Vascular |

See Table 18.2 Mediastinal vascular disease |

Inflammatory |

Pancreatic pseudocyst

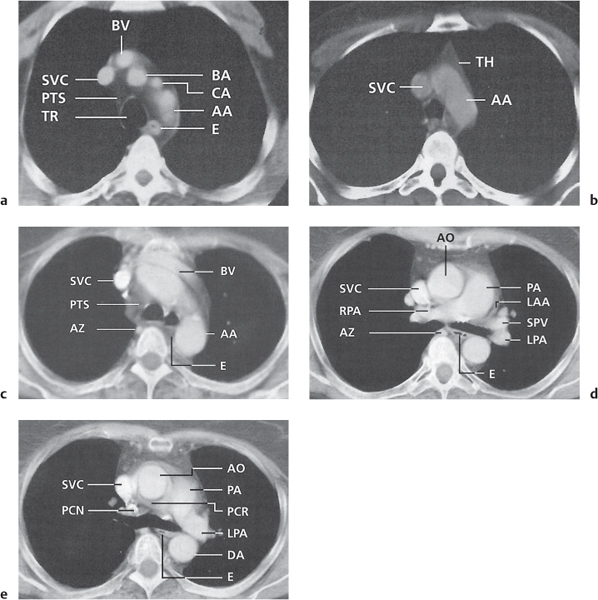

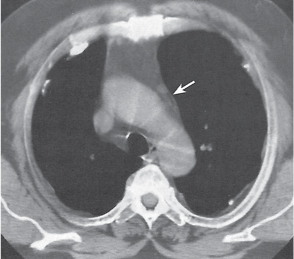

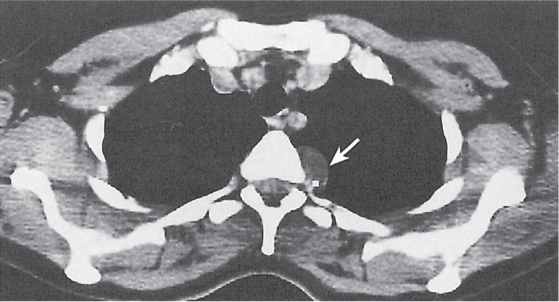

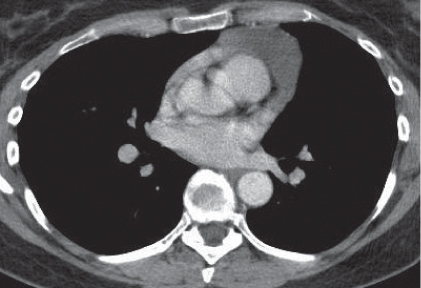

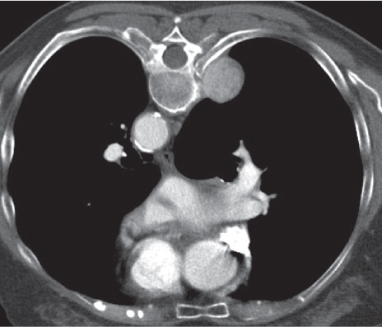

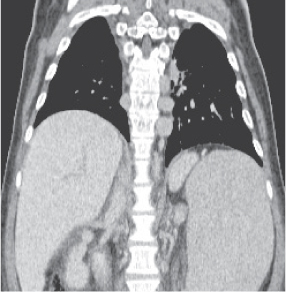

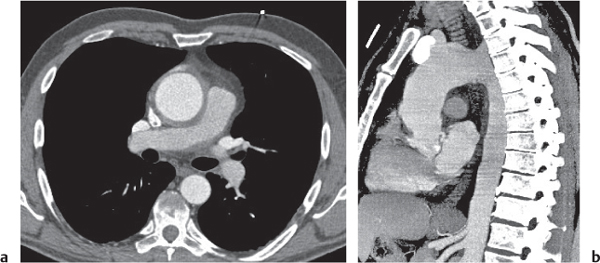

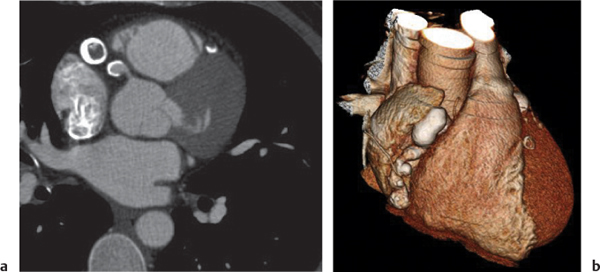

Fig. 18.4 |

Fibrous encapsulated fluid collection of inflammatory pancreatic exudate.

Diagnostic pearls: On precontrast scans, well-defined hypodense mediastinal cystic lesion is seen. Cyst walls may calcify. Low-density intracystic gas bubbles are seen in cases of secondary infection. |

Evidence of pancreatitis may be present on abdominal CT in a patient with signs of chronic pancreatitis or following pancreas surgery/interventions.

Usually extends through the esophageal hiatus from the abdomen. |

Nonspecific lymph node hyperplasia

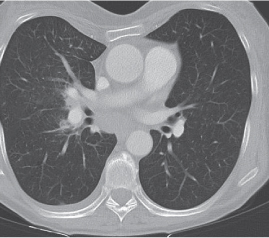

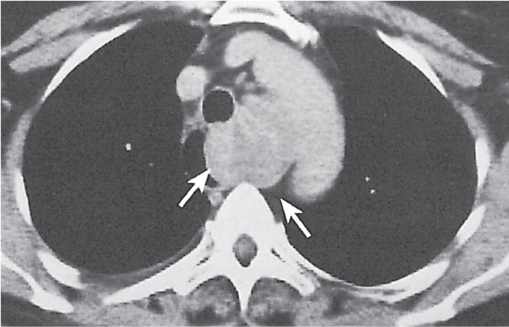

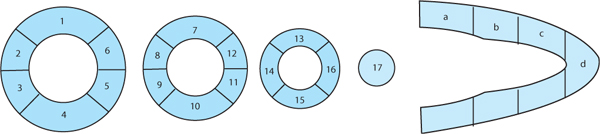

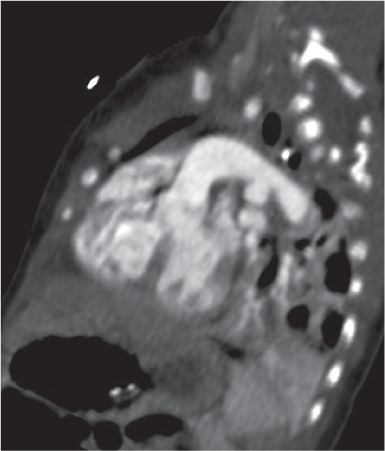

Fig. 18.5 |

Lymph node hyperplasia in association with a variety of pulmonary or generalized infections.

Diagnostic pearls: Slightly enlarged, sharply marginated lymph nodes with homogeneous contrast attenuation. |

CT appearance of hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes lacks specific morphologic appearance to serve diagnostic purposes. |

Sarcoidosis

Fig. 18.6 |

Symmetric mediastinal and hilar lympadenopathy in patients with suspected sarcoidosis.

Diagnostic pearls: Enlargement of the paratracheal and preaortic lymph nodes in the upper mediastinum and symmetrical hilar lymphadenopathy are characteristic. Large conglomerates may occur. Calcifications are rare and occur late.

Lympadenopathy may occur with or without micronodular lung opacities, involving preferentially the middle and upper portions of the lung. |

Histologically, well-defined granulomas with a rim consisting of fibroblasts and lymphocytes.

In the absence of characteristic pulmonary parenchymal changes, malignant lymphoma is an important differential diagnosis. |

Pneumoconiosis |

Inflammatory lung disease caused by a variety of organic and chemical antigens.

Diagnostic pearls: Lung manifestations often with associated minor enlargement of hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes. In patients with chronic exposition setting, lymph nodes show centripetal ringlike calcifications. |

Lymph node changes are nonspecific, but pulmonary parenchymal findings are usually diagnostic. |

Chronic granulomatous or sclerosing mediastinitis |

Separate ends of a spectrum of chronic granulomatous inflammation of the mediastinum.

Diagnostic pearls: Lobulated, elongated soft tissue mass may be detected in any part of the mediastinum. Commonly contains calcification and is predominantly right-sided. |

Caused by a long-standing inflammation of the mediastinum leading to growth of acellular collagen and fibrous tissue within the chest and around the central vessels and airways. Major airway or superior vena cava compression may be present.

May be associated with tuberculosis (TB), sarcoidosis, or a manifestation of idiopathic fibrosclerosis.

Has a different cause, treatment, and prognosis than acute infectious mediastinitis. |

Megaesophagus

Fig. 18.7

Fig. 18.8 |

Characterized by > 10 cm luminal widening of the esophagus.

Diagnostic pearls: Often contains fluid or air–fluid level. Wall thickness > 3 mm when distended. |

Underlying cause of megaesophagus is chronic or recurrent inflammation, such as achalasia, Chagas disease, scleroderma, and candidiasis in immunocompromised patients. |

Tracheomalacia

Fig. 18.9

Fig. 18.10 |

Flaccidity of the tracheal support cartilage leading to focal tracheal collapse and concomitant cranial widening, especially when increased airflow is demanded.

Diagnostic pearls: Focal narrowing of the medial and distal trachea with dilation cranially to it; sometimes thickened walls within dilated tracheal segment. |

Tracheomalacia has a variety of etiologies, including polychondritis, complication of tracheal intubation, tumors, foreign bodies, and congenital tracheal stenosis.

Physiologically, the trachea slightly dilates during inspiration and narrows during expiration.

These processes are exaggerated in tracheomalacia, leading to airway collapse on expiration. The usual symptom of tracheomalacia is expiratory stridor or laryngeal crow. |

Congenital |

Bronchogenic cyst

Fig. 18.11 |

A usually spherical cyst arising as an embryonic outpouching of the foregut or trachea.

Diagnostic pearls: Round or oval, well-defined, very thin-walled, nonenhancing near-water-density mass. Characteristic location is just below the carina, protruding toward the right. Contour may be affected by contact with more solid structures. Rarely calcifies. |

Also referred to as bronchial cyst and usually asymptomatic unless it becomes infected.

Seen in different age groups from infants through adults. Can potentially be life-threatening, as cysts can lead to compression, hemorrhage, rupture, or infection.

Most common in the middle mediastinum; may occur in the posterior and occasionally in the anterior mediastinum. May contain viscous material and have a density up to 60 HU but usually does not enhance. |

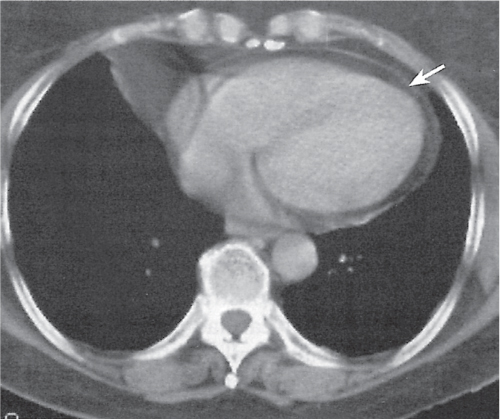

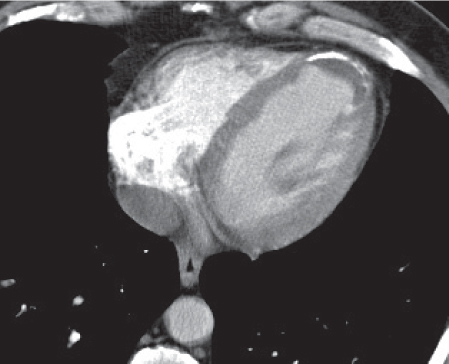

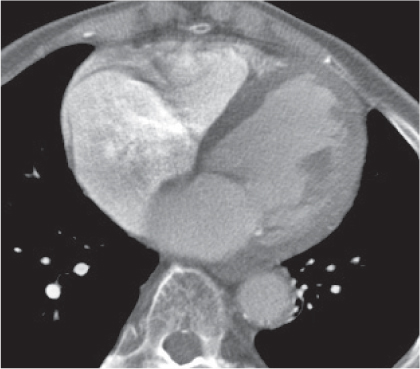

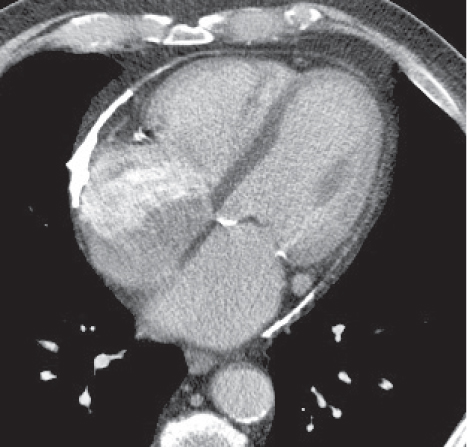

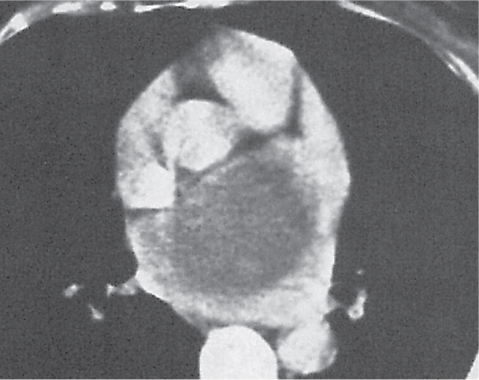

Pericardial cyst

Fig. 18.12 |

Usually asymptomatic, rare benign congenital anomaly in the middle mediastinum.

Diagnostic pearls: Round, smooth, thin-walled, nonenhancing mass of near-water density, most commonly located in the right cardiophrenic angle (middle or anterior mediastinum). May change shape when the patient is turned from supine to prone position.

Near-water attenuation differentiates pericardial cysts from lipomas and fat pads. |

Incidence rate: 1/100,000. Occurs most frequently in the third or fourth decade of life and equally among men and women.

Pericardial cysts represent 6% of mediastinal masses, 33% of mediastinal cysts. Other cysts in the mediastinum are bronchogenic (34%), enteric (12%), thymic and others (21%). In the middle mediastinum, 61% of presenting masses are cysts. Pericardial and bronchogenic cysts share the second most common etiology after lymphomas. |

Neurenteric cyst, gastroenteric cyst

Fig. 18.13 |

A combination of an endodermal cyst with a vertebral dysplasia.

Diagnostic pearls: Smooth, thin-walled, nonenhancing mass of near-water density in the posterior mediastinum. May contain viscous material and have a density near soft tissue but does not enhance. |

Neurenteric cysts, along with Rathke cleft and colloid cysts, are endodermally derived lesions of the central nervous system (CNS). Spine anomalies may be associated. |

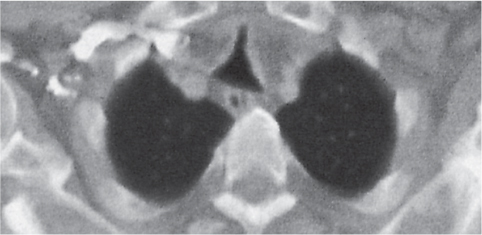

Thoracic meningocele

Fig. 18.14 |

A closing disorder of the neural tube with herniation of the meninges through a vertebral column defect.

Diagnostic pearls: Well-defined, solitary or multiple, water-density paravertebral posterior mediastinal lesion. May appear bilateral. No enhancement after intravenous (IV) contrast administration. Enhances only after intrathecal contrast administration. |

Most meningoceles occur in the lower lumbar region and manifest after birth. Occult meningoceles manifest later. Widening of the spinal canal and vertebral erosion is often associated. |

Lymphangioma |

Congenital malformation of lymphatic channels.

Diagnostic pearls: Anterosuperior mediastinal mass usually adjunctive with a larger component in the neck; multiloculated, homogeneous, smooth mass near-water density; often appears cystic. May compress nearby structures. Usually no attenuation on postcontrast scans. |

Histologically, lymphatic sacs lined with endothelial cells, cavernous or cystic. Three to 10% of all cervical lymphangiomas extend into the mediastinum.

Classified into three subtypes: simple, cavernous, or cystic. May be asymptomatic in middle-aged persons. More common in male children/infants.

Cystic hygroma occurs in children and may be clinically apparent at birth or within 2 y. |

Bochdalek herniation |

Herniation through the lumbocostal triangle.

Diagnostic pearls: A low left-sided, rarely bilateral, posterior mediastinal mass is seen at a paravertebral location; enters into the chest between the chest wall and the spleen (see also Fig. 17.20).

May contain fat only, or rarely also bowel loops. |

The most common congenital defect of the diaphragm. Bochdalek foramen is a lumbocostal triangle located posterolaterally. A hernia occurs in the presence of an incomplete closure of the pericardioperitoneal canals by the pleuroperitoneal membrane. A large Bochdalek hernia may be a rare cause of acute respiratory distress in neonates. |

Traumatic |

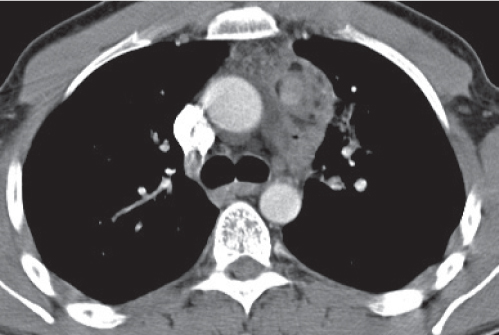

Pneumomediastinum

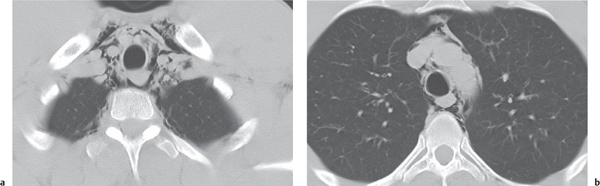

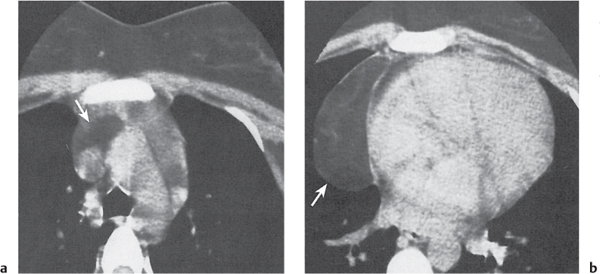

Fig. 18.15a, b |

Extraluminal/pulmonary air within the mediastinum.

Diagnostic pearls: Mediastinal streaks or bubbles of air, often extending from/to the neck. May be associated with subcutaneous or pulmonary interstitial emphysema and/or pneumothorax. |

More often spontaneous than traumatic. |

Fracture of vertebra with hematoma |

Paravertebral soft tissue mass associated with vertebral fracture (s).

Diagnostic pearls: Similar findings as in mediastinal hemorrhage or hematoma but usually confined to the posterior mediastinum. |

Typically high-speed car accidents or falls. |

Infectious |

Tuberculosis (TB) |

Lymph node enlargement due to an infection with mycobacteria tuberculosis.

Diagnostic pearls: Asymmetrically enlarged paratracheal and tracheobronchial lymph nodes in the acute phase. On postcontrast scans, lymph nodes often show peripheral enhancement and central areas of necrosis-related hypodensity. In subacute/chronic TB, lymph nodes may conglomerate and show speckled calcifications. |

Characteristic pulmonary parenchymal changes are typically present (see also Fig. 16.39). |

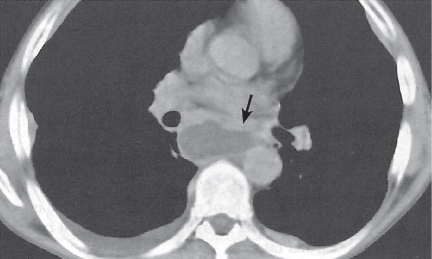

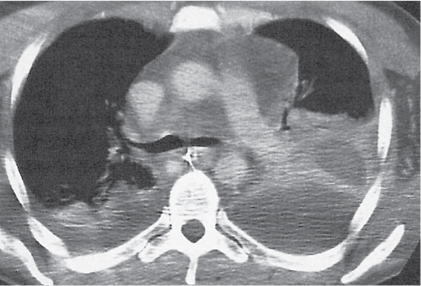

Acute mediastinitis, mediastinal abscess

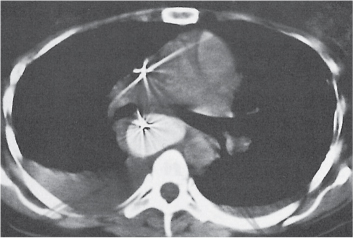

Fig. 18.16 |

Acute mediastinitis is usually caused by bacterial overgrowth following a rupture of either the trachea or esophagus. It may progress rapidly into a mediastinal abscess.

Diagnostic pearls: Hypoattenuating diffuse, mediastinal widening associated with small gas bubbles. Discrete cavity with a shaggy, slightly enhancing wall represents an abscess. |

Esophageal rupture is the most common cause and is associated with larger amounts of mediastinal gas. Any infection in the neck may also spread into the mediastinum.

After sternotomy, gas bubbles and fluid in the anterior mediastinum are indicative of an infection. |

Acute anthrax |

Acute infection caused by Bacillus anthracis.

Diagnostic pearls: Symmetric widening of the anterior and middle mediastinum resulting from hemorrhagic, diffuse edema of lymph nodes. Patchy pulmonary opacities and pleural effusion are also seen. |

B. anthracis is a rod-shaped, gram-positive aerobic bacterium that is about 1 × 9 μm in length. There are 89 known strains of the bacteria. They produce two powerful exotoxins and a lethal toxin. Most common among sorters and combers in the wool industry. Pulmonary changes are more prominent than mediastinal ones. |

Spondylitis |

Either an inflammation or infection of the vertebrae depending on the underlying cause.

Diagnostic pearls: Fusiform, ill-defined, low-density paravertebral mass. Erosion or destruction of vertebral bodies at the level of the mass; usually in the inferior thoracic spine.

Distinct attenuation on postcontrast scans. |

Pyogenic spondylitis usually affects one disk space only. Involvement of multiple disk spaces and large calcified paraspinal masses suggest spinal tuberculosis (Pott disease), marked by stiffness of the vertebral column, pain on motion, tenderness on pressure, prominence of certain vertebral spines, and occasionally abdominal pain, abscess formation, and paralysis.

Ankylosing spondylitis is a human leukocyte antigen (HLA) B27–associated autoimmune inflammation involving the spine and sacroiliac joints. |

Neoplastic/thymic tumors |

Thymic hyperplasia, thymic rebound hyperplasia

Fig. 18.17 |

Diffuse symmetric enlargement of the thymic gland.

Diagnostic pearls: Particularly the anteroposterior thickness of the gland is increased with preservation of the normal shape. Attenuation remains unchanged. Differentiation from thymic carcinoma usually not possible. |

In adults, normal thymus measures < 1.3 cm. Thymic hyperplasia (i.e., thymoma) may be associated with hyperthyroidism as in Graves disease, acromegaly, Addison disease, and myasthenia gravis. Rebound hyperplasia occurs in children and young adults recovering from severe illness, after treatment for Cushing disease, or chemotherapy. Rebound may simulate recurrence of neoplasm on CT but is actually a transient overgrowth that resolves with time or after steroid treatment. |

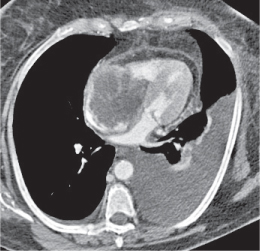

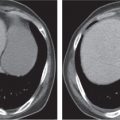

Lipoma, thymolipoma

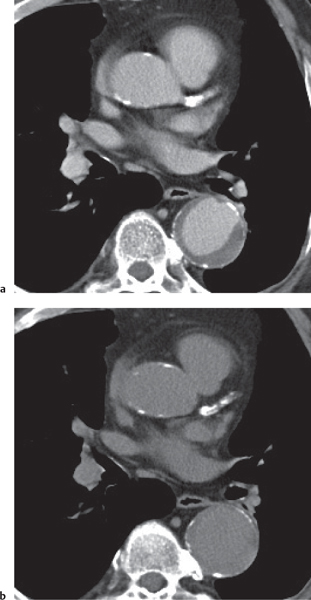

Fig. 18.18a, b |

Rare benign mediastinal masses.

Diagnostic pearls: Large, smooth, or lobulated fat-density mass within the anterior mediastinum. Usually indistinguishable from lipomas, but may contain components of soft tissue density. |

Asymptomatic benign mass predominantly composed of fat (50%–80%). Lipoma may also occur in other parts of the mediastinum.

Thymolipoma is found only in the anterior mediastinum. Liposarcoma of the mediastinum is extremely rare, generally has a higher postcontrast attenuation than fat, and is more commonly found in the posterior mediastinum. |

Thymic cyst

Fig. 18.19 |

Solitary or multiloculated, water-density, thin-walled anterior mediastinum lesion.

Diagnostic pearls: Near-water density attenuation of the cyst. Size ranges from some mm to > 12 cm. Usually no mural enhancement. Thin intracystic septations, hemorrhage and (subsequent), calcifications are observed. |

Constitutes 1% of all mediastinal masses. Usually congenital, but may also be inflammatory or neoplastic.

Often found in patients with Hodgkin disease either concomitantly or following radiation therapy. It may persist after therapy and thus usually does not reflect a residue or recurrent lymphoma. |

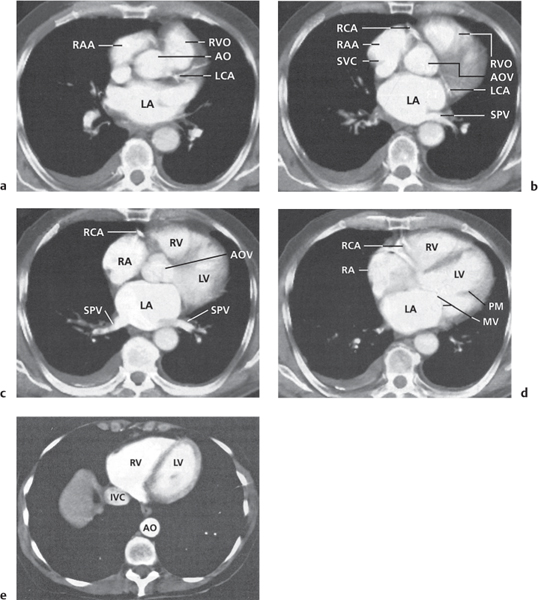

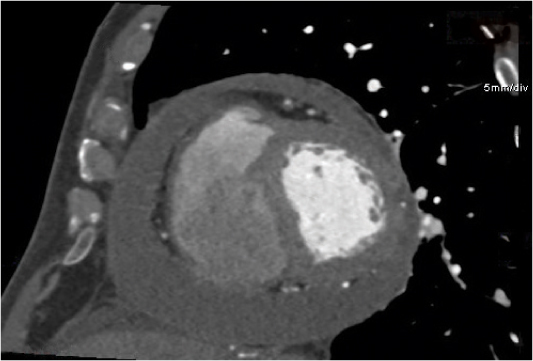

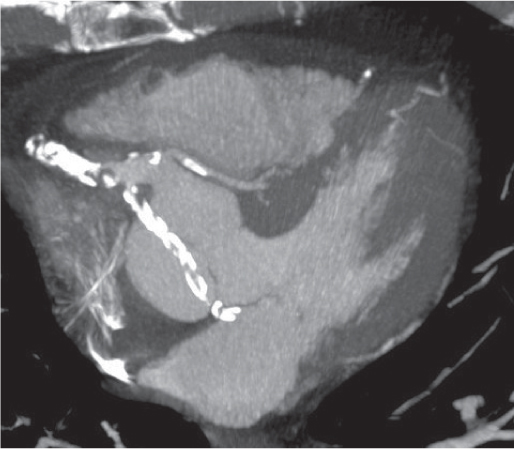

Thymoma

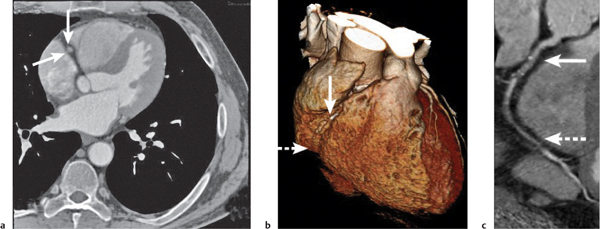

Fig. 18.20 |

Epithelial thymic neoplasm in the anterior mediastinum.

Diagnostic pearls: Round, oval, or lobulated well-defined mass of thymic density without a visible capsule; 25% show focal calcifications. Contrast uptake may be homogeneous in small lesions and heterogeneous in larger lesions. Convex shape and lobulation favor thymoma over thymic rebound or persistent thymic tissue.

Invasive thymoma (35%) has a muscle-equivalent density and shows a mild enhancement, but can also be heterogeneous and have eggshell calcifications. Pleural or pericardial deposits are indicative of malignancy. |

Shows a variable amount of lymphocytes. The most common primary mediastinal tumor (20%) usually seen in adults.

Predominantly in patients 50 to 70 y of age; no gender preponderance.

Fifty percent of patients are asymptomatic, 30% present with myasthenia gravis, 20% with symptoms due to mediastinal infiltration or compression.

Ten to 15% of patients with myasthenia gravis and hypogammaglobulinemia also have a thymoma. Thymic carcinoid is not distinguishable from thymoma. Thymic carcinoma is a poorly defined large anterior mediastinal mass that commonly invades adjacent structures. Thymic Hodgkin lymphoma may be difficult to distinguish from thymoma even histologically. Chest wall invasion and lymphadenopathy suggest lymphoma (nodular sclerosis). |

Neoplastic/germ cell tumors (GCTs) |

Teratoma

Fig. 18.21 |

The vast majority (70%) of benign to low-malignant mediastinal GCTs.

Diagnostic pearls: Mature and immature teratomas are well-defined, multiloculated, cystic, middle mediastinal masses with irregular capsular walls and septa, which may enhance. Mature tumors often are completely solid. Ossification, calcification, and fat deposits, often visible as a fat–fluid level, are observed in 50%. Teratoma with additional malignant components (TAMC) typically is an ill-defined, large, thick-capsulated mediastinal mass.

Heterogeneous attenuation is indicative of hemorrhage and necrosis.

Infiltration of mediastinal fat, vessels, and airways is often observed. |

Teratoma is a GCT of young adults (20—30 y).

It represents > 70% of all GCTs and occurs as three subtypes. Mature teratoma is a well-differentiated benign tumor and is the most common type. Immature teratoma consists of < 10% mesenchymal and neuroectodermal tissue. TAMC is a very aggressive subtype. Its primary denomination as “malignant teratoma” or “teratocarcinoma” is no longer used. Mature teratomas are usually asymptomatic and have an excellent prognosis. Immature teratoma is equally asymptomatic but may be a little more aggressive. TAMC is a very aggressive neoplasm with poor prognosis due to an insufficient response to chemotherapy. All types are occasionally also found in the anterior and posterior mediastinum. |

Seminoma (germinoma) |

GCT, histologically consisting of uniform sheets of lymphocytes and round cells.

Diagnostic pearls: Large, well-defined lobulated mass in the middle or anterior mediastinum. May be homogeneous or contain low-attenuation areas. Tends to extend to the left of midline. Calcification, necrosis, or invasion is uncommon. Discrete attenuation on postcontrast scans. |

Represents 15% to 20% of all GCTs; has a peak in the third decade of life and is almost exclusively restricted to men. It is the most common malignant mediastinal GCT. Chest pain or respiratory symptoms are typical clinical complaints. Metastases to bone and lungs are common. Highly radiosensitive. |

Nonseminomatous germ cell tumor (NSGCT) (embryonal cell carcinoma, choriocarcinoma, mixed cell tumors, etc.) |

NSCGT is a nomenclature for all GCTs that are not teratomas or seminomas.

Diagnostic pearls: Large, ill-defined, lobulated anterior mediastinal mass with heterogeneous attenuation depending on predominant soft tissue component. Central hypodensities and calcification may occur with heterogeneous contrast enhancement. May displace or infiltrate mediastinal structures. Often concomitant pleural or pericardial effusion. |

GCTs are a mixed group of neoplasms. They have a common histologic origin from the three primitive germ cell layers. Histologic features depend on tumor subtype. About 15% of patients with NSGCTs present clinically with Klinefelter syndrome. Patients often have an elevated serum alpha fetoprotein level. Clinical symptoms include chest pain and dyspnea.

Overall prognosis is poor, particularly in the presence of mediastinal invasion or pleural/pericardial effusion. |

Neoplastic/thyroid and parathyroid tumors |

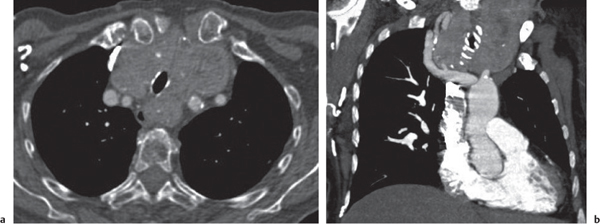

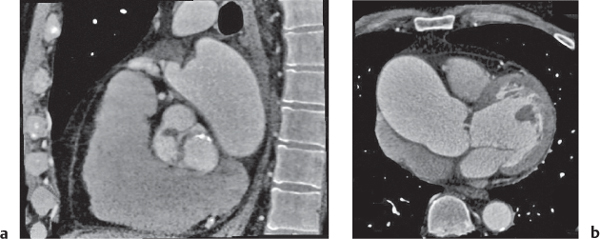

Goiter

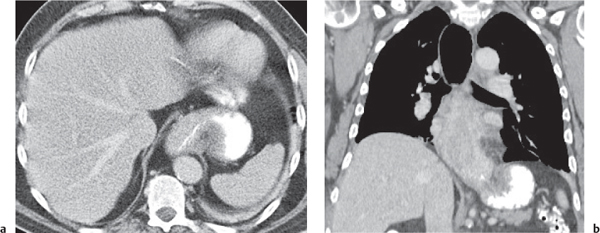

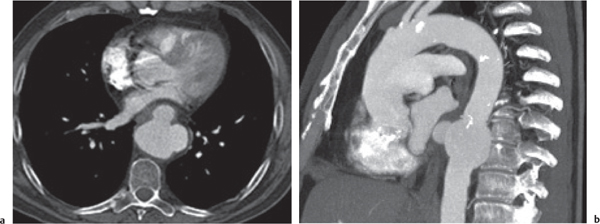

Fig. 18.22a, b |

Also denominated mediastinal or substernal goiter.

Diagnostic pearls: Well-defined heterogeneous mass. May deviate the trachea and displace mediastinal vessels. Focal calcification is common. Precontrast attenuation is over 100 HU; enhances intensely. |

Primary goiter due to migration anomaly and thus separate from thyroid gland. Secondary due to diffuse enlargement of thyroid gland and thus contiguous with the organ.

Represents 10% of all mediastinal masses; 75% to 80% in the anterior mediastinum, 20% to 25% in the posterior mediastinum. |

Intrathoracic thyroid carcinoma |

Substernal/mediastinal expansion of a primary thyroid malignancy.

Diagnostic pearls: Well- to ill-defined anterior mediastinal mass, slightly hyperdense on precontrast scans with a heterogeneous or peripheral postcontrast attenuation. May contain calcifications and hemorrhage (like benign lesions). Necrosis is present in > 50% and lymphadenopathy in 75% of cases. |

Papillary thyroid carcinoma is the most common malignancy. It spreads locally via lymphatics. Follicular thyroid carcinoma occurs in adults and metastasizes hematogenously.

Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma represents 4% to 15% of thyroid malignancies in the seventh decade of life. It is a rapidly enlarging mass causing tracheal obstruction and symptoms at an early stage. |

Medullary carcinoma of the thyroid |

Medullary carcinoma of the thyroid is a distinct thyroid carcinoma originating in the parafollicular C cells of the thyroid gland.

Diagnostic pearls: On postcontrast scans, a low-density mediastinal nodule is seen; visible within strongly enhancing thyroid tissue if the gland extends as far caudally. |

C cells produce calcitonin. Often occurs in conjunction with multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome II (MEN II).

Tumor measures between 2 and 26 mm and may occur anywhere from the neck to the mediastinum. |

Ectopic parathyroid gland |

Ectopic location of the parathyroid gland.

Diagnostic pearls: Well-defined round and on pre-contrast scans hypodense mass of 1 to 2 cm resembling a lymph node.

On postcontrast scans, homogeneous attenuation between 60 and 70 HU as compared with lymph nodes with either > 90 and attenuation or a clearly visible central fat pad. |

Of patients undergoing surgery for hyperparathyroidism, 22% present with an ectopic parathyroid gland. Eighty-one percent of those are localized in the anterior mediastinum. The tumor size usually correlates with the level of hypercalcemia.

Technetium 99m-labeled sestamibi and tetrofosmin tomography are the imaging modalities of choice, but CT may be useful for surgical planning. |

Neoplastic/other primary tumors and tumorlike lesions |

Lipomatosis

Fig. 18.23 |

Excessive fat deposition within the mediastinum.

Diagnostic pearls: Diffusely enlarged mediastinum due to smooth, symmetric, sometimes lobulated accumulation of fat in the mediastinum. Pleuropericardial fat pads are commonly enlarged. |

Usually associated with Cushing syndrome or long-term corticosteroid therapy, occasionally with simple obesity. |

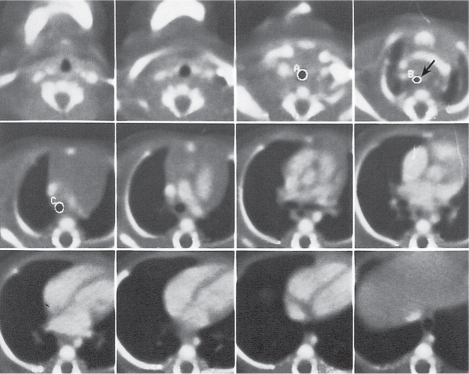

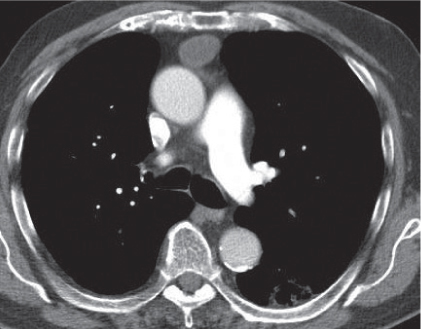

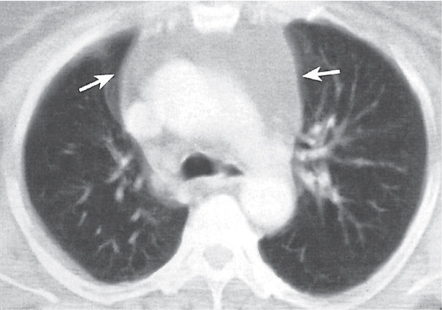

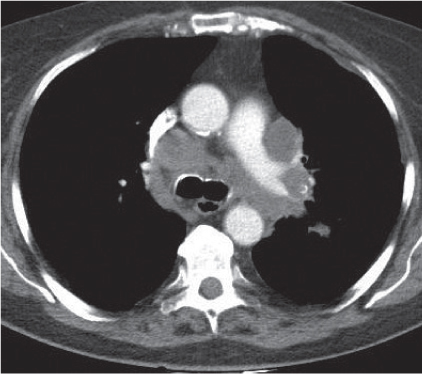

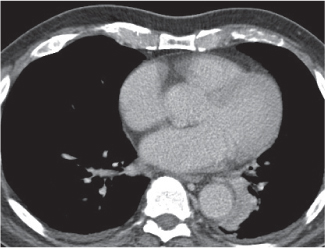

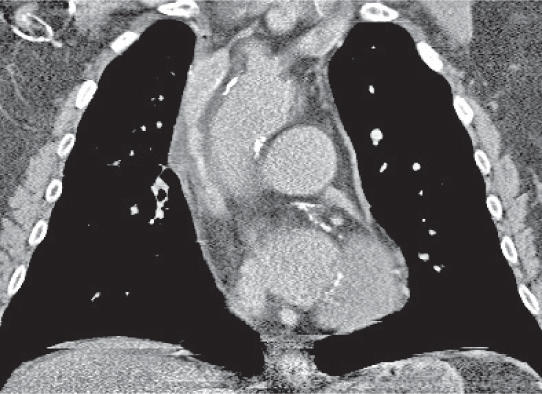

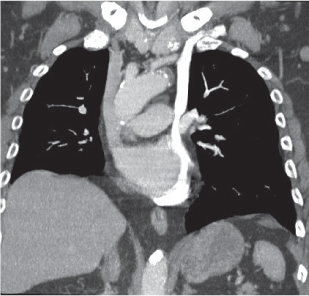

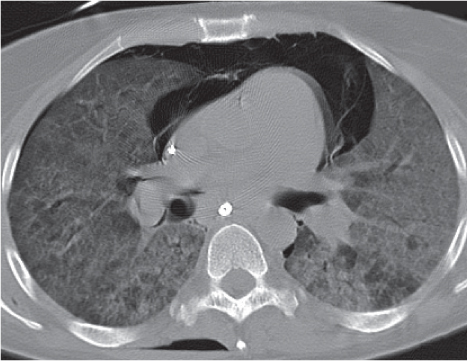

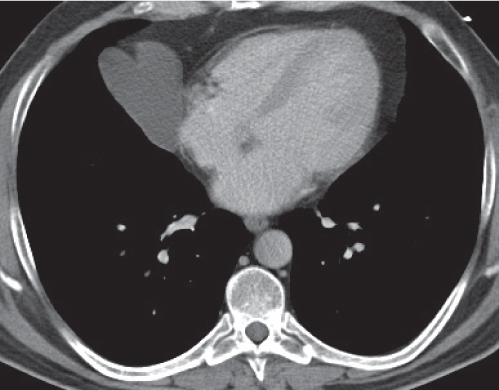

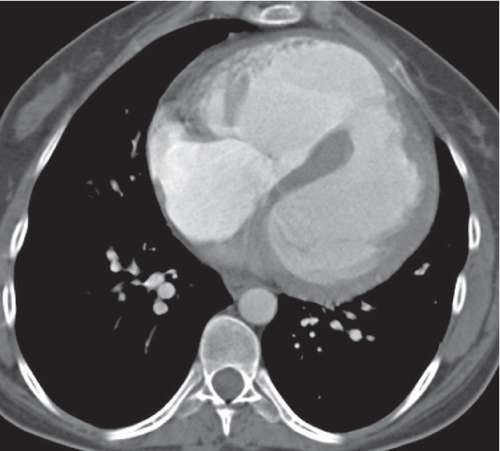

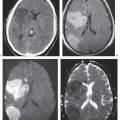

Lymphoma

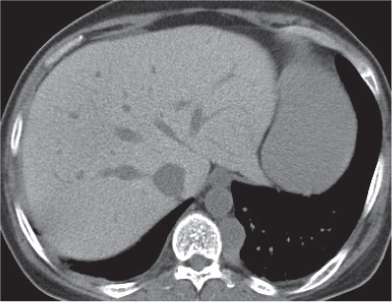

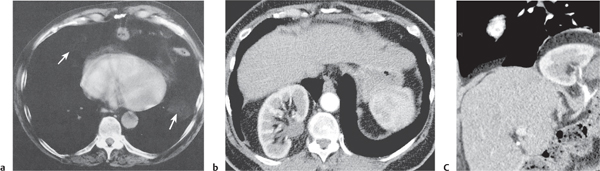

Fig. 18.24

Fig. 18.25 |

Mediastinal lymphadenopathy due to Hodgkin (HL) or non–Hodgkin (NHL) lymphoma.

Diagnostic pearls: HL presents as a slightly inhomogeneous bulky mass in the anterior mediastinum. Attenuation on postcontrast scans is discrete. Involvement of multiple nodal groups is characteristic. NHL presents as a bulky mediastinal bilateral hilar mass with predilection of the superior mediastinum. Lymph node enlargement is more prominent in paratracheal, retrocrural, and paravertebral locations. Postcontrast attenuation of enlarged lymph nodes may be normal or decreased. |

Mediastinal involvement is more common in HL (> 50%) than in NHL (20%). Cervical and upper anterior lymph nodes are involved more often in HL. Involvement of paracardiac or lower posterior mediastinal nodes in HL is rare. |

Leukemia |

Comcomitant lymph node enlargement in leukemic patients.

Usually symmetric, modest enlargement of mediastinal and bronchopulmonary lymph nodes.

Diagnostic pearls: Round, homogeneous lymph nodes with slightly increased attenuation on postcontrast scans. |

More often observed in lymphocytic than in myelocytic leukemia. Often associated with pleural effusion and pulmonary parenchymal involvement. |

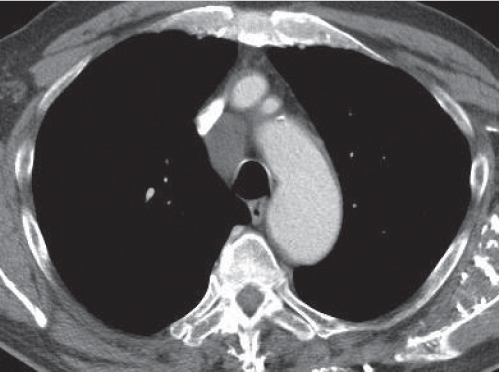

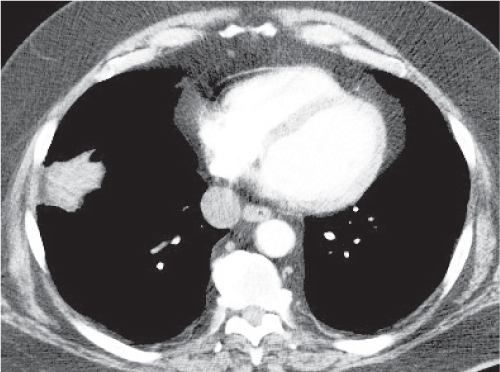

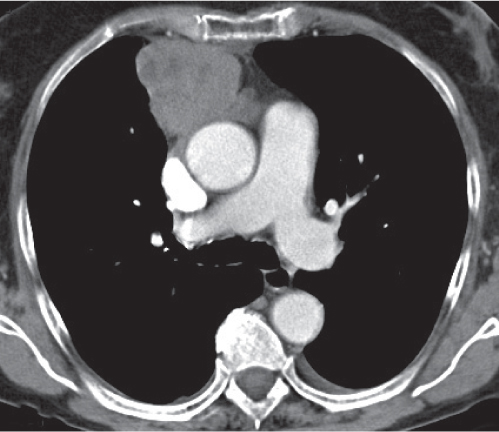

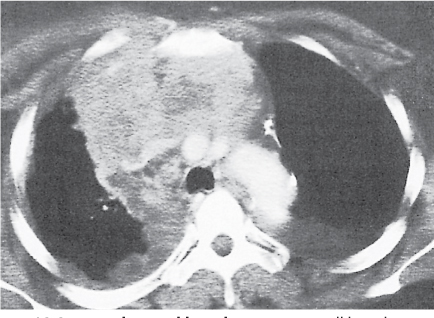

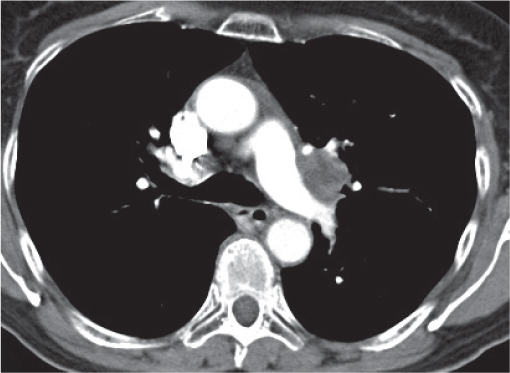

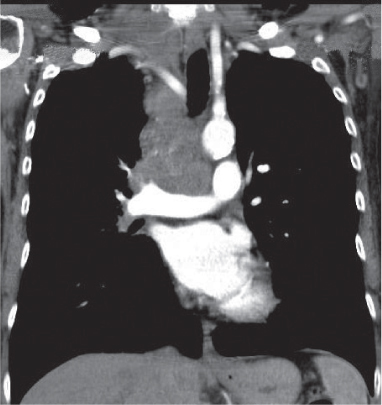

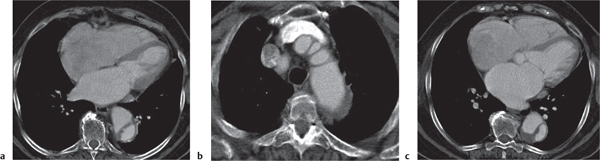

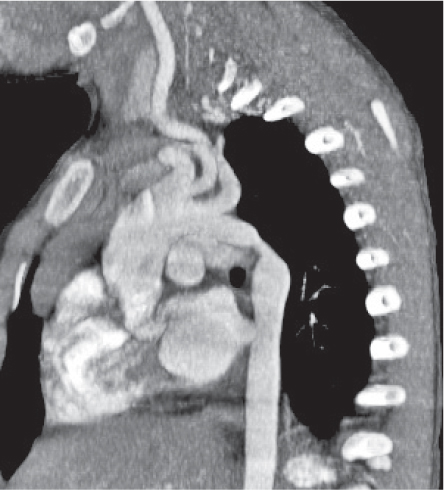

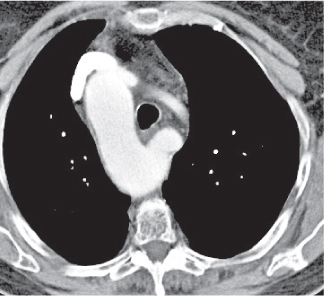

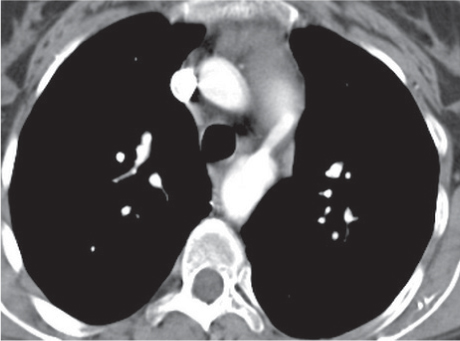

Lymph node metastases

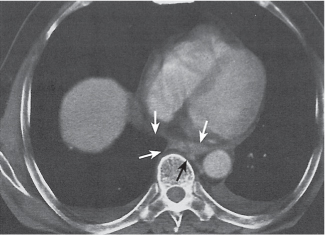

Fig. 18.26

Fig. 18.27 |

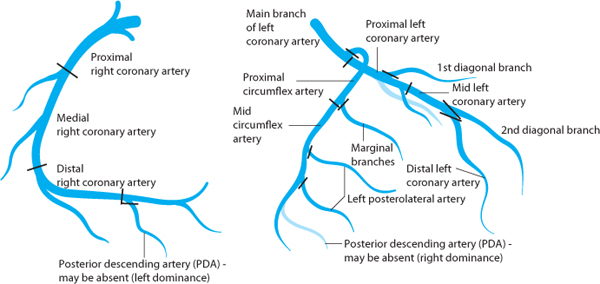

Lymph node enlargement due to lymphatic spread of malignant neoplasties.

Diagnostic pearls: Size of lymph nodes not indicative of presence or absence of metastases. Calcifications are observed in metastases from cartilaginous or osseous tumors, mucinous adenocarcinoma, or bronchoalveolar carcinoma. On postcontrast scans, pronounced enhancement is observed in metastatic lymph nodes of renal, thyroid, and choriocarcinoma. |

Bronchogenic carcinoma typically shows early spread to mediastinal lymph nodes. Even lymph nodes < 10 mm may contain micrometastases. Skip metastases (e.g., sparing of hilar lymph nodes)/contralateral lymph node metastases are observed. Any (near) round lymph node with a ratio of shortest/longest diameter near 1 and without central fat pad is highly suspicious, particularly if measuring > 10 mm in size. Other common primaries are head and neck tumors, breast cancer, renal carcinoma, and malignant melanoma. |

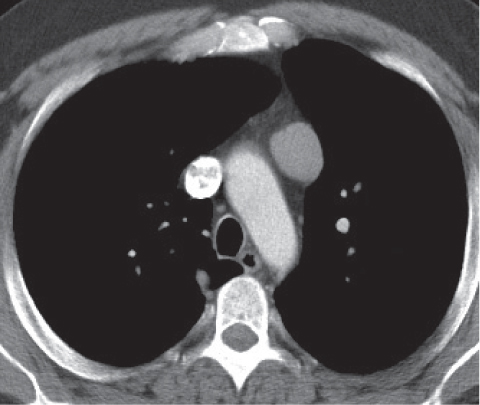

Giant cell lymph node hyperplasia (Castleman disease)

Fig. 18.28 |

Rare benign lymphoproliferative hyperplasia of lymph nodes.

Diagnostic pearls:

Localized type: Well-defined or lobulated enlarged lymph nodes with strong homogeneous attenuation on postcontrast scans. Inhomogeneous or ring enhancement is indicative of necrosis. No pulmonary involvement.

Multicentric type: Several large, sharply demarcated mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes, with concomitant abdominal and/or cervical lymphadenopathy, with moderate postcontrast enhancement. Lymphogenic pulmonary pattern (i.e., ill-defined centrilobular nodules, nodular septal thickening, ground-glass opacities). |

Histologically, hyaline vascular (90%), plasma cell (9%), or mixed types. Observed in middle-aged adults without any gender preponderance. Clinically, differentiation into a localized and multicentric type. Hyaline vascular types are usually localized and asymptomatic; plasma cell types, multicentric and symptomatic. In > 70% of cases, involvement of only the thorax; in 15%, also in the neck and/or abdomen. Localized forms may be treated by surgical resection; multicentric forms may need chemotherapy. |

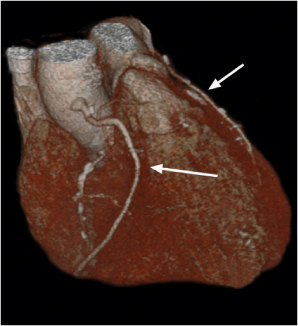

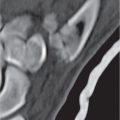

Neurogenic tumors

Fig. 18.29 |

Well-defined, round to oval posterior mediastinal mass.

Diagnostic pearls:

Nerve sheath tumors: Low-attenuation, well-defined, paravertebral soft tissue mass.

Calcifications and dumbbell appearance with a dilated neural foramen (extension into spinal canal) are observed in 10% to 15% of cases. Neoplasms usually show distinct, homogeneous enhancement, but may also have hypodense areas due to local necrosis. Sympathetic ganglion tumors: Ill-defined, typically longitudinally elongated paravertebral mass. Heterogeneous attenuation due to calcifications (ganglioneuromas/neuroblastomas), necrosis, hemorrhage, and cystic degeneration. Paragangliomas show strong homogeneous enhancement on postcontrast scans. |

Histologic differentiation between nerve sheath tumors (neurinoma, neurofibroma, schwannoma, peripheral nerve sheath tumor, etc.) and sympathetic ganglion tumors (paraganglioma, ganglioneuroma, neuroblastoma). Neurofibromas and neurinomas occur in young adults, sympathicoblastomas during early childhood. Except for the rare paragangliomas (localized along the sympathetic chain, vagus nerve, intracardial, etc.), all other neoplasms are found exclusively in the posterior mediastinum.

Paragangliomas are a form of extraadrenal pheochromocytoma and thus may present with a hypertonic crisis.

Bone destruction, invasion of mediastinal structures, and pleural effusion suggest malignancy; otherwise, CT features lack histologic specificity. |

Esophageal neoplasm

Fig. 18.30

Fig. 18.31a, b |

Localized bulging of the esophagus.

Diagnostic pearls: Short- to long-segment wall thickening and passage obstruction often associated with prestenotic dilation. Any eccentric wall thickening >3 to 5 mm in a distended esophagus is highly suspicious of a neoplasm. Ill-defined periesophageal fat planes suggest spread into surrounding structures. Contrast enhancement often is discrete but may improve the tumor delineation. |

Most commonly squamous cell carcinoma. Leiomyoma is located in the submucosa and thus typically appears as a smoothly marginated, homogeneously enhancing focal wall thickening. Inflammatory wall thickening of the esophagus may mimic a neoplasm but is usually more generalized. An esophageal diverticulum can be differentiated from a duplication cyst or necrotic neoplasm by oral contrast administration: a diverticulum is filled, but not a duplication cyst/neoplasm. Exact assessment of localization and longitudinal extension of the tumor, involvement of regional lymph nodes, local invasion (i.e., periesophageal fat stranding), and distant metastases is highly important for planning further therapeutic procedures. |

Miscellaneous |

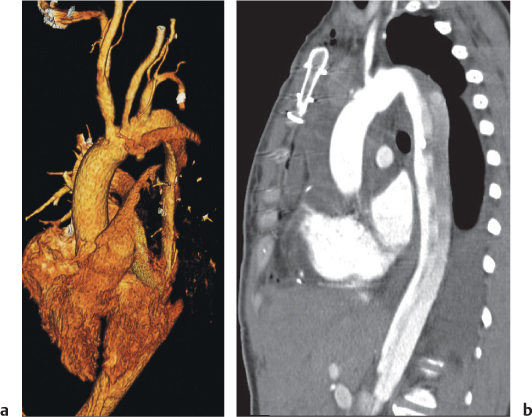

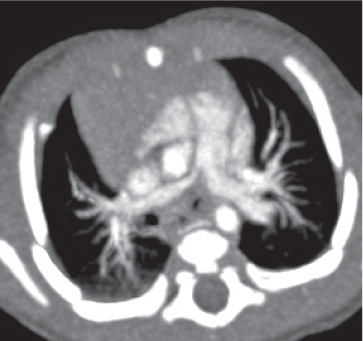

Diaphragmatic hernias

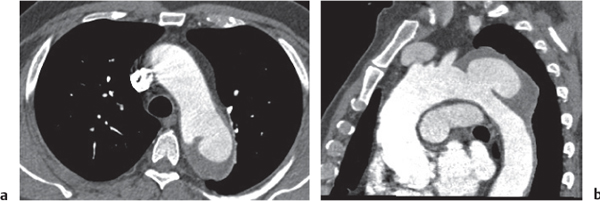

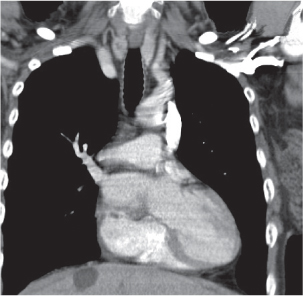

Fig. 18.32 a–c |

Hernia through either the foramen of Morgagni or Bochdalek hernia.

Morgagni hernia is characterized by a fat-density mass in the right cardiophrenic angle. Contains fine linear densities, which represent omental vessels. Bochdalek hernia typically is left posterolateral (>80%), large, and associated with organs (kidney, spleen, bowel, stomach, liver, etc.). |

Uncommon diaphragmatic hernias through the foramen of Morgagni, which is a small triangular sternocostal zone lying between the costal and sternal attachments of the thoracic diaphragm. Demonstration of omental vessels helps in distinguishing Morgagni hernia from a pericardial fat pad. Bochdalek hernia accounts for >80% of all nonhiatal hernias and is caused by a failure of closure of the pleuroperitoneal cavity. |

Esophageal hiatal hernia |

Protrusion of (part) of the stomach through the esophageal hiatus of the diaphragm.

Diagnostic pearls: Axial hernias often resemble esophageal masses. A second contrast-filled lumen lateral to the distal esophagus is always indicative of paraesophageal hernia. Best visualized on coronal reformations.

Rule out other cystic mediastinal masses (see also Fig. 24.9 , p. 745). |

Common in elderly and overweight patients.

Perigastric fat may herniate through the esophageal hiatus without the stomach proper.

Axial (sliding) hernias must be differentiated from paraesophageal hernias. In axial hernias, the gastroesophageal (GE) junction and the cardia are displaced intrathoracically. In paraesophageal hernias, the fundus with or without the GE junction is displaced intrathoracically. |

Extramedullary hematopoiesis

Fig. 18.33 |

Hematopoiesis occurring outside the medulla of the bone.

Diagnostic pearls: Paravertebral soft tissue masses in the lower half of the thorax. May appear as fat-density masses. |

More frequently associated with pathologic processes, such as myelofibrosis. Extramedullary hematopoiesis occurs typically with a characteristic purpura (“blueberry muffin” baby) in congenital hemolytic anemias (hereditary spherocytosis, thalassemia, sickle cell anemia, or TORCH [ toxoplasmosis, other agents, rubella, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex] infections). |