3–5 cc per level) | [4] |

Mepivacaine | 1.5 % ± bicarbonate and epinephrine, (3–5 cc per level) | [4] |

Ropivacaine | 0.5 %, 3–5 cc per level | [4] |

Combined | ||

Bupivacaine | 0.375 %, 1/3 of dose placed at C4 (deep), 2/3 of dose placed superficially, total dose = 1.4 mg/kg | [21] |

Levobupivacaine | 0.5 %, 0.2 mL/kg placed at C3, then 0.15 mL/kg placed superficially | [24] |

Ropivacaine | 0.375–0.75 %, 10 mL at C4 followed by 20 mL placed superficially | [27] |

Long-acting local anesthetics are usually used for CPB in order to ensure adequate duration of block (Table 13.2). Most comparative studies of one long-acting local anesthetic to another have reported similar clinical outcomes at equipotent doses [23, 32, 33]. Ropivacaine (0.75 or 1 %) was reported to be superior to mepivacaine (2 %) in the setting of deep cervical plexus block for CEA in one study [34]. Studies suggest that higher concentration local anesthetic solution (e.g., 0.75 % ropivacaine instead of 0.375 % ropivacaine) may be preferable for duration and density of block [27].

Reports have described other drugs such as clonidine [25] or corticosteroids [16] as part of CPB. The addition of clonidine (50 μg) to ropivacaine (150 mg) for superficial cervical plexus block was found to shorten the onset time and improve the quality of surgical anesthesia [25]. Steroids may be included for CPB in the setting of cervicalgia or cervicogenic headache [16].

Contraindications

Contraindications include patient refusal, marginal pulmonary status, severe coagulopathy, local infection, and severe anatomic distortion. Baseline pulmonary status is important to consider before a deep cervical plexus block. Deep blockade usually results in phrenic nerve paralysis with hemidiaphragmatic dysfunction, and this can potentially lead to respiratory distress in a patient with marginal baseline pulmonary function [4].

Complications

Blockade of the superficial cervical plexus is extremely safe and complications are very rare [35]. Most complications, serious or otherwise, occur with deep CPB [35]. A quantitative meta-analysis of 69 published reports covering more than 10,000 individual blocks found that deep CPB is significantly more likely to be associated with serious block-related complications and the need to convert to general anesthesia than superficial CPB (Fig. 13.5) [35].