36 Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis and its subcategories are systemic inflammatory diseases of the connective tissue. The immunological etiology and pathogenesis have been only partially clarified. The main manifestations are found primarily on the joints of the hand (carpal, metacarpophalangeal, and proximal interphalangeal joints) and in the corresponding joints of the foot. They develop later on the large joints and the cervical spine. Rheumatoid arthritis also affects the synovial membranes of the tendon sheaths and the bursae, as well as parenchymal organs. Dorsopalmar radiographs or Norgaard’s semisupinated oblique views of the hand serve as the basis of diagnostic imaging by providing indirect evidence of soft-tissue involvement, osseous collateral phenomena, and direct signs of arthritis. High-resolution ultrasonography (US) is well suited to demonstrate rheumatic tenosynovitis and ruptured tendons. Early stages of arthritis can be assessed with MRI, which directly visualizes the inflammation of all tissues involved. The current status of inflammatory activity can be estimated with signaltime curves in contrast-enhanced MRI. Furthermore, pannus can be demonstrated before a planned synovectomy.

Pathoanatomy and Clinical Symptoms

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA; synonym chronic polyarthritis [CP]) is a systemic inflammatory disease of the mesodermal tissue of immunopathologic etiology. It is manifested primarily in the joint synovium, but also affects tendon sheaths, bursae, blood vessels, eyes, serous membranes, and internal organs. Its pathogenesis has been only partially clarified.

In the most common genetic predisposition (HLADR4), inflammatory activity of the synovial tissues can be caused by immune complexes and sensitized T-Lymphocytes. These lead to chronic synovitis with synovial proliferation and plump, villous remodeling, i.e., pannus formation, which can be manifested as “tumorous” pannus. Occasionally, deposits and inclusions of fibrin can also be found. The inflammatory granulation tissue spreads from the joint recesses over the articular cartilage and invades the bone from the “bare” areas (marginal zones free of articular cartilage adjacent to the joint capsules) in the so-called pincer grip. Local hyperemia in the bone marrow and immobilization due to pain lead to periarticular osteopenia (collateral phenomenon). The subchondral bone plate is altered by decalcification and inflammatory bone destruction.

Approximately two-thirds of patients experience a typical course of disease. Following a prodromal stage, rheumatoid arthritis begins insidiously with symmetric, polyarticular involvement of the peripheral joints of the hand and the foot. Clinically, there is pain on movement and horizontal pressure pain on the hand and foot. A doughy swelling appears in the joints. On the hands, the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints are predominantly involved (Fig. 36.1). Later, atrophy of the interosseous muscles can appear. Articular malalignments, such as the button-hole and swan-neck deformities, and palmar subluxations and ulnar deviations are common in advanced disease. Stiffening of the joints in flexion is called claw hand. Morning stiffness is characteristic; patients feel pain in joints and muscles for longer than 30 minutes. They are also intolerant to cold. So-called rheumatic nodules are by no means obligatory. If they are present, the course of disease is described as nodular. The typical serology with positive rheumatoid factors, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and C-reactive protein (CRP) are found in 75% of cases.

In the so-called atypical course, rheumatoid arthritis begins acutely in one or several joints with a predilection for the large joints. The most important characteristics of both rheumatoid subcategories are summarized in Table 36.1.

Currently, the most common classifications follow the American Rheumatism Association (ARA) criteria ( Table 36.2 ) and the New York criteria ( Table 36.3 ). These criteria are listed according to their probability of presence (from highest to lowest). Polyarthritis is probably present when three criteria are fulfilled; the articular symptoms must last for at least six weeks. Polyarthritis is certain when five criteria are present. Classic polyarthritis exists when more than six criteria are present.

Typical Course | Atypical Course | |

Frequency | 60–67% | 33–40% |

Begin | Slow, insidious | Acute |

Affected areas | Polyarticular | Mono-/oligoarticular |

Special Forms of Rheumatoid Arthritis

Adult Still Syndrome

This polyarticular, systemic course of chronic polyarthritis is accompanied by swelling of the liver, spleen, and lymph nodes, high fever, leukocytosis, iridocyclitis, and polyserositis (pleuritis, pneumonitis, pericarditis), as well as polyarthralgia and myalgia. Rheumatoid factors are negative. Articular symptoms are often first seen at later stages of the disease, usually as symmetric polyarthritis.

Felty Syndrome

This includes variants of seropositive rheumatoid arthritis with strong activation of the lymphoreticular system, splenomegaly, and lymphadenopathy. Laboratory findings show leukopenia or granulocytopenia and thrombopenia.

Sjögren Syndrome

This autoimmune adult “exocrinopathy” occurs predominantly amongwomen in menopause. There is a decrease in tear and saliva secretion (xerophthalmia and xerostomia). Focal lymphocytic or plasma-cell infiltration can cause internal organs, particularly the large salivary glands, to swell. This combination of symptoms without articular involvement is referred to as sicca syndrome. The primary form, which can progress to B-cell lymphoma, is differentiated from the secondary form, which involves a combination of the sicca syndrome and rheumatoid arthritis or collagenosis.

Caplan Syndrome

This is a combination of pneumoconiosis with rheumatoid arthritis. Both the pneumoconiosis and the synovial disease apparently reflect a rheumatoid reaction of the mesodermal tissue.

Juvenile or Special Forms of Rheumatic Arthritis

Common features: As in adult polyarthritis, there is inflammatory proliferation of synovial tissue with the formation of thick, villous pannus. This pannus leads to destruction of the articular cartilage and pressure erosions in the bones. Rheumatoid nodes often appear in periarticular location and pathoanatomically consist of fibrous swelling and central necroses. Other sites of manifestation include involvement of the spleen, liver, and lymph nodes. According to the international classification in “The Care of Rheumatic Children” (EULAR/WHO), there are five different forms of juvenile chronic arthritis (JCA):

Polyarthritic, systemic JCA (Still syndrome): The disease begins in early childhood with fever and sometimes severe organ manifestations.

Polyarthritic, nonsystemic seronegative JCA: This is the largest group, which largely coincides with the adult type of JCA.

Polyarthritic, nonsystemic seropositive JCA: This disease mainly affects girls in late childhood. Rheumatoid and anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA) are positive (ANA in up to 77% of cases).

Oligoarthritis type I: So-called early type; predominantly affects girls, chronic iridocyclitis, ANA positive.

Oligoarthritis type II: So-called late type; predominantly affects boys, sacroiliitis, HLA-B27 positive, can later develop into Marie-Strümpell arthritis (ankylosing spondylitis). Initially and often over a longer period of time, it affects only one or few joints, especially the knee.

When the disease proceeds into adulthood, subcategories 1–3 tend to go into partial remission with osteoarthritic restoration.

Diagnostic Imaging

Radiography

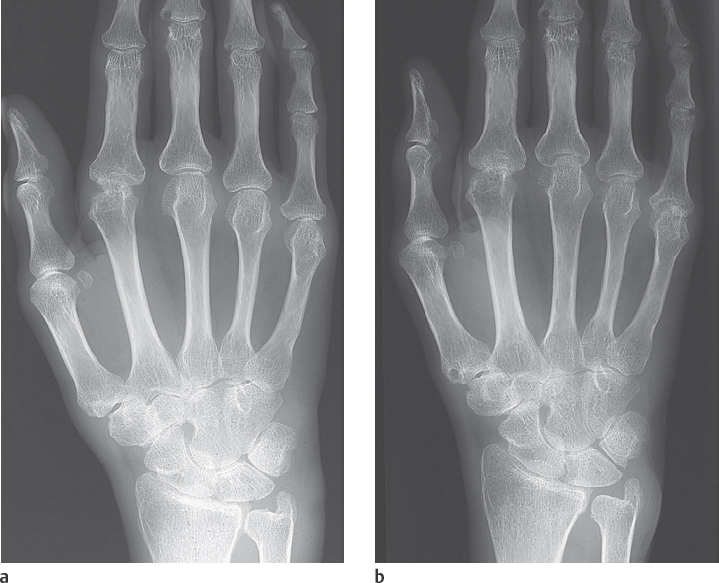

High-resolution radiography systems (screens with a sensitivity of 50) are recommended. Especially in early diagnosis, it is obligatory to take radiographs in two planes; hereby, the “quarter” view (palm down, radial side 20°–25° elevated) is more informative than that in 45° semipronation because the metacarpophalangeal joints often overlap in the latter position. Alternatively, the semisupination oblique view can be employed (Chapter 1). Since 30–50% of cases are categorized in the next higher Larsen stage when these projections are employed, one should not omit the second plane, except in cases of severely mutilating disease. In total, conventional radiography is sufficient to diagnose over 90% of cases, both in early stages and during disease progression.

Arthritic soft-tissue signs: These only become evident days to weeks after disease begins. An increase in volume of the joint cavity is caused by effusion, intra-articular deposits of fibrin, inflammatory infiltration of the synovial membrane, pannus, and edema of the joint capsule and the immediate surrounding tissues. The metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints of both hands in particular are symmetrically affected. Soft-tissue swelling of the carpometacarpal joints in the oblique views, as well as synovial swelling of the tendon sheaths, especially of the extensor carpi ulnaris tendon next to the ulnar head, can often be seen. Synovial inflammation of the bursae, generally around the ulna head, is also visible.

Arthritic collateral signs: These are the radiographic correlates of periarticular decalcification caused by arthritis. They result from hyperemia in the periarticular bone marrow and immobilization caused partially by pain and therapeutic measures, as well as by inflammatory stimulation of osteoclasts.

Arthritic direct signs: Typical of arthritis, but not osteoarthritis, is a uniform, concentric narrowing of the joint space resulting from cartilage destruction caused by inflammation. In dorsopalmar radiographs, these can be simulated in metacarpophalangeal joints by palmar subluxation and in proximal and distal interphalangeal joints by a flexion deformity. Oblique radiographs can clarify the situation.

Typical “early erosions” in palmar-radial or dorsoulnar location can initially be detected only in oblique views. These appear as small defects in the osseous contours directly adjacent to the capsular insertions in the “bare areas,” where the joint surfaces have either only a thin cartilaginous cover or none at all (Fig. 36.3a, b). Disintegration and contour defects in the subchondral bone plate are also primarily located in the bare areas (Fig. 36.2c).

In advanced stages, these marginal erosions increase in size and expand toward the joint center. Further osseous destruction and collapse can be induced by increased articular pressure. Concomitant marginal cysts (geodes) are often observed in the cancellous bone (see Fig. 43.2a, b). Ankyloses develop during the further course of the disease, especially at the wrist joints, with formation of a so-called os carpale ( Fig. 36.5 ). In rare cases, ankyloses can also be observed on the finger joints. More frequently, mutilating destruction of the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints with penciling of the phalangeal condyles and cuplike hollowing of the opposing base (“cup-and-saucer” deformity) can be found (Fig. 36.4a).

Approximately two-thirds of cases have a typical disease pattern, predominantly affecting the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints, including the interphalangeal joint of the thumb. Rheumatoid arthritis also causes erosions of the ulnar styloid process, mainly by the inflamed extensor carpi ulnaris tendon (Fig. 36.3a, b).

Radiographic criteria of adult polyarthritis are summarized in Table 36.4.

The numerous forms of juvenile chronic arthritis have certain peculiarities and are different from the manifestation of adult rheumatoid arthritis. Growth is often impaired as a result of premature closure of the epiphyseal growth plates ( Fig. 36.6 ). This primarily affects the metacarpal bones. A temporary acceleration in growth with an increase in size and epiphyseal and metaphyseal thickening and blunting can also occur. Immobilization and corticoid therapy often lead to osteoporosis and growth retardation. Ankyloses cause malalignment of the affected joints. Subcategories II and III of juvenile chronic arthritis generally cease toward the end of the growing period and heal with “osteoarthritic” deformities.

Arthritic signs in soft-tissues

|

Arthritic signs of periarticular osteopenia

|

Arthritic “direct” signs

|

Pattern of articular manifestation

|

Joint deformities

|

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree