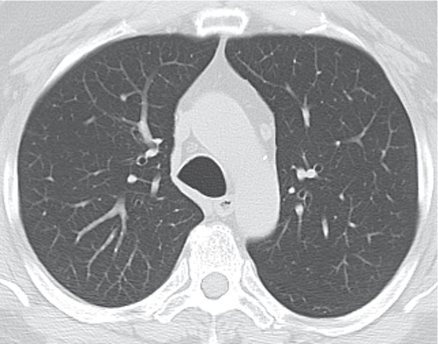

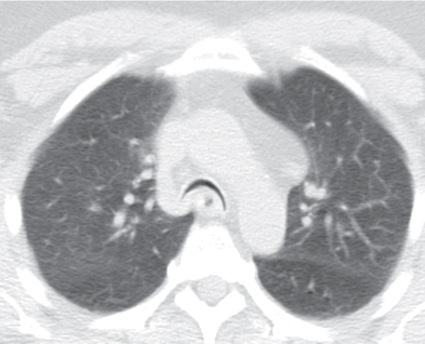

CASE 20 64-year-old man presenting with chronic cough and recurrent respiratory infections Paired end-inspiratory (Fig. 20.1) and dynamic-expiratory (Fig. 20.2) chest CT (lung windows) acquired at the aortic arch. End-inspiratory CT (Fig. 20.1) shows a slightly dilated, ovoid tracheal morphology. Dynamic-expiratory CT (Fig. 20.2) reveals near total collapse of the trachea with a crescentic frown-like appearance (frown sign) Tracheomalacia; confirmed at bronchoscopy None Tracheomalacia (TM) is undetectable and therefore under-diagnosed on routine end-inspiratory imaging. The normally more compliant posterior membranous tracheal wall is displaced to a greater degree than the less compliant cartilaginous anterolateral walls during forced expiration or coughing. TM is characterized by excessive expiratory collapse of the tracheal walls and/or supporting cartilage and is an important cause of airway obstruction, chronic cough, recurrent lung infection, and other respiratory symptoms. Although most cases of acquired TM diffusely involve the intrathoracic trachea, TM may also be localized. If the main-stem bronchi are also involved, the term tracheobronchomalacia (TBM) is used. Bronchomalacia (BM) is isolated weakness and collapsibility of one or both mainstem bronchi without tracheal involvement and is less common. Fig. 20.1 Fig. 20.2 (Images courtesy of Philip Boiselle, MD, Harvard Medical School and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts.) TM is divided into congenital (primary) and acquired (secondary) forms of disease. TM is the most common congenital anomaly of the trachea. It can occur as an isolated finding in healthy infants, but is more commonly seen in premature infants as a consequence of immature tracheobronchial cartilage. Primary TM may also be associated with tracheoesophageal fistula and vascular rings. Other forms of primary disease result from an abnormal tracheal cartilaginous matrix and include polychondritis, chondromalacia, and various mucopolysaccharidoses (e.g., Hunter and Hurler syndrome). Further discussion of congenital or primary TM is beyond the scope of this textbook. An additional congenital condition, although some authorities contend it is acquired, found in adults, is tracheomegaly (aka Mounier-Kuhn syndrome). This rare condition is characterized by atrophy of longitudinal elastic fibers and thinning of the muscularis mucosa (see Case 19). Acquired or secondary TM is more common than congenital TM and caused by degeneration of normal cartilaginous support. A variety of entities can cause secondary TM in adults, including prior prolonged intubation, tracheotomy, tracheostomy, antecedent tracheal surgery, lung transplantation, recurrent tracheobronchitis, external tracheal compression from various structures (e.g., thyroid mass or goiter, aberrant vasculature, aneurysmal dilatation of great vessels, left atrial and/or left atrial appendage enlargement, mediastinal tumors), mediastinal radiation therapy, chest wall musculoskeletal deformities (e.g., scoliosis, pectus excavatum), severe emphysema, etc. Antecedent tracheostomy or endotracheal tube intubation is the most common cause of secondary TM. Additionally, chronic inflammation and irritants, such as cigarette smoke, are important contributors to the development of TM.

Clinical Presentation

Clinical Presentation

Radiologic Findings

Radiologic Findings

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Discussion

Discussion

Background

Etiology

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree