2

Correctly Using Imaging for Your Patients

Wilbur L. Smith

Chapter Outline

Chapter Outline

IMAGING APPROPRIATELY

Modern medicine is confusing both for patients and physicians. Imaging tests are essential to make or confirm many diagnoses but the plethora of possibilities and the heightened patient diagnostic expectations confound everyone. Just look at media where you can see actors posing as “doctors” performing and reading their own MRI studies to make a rare diagnosis and administer the unique curative drug that they just happen to have in their desk drawer. We all know it is either fiction or advertising, but it is what the public has come to expect. The complexity of imaging examination’s technical performance, sequencing, and selection is the subject of reams of studies and the object of years of training. Have you ever looked at the control panel for a modern CT or MRI scanner? Could you turn it on without fear of blowing the whole place up, let alone assure the proper examination sequences and time the contrast administration? Enough said, the message is getting the right imaging examination for your patient performed in a competent and diagnostic manner requires teamwork and consultation, so let us consider the process.

First, there has to be recognition of your patient’s need for a study. Sometimes this is easy and straightforward; a patient comes to you with cough and fever and you hear rales in his chest. A simple chest x-ray is likely the imaging of choice as there is a high clinical probability that the patient has pneumonia. Great so far, no need for elaborate consultation, get the test and when it is interpreted as positive, treat. But let us say that after a couple of days of improvement on antibiotics the patient comes back a week later clinically worse with the return of the initial symptoms. What now, should you change antibiotics, put on a TB skin test, and/or consider more imaging? Perhaps now it is time to consult but with whom: Infectious disease expert or the radiologist? Each offers a valuable perspective and, most importantly, can help you do the “right thing” for your patient. The radiologist upon review may see a hilar mass which he/she originally thought a lymph node but now thinks may be an endobronchial lesion causing a postobstructive pneumonia. In that case, the antibiotic change suggested by infectious disease consultation is unlikely to be of much value and a definitive CT would be best. On the other hand, if the mass was a lymph node the TB skin test that the infectious disease expert suggested is a great idea. The point is that there is no shame in seeking help; we are not all the great TV doctors who are wise and omniscient. Our patients are also not TV patients who have rare and exotic diseases where the more tests the better regardless of whether they or society can afford them.

The critical assessment of using the correct imaging modality for the correct patient for the correct reason is everyone’s concern. Imaging is expensive, carries some risk, and if inappropriately applied may lead to either false-positive or falsely reassuring results. An unnecessary test, particularly in the older population often results in findings called “Incidentalomas.” An “Incidentaloma” is defined as a finding of questionable significance which is not related to the reason for performing the test in the first place. One retrospective study showed that individuals over the age of 70 years will almost invariably have an “Incidentaloma” finding on an abdomen and pelvis CT scan and that the older the patient the greater the number of “Incidentalomas” per patient will be discovered. “Incidentalomas” often result in a plethora of further unnecessary tests or treatments. Fortunately, the harm done is usually economic and perhaps societal owing to increased radiation dose but occasionally a false-positive finding results in surgery or a diagnostic disaster such as a serious contrast reaction. Always question results unrelated to the reason an examination was performed in the first place. Sometimes incidental findings are critical or may affect future care but more often they are “Incidentalomas.”

The next rule of appropriate imaging is using your radiologist as a consultant. You would not think of spending $2,000 without knowing what you were getting for it but when you request an MRI without careful consideration that is exactly what you are doing. Radiologists spend a lot of time learning the strengths and limitations of their tools; not taking advantage of that experience is unwise. One of the functions that you should demand of your radiology service is the ability to provide a prospective consultation on the proper sequencing of examinations, utility of examinations, and risks of examinations. How else can you provide your patients with the highest levels of care? Radiologists who spend years of their lives learning to recommend the appropriate imaging are happy to talk to you for free. What a bargain in today’s healthcare. It seems an oxymoron that radiologists by consulting often serve counter to their direct economic interests by discouraging performance of unnecessary tests. Consider an example; you obtain a chest radiograph on a 28-year-old man who was otherwise healthy but had chest wall trauma. The radiograph is negative for fractures but shows a 3-mm diameter nodule in the right upper lobe. What does that mean? Unless you are familiar with the literature on pulmonary nodules your first call should be to the radiologist before you order a chest CT or other expensive imaging. Hopefully, the radiologist would ask you if the patient is high or low risk for malignancy (read heavy smoker) and if low risk tell you not to do any more imaging. If high risk, a follow-up chest x-ray in 12 months is a good recommendation and may well suffice to deal with the issue. In either case your patient and the healthcare system are better served than had you immediately requested a chest CT. I know it seems an economic paradox but most radiologists would prefer not to perform a nonindicated examination.

Not all questions are as easily dealt with as the simple chest nodule and the American College of Radiology (ACR) has responded to the need for appropriate imaging by forming multidisciplinary committees to assess the value of imaging for multiple clinical scenarios and conditions. These recommendations are developed by expert panels using literature review, clinician experts and subspecialty expert radiologists to rate the appropriateness of imaging for many clinical situations. The recommendations are free, online, and open to all, including your patients, on the ACR.org website. The recommendations include a numerical assessment of appropriateness of various types of imaging as well as a relative scale of radiation dose from the study. There is now a movement to build these criteria into the decision-making algorithms of the electronic medical record. This means that before ordering an examination you would automatically be presented with queries as to whether or not the examination you requested was appropriate for the clinical situation. Of course no appropriateness criteria can be encyclopedic and these may be good reasons to deviate from the ACR criteria, but at least knowing about them and consulting the radiologist will give you a solid basis for decision making.

One of the other key adverse effects of an unnecessary test is ionizing radiation. The cancer scare has probably been overdone on an individual basis but there is a real risk of increased ionizing radiation exposure to the population gene pool as opposed to the individual. The next section of this chapter deals with a simple and practical approach to understanding the risks of diagnostic test radiation exposure.

RADIATION PROTECTION

Radiation exposure owing to diagnostic imaging is everyone’s concern, the challenge is to keep this concern in the proper perspective; hysteria often trumps reason. If a patient has a potentially serious condition that cannot be diagnosed without radiation-based imaging, then there should be no hesitation, do the imaging! On the other hand, if the diagnosis is highly unlikely after reviewing the whole clinical picture, or if an equally efficacious means of making the diagnosis exists without using ionizing radiation (MRI, ultrasound, or nonimaging test), then avoid x-ray–based testing. Several factors must be assessed but remember an un-indicated test is likely to lead to a false-positive finding! False-positive findings never do anyone any good and can cost a lot of money or pain to disprove. Remember the most effective patient radiation protection is not to do an unnecessary test!

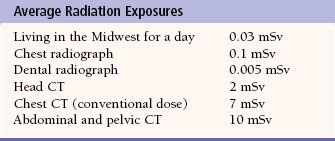

Now let us assume that you have analyzed the situation and the test is really needed; what is next? You need to know enough of the language of radiation protection to explain the need for the test and the risks. Remember your patient has been on the internet and seen all the stories about radiation overexposure. In fact the Environmental Protection Agency website has a fancy do it yourself radiation calculator where you plug in such factors as airplane trips and geographic area of your domicile as well as your medical exposure to calculate your annual radiation exposure. With all this data it is almost certain your patient will have questions regarding the procedure and the level of radiation exposure for a study. All x-ray studies do not involve equal radiation doses and a sense of proportion is important. Table 2.2 demonstrates the doses from several common imaging examinations. Comparing these doses to the background radiation from just existing on earth is often helpful in explaining radiation safety for your patients. As you can readily see CT is the major medical source of radiation exposure for the United States’ population.

Table 2.1

In order to respond effectively to your patient’s questions, knowing indications for CT imaging as well as the advantages of CT as compared to other imaging modalities (Table 2.1) is helpful. Your local radiologist is always a valuable resource to help answer these questions. Remember, it is not your job to be all knowing, just how to find the right information at the right time for the patient. That said it always helps to understand the language and to answer questions as to the safety of procedure when your patients ask.

If the radiation-based test is necessary you need to understand the concept of ALARA (as little as reasonably acceptable). This concept, based on the old axiom of do no harm, is useful in other areas as well as radiation safety, but is particularly apt in the radiology protection arena. For any examination using ionizing radiation the technique is adjustable and will affect the total radiation dose. Here you need to know two terms, the milligray (mGy) and the millisievert (mSv). These terms are related but very different. Milligray is a measure of ionization and strictly speaking is an ion chamber value of how much ionizing radiation is applied while mSv is a measure corrected for the biologic effect on tissues in the course of the beam. Think of it this way, the same amount of ionizing radiation (mGy) applied to a radiosensitive tissue such as the lens of the eye will cause more damage than the same mGy hitting an insensitive tissue such as the bones of the orbit. The Sievert is the more critical measure but the Gray is the most frequently reported. The reason for that is simple, most radiation-producing diagnostic machines report Gray directly at the end of the examination. That said using high-dose techniques in the diagnostic radiology ranges will almost certainly guarantee prettier pictures, but how “pretty” do the images need to be in order to make the diagnosis? The recent interest in monitoring CT doses and the mandatory accreditation of CT facilities is a step in the right direction although it is not as simple as it sounds. The radiologist and radiology professionals must constantly monitor the facility and equipment to ensure optimal performance. This is where ALARA comes in; using only the minimum radiation dose technique needed to make the diagnosis is optimally the ALARA principle. How do we achieve that, by adjusting techniques so that we give lower dose, by scanning only the tissues in question, and by using the best radiation protection of all … NOT DOING UNNECESSARY EXAMINATIONS.

After you protect your patient, you need to protect yourself. A single view chest x-ray, even if it is aimed right at you, is only slightly more than a day’s exposure from natural background and about equal to the radiation from a 4-hour airplane ride. While the dose from a single radiograph is small, the cumulative dose especially for someone working with x-rays on a daily basis can be significant. Fluoroscopy, which continuously generates x-rays, can have substantially more radiation exposure resulting in skin damaging doses to both the patient and unshielded personnel. Whenever you work in a radiation area be sure you wear your protective garb and you put on your radiation monitoring badge.

Pediatric patients and pregnant patients are a special concern. Kids have longer anticipated lives, exposing them to potential cancer induction and germ cell genetic mutations induced by radiation will likely carry throughout their reproductive lives. The Society for Pediatric Radiology recognized this and initiated an “Image Gently” program which has had measurable success in applying the ALARA principles to pediatric imaging. Clearly there is a risk benefit analysis which is needed for any use of ionizing radiation but in kids, there is extra need for consideration of alternative to imaging with ionizing radiation. In pregnancy the greatest concern is in the period of organogenesis during the first and early second trimesters. Third trimester fetuses are pretty radiation resistant. If you should get into a question of radiation protection in pregnancy be sure to consult your radiologist, preferably before exposing the patient.

Key Points

Key Points

• If the simple first test does not solve the issue, consult someone else.

• Radiologists and specialist clinicians each bring a different and valuable approach to a diagnostic dilemma; having both benefits your patient.

• Unnecessary imaging examinations often result in false-positive findings. These can be dangerous!

• ALARA is the key to decisions on using ionizing radiation wisely.

• Children and early pregnancy fetuses are at far greater risk from diagnostic radiation’s long-term ill effects than adults.

FURTHER READINGS

1. Patient safety. RadiologyInfo.org Web site. http://www.radiologyinfo.org/en/safety/index.cfm. Accessed March 4, 2013.

2. Radiation: Non-ionizing and ionizing. United States Environmental Protection Agency Web site. http://www.epa.gov/radiation/understand. Updated August 7, 2012. Accessed March 4, 2013.

3. Stabin MG. Doses from medical radiation sources. Health Physics Society Web site. http://hps.org/hpspublications/articles/dosesfrommedicalradiation.html. Updated March 4, 2013. Accessed March 4, 2013.

QUESTIONS

QUESTIONS

1. True or false: Consultation and interpretation are expected services of a Radiology department.

2. True or false: Federal guidelines requiring certification of CT facilities assure compliance with ALARA principles.

3. True or false: Radiation exposure from a chest radiograph is about quadruple the exposure from living a day on earth.

4. True or false: Most humans over the age of 70 years will have at least one incidental finding on an abdomen and pelvis CT.

5. True or false: Diagnostic radiation exposure in adults over the age of 70 years is likely to cause an excessive incidence of cancer.

6. True or false: If you only occasionally perform fluoroscopy in the OR radiation protection equipment is uncomfortable and unnecessary.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree