8

Head and Neck

Yutaka Sato

Chapter Outline

Chapter Outline

In this chapter, a short overview of head and neck imaging is presented. With the recent advancement and widening availability of sectional imagings, such as CT and MRI, the part played by the plain radiographs has decreased significantly.

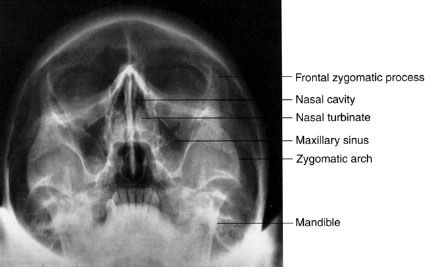

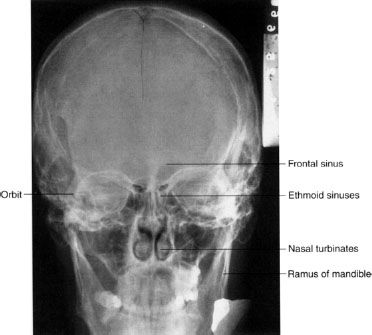

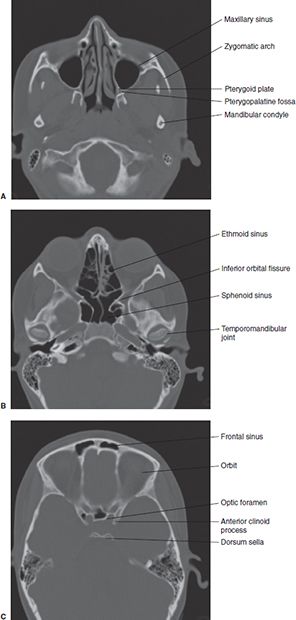

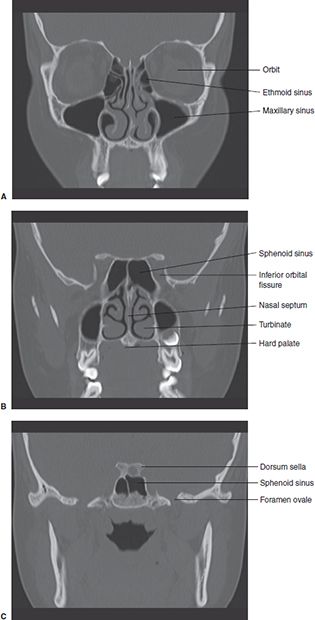

As an initial screening of sinusitis or facial trauma, radiographs may be used when more sophisticated sectional imagings are not readily available. For facial bone and paranasal sinus evaluation, routine radiographic views include Waters (Fig. 8.1), Caldwell (Fig. 8.2), and lateral (Fig. 8.3) views. Lack of aeration in the sinus antra is suggestive of sinusitis, and a definitive diagnosis can be made when an air–fluid level is present. CT is the primary modality for the evaluation of sinus infection and facial trauma (Fig. 8.4) because bone detail is best evaluated by CT. Because of multiple horizontally placed buttresses of the facial skeleton, multiplanar reconstructed images in coronal and sagittal planes generated from axial data are essential for the detailed evaluation of facial fractures (Fig. 8.5).

Ultrasound (US), which does not use radiation, is often sufficient to make diagnosis of nonsurgical mass lesions.

When surgery is contemplated, MRI or CT becomes necessary. MR imaging is the modality of choice for the evaluation of neoplastic lesions of the head and neck, because of its superior soft-tissue characterization and multiplanar capability. MR imaging is essential to evaluate skull-base involvement by head and neck tumors.

SINUSITIS

Clinical presentation of pain, swelling over the paranasal sinuses, and leukocytosis are sufficient for the diagnosis of sinusitis and, in the majority of cases, imaging is not necessary. When intraorbital or intracranial extension of the inflammatory process is suspected and surgical intervention is contemplated, imaging becomes necessary. CT is the modality of choice. Acute fluid collection in the sinus cavity is diagnostic, and associated findings include mucosal thickening (Fig. 8.6) and erosive or destructive changes of the sinus wall. Extension of the inflammatory process into the orbits (Fig. 8.7) or cranial cavity may be seen and helps to determine the therapeutic approach.

For evaluation of children, the developmental sequence of the paranasal sinus should be taken into consideration. Generally, the ethmoid and maxillary sinuses are present at birth, but may not be aerated. The sphenoid and frontal sinuses start to be seen at about 3 and 6 years of age, respectively.

TRAUMA

For the evaluation of facial fractures, CT is also the modality of choice. Nasal fractures are the most common, followed by zygomatic fractures. Zygomatic fractures commonly involve: The lateral orbital wall at the frontozygomatic suture, maxillozygomatic suture, and the zygomatic arch, and is named a “trimalar” or “tripod” fracture (Fig. 8.8). If the facial fracture extends posteriorly and violates the pterygoid plate, the fractured facial bones are detached from the cranium. Depending upon the level of the fracture line traversing the central midface, these fractures are classified as Le Fort I, II, or III fractures (Figs. 8.9 and 8.10).

FIGURE 8.1. Normal Waters view of the face, showing the good delineation of the maxilla. The maxillary sinuses are optimally displayed, and the anterior portions of the orbit and the nasal cavity are clearly outlined.

FIGURE 8.2. A Caldwell, or posteroanterior, view of the face. Note how well the orbits and frontal bone are seen. The maxilla is superimposed on the skull base to some degree. The structures of the internal auditory canals are visible through the orbits.

FIGURE 8.3. Lateral view of the skull shows the posteriorly located sphenoid sinus and the nasopharyngeal airway. This view complements the others, adding the third dimension to the structures of the head and the neck.

FIGURE 8.4. Normal axial CT images: Inferior plane (A), middle plane (B), and superior plane (C).

FIGURE 8.5. Reconstructed coronal CT images: Anterior plane (A), middle plane (B), and posterior plane (C).

FIGURE 8.6. Chronic maxillary sinusitis. The right maxillary sinus is opacified by thickened mucosa, and mucosal thickening extends into the right nasal cavity. Also, notice sclerotic thickening of the sinus wall, suggestive of the chronic nature of the sinusitis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree