Chapter 11 IMAGING OF THE HIP AND PELVIS

Imaging of the hip is a rapidly growing area of interest to orthopedic surgeons, especially with regard to dysplasia, impingement, labral tear, and groin injuries. This chapter focuses on newly emerging areas, issues in which controversy exists, and management conundrums that commonly affect the practicing radiologist.

MODALITIES

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

For patients with acute trauma, nondisplaced fractures may not be visible radiographically or even on CT. This is especially true in elderly patients with osteoporosis; the combination of low bone density, thin cortices, volume averaging, and osteoarthritis/enthesopathy can make detection of fracture lines and cortical step-off very difficult. In this situation, MRI is the best test for detection of fracture as well as for the associated soft tissue injury. MRI is also excellent for diagnosis of stress-related injuries, which may not be apparent radiographically. In its early stages, AVN of the femoral head is also not visualized on radiographs. MRI is highly sensitive and can guide rapid intervention such as core decompression. It is also the test of choice for infection because it can give an overall picture of soft tissue disease and spread as well as underlying osseous involvement. MR arthrography is the test of choice for detection of acetabular labral tear; an additional advantage of this invasive procedure is that although the needle is in the joint, anesthetic can be injected to give additional information regarding the site of pain generation.

AVASCULAR NECROSIS OF THE HIP (Figs. 11-1 through 11-6)

A number of predisposing conditions can result in AVN (the most common are listed in Box 11-1). Often, however, no cause is found (idiopathic is common). Patients present with groin pain, which becomes worse with weight-bearing.

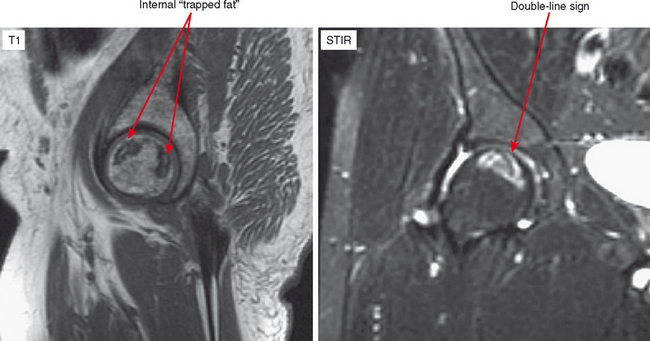

In the early stages of AVN, radiographs are negative. MRI will show diffuse marrow edema of the femoral head, possibly with some subchondral crescentic signal. At this stage, the differential diagnosis includes subchondral stress fracture or transient osteoporosis of the hip (TOPH). AVN does not show bone resorption because there is no blood flow. Therefore, to differentiate these entities the radiologist can perform a dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI looking for lack of enhancement (AVN) versus hyperemia (stress fracture, TOPH). Alternatively, noncontrast CT may show relative lucency of the femoral head in TOPH but not in the other conditions. However, care should be taken when comparing with the opposite side in patients who may have AVN bilaterally.

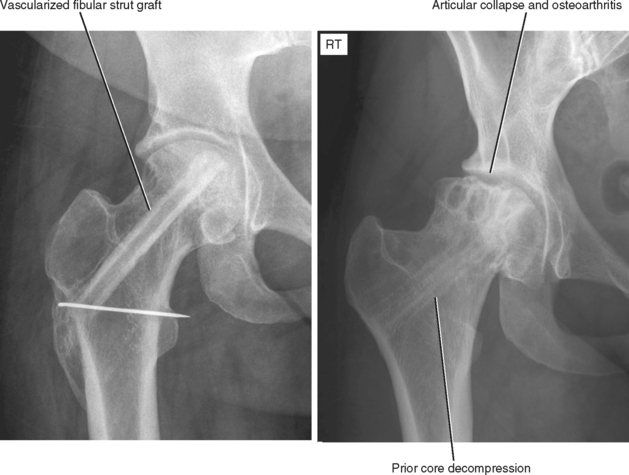

The Ficat staging system is a radiographic staging system, but it is still the most widely used. It has since been modified by the Subcommittee of Nomenclature of the International Association on Bone Circulation and Bone Necrosis; Table 11-1 summarizes the stages. The key is that appearance and progression are similar no matter what bone is affected. In other words, the disease progresses from radiographically occult to an increase in density, to collapse and fragmentation, to osteoarthritis. Treatment is based on the modified Ficat stage. However, in radiologic reports it always better to be descriptive rather than to list the stage because some surgeons may refer to the original Ficat staging, which is numbered differently.

Patients may go on for many years at the prior stage. When a patient with established AVN presents with acute pain, the suspicion and imaging should be directed toward finding articular collapse, which is often very subtle. On radiographs, a subchondral lucent line may be seen, representing a fracture. Flattening of the normally spherical femoral head indicates collapse. If no radiographic signs of collapse are seen, CT with sagittal and coronal reformats is very useful, especially when using multidetector CT with thin cuts. MRI can also be used, although CT has higher resolution. The advantage of MRI is visualization of the diffuse marrow edema that results from collapse, edema that extends to the intertrochanteric region simulating early AVN. If established AVN is seen in addition to this finding, certainly acute-on-chronic AVN is a possibility, but subtle articular surface collapse should be sought. Like AVN, the collapse is usually anterosuperior. TOPH is in the differential for diffuse femoral head edema, but underlying established AVN (or AVN on the other side) helps exclude this possibility.

TRANSIENT OSTEOPOROSIS OF THE HIP

Transient osteoporosis of the hip is a painful condition that was first described in patients in the third trimester of pregnancy (Figs. 11-7 through 11-9). Radiographs and CT show asymmetric osteopenia of the femoral head. MRI shows diffuse edema of the femoral head extending to the intertrochanteric region, an appearance that mimics early AVN. However, unlike AVN, TOPH resolves spontaneously. One theory is that TOPH is ischemia that does not go on to frank necrosis; another theory is that TOPH represents a subchondral stress fracture, much like spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee. Appearance in late pregnancy supports a stress-related etiology. Also supporting a stress origin is the presence of a subchondral crescentic low-signal region in many cases. CT (showing osteopenia) or dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (showing early contrast enhancement) should be able to differentiate TOPH from AVN.

STRESS FRACTURE (Figs. 11-10 through 11-13)

Stress fractures at the femoral neck tend to be solitary and unilateral. They tend to occur most frequently by far at the base of the medial femoral neck (the compressive aspect, where each step pushes the fracture sides together). Since bony apposition is essential for healing, stress fractures in this location have a good prognosis for healing. If the fracture occurs laterally, it is more unstable (this is the tensile aspect; weight-bearing tends to pull the fracture apart). The latter may be prophylactically treated with pin fixation.

TRAUMA

Occult Fracture (Figs. 11-14 through 11-17)

Hip and/or pelvic fractures may be undetectable (“occult”) on radiographs, even when they are reviewed after learning of the precise location. This situation is especially common in elderly patients who suffer a nondisplaced fracture through osteoporotic bone during a fall. Usually, a more severe injury is suspected clinically because the patient often cannot bear weight on the affected side, and additional imaging is requested. The best modality for definitive diagnosis of occult fracture is MRI. In fact, this exam is considered one of the few “musculoskeletal emergencies” (outside of spine imaging) that would prompt calling in the night technologist. During the day, an abbreviated hip survey exam (refer to protocols) can be performed in approximately 10 minutes, sandwiched between routine exams.

Nuclear medicine bone scan is too insensitive in the acute phase of occult fracture. A traditional low-cost alternative to advanced imaging, that being conservative therapy with follow-up radiographs, is not an option in this setting because the fracture can displace and become more complicated in addition to pulmonary embolism and other dreaded complications resulting from prolonged immobilization of the elderly.