Vascular |

Portal hypertension

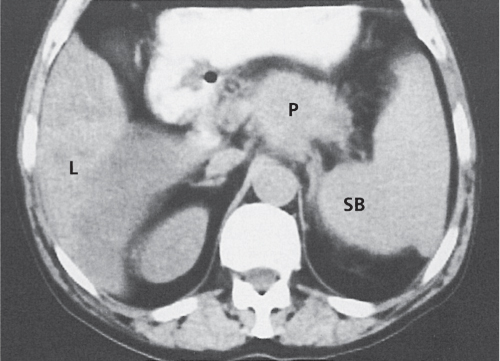

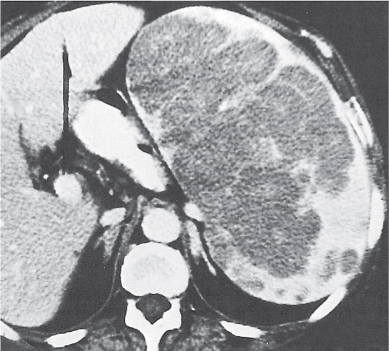

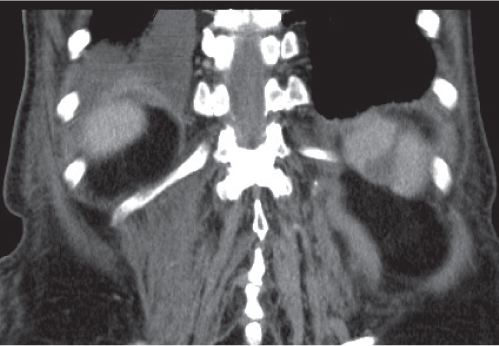

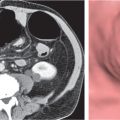

Fig. 21.3 |

Splenomegaly associated with liver cirrhosis and ascites, as well as abdominal and/or retroperitoneal venous collaterals.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (portal venous phase [PVP], parenchymal phase [PP]).

PVP: Optimal contrast of splenic and portal veins.

PP: Optimal phase to assess venous collaterals.

Diagnostic pearls: Splenomegaly, liver cirrhosis, ascites, enlarged portal vein, and numerous venous collaterals. |

Common causes of portal hypertension include liver cirrhosis, pancreatic disease with portal obstruction, and portal vein thrombosis. Biphasic CT (especially PVP) important to assess portal vessels and venous collaterals. |

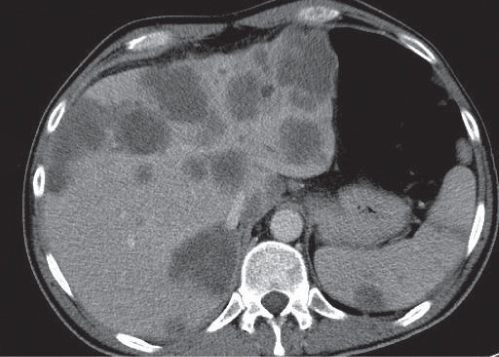

Splenic infarct

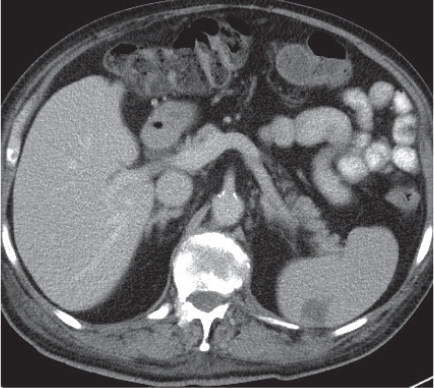

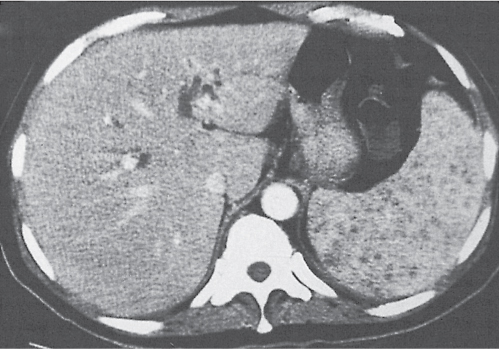

Fig. 21.4 |

Segmental to global ischemia of the spleen due to vascular occlusion.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Nondiscernible from parenchyma. Calcifications may develop in chronic stages.

PP: Wedge-shaped, nonattenuating peripheral parenchymal defect (s).

Base typically abuts the splenic capsule, apex points toward the hilum.

Diagnostic pearls: Wedge-shaped, nonattenuating peripheral parenchymal defect (s). |

Acute infarction mainly caused by arterial emboli (atherosclerosis, atrial fibrillation, and aortic valve). Renal infarction often concomitant. Chronic infarction due to vascular (aneurysm, splenic vein thrombosis) and hematological (sickle cell anemia/leukemia, hypercoagulable states) reasons, splenic torsion, vessel infiltration (tumors, abscesses), as a complication of AIDS, chemotherapy, and chemoembolization (TACE) of the liver.

Global infarction results in hypoattenuation of the spleen with or without hyperattenuating cortical rim (capsule). |

Splenic vein thrombosis (SVT)

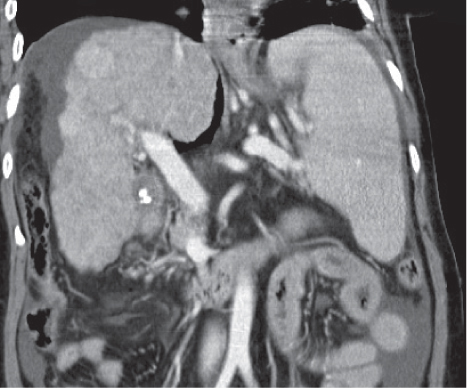

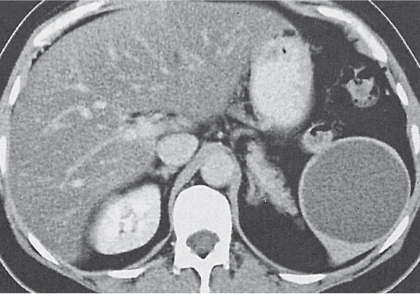

Fig. 21.5 |

Nonspecific splenomegaly associated with nonenhancing (clotted) splenic vein.

Scan recommendation:

Multiphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PVP, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Clotted vein usually not discernible from normal vessel. Calcifications in chronic stages.

PVP: Nonattenuation of splenic vein.

PP: Marked abdominal and retroperitoneal collaterals.

Diagnostic pearls: Marked abdominal and retroperitoneal collaterals and nonenhancing (clotted) splenic vein. |

Acute SVT may extend only up to the branching of the superior mesenteric vein, whereas chronic SVT usually is associated with portal vein thrombosis. On precontrast scans, fresh clot may appear hyperdense as compared with vessel walls. |

Inflammation |

Sarcoidosis

Fig. 21.6 |

Splenomegaly with multiple hypodense lesions.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Hypodense parenchymal noduli of varying size (4 mm to 10 cm).

PP: Sometimes discrete patchy enhancement of noduli, most often no enhancement.

Diagnostic pearls: Enlarged periaortic and retrocrural lymph nodes and associated splenomegaly are seen with low-attenuation lesions on postcontrast scans. |

Eleven to 42% of patients with sarcoidosis develop splenomegaly. Typically associated with abdominal, thoracal, and mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Patients with splenic sarcoidosis always also have pulmonary sarcoidosis.

CT can only display (rare) focal lesions but not a (more common) diffuse splenic infiltration. Differential diagnosis: septicemia, tuberculosis (TB), micronodular metastases, Gaucher disease, and amyloidosis. |

Congenital |

Polysplenia |

Ectopic splenic tissue, predominantly in the hilus region of the spleen.

Scan recommendation:

Contrast-enhanced CT (PP), although ultrasound may suffice for diagnosis.

Diagnostic pearls: Numerous small splenic, preferentially right-sided masses, bilateral distribution of usually left-sided visceral organs, and intrahepatic termination of the inferior vena cava (IVC) with continuation via the azygos vein. |

Polysplenia in combination with left isomerism is called polysplenia syndrome. It is a rare anomaly, often associated with cardiovascular malformation, gastrointestinal (GI) malrotation, preduodenal portal vein, anomalous liver, and absence of a suprarenal vena cava. Asplenia and polysplenia syndrome may be pathogenetically related. Absence of a normalsized spleen is a criterion to differ from patients with accessory spleens. |

Accessory spleen (splenosis)

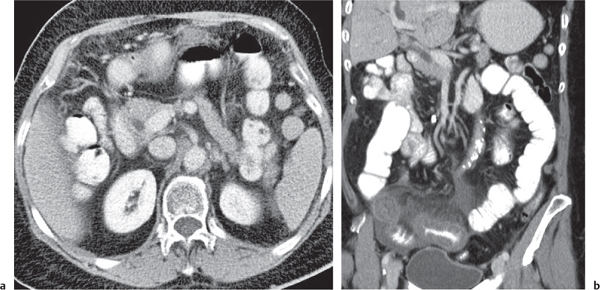

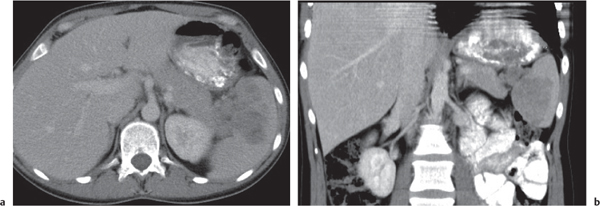

Fig. 21.7a, b |

Multiple, usually small spleens, predominantly left-sided, but often also bilateral.

Scan recommendation:

Contrast-enhanced CT (PP), although ultrasound may suffice for diagnosis.

Diagnostic pearls: Small, round nodules near the splenic hilum with same texture and contrast enhancement as for a normally sized and located spleen. |

Asymptomatic accidental finding in 10% to 30% of patients. May hypertrophy after splenectomy. Embryogenetically, a failure of splenic buds to unite within dorsal mesogastrium.

Presence of a normal-sized spleen is a criterion to differ from patients with polysplenia (syndrome). |

Congenital cyst

Fig. 21.8 |

Unilocular, homogeneous, cystic lesion of the spleen.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Water-density lesion with pencil-thin margins occasionally calcified. Hemorrhagic and protein-rich cysts may also be hyperdense as compared with normal spleen.

PP: Usually nonenhancing. Contrast enhancement indicative of an infection.

Diagnostic pearls: Well-defined, round cystic splenic lesion with water density. |

Cysts may be congenital or acquired. Congenital cysts have a secreting inner (endothelial) lining. Differential diagnosis comprises abscesses (granulomatous, fungal, pyogenic, and parasitic), infarction, peliosis, hemangioma, lymphangioma, metastases (pancreatic, ovarian, and melanoma), and lymphoma. |

Trauma |

Subcapsular hematoma

Fig. 21.9 |

Crescent or lenticular splenic lesion in subcapsular location that flattens or indents the surface of the spleen. Density depends on stage of hemorrhage.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenchanced CT: High- (acute) or low-density (subacute/chronic), sharply demarcated from adjacent normal splenic tissue.

PP: Better delineation of extent of hematoma.

Diagnostic pearls: In a patient with a history of trauma, characterized by hypo- to hyperdense, non-enhancing crescent lesion in subcapsular location. |

Layered appearance of hematomas typically observed in subacute/chronic stages due to different maturation of blood products after sequential bleedings.

Gas bubbles are a sign of secondary infection. Peri-/intrasplenic CM excretion indicative of traumatic vessel laceration. Chronic hematomas may calcify later. Subcapsular hematoma in combination with rupture of the splenic capsule may lead to life-threatening intra-abdominal bleeding. |

Splenic laceration

Fig. 21.10 |

Cleft defect through the spleen associated with perisplenic blood.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Cleft defect as linear hypodensity partially or globally traversing the spleen. Concomitant hematoma may be high- (acute) or low-attenuating (subacute/chronic), depending on stage.

PP: Cleft remains hypodense, but usually better delineation of extent of laceration is seen.

Diagnostic pearls: Hypodense, nonenhancing cleft defect interrupting splenic margin (s), associated with perisplenic blood (hemoperitoneum). |

Splenic laceration typically is associated with perisplenic blood (hemoperitoneum). If only the bare area of the spleen is involved, blood usually flows via the splenorenal ligament into the left anterior pararenal space and thus cannot be detected by peritoneal lavage.

On postcontrast scans, hyperdense acute hematoma may be masked by hyperdense splenic parenchyma. An intraparenchymal hematoma may later develop into a pseudocyst.

Treatment: usually “no touch” approach. Bleeding may compress itself. |

Posttraumatic pseudocyst

Fig. 21.8 , p. 713 |

Typical late effect of an intraparenchymal hematoma.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Clearly demarcated water-density (< 20 HU) lesion occasionally with a calcified rim. Intracystic blood clots may appear hyperdense.

PP: Nonenhancing.

Diagnostic pearls: Clearly defined, nonenhancing, water-density cystic splenic lesion with a calcified rim. |

Effect of cystic degeneration of splenic hematoma. More common than congenital cysts.

CT findings are identical to congenital cyst (Fig. 21.8 , p. 713). Hemorrhagic cysts often calcify. |

Infection |

Hydatid cysts |

Large uni- or multilocular, well-defined, near-water-density cyst.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Near-water-density lesion (10–45 HU), often with curvilinear, ringlike (hyperdense) calcifications. Daughter cyst may appear slightly hypodense as compared with mother cysts.

PP: Enhancement of cyst wall and septations.

Diagnostic pearls: Multilocular, clearly defined, water-density, enhancing cysts with ringlike, curvilinear calcifications. |

The most common parasite of splenic hydatid cysts is Echinococcus granulosus. Usually the liver is involved. May appear multiloculated and may contain intracystic calcification.

Search for concomitant parasitic cysts in the liver and peritoneal cavity.

Differential diagnosis: Hydatid cysts typically show a strong rim enhancement on postcontrast scans. |

Abscess

Fig. 21.11 |

Unilocular (70%), sometimes multilocular (30%), liquefied pus collection within liver parenchyma.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Hypodense, ill-defined parenchymal lesion.

PP: No or peripheral rim enhancement.

Diagnostic pearls: Enlarged spleen with singular or multiple ill-defined, hypodense, coalescing micronodular lesions.

Look out for concomitant liver lesions. |

Particularly observed in immunocompromised patients; otherwise rare. Common causative organisms are Candida, Pneumocystis carinii, and mycobacteria.

May result from previous endocarditis. Often concomitant abscesses in the liver and kidneys.

Gas bubbles are evidentiary but rare.

Multilocular abscesses may show cluster sign similar to a hepatic abscess.

Micronodular lesions are pathognomonic for fungal abscesses due to microvascular occlusions. |

Splenitis |

Poorly defined low-density mass in the spleen. |

Rare complication of sepsis. May cause spontaneous splenic rupture. |

Granulomatous infection

Fig. 21.12 |

Splenomegaly with scattered punctate, low-attenuation lesions.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Multiple hypoattenuating lesions.

PP: Usually lesions are nonenhancing.

Diagnostic pearls: Enlarged abdominal lymph nodes, ascites, and presence of multiple low-density lesions on pre- and postcontrast scans in the liver and spleen. |

Typically associated with abdominal and thoracal lymphadenopathy. Splenomegaly is almost always present. Calcifications represent healed infection with TB, pneumocystic pneumonia, or histoplasmosis. Differential diagnoses: sarcoidosis, peliosis, micronodular metastases, and TB. |

Neoplasms |

Benign neoplasms |

Hemangioma |

Rare, but the most common primary benign neoplasm of the spleen.

Scan recommendation:

Multiphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, hepatic arterial phase [HAP], PVP, PP, delayed phase [DP]).

Nonenhanced CT: Usually well-circumscribed masses isodense to blood.

HAP: Early peripheral global or nodular enhancement. PP: Progressive centripetal filling usually isodense to blood.

DP: Persistent global enhancement that stays isodense with blood.

Diagnostic pearls: Peripheral globular enhancement on HAP scans and progressive centripetal filling in subsequent scans (flash filling). |

Predominantly cystic lesions in the spleen that may contain speckled calcifications. No gender preference; peak age: 35 to 65 y. Hemangiomas usually are isodense to blood and thus show a similar enhancement pattern as the aorta.

May be part of Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome, a generalized angiomatosis, including port wine–colored cutaneous hemangiomas, hemangiomas of the bowel and soft tissue, superficial venous varicosis, and unilateral bony hypertrophy of one extremity. Lesions may contain curvilinear calcifications. |

Lymphangioma |

Rare malformations consisting of multiple endothelium-lined cysts containing lymphatic fluid.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Isodense to splenic parenchyma.

PP: Discrete rim enhancement.

Diagnostic pearls: Multiple low-density, low-enhancing, sharply marginated, thin-walled cysts, predominantly in a subcapsular location. |

Lesions of childhood.

The size of the lymphatic spaces varies from capillary to cavernous and cystic.

Lesions may contain curvilinear calcifications.

Rim enhancement is due to discrete enhancement of the lesion’s wall.

Differential diagnoses: histoplasmosis, TB, and micronodular hemangiomas. |

Hamartoma

Fig. 21.13 |

Usually single, spherical, predominantly solid mass lesions, but cysts may occur.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Hypo- to isodense to spleen.

PP: Variable from no attenuation to slight attenuation, but usually uniform.

Diagnostic pearls: Imaging findings are nonspecific. |

Rare. Hamartomas contain a mixture of normal and abnormal splenic tissue. Fatty components and amorphous calcifications are observed. |

Malignant neoplasms |

Angiosarcoma

Fig. 21.14 |

An ill-defined, inhomogeneous, hypervascular mass composed of cystic and solid components.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Variable density (cystic/solid components).

PP: Variable enhancement.

Diagnostic pearls: Several ill-defined, inhomogeneous, hypervascular, splenic and hepatic masses in patients with known exposition to Thorotrast. |

Rare primary malignancy of the spleen, directly associated with Thorotrast exposure. Also occurs in liver, lung, brain, bones, and lymph nodes. First symptoms of disease often are fever, malaise, ascites, hepatosplenomegaly, anemia, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia. Angiosarcomas grow rapidly and metastasize early. Poor prognosis: most patients die within 1 y after onset of symptoms. |

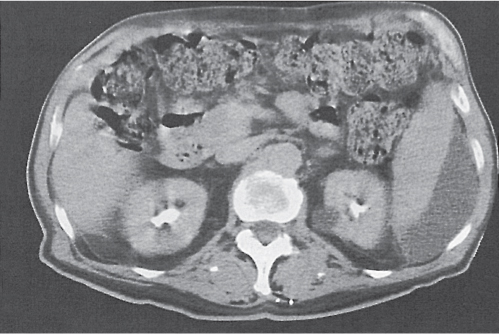

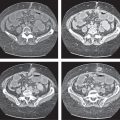

Lymphoma

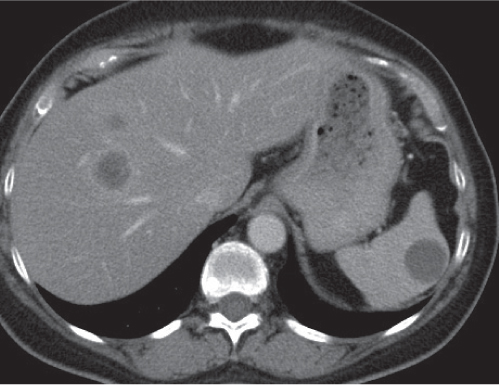

Fig. 21.15a, b |

Most common malignant neoplasia of the spleen. May be focal (lesions > 10 mm) or diffuse (typical). Always comes with a distinctly enlarged spleen.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Focal lesions may sometimes be hypodense as compared with normal spleen parenchyma. Usually isodense (as in diffuse disease). PP: Iso-/hypodense to spleen.

Diagnostic pearls: Splenomegaly with or without hypodense, nonenhancing lesions seen in patients with known lymphoma. |

Splenic involvement observed in both Hodgkin disease and non–Hodgkin lymphoma.

In Hodgkin disease, spleen considered as “nodal”; in non–Hodgkin lymphoma, as “extranodal” organ. Moderate splenomegaly is nondiagnostic of splenic involvement in Hodgkin disease. Even a normal-sized spleen may harbor lymphoma.

AIDS-related lymphoma often presents as focal lesions. |

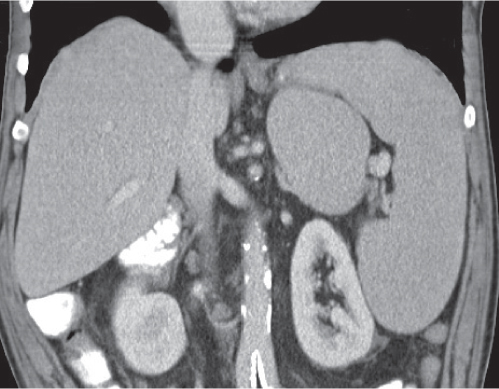

Metastasis

Fig. 21.16 |

Very unspecific: either solitary or multiple, cystic or solid.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Solid metastases usually isodense; cystic metastases slightly hypodense as compared with normal spleen parenchyma.

PP: Variable, central to peripheral to no enhancement.

Diagnostic pearls: Unspecific but uniformly contrasting lesions with splenic and abdominal involvement in a patient with a known history of cancer. |

Rare. The most common primaries (in decreasing frequency) are breast (20%), lung (21%), ovarian (9%), melanoma (7%), and prostate (5%). Typically, metastases are implanted in the spleen via hematogenous spread.

The presence of calcifications almost excludes metastatic spread (exception: very rarely mucinous tumors of the stomach and colon).

Cystic metastases observed particularly in ovarian carcinoma and sometimes melanoma. Biopsy is the method of choice for further diagnosis. |

Leukemia |

Spleen may be enlarged but usually has homogeneous, normal attenuation values (40–50 HU).

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Physiological attenuation of splenic parenchyma. Blood within vessels sometimes appears hypodense compared with vessel wall.

Diagnostic pearls: Splenomegaly in a patient with known leukemia. |

Spontaneous rupture of leukemic spleen occurs.

A normal-sized spleen does not exclude splenic involvement.

Different types of leukemia are not predictable from CT scans.

Lymphadenopathy may be indicative, but otherwise absence does not exclude leukemia.

Differential diagnoses: extramedullary hematopoiesis, other causes of splenomegaly. |

Other |

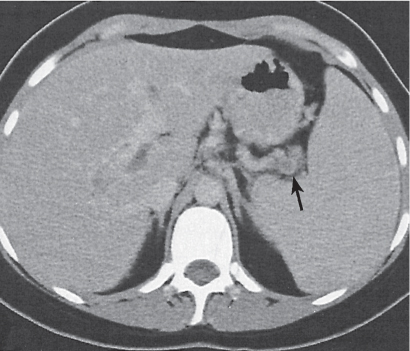

Pancreatic pseudocyst

Fig. 21.16 |

A pancreatic pseudocyst may be mistaken for a cystic mass of the spleen.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Hypo- to isodense.

PP: Marked abdominal and retroperitoneal collaterals. |

History or imaging evidence of past acute pancreatitis may be obtainable. |

Splenomegaly

Fig. 21.17 |

Increased spleen volume (splenic index > 500 cm3).

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Variable. Density normal in congestive disease, extramedullary hematopoiesis and hemochromatosis.

Low-attenuation in all other storage diseases. High attenuation in hemosiderosis.

PP: Variable, depending on underlying cause.

Diagnostic pearls: Enlarged spleen with convex medial border. Low attenuation typical for storage diseases, high attenuation for hemosiderosis. |

CT appearance depending on underlying cause of splenomegaly: congestive disorders (e.g., portal vein occlusion, portal hypertension, and sickle cell anemia), extramedullary hematopoiesis; storage disorders (amyloidosis, primary hemochromatosis, and Gaucher disease), hemosiderosis, space-occupying lesions (cysts, neoplasms, and abscesses), and trauma (e.g., hematoma). Splenomegaly in combination with pancytopenia is termed hypersplenism. |