Upper Gastrointestinal Obstruction

Teresa Chapman, MD

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

1. Recognize clinical and radiographic features concerning for upper GI tract obstruction.

2. List an appropriate differential diagnosis for the double bubble sign on prenatal imaging.

3. Describe the ductal anatomy of annular pancreas and the significance of its diagnosis in children.

4. Diagnose malrotation by upper GI series and describe expected sonographic features.

5. Indicate significance of clockwise versus counterclockwise rotation of superior mesenteric artery and vein on imaging.

6. Recognize expected anatomy on imaging following a Ladd procedure.

7. List sonographic criteria for the diagnosis of hypertrophic pyloric stenosis.

INTRODUCTION

Obstruction of the upper gastrointestinal tract may be due to congenital or acquired abnormalities and may present with abdominal distention or vomiting. In the newborn, in particular, recurrent emesis is attributable to gastroesophageal reflux in approximately 30% of cases.1 However, bilious emesis, referring to the yellow or green discoloration of the gastric contents by bile, is concerning for an obstruction in the upper GI tract that would merit emergent surgery and should be treated as an indication for surgery until proven otherwise.2 Projectile vomiting is another feature that raises concern for gastric outlet obstruction. Diagnostic imaging plays an important role in differentiating etiologies of obstruction that may or may not require urgent surgical intervention. In this chapter, obstructive lesions of the gastric outlet and of the proximal small bowel will be discussed, with a description of the relevant clinical factors, appropriate imaging, and treatment.

NEONATAL UPPER GI TRACT OBSTRUCTION

Normally, a healthy newborn infant will begin swallowing air and consuming milk very soon after birth. Gradually, the gastrointestinal tract will fill with air, and an abdominal radiograph will show gas in nondilated loops of bowel all the way through the rectum by 24 hours of life (Fig. 12.1). A congenital obstruction of the upper GI tract may either partially or fully obstruct the forward peristalsis of intraluminal contents, and the infant will present with emesis. The radiographic findings, then, may include distention of the tract upstream from the obstructive lesion and a paucity or absence of gas distal to it.

DUODENAL ATRESIA AND STENOSIS

Small intestinal atresia is congenital absence of a portion of bowel, or congenital narrowing of the duodenum, jejunum, or ileum, leading to complete luminal obstruction.3 The incidence of duodenal atresia is 1.80 in 10,000 live births,4 and there is a strong association of this malformation with chromosomal anomalies, particularly trisomy 21. Other concomitant disorders include cardiac anomalies, malrotation, and VACTERL-associated anomalies.4,5 Approximately 30% of cases of duodenal atresia are diagnosed in infants with trisomy 21.4,6 Duodenal atresia may be diagnosed prenatally, based on identification of polyhydramnios and the “double bubble” sign, which refers to the distention of both the stomach and the proximal duodenum.7 It is important to keep in mind that approximately 40% of prenatally detected duodenal atresia cases are isolated anomalies.8

Postnatal assessment of the infant may not require further imaging, if the prenatal imaging and genetic evaluation are strongly suggestive of duodenal atresia. In the unsuspected case of small bowel atresia, however, abdominal radiography may be performed initially to assess the bowel gas pattern. The atretic segment of the duodenum will completely obstruct gas beyond the proximal duodenum (Fig. 12.2). In the setting of duodenal stenosis, findings will not necessarily show an obvious obstruction, and nonspecific gastric distention and a small amount of bowel gas are the most commonly seen findings (Fig. 12.3). If the clinical assessment and radiographic examination is strongly suggestive of the diagnosis, surgical correction with resection of the atretic segment and creation of an oblique anastomosis (duodenoduodenostomy) will be pursued either by open or laparoscopic technique, with good published outcomes.9, 10 and 11 Balloon dilatation of membranous duodenal stenosis has also been described.12 Upper gastrointestinal tract fluoroscopy with enteric contrast may still be necessary in some cases, and the diagnosis would be confirmed by failure of enteric contrast to pass beyond the atretic segment (Fig. 12.4), or a trace amount of contrast to pass through a stenotic segment, with dilatation of the upper GI tract proximal to the obstruction.

FIG. 12.3 • Duodenal stenosis on abdominal radiography. Neonate with surgically confirmed duodenal stenosis shows similar findings as the newborn with duodenal atresia in Figure 12.2, except that bowel gas is present in more distal loops of bowel. (St, stomach; DB, duodenal bulb.) |

The clinical and radiographic presentations of duodenal atresia are not specific, and the differential diagnosis includes intraluminal duodenal diverticulum (duodenal web), congenital abnormalities causing extrinsic compression upon the descending duodenum, and acquired extrinsic compression by duodenal hematoma (discussed in Chapter 18). In one study of 40 newborns presenting with duodenal obstruction,11 the surgical diagnoses were as follows: 4 duodenal atresia, 8 duodenal stenosis, 8 annular pancreas, and 20 intestinal malrotation.

DUODENAL WEB

Duodenal web and intraluminal duodenal diverticulum (IDD), or “windsock” diverticulum, are rare congenital anomalies resulting from incomplete recanalization of the foregut early in embryologic development. A nonobstructive persistent web or diaphragm of tissue may gradually stretch over time with peristalsis, forming an intraluminal diverticulum.13 The IDD is lined by duodenal epithelium on both surfaces, and the size of the opening in the center of the membrane will determine the degree of obstruction and timing of presentation—individuals who remain asymptomatic until adulthood have a larger communication between the lumen of the diverticulum and the lumen of the more distal duodenum.14 The presence of a diverticulum may be

recognized on various modalities of diagnostic imaging, including upper gastrointestinal series, abdominal CT, and abdominal MR imaging.15 The diagnostic features on upper GI series include a contrast-filled collection or filling defect that assumes the shape of a windsock and may change in position with peristalsis (Fig. 12.5). Intraluminal webs can be treated endoscopically by snaring and resecting the abnormal tissue.14

recognized on various modalities of diagnostic imaging, including upper gastrointestinal series, abdominal CT, and abdominal MR imaging.15 The diagnostic features on upper GI series include a contrast-filled collection or filling defect that assumes the shape of a windsock and may change in position with peristalsis (Fig. 12.5). Intraluminal webs can be treated endoscopically by snaring and resecting the abnormal tissue.14

ANNULAR PANCREAS

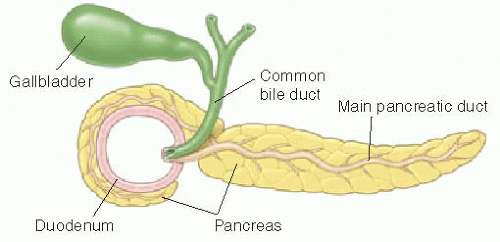

The characteristic feature of annular pancreas is a partial or complete ring of pancreatic tissue encircling the descending duodenum and potentially causing obstruction. There are various theories about the embryologic development of this anomaly, but most agree that the tissue originates from abnormal migration of the ventral pancreatic bud.16 The annular pancreas is histologically identical to normal pancreas, and the ring of tissue may contain a major pancreatic duct that wraps posteriorly around the duodenum and enters the duct of Wirsung near the ampulla of Vater (see schematic Fig. 12.6).16

This anomaly has a reported incidence of approximately 1 in 1,000.17 Because the amount of pancreatic tissue surrounding the second portion of the duodenum varies and may not cause obstruction, there are some cases that do not present until adulthood or that are identified at autopsy.18 However, the differences between children and adults with this anomaly differ substantially more than simply in the degree of duodenal obstruction.17 Of note, approximately 70% of pediatric patients with this anomaly have concomitant anomalies—most commonly trisomy 21, cardiac malformations, and intestinal anomalies.16,17

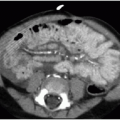

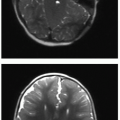

Diagnosis may be suspected on upper GI series when there is narrowing of the descending duodenum by extrinsic compression, which would be suggested based on obtuse margins along the area of narrowing and otherwise normal appearance of the mucosa (Fig. 12.7). Dilatation of the more proximal duodenum may or may not be present. The diagnosis may be incidental on cross-sectional imaging, with tissue isodense or isointense to normal pancreatic gland wrapping around the descending duodenum (Fig. 12.8). MR cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) exploits the fluid signal in the hepatobiliary ducts and pancreatic duct to delineate the ductal anatomy and may be helpful in this diagnosis.19 Recognition of this entity by ultrasound has also been described in infants,18 enabled by the abnormal continuation of the pancreatic duct anterior to the duodenum. Symptomatic cases require surgical duodenal bypass, usually by duodenoduodenostomy and occasionally duodenojejunostomy.17

MALROTATION WITH MIDGUT VOLVULUS

Malrotation is a congenital anomaly referring to abnormal rotation and fixation of the bowel within the abdominal cavity.20, 21, 22 and 23 Early in normal embryonic development, the right colon is present in the left aspect of the abdomen, the duodenum and jejunum are to the right of the mesenteric vessels, and a portion of the midgut physiologically herniates outside of the coelomic cavity into the umbilical cord.22 A normal 270-degree counterclockwise rotation of the bowel occurs around the axis of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) before the return of the bowel to the abdominal cavity (see schematic Fig. 12.9). Subsequently, the mesocolon fuses to the posterior abdomen, and the mesentery is anchored from the ligament of Treitz downward obliquely to the cecum. If this sequence of events does not occur, the intestine is malrotated. There are three important features to be aware of with this abnormality: (1) The resulting anatomy can span a spectrum from nonrotation (the large bowel is entirely in the left abdomen and the small bowel is entirely in the right abdomen) to the opposite extreme of omphalocele in the newborn; (2) the abnormal fixation of the mesentery results in the individual being susceptible to midgut volvulus, wherein the intestines abnormally twist around the vasculature of the mesentery, resulting in bowel ischemia, a potentially fatal consequence if not immediately treated surgically; and, (3) Ladd bands may be present, causing extrinsic compression of the duodenum, even in the absence of midgut volvulus.21,23