Challenge

CASE 160

ANSWERS – CASE 159

Hepatitis

Reference

Kurtz AB, Rubin CS, Cooper HS, et al: Ultrasound findings in hepatitis. Radiology 1980;136:717–723.

Comment

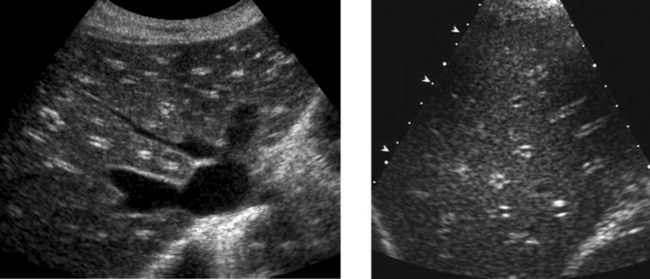

Except for fatty infiltration and, to a lesser degree, cirrhosis, ultrasound is not a good way of evaluating or quantitating diffuse liver disease. Hepatitis is no exception. Nevertheless, there are some sonographic findings that are seen in patients with hepatitis. Perhaps the most common abnormality is thickening of the gallbladder wall (see Case 13). In fact, hepatitis can produce dramatic gallbladder wall thickening. It is also characteristic of patients with hepatitis for the gallbladder lumen to be contracted. Another finding seen commonly is mildly enlarged lymph nodes in the porta hepatis, around the celiac axis, and in the peripancreatic area. Unfortunately, mildly enlarged nodes are very common in these areas and can be associated with many other inflammatory or infectious conditions in the right upper quadrant. They are also common in liver diseases other than hepatitis, such as primary biliary cirrhosis and sclerosing cholangitis.

ANSWERS – CASE 160

ANSWERS – CASE 161

Hepatic Focal Nodular Hyperplasia

ANSWERS – CASE 162

Biceps Tendon Rupture

CASE 163

Longitudinal view of the right upper quadrant and transverse view of the aorta and left upper quadrant in different patients.