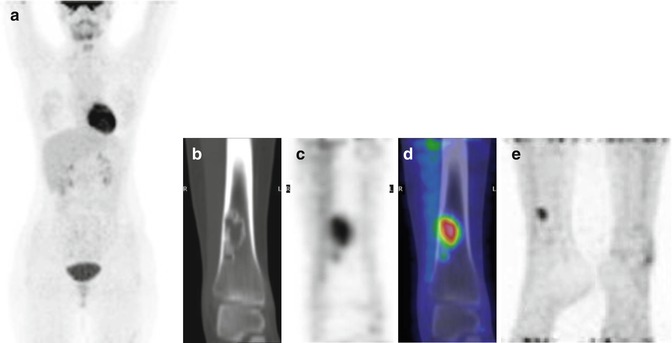

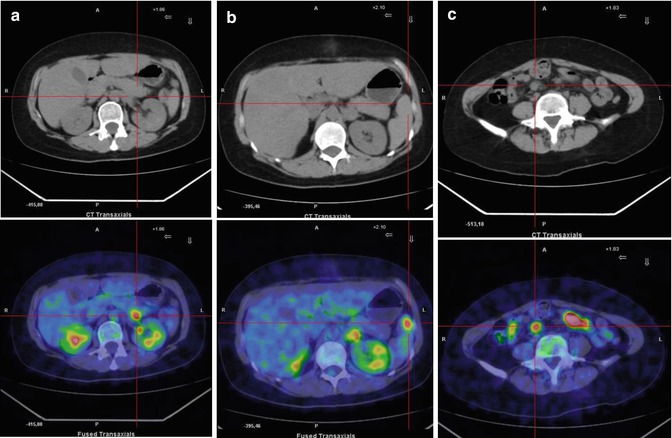

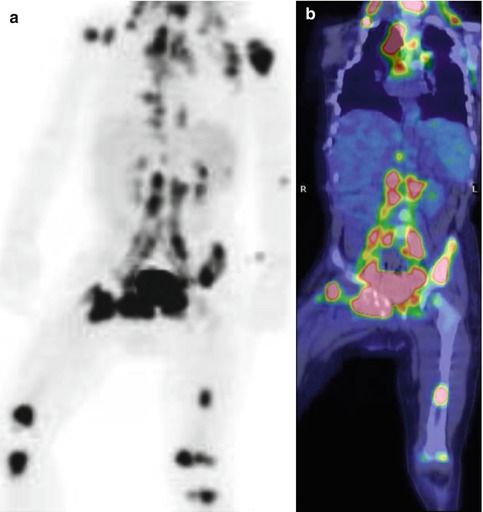

Fig. 6.1

A 15-year-old girl with Hodgkin’s disease. Coronal CT (a), PET (b), PET/CT fusion (c), and maximum intensity projection (d) staging images show multiple sites of uptake in the supradiaphragmatic lymph nodes, indicative of stage II disease

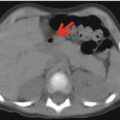

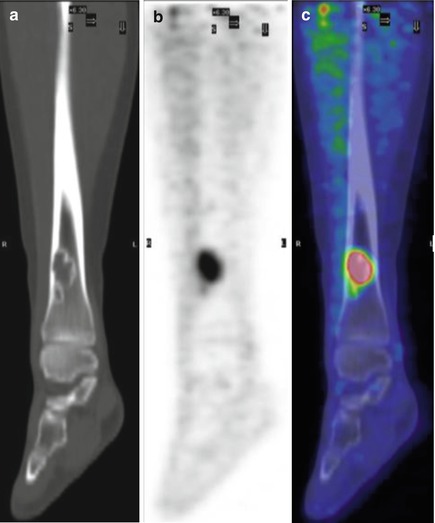

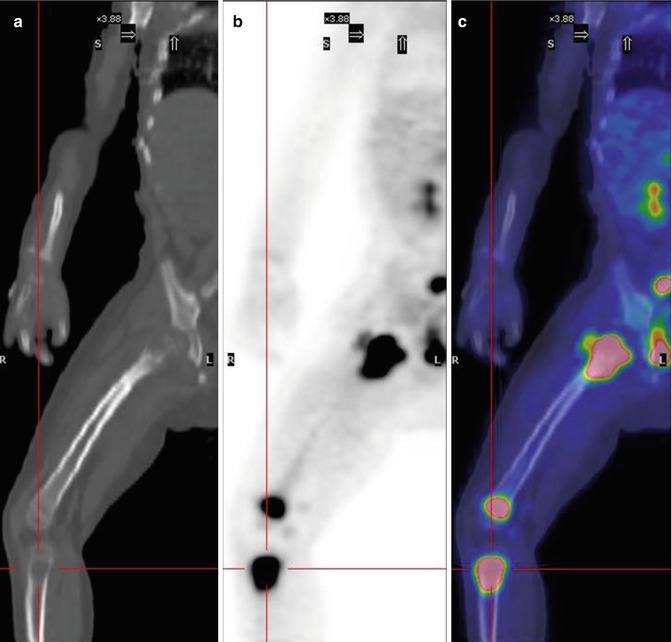

Fig. 6.2

Same patient as in Fig. 6.1. Coronal CT, PET, and PET/CT fusion images of the right tibia. The coronally reformatted CT (a) shows a lucent lesion in the distal right tibia, corresponding to increased uptake on coronal 18F-FDG–PET (b) and 18F-FDG–PET/CT fusion images (c). The disease stage has changed from stage II to stage IV based on osseous involvement

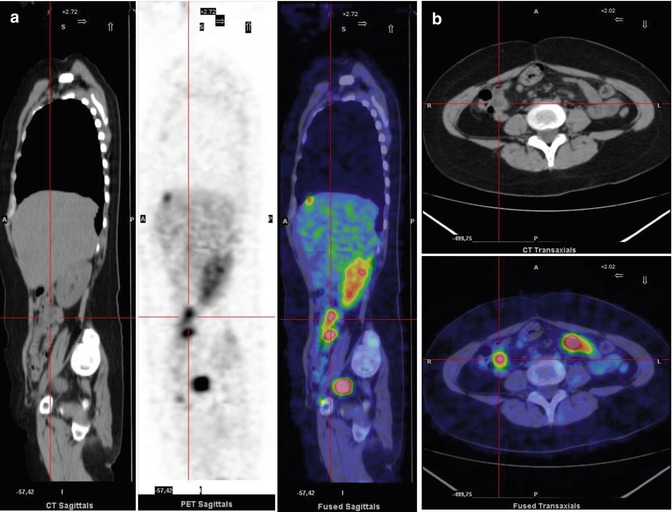

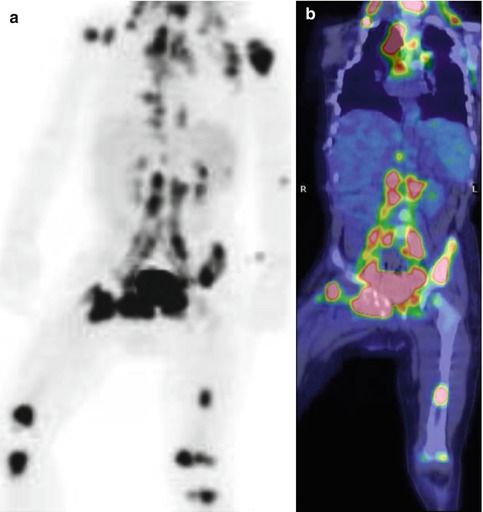

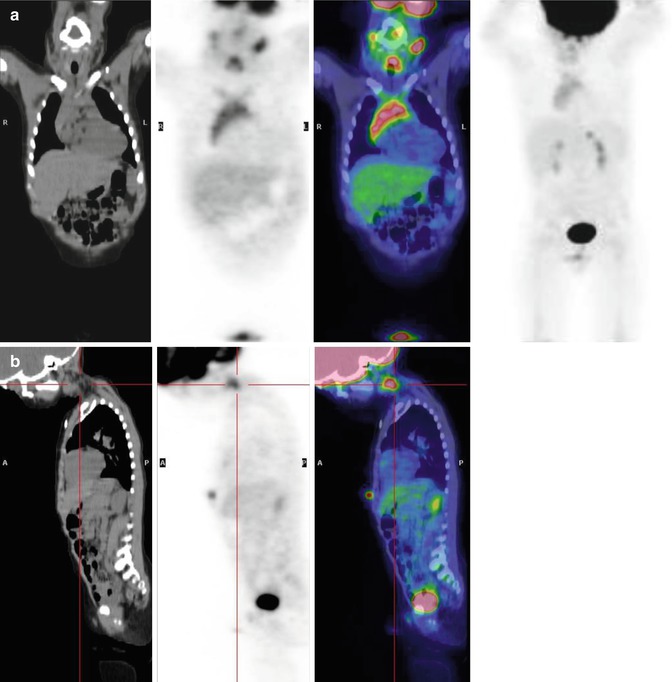

Fig. 6.3

Same patient as above. The PET study during chemotherapy showed complete resolution of the lymph node uptake, as seen on MIP (a). Coronal CT shows unchanged lucent tibial lesion (b) while persistent uptake of 18F-FDG in the tibia is seen on PET (c) and PET/CT fusion (d). The evaluation at the end of treatment indicated complete lymphoma remission. Tibial uptake was unchanged on emission PET (e)

In the case presented in Figs. 6.1, 6.2, and 6.3, radiography of the tibias revealed findings consistent with nonossifying fibroma. This benign condition, which is commonly encountered in radiology, is a well-circumscribed solitary proliferation of fibrous tissue usually located in the metaphysis or diametaphyseal junction of the femur or tibia. It appears as an eccentric radiolucent lesion with thinned cortex, which can have a multilocular appearance and often a sclerotic margin [1]. During the involutional phase, osteoblastic activity increases as the lesion is replaced by new bone. The mechanism for 18F-FDG uptake by nonossifying fibroma and acute fractures may be similar, as the two shares increased blood flow as well as osteoblastic and metabolic activity [2]. In general, nonossifying fibroma regresses spontaneously.

Teaching Point

Case 2

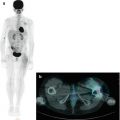

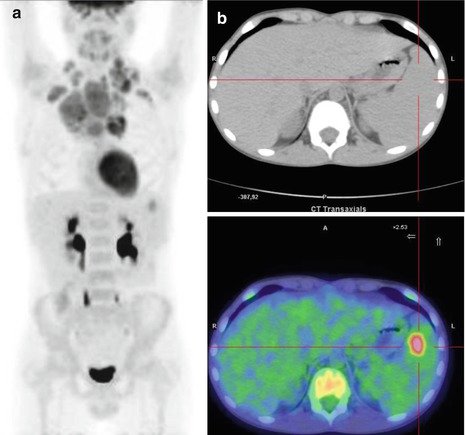

Fig. 6.4

An 11-year-old boy with Hodgkin’s disease. (a) Maximum intensity projection 18F-FDG–PET image shows multiple uptake sites in the supradiaphragmatic lymph nodes. (b) Axial CT and PET/CT fusion images show involvement of the spleen. The final stage of the tumor was IIIs

Case 3

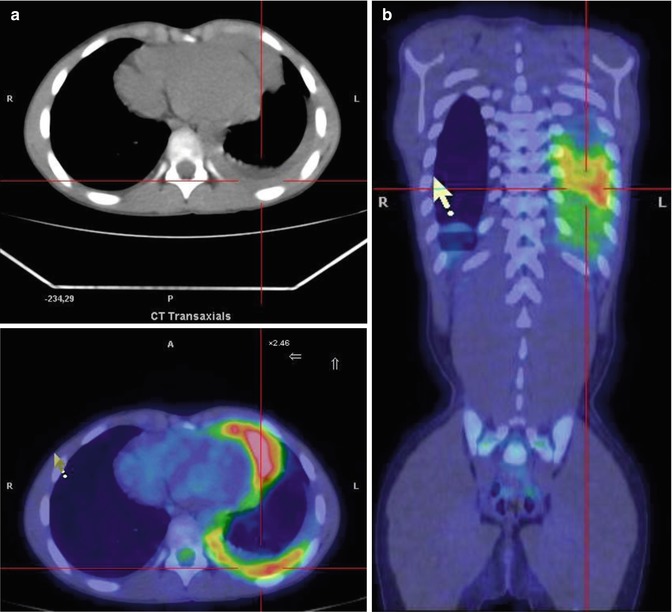

Fig. 6.5

A 9-year-old boy with stage IV Hodgkin’s disease. (a, b) Axial CT together with axial and coronal PET/CT fusion images show posterior left pleural involvement

Case 4

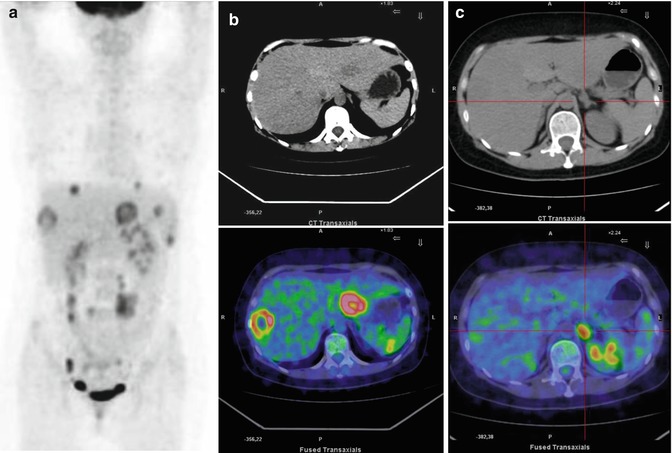

Fig. 6.6

A 17-year-old girl diagnosed with diffuse large cell lymphoma, an aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma that often involves the lymph nodes, spleen, liver, bone marrow, and other organs. Maximum intensity projection (a) and axial CT and PET/CT fusion images (b,c) show liver lesions with central necrosis (b) and lesion of the left adrenal gland (c)

Fig. 6.7

Same patient as in Fig. 6.6. (a–c) Axial CT and PET/CT fusion images show lesions of the pancreatic tail (a) and spleen (b) as well as mesenteric lymph node involvement (c)

Fig. 6.8

The same patient as above. (a) Sagittal-view CT, PET, and PET/CT fusion images show bowel involvement. (b) Axial CT and PET/CT fusion images show 18F-FDG uptake in the small bowel

Fig. 6.9

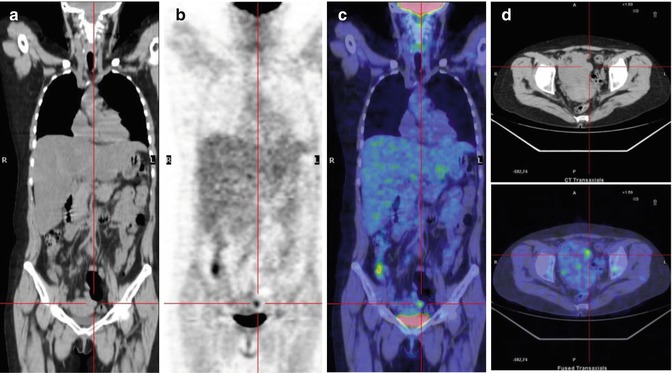

The same patient during chemotherapy treatment. Coronal CT (a), PET (b), and PET/CT fusion images (c) show the disappearance of all pathological uptake. A hot spot is visible in the left pelvis (c), which as seen on axial CT and PET/CT fusion images (d) is due to a physiological ovarian follicle

Teaching Point

Case 5

A 2-year-old boy presented with fever, right knee pain, and lameness, previously treated with antibiotics and low-dose betamethasone. The radiological finding suggested osteoarthritis of the right hip joint with involvement of the adjacent muscles, nonresponsive to antibiotics. An arthrotomy of the right hip joint was performed: the microbiological studies were negative. Ultrasound imaging of the soft tissue of the neck showed small laterocervical bilateral lymph node adenopathy, without colliquation. A PET/CT study was requested to metabolically characterize both the hip lesions and the laterocervical lymph adenopathy (Figs. 6.10, 6.11, 6.12, 6.13, 6.14, 6.15, and 6.16).

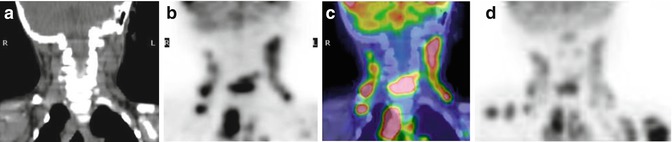

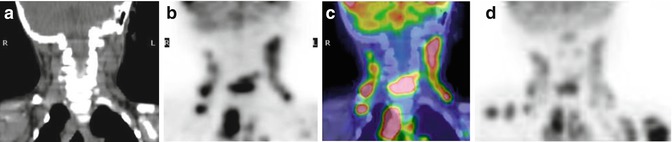

Fig. 6.10

Coronal CT (a), PET (b), PET/CT fusion images (c), and maximum intensity projection (d) of the head–neck region showing extensive 18F-FDG uptake in the laterocervical lymph nodes and a lesion in the fifth cervical vertebra

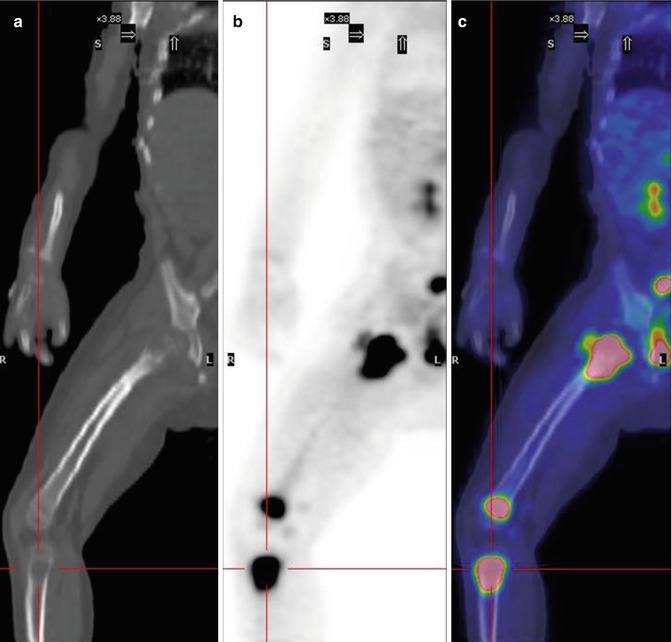

Fig. 6.11

Same patient as in Fig. 6.10. Coronal CT (a), PET (b), and PET/CT fusion (c) images show intense uptake in the proximal and distal right femur as well as in the proximal right tibia

Fig. 6.12

Same patient as above. Maximum intensity projection (a) and coronal PET/CT fusion (b) images show multiple sites of uptake in the pelvic bone, proximal humerus, right scapula, and sternum. Multiple pathological supra- and subdiaphragmatic lymph nodes are also present. A PET-guided biopsy of a laterocervical lymph node confirmed the diagnosis of t(2;5)-positive anaplastic large cell lymphoma, stage IV

Teaching Point

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma may have a silent onset and involve several organ systems, including bone. In this patient, the condition was initially suspected to be benign. Conventional imaging methods, generally used to evaluate the extent of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, did not identify the malignant characteristics of the hip joint lesion. PET/CT can be a useful tool in the metabolic characterization of lesions of unknown origin. It improves their localization, and allows a guided biopsy, by identifying the more accessible and active sites, and thus increases the diagnostic success rate.

Fig. 6.13

The same patient at the end of the therapy according to the Italian chemotherapy protocol for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (ALCL AIEOP 99). (a) Coronal CT, PET, and PET/CT fusion images and maximum intensity projection show complete disease remission, with the disappearance of all bone and lymph node uptake. Note the intense uptake in the anterior mediastinum, due to hyperplasia of the thymus. (b) Asymmetric uptake is visible in the left laterocervical region but without corresponding morphological alterations on CT. This site corresponds to brown fat activation

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree