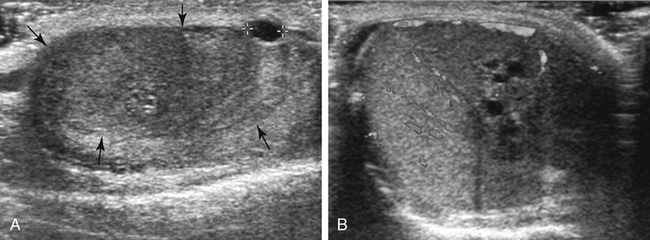

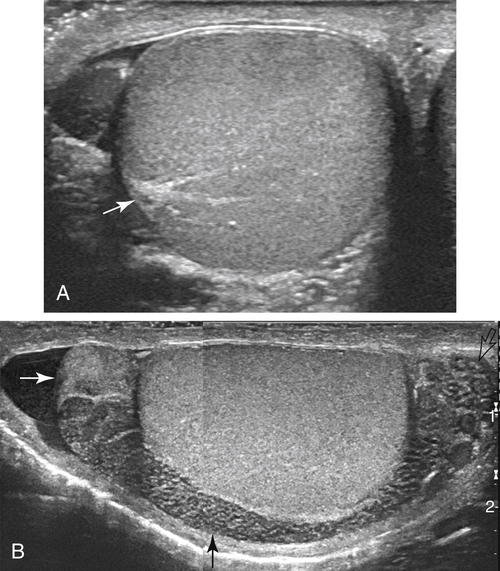

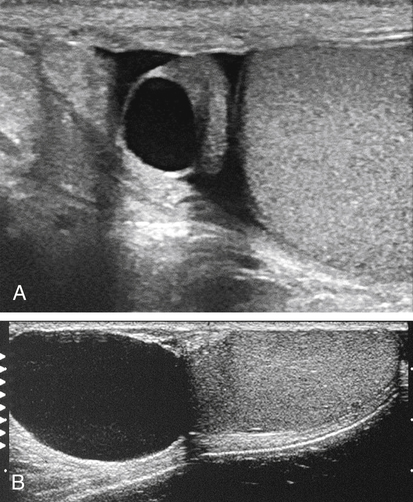

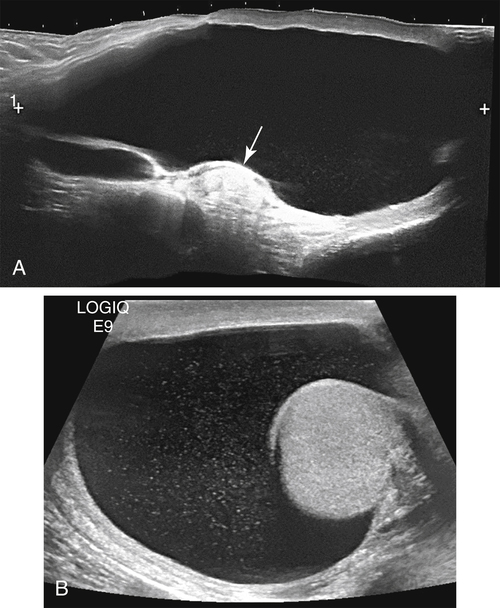

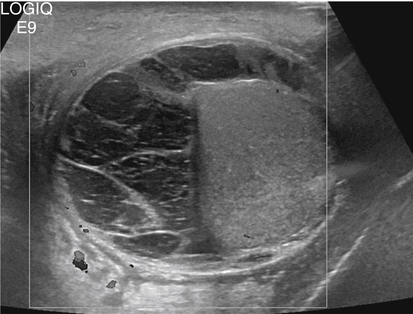

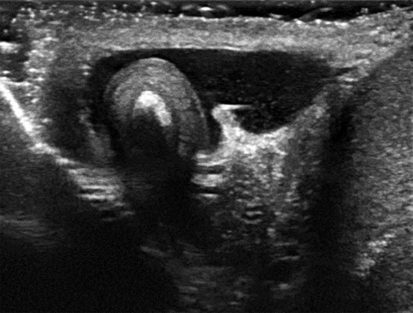

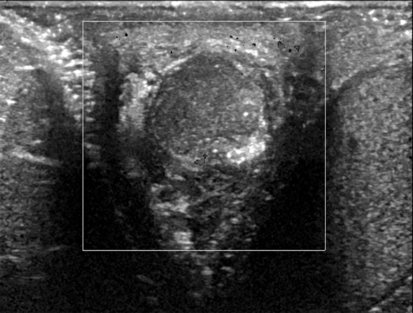

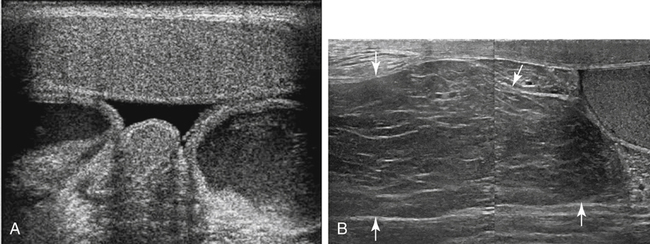

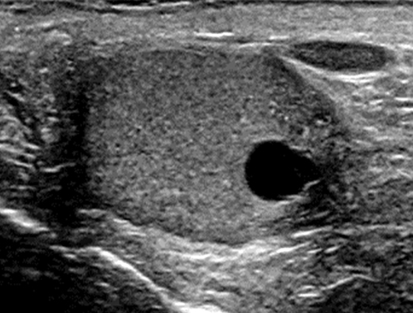

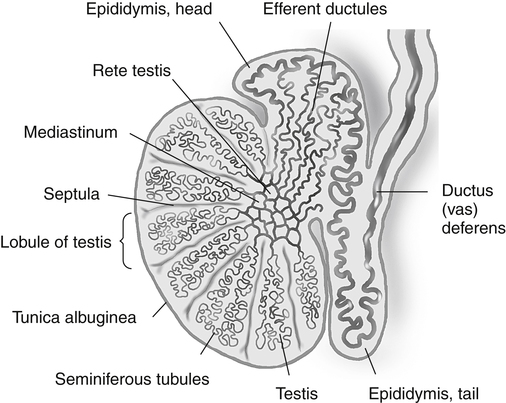

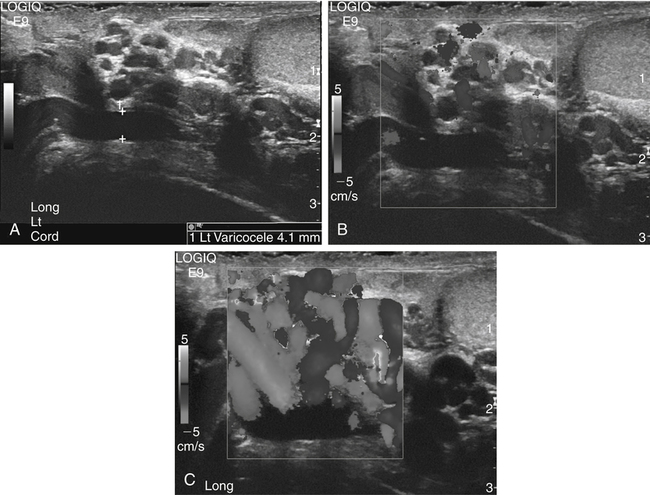

• Describe the sonographic appearance of the normal scrotal contents. • Identify the clinical signs and symptoms of benign processes in the scrotum. • Describe the sonographic appearance of benign findings in the scrotum. • Identify the clinical signs and symptoms of clinically significant processes in the scrotum. • Describe the sonographic appearance of common clinically significant pathologies of the scrotum. The scrotum is an outpouching of the lower abdominal wall, with layers derived from the muscles and connective tissues. The structures contained within the scrotum are the testicles, the epididymides, and the proximal spermatic cords (Fig. 28-2). The testicles are two ovoid spermatogenic endocrine glands separated from each other within the scrotum by the scrotal septum. Each testicle has a capsule of fibrous connective tissue called the tunica albuginea. At the posterior aspect of the testicle, the tissue of the tunica albuginea enters the testicle to form the mediastinum testis and then extends toward the outer capsule as numerous septa, which create lobules that house the spermatogenic seminiferous tubules. The seminiferous tubules converge at the mediastinum to form the rete testis, a network of microtubules, which gives off several efferent ductules. The epididymal head comprises the convoluted efferent ductules that transport spermatozoa out of the testis into the epididymis. The ductules of the head converge to become a single coiled duct, the epididymal body and tail, passing next to the testis from the upper pole toward the lower pole. Near or at the inferior pole of the testis, the duct turns back toward the upper pole, deconvolutes, and enlarges slightly to become the ductus deferens, which exits the scrotum as part of the spermatic cord. Each scrotal compartment, or hemiscrotum, is lined by tunica vaginalis, a serous membrane that also covers the testicle and epididymis and encloses the potential peritesticular space. Normal testicles are homogeneous and mildly echogenic except for the mediastinum testis, which is hyperechoic, is of variable thickness, and runs along the posterolateral side of the testicle in a craniocaudal orientation (Fig. 28-3, A). Each testicle is approximately 5 cm × 3 cm × 2 cm in size. The peritesticular spaces normally contain small amounts of serous fluid. The normal epididymis may have a perceptible tubular appearance and has an echogenicity that is less than the testicle, although the head may be more echogenic than the rest of the epididymis (Fig. 28-3, B). Epididymal cysts and spermatoceles are indistinguishable sonographically. Both may appear as anechoic simple cysts (Fig. 28-4) or may contain fine low-level echoes, sometimes with precipitative layering. Scrotal cysts can be several centimeters in diameter and can be mistaken for a large hydrocele. Neither epididymal cyst nor spermatocele is of clinical significance unless large enough to be symptomatic. Spermatoceles tend to be solitary, whereas epididymal cysts are often multiple. A hydrocele appears as a fluid collection next to or around the testis, sometimes with septations. It might be seen as a relatively small amount of free paratesticular fluid, or it might be massive, enlarging the hemiscrotum greatly and compressing the testis against the inner scrotal wall. Large hydroceles are better demonstrated with dual imaging or an extended field of view (Fig. 28-5). In chronic hydroceles, echoes may be seen within the fluid; documenting acoustic streaming within such a hydrocele confirms the diagnosis. A very large hydrocele can be confused with a massive extratesticular cyst. Varicoceles appear as dilated fluid-filled tubular structures in the posterolateral aspect of the scrotum measuring greater than 2 mm.1 Echogenic blood may be seen moving slowly through the veins, but color Doppler is essential in the diagnosis of a varicocele (Fig. 28-6; see Color Plate 38). Increased flow is identified within the prominent veins when the patient performs the Valsalva maneuver and is scanned while the patient is standing. Measuring the vein diameter should be done during the Valsalva maneuver also. If a large or unilateral right-sided varicocele is discovered, the right upper and lower quadrants should be investigated for external compression of the right testicular vein. A pyocele appears as a complex, sometimes septate fluid collection surrounding the testis (Fig. 28-7; see Color Plate 39). Unusual presentations include relatively homogeneous and echogenic material around the testis or a discrete mass near the testis. Gentle transducer pressure sometimes creates visible movement of the pyocele echoes. Similar to other peritesticular fluid collections, they can be of any size but rarely achieve several centimeters in greatest dimension. Scrotal pearls are highly echogenic and sometimes have a less echogenic fibrous “rind” or concentric rings of varying echogenicity (Fig. 28-8). They are more likely to be seen in the presence of a hydrocele and may not be noticeably mobile. Although calcified, they may not shadow. Sonography reveals a mass of greatly variable echogenicity and echotexture depending on what structures are herniated to the scrotum (Fig. 28-10). There may be variably echogenic fluid with or without a visible hernia sac or a solid mass of varying complexity. Shadowing from air may be identified. If peristaltic motion is identified, the diagnosis of scrotal hernia is confirmed. Gentle transducer pressure may demonstrate reduction of a hernia in the proximal scrotal space, and a Valsalva maneuver may force a hernia deeper into the hemiscrotum; both can aid in the diagnosis. Sonography is not dependable for differentiating indirect from direct hernias. Tunica albuginea cysts form in the tunica albuginea and are typically present in men 30 to 50 years old. They range in size from 2 mm to 3 cm, but most are less than 1 cm in diameter.1 They are painless and palpable at the testicular surface as a classic “BB” or “pea” presentation. Epidermoid cysts account for only about 1% of testicular neoplasms. They are benign keratin-containing cysts with an “onion-skin” lamellar architecture. They most commonly are discovered as a well-circumscribed, painless testicular mass in postpubertal boys and men 40 years old or younger.1 Epidermoid cysts manifest as well-defined hypoechoic round or oval masses, and although they are cysts, acoustic enhancement is absent (Fig. 28-12). The concentric laminar architecture within these lesions sometimes generates a whorled appearance that is suggestive of the diagnosis. Also suggestive is the absence of internal vascularity on Doppler examination. If these characteristics are seen in a testicular mass, it must be reported so that surgical planning can allow for the possibility of a testis-sparing enucleation.

Scrotal Mass and Scrotal Pain

Scrotum

Sonographic Findings

Extratesticular Mass

Cysts and Fluid

Epididymal Cysts and Spermatoceles

Sonographic Findings

Hydrocele

Sonographic Findings

Varicocele

Sonographic Findings

Pyocele

Sonographic Findings

Solid Lesions

Scrotal Pearls

Sonographic Findings

Scrotal Hernia

Sonographic Findings

Cystic Testicular Mass

Tunica Albuginea Cyst

Epidermoid Cyst

Sonographic Findings

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Scrotal Mass and Scrotal Pain