47 Ulnar Tunnel Syndrome (Guyon’s Canal Syndrome)

Guyon’s canal is, after the sulcus of the ulnar nerve in the elbow, the second most likely location for compression neuropathy of the ulnar nerve. Anatomic variations of the nerve and the fibrous tendinous arch within the canal often escape detection in diagnostic imaging, but macroscopic causes of damage to the ulnar nerve, like ganglion cysts, scar tissue, and tumors of the nerve sheath, can be identified with imaging techniques.

Preliminary Remarks on Anatomy

The ulnar tunnel (Guyon’s canal) is located in a mediopalmar position relatively to the carpal tunnel and contains the ulnar artery and nerve ( Fig. 47.1 ). The 1.5-cm-long osteofibrous canal begins at the level of the pisiform and ends at the hook of the hamate. It is bordered by the anatomic structures listed in Table 47.1 .

The palmar branch of the ulnar nerve divides into its superficial and deep branches immediately in front of or in the proximal section of the canal. At the canal exit, the deep nerve branch passes through a narrow area between the hook of the hamate and a fibrous tendinous arch, which serves as the origin of the flexor digiti minimi brevis muscle. At this height, the superficial branch of the nerve passes through the canal in radiopalmar direction. Generally, the nerve and its branches are located on the ulnar side of the ulnar artery. There can be variations in the branches.

Boundary | Anatomic Structure |

Floor |

|

Roof |

|

Ulnar side |

|

Radial side |

|

Pathoanatomy and Clinical Symptoms

The causes listed in Table 47.2 can be responsible for the damage of the ulnar nerve. Isolated or combined neural deficits can occur in sensible function of the ring and little fingers and in the motor function of the hypothenar and intrinsic musculature, depending on the site of damage within Guyon’s canal.

Diagnostic Imaging

Radiography

Fractures, nonunions, osteoarthritic changes, and osteodestructive processes on the ulnar side of the wrist can be identified in survey and special radiographs (carpal tunnel view, semisupinated oblique view of the pisiform). Soft-tissue lesions, with the exception of acute hydroxy-apatite deposits, generally escape radiographic detection.

Ultrasonography

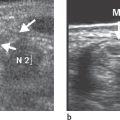

The domain of high-resolution US is the detection of ganglion cysts, which can originate from the pisotriquetral and hamatotriquetral joints or from the tendon sheath of the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle. The diagnostic criterion is an anechoic, delineated space-occupying lesion with a capsule-like margin and distal acoustic enhancement. Other lesions that can easily be recognized in US are aneurysms of the ulnar artery and hypoechoic tumors, which include neurinomas, neurofibromas, and posttraumatic neuromas of the ulnar nerve ( Fig. 47.3 ). US evaluation is limited by acoustic shadowing artifacts at the osteoligamentary structures of the canal.

Computed Tomography

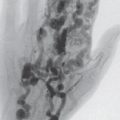

CT is the method of choice for the identification of fractures and nonunions of the hook of the hamate (see Fig. 21.10 ). This type of injury, which is seen more often than expected in everyday clinical routine, should always be taken into consideration when there is a peripheral injury of the ulnar nerve. The branches of the ulnar nerve can be directly injured by fragments of the hook after a trauma or compressed by paraosseous scar tissue ( Fig. 47.2 ). Normally, the ulnar nerve can be visualized up to its division in CT, but after a trauma this is no longer possible because of nerve encasement in scar tissue. The same masking can occur around the ulnar neurovascular bundle in case of inflammatory infiltrates of an acute calcium deposit.

The fibrous tendinous arch that passes over the deep branch of the ulnar nerve at the tunnel exit can be seen in CT only if it is thicker than the normal 2 mm.

The most important soft-tissue tumors or lesions located in Guyon’s canal display the diagnostic criteria listed in Table 47.3 .

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree