Vascular |

Varices

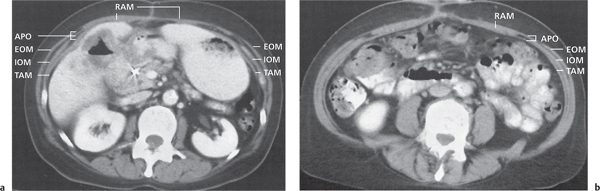

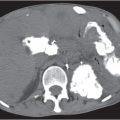

Fig. 23.2a, b |

Increased number and size of venous vessels in the subcutaneous fatty tissue.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, portal venous phase [PVP], parenchymal phase [PP]).

Nonenhanced CT: Subcutaneous vasculature, isodense to other vessels.

PVP: Portal venous hypertension with recanalization of the umbilical vein and dilated paraumbilical veins (caput medusae).

PP: Typical venous enhancement. |

Main cause of abdominal wall varices is an occlusion of the central venous system in the abdomen, pelvis, or chest. Location of collateral vessels indicative of the most likely site of the obstruction. |

Hernias |

Paraumbilical hernia

Fig. 23.3 |

Ventral hernia near the umbilicus, filled with mesenteric fat with or without loops of bowel.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Control scan for PP (calcifications, etc.).

PP: Best visualization of mesenteric vessels.

Diagnostic pearls: Oral and rectal contrast is important to better differentiate bowel lumen. In children, preferably nonenhanced CT (radiation/contrast medium). |

Acquired hernia in adults due to separation of the rectus abdominis muscle. Secondary to obesity, multiple pregnancies, or other causes of increased abdominal pressure. Differential diagnosis: umbilical hernia. |

Umbilical hernia

Fig. 23.4 |

Ventral hernia straight through the umbilicus, filled with mesenteric fat with or without loops of bowel.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Only necessary as a control for hyperattenuating findings on PP scans (calcifications, etc.).

PP: Best phase for visualization of mesenteric vessels.

Diagnostic pearls: Oral and rectal contrast is important to better differentiate bowel lumen. In children, preferably nonenhanced CT (radiation/contrast medium). |

Acquired hernia in infants. Herniation through a weak umbilical scar. Usually resolves during childhood. |

Epigastric/hypogastric hernia |

Midline hernia, either between the umbilicus and the xiphoid process (epigastric) or below the umbilicus (hypogastric), filled with mesenteric fat with or without loops of bowel.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Only necessary as a control for hyperattenuating findings on PP scans (calcifications, etc.).

PP: Best phase for visualization of mesenteric vessels.

Diagnostic pearls: Oral and rectal contrast important to better differentiate bowel lumen. In children, preferably nonenhanced CT (radiation/control medium). |

Acquired hernia in adults due to separation of the rectus abdominis muscle. Secondary to obesity, multiple pregnancies, or other causes of increased abdominal pressure. |

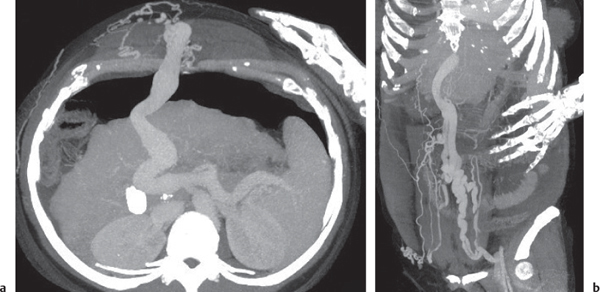

Incisional hernia

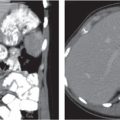

Fig. 23.5 |

Ventral hernia following abdominal wall incision and filled with mesenteric fat with or without loops of bowel.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Only necessary as a control for hyperattenuating findings on PP scans (calcifications, etc.).

PP: Best phase for visualization of mesenteric vessels.

Diagnostic pearls: Oral and rectal contrast is important to better differentiate bowel lumen. In children, preferably nonenhanced CT (radiation/contrast medium). |

Delayed complication in ~4% of abdominal operations. Usually occurs within first 16 weeks after surgery. |

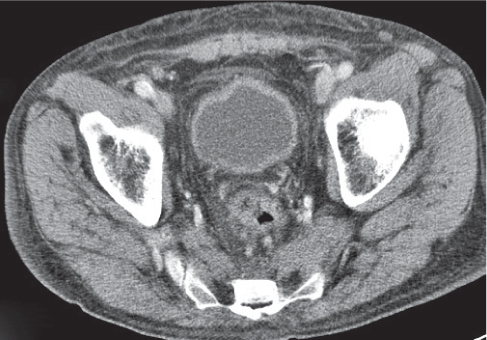

Spigelian hernia

Fig. 23.6 |

Paramedian infraumbilical herniation of mesenteric fat with or without loops of bowel between the internal and external oblique muscles.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Only necessary as a control for hyperattenuating findings on PP scans (calcifications, etc.).

PP: Best phase for visualization of mesenteric vessels.

Diagnostic pearls: Herniation of bowel loops between the internal and external oblique muscles below the navel with a narrow hernia neck with or without signs of an abdominal ileus (incarceration). |

Spigelian hernias occur spontaneously or postoperatively. They represent < 2% of ventral abdominal hernias. Herniation occurs through the fascia below the level of the navel, lateral to the junction of the linea semilunaris (i.e., lateral margin of the rectus muscle sheath) and the arcuate line.

The contents of the hernia characteristically lie between the internal and external oblique muscles. The hernia neck may be narrow, and incarceration of bowel loops is not uncommon. |

Inguinal hernia

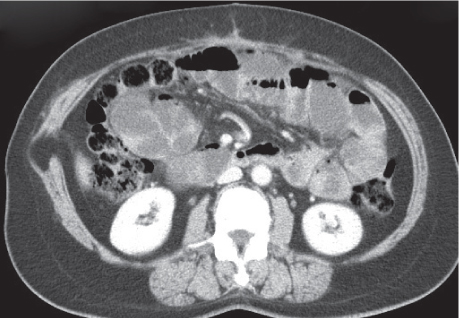

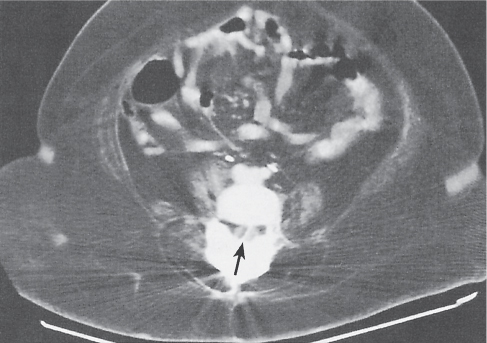

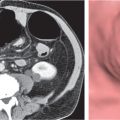

Fig. 23.7 |

Herniation of mesenteric fat with or without loops of bowel into the inguinal canal.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Only necessary as a control for hyperattenuating findings on PP scans (calcifications, etc.).

PP: Best phase for visualization of mesenteric vessels.

Diagnostic pearls: The neck of a direct hernia lies medially and the neck of an indirect hernia lies laterally to the inferior epigastric vessels. |

Inguinal hernias may be either direct or indirect. Direct hernias protrude via the Hesselbach triangle and usually extend into the scrotum or the labium majus. Indirect hernias pass via the internal inguinal ring along the inguinal canal and protrude through the external inguinal ring. Complete hernias may extend into the scrotum (along spermatic cord) or labium majus. |

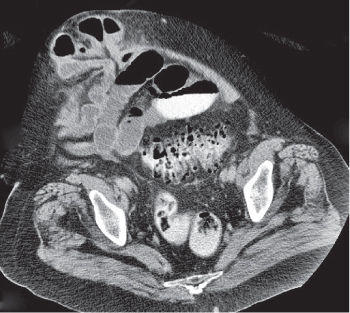

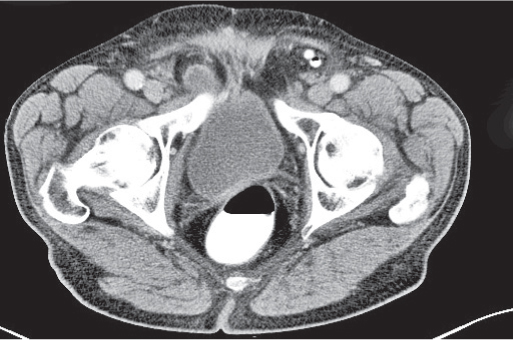

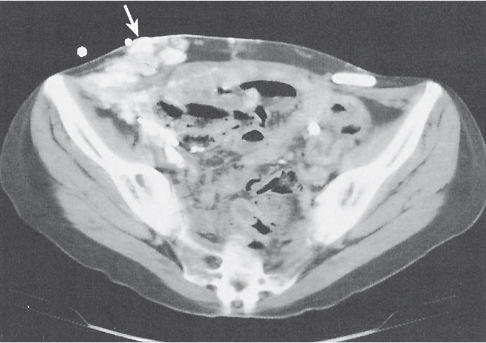

Femoral hernia

Fig. 23.8 |

Herniation of mesenteric fat with or without loops of bowel medially to the inguinal canal.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Only necessary as a control for hyperattenuating findings on PP scans (calcifications, etc.).

PP: Best phase for visualization of mesenteric vessels.

Diagnostic pearls: The neck of a direct hernia lies medially and the neck of an indirect hernia lies laterally to the inferior epigastric vessels. |

Femoral hernias protrude medially to femoral vessels, anteriorly to the pubic ramus, and posteriorly to the inguinal ligament. They occur predominantly in women (~70%) and are significantly more prone to bowel strangulation than inguinal hernias. The Richter hernia is a subentity, containing only a small portion of antimesenteric bowel circumference. |

Obturator hernia |

Herniation of bowel loops between obturator and pectineus muscles.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Only necessary as a control for hyperattenuating findings on PP scans (calcifications, etc.).

PP: Best phase for visualization of mesenteric vessels.

Diagnostic pearls: Bowel loop interposed between obturator (posteriorly) and pectineus (anteriorly) muscle. |

Typically occurs in elderly women due to a laxity in or defect of the pelvic floor. Obturator hernias have a right-sided preference, thus predominantly contain small bowel loop, such as the ileum. |

Lumbar hernia |

Dorsolateral herniation of mesenteric fat, bowel loop with or without kidneys.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Diagnostic pearls: Superior lumbar herniation (SLH) through the lumbar triangle of Grynfeltt–Lesshaft, inferior lumbar herniation (ILH) through the triangle of Petit. |

Rare acquired hernia in the flank region, usually between ages 50 and 70 y.

SLH occurs through the lumbar triangle of Grynfeltt–Lesshaft, which is bordered by the 12th rib, internal oblique muscle, and paraspinous muscles. ILH occurs through the lumbar triangle of Petit, which is bordered by the iliac crest, external oblique muscle, and latissimus dorsi muscle. |

Infection/inflammation |

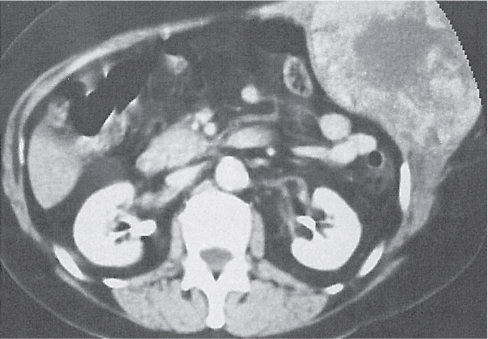

Abscess

Fig. 23.9 |

Sharply defined near-water-density fluid collections, often surrounded by a capsule.

Scan recommendation:

Multiphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Well-defined, round lesions, denser than subcutaneous fatty tissue, but less dense than abdominal wall musculature.

PP: Distinct enhancement of capsule and septa. No enhancement of central portion (necrosis). |

Gas or gas–fluid level is seen in only 30% of abdominal wall abscesses. Over time smaller lesions may aggregate into a single large cavity. May result from a direct route of an intra-abdominal process such as Crohn disease, diverticulitis, appendicitis, and perforated neoplasms.

Typical postoperative complication.

PAD is the usual treatment of choice, followed by surgical excision. |

Cellulitis/phlegmon

Fig. 23.10 |

Diffuse but localized inflammation of the subcutaneous fatty tissue with or without involvement of muscle sheets and/or peritoneal fascia.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Ill-defined hyperdensity of the subcutaneous fatty tissue with or without involvement of underlying muscles/fascia.

Diagnostic pearls: Ill-defined localized hyperdensity of the subcutaneous fatty tissue in patients after surgery or skin injury. |

Most commonly resulting from a postsurgical, posttraumatic wound infection. By definition, lacking gas or fluid.

Treatment often protracted: intravenous (IV) antibiotics with or without surgical exposure. |

Necrotizing fasciitis |

Extensive necrosis of subcutaneous tissues and fascia.

Scan recommendation:

Multiphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Loss of conspicuity of fascial layers and increased density of fatty tissue.

PP: Distinct enhancement of fatty tissue and fascial layers.

Diagnostic pearls: Diffusely increased density of fatty tissue and subtle subcutaneous gas collections (lung window). |

Characteristic complication of necrotizing pancreatitis. Subcutaneous gas collections are common. |

Edema

Fig. 23.11 |

Streaky opacities of fluid density in the subcutaneous tissue.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Symmetrical but diffuse fluid-density congestion of subcutaneous fatty tissue with or without underlying muscles/fascia. |

Causes for subcutaneous edema include heart failure, hypoproteinemia, and various other systemic diseases. |

Congenital |

Muscular atrophy

Fig. 23.12 |

Diffuse muscular atrophy affects several muscle groups on both sides of the midline. Focal atrophy usually is unilateral and restricted to a single muscle group.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Atrophic muscles decreased in size and density (due to an increased fat content).

PP: Atrophic muscles appear hypodense compared with normal musculature. |

Diffuse muscular atrophy usually is associated with congenital or acquired neuromuscular disease.

Focal atrophy typically is a delayed complication of transverse or subcostal abdominal incision, probably due to a denervation injury. Focal and diffuse atrophy may both cause disappearance of whole muscle layers on CT scans. |

Trauma |

Hematoma |

Round or spindle-shaped mass, usually in the rectus sheath or subcutaneous tissue.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Iso- to hyperdense to muscles, depending on stage.

PP: No additional information.

Diagnostic pearls: A nonenhancing, hyperdense mass on precontrast scans. Density of the lesion decreases and approaches that of plain serum after 2 to 4 weeks. |

May occur spontaneously due to muscle strain or secondary to trauma, surgery, or anticoagulation.

Seat-belt injuries may lead to abdominal wall disruption, resulting in a transverse tear of the rectus muscle. Associated hemorrhage thus is not confined to the rectus sheath. Chronic hematoma often shows sedimentation of hyperdense iron particles. Hematoma may cross the midline below but not above the arcuate line. |

Trapped air |

Gas bubbles within subcutaneous fatty tissue, muscles, or fascial layers.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Small, low-attenuating gas bubbles.

PP: No additional information. |

May result from penetrating injury of the abdominal wall, thoracic injuries, forced ventilation, or aerogenous germs. |

Rhabdomyolysis |

Excessive release of myoglobin from traumatic, ischemic, or toxic damaged muscle.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Sometimes focal hypodense areas within affected muscle.

PP: Affected areas remain hypodense. |

Typical causes include severe soft tissue injury, surgical interventions, and compartment syndrome. Other causes are medications (neuroleptica, statins, cocaine, and propofol), malignant hyperthermia, alcohol intoxication, autoimmune reactions, inflammation, and muscle infection. Rhabdomyolysis often causes renal failure (crush syndrome). |

Benign neoplasms |

Lipoma |

Smooth encapsulated fatty mass within subcutaneous fatty tissue, abdominal muscles, or adjacent tendon sheaths.

Scan recommendation:

Multiphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Isodense to subcutaneous fat.

PP: No enhancement.

Diagnostic pearls: Easy to diagnose in nonfatty tissue. Often invisible in subcutaneous fat. |

A fat-containing spigelian hernia may mimic lipoma of the abdominal wall.

It is often possible to indirectly visualize lipomas within the subcutaneous fatty tissue by considering the space-occupying effect of the lesions in the form of side differences in the outer shape of the abdominal wall. |

Hemangioma |

Well-enhancing vascular mass in the subcutaneous or muscular tissue.

Scan recommendation:

Multiphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, arterial phase [HAP], PP, delayed phase [DP]).

Nonenhanced CT: Usually well-circumscribed masses isodense to blood.

AP: Early peripheral global or nodular enhancement.

PP: Progressive centripetal filling isodense to blood.

DP: Persistent global enhancement that stays isodense with blood.

Diagnostic pearls: Peripheral globular enhancements on AP scans and progressive enhancement during following contrast phases. Hemangiomas usually show a similar enhancement pattern as the aorta. |

Histologically, a benign neoplasm of thin, fibrous stroma that surrounds multiple vascular channels lined by a single layer of endothelial cells.

Large hemangiomas appear heterogeneous and may contain a central fibrotic cleft of low density. May contain calcified phleboliths. |

Neurofibroma |

Usually multiple round soft tissue masses in the subcutaneous tissue of the abdominal wall.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Isodense to abdominal wall musculature.

PP: Iso- to hyperdense compared with muscles.

Diagnostic pearls: Peripheral globular enhancements on AP scans and progressive enhancement during following contrast phases. Hemangiomas usually show a similar enhancement pattern as the aorta. |

Neurofibromas mainly lie within the subcutaneous fatty tissue of patients with neurofibromatosis. In some patients, they may be found within the musculature.

Spinal involvement or long plexiform neurofibromas of peripheral nerves may also be apparent on CT. CT usually is performed for staging. |

Sebaceous cyst |

Well-defined, fluid-density mass in the subcutaneous tissues.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Hypo- to isodense to abdominal wall musculature.

PP: No enhancement. |

Slow-growing benign mass, usually asymptomatic. |

Tumoral ossification

Fig. 23.13 |

Well-defined, calcified conglomerates within soft tissue.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Hyperdense (calcified) compared with all other tissues of the abdominal wall.

PP: No enhancement. |

May occur anywhere in the body. A rare occurrence in the abdominal wall. |

Malignant neoplasms |

Soft tissue sarcoma

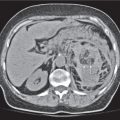

Fig. 23.14 |

Ill-defined, inhomogeneous mass, often containing areas of hemorrhage or necrosis.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Ill-defined, inhomogeneous mass.

PP: Only nonnecrotic areas enhance after contrast injection.

Diagnostic pearls: Ill-defined heterogeneous mass with inhomogeneous contrast enhancement. |

Rare in the abdominal wall. Local recurrence and distant metastases following surgical resection are common.

Diameter of metastases characteristically already measures several centimeters at the time of diagnosis. |

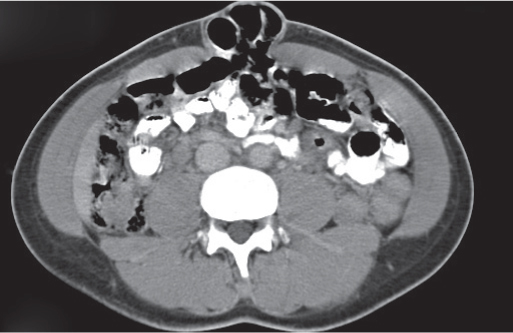

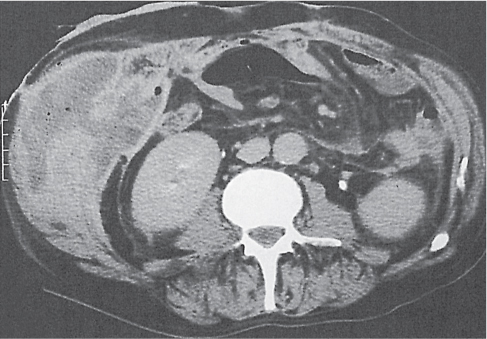

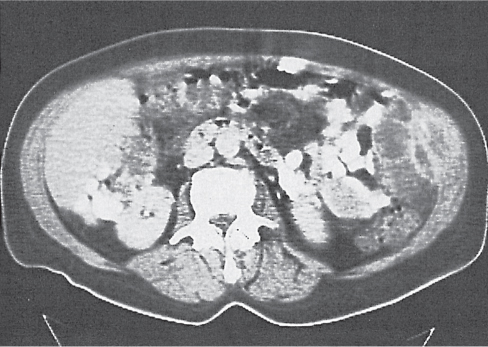

Lymphoma

Fig. 23.15 |

Diffuse, relatively low-attenuating infiltration of abdominal wall musculature.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Isodense to abdominal wall musculature. PP: Slightly hyperdense compared with muscle. |

Primary lymphoma of the abdominal wall is very rare; direct infiltration from an intra-abdominal origin is more common. |

Desmoid tumor |

Characteristically unilateral, well-defined, round or oval soft tissue mass.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Isodense to abdominal wall musculature.

PP: Enhances strongly.

Diagnostic pearls: Well-defined, round, strongly enhancing soft tissue mass, restricted to one side of the abdomen. |

Rare, locally invasive fibroblastic proliferation arising from the aponeurosis of abdominal muscles (i.e., aggressive fibromatosis).

Desmoid tumors measure between 5 and 15 cm in diameter, are restricted to one side of the body, are more common in women, do not metastasize, and frequently recur. The typical age peak is 23 to 40 y.

Twenty-nine percent of patients with Gardner syndrome develop desmoid tumors of the abdominal wall. |

Metastases |

Well-defined nodules in the subcutaneous tissue, skin, or muscles.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Iso- to hyperdense to muscles. Malignant melanoma metastases appear slightly inhomogeneous in texture.

PP: Iso- to hyperdense compared with muscles.

Diagnostic pearls: If malignant melanoma is suspected primary, check mesentery (originates from ectoderm) for further metastases. |

Exclusively hematogenous metastases.

Characteristic locus for metastases of malignant melanoma, but primary tumor itself may also look alike.

Other types are lung, breast, ovarian (endometriosis), and renal cell carcinoma. May also be iatrogenic due to previous surgery. |

Tumor extension per continuitatem |

Contiguous infiltration of abdominal muscles and adjacent soft tissue.

Scan recommendation:

Biphasic CT (nonenhanced CT, PP).

Nonenhanced CT: Isodense to abdominal wall musculature.

PP: Iso- to hyperdense compared with muscles. |

Neoplasms originating from superficial abdominal organs are prone to extend into the abdominal wall. Likely primaries include malignancies of the transverse colon, gallbladder, urinary bladder, liver, and omen-tum. May also develop within a scar due to previous surgery. |