8 Suprahyoid Neck(Table 8.8 – Table 8.11)

Disease | CT Findings | Comments |

Congenital/developmental lesions | ||

Infantile hemangioma (capillary hemangioma) | Solitary, multifocal or transspatial, lobular soft tissue mass, homogeneous and isodense with muscle. Contrast enhancement is uniform and intense. No calcifications. Size, enhancement, and vascularity of tumor regress in involutional phase with internal, low-density fat. | True capillary hemangiomas are neoplastic conditions; they typically display a rapid proliferation phase during the first year of life, followed by an involution phase with fatty replacement. They have a female predilection. Infantile hemangiomas are high-flow lesions during their proliferative phase, low-flow lesions in their involutional phase. Sixty percent of infantile hemangiomas occur in the head and neck, with superficial strawberry-colored lesions and facial swelling and/or deep lesions, often in the parotid, masticator, and buccal spaces. Retropharyngeal, sublingual, and submandibular spaces and oral mucosa are other common locations. |

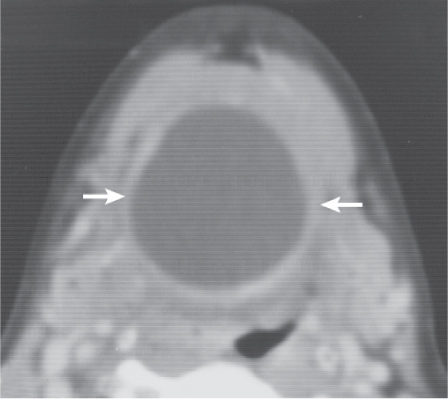

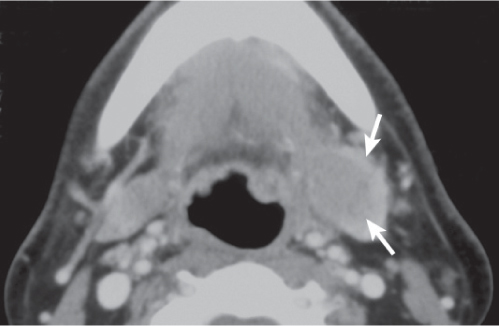

Venous vascular malformation (cavernous hemangioma) | Lobulated or poorly marginated soft tissue mass, isodense to muscle, with rounded calcifications (phleboliths). May be superficial or deep, localized or diffuse, solitary or multifocal, circumscribed or transspatial, with or without satellite lesions. Contrast enhancement is patchy or homogeneous and intense. Bony deformity of the adjacent mandible and fat hypertrophy in adjacent soft tissues may occur. | As opposed to infantile hemangiomas, vascular malformations are not tumors but true congenital low-flow vascular anomalies, have an equal gender incidence, may not become clinically apparent until late infancy or childhood, virtually always grow in size with the patient during childhood, and do not involute spontaneously. Vascular malformations are further subdivided into capillary, venous, arterial, lymphatic, and combined malformations. Venous vascular malformations, usually present in children and young adults, are the most common vascular malformation of the head and neck. The buccal region and dorsal neck are the most common locations. Masticator space, sublingual space, tongue, lips, and orbit are other common locations. Frequently, venous malformations do not respect fascial boundaries and involve more than one deep fascial space (transspatial disease). They are soft and compressible. Lesion may increase in size with Valsalva maneuver, bending over, or crying. Swelling and enlargement can occur following trauma or hormonal changes (e.g., pregnancy). Pain is common and often caused by thrombosis. |

Lymphatic malformation (lymphangioma, cystic hygroma) | Uni- or multiloculated, nonenhancing, fluid-filled mass with imperceptible wall, which tends to invaginate between normal structures. Often found in multiple contiguous cervical spaces (transspatial). Rapid enlargement of the lesion, areas of high attenuation values, and fluid–fluid levels suggest prior hemorrhage. Lymphatic and venous malformation may coexist. | Lymphatic malformations represent a spectrum of congenital low-flow vascular malformations, differentiated by size of dilated lymphatic channels. May be sporadic or part of congenital syndromes (Turner, Noonan, and fetal alcohol syndrome). Macrocystic lymphatic malformation is the most common subtype; 65% are present at birth. Ninety percent are clinically apparent by 3 y of age; the remaining 10% present in young adults. In the suprahyoid neck, the masticator and submandibular spaces are the most common locations. In the oral cavity, lymphatic malformations can occur in the tongue, floor of the mouth, cheek, and lips. The anterior tongue is the most common location for oral cavity lymphangiomas, commonly presenting as an enlarged tongue. |

Lingual (ectopic) thyroid gland | Well-circumscribed midline or paramedian lobulated tongue mass along the course of the thyroglossal duct (foramen cecum area), less commonly in the sublingual space or tongue root. Due to its high iodine content and metabolic activity, the thyroid tissue will appear dense with strong enhancement. Goitrous calcifications and low-density areas may be present. The thyroid gland can be absent from its usual cervical location (complete arrest). | Thyroid tissue in abnormal location in tongue base or floor of mouth. May undergo goitrous or carcinoma-tous transformation. |

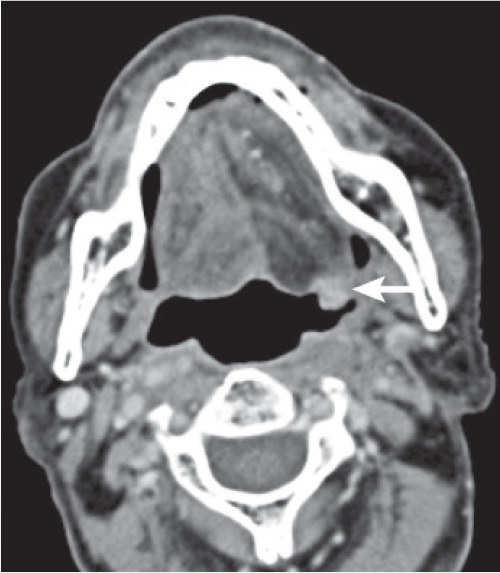

Torus palatinus | Torus palatinus is seen as a flat, spindle-shaped, nodular, or lobular exostosis, which arises in the midportion of the hard palate. Exostoses that are composed of compact bone are of uniform increased bone density. Those that contain a marrow space have trabeculations. Torus mandibularis is an exostosis involving the lingual surface of the mandible just above the mylohyoid line and opposite the premolars; less common than torus palatinus; bilateral in 90% of cases. | Exostoses are localized outgrowths of bone on the surface of the maxilla or mandible (torus mandibularis) that are variable in size, shape, and number (single, multiple exostosis). They are more common in Asian and Inuit populations and twice as common in women. They are more common in early adulthood and can increase in size. |

Inflammatory/infectious conditions | ||

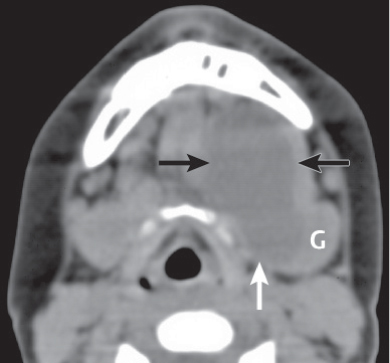

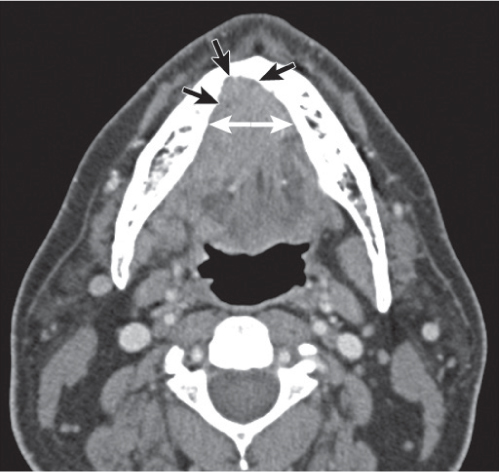

Ludwig angina | CT demonstrates massive edema and an enhancing diffuse, ill-defined infiltration of the superficial and deep tissues of the floor of the mouth, submandibular and sublingual spaces, with low-attenuation areas reflecting abscesses or localized areas of phlegmon. Air in the soft tissues can be the result of gas-producing anaerobic infection. Elevation and backward displacement of the tongue, secondary to marked diffuse swelling, may lead to severe acute airway compromise. | Ludwig angina refers to a potentially lethal acute bilateral cellulitis of the floor of the mouth and submandibular and sublingual spaces that produces gangrene or serosanguineous phlegmon but little or no frank pus. Further spread occurs into the parapharyngeal, retropharyngeal, and carotid spaces, or even into the mediastinum. The source of infection is usually odontogenic, but sublingual or submandibular sialadenitis, trauma, and surgical procedures of the floor of the mouth are also causes of infection. Patients between the ages of 20 and 60 y (rarely seen in children) often present with rapidly progressive facial swelling and induration, oral pain, fever, trismus, dysphagia, dysphonia, and dyspnea. Ludwig angina represents a clinical emergency! |

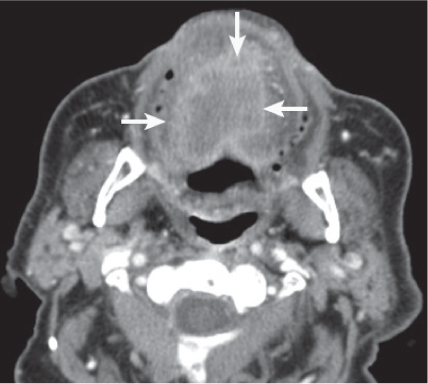

Odontogenic infection | Abscesses appear as single or multiloculated, low-density areas, with or without gas collections, and demonstrate peripheral rim enhancement. Common associated findings are extensive adjacent tongue and soft tissue cellulitis, edematous subcutaneous skin changes with stranding and dermal thickening, increased density of fatty tissue with streaky, irregular enhancement (edematous, “dirty” fat), thickening and enhancement of fasciae, muscular enlargement with enhancement (myositis), and reactive or suppurative adenopathy of submandibular lymph nodes. | Odontogenic infection is most often caused by periapical or periodontal disease related to poor oral hygiene or by extraction of a carious tooth. Odontogenic infection may result in cellulitis, myositis, fasciitis, osteomyelitis, and abscess formation. Odontogenic infections of the maxillary molars may extend into the buccal and masticator spaces. Further spread occurs into the retromolar trigone, parapharyngeal, and submandibular spaces and the floor of the mouth. Infections arising from the mandibular first molar and premolar teeth (the roots of which do not reach below the attachment of the mylohyoid muscle) tend to involve the sublingual space. Infections arising from the lower second and third molar teeth (the roots of which reach below the attachment of the mylohyoid muscle) spread into the submandibular space. |

Benign neoplasms | ||

Benign mixed tumor (pleomorphic adenoma) of the minor salivary glands | Solitary, exophytic, broad-based or pedunculated, sharply marginated, oral submucosal mass, oval to round, isodense to muscle, minimally enhancing, projecting into the oral cavity. May be inhomogeneous with calcifications or cystic components. No deep extension. If the tumor is adjacent to bone (e.g., hard palate), benign-appearing remodeling of bone may be seen. | Benign mixed tumor is the most common benign salivary gland tumor (60%–80%). Eighty percent occur in parotid glands, 8% in submandibular glands, 0.5% in sublingual glands. Seven percent of these benign, heterogeneous tumors arise spontaneously from minor salivary glands that normally line all surfaces of the upper aerodigestive tract. The hard and soft palates are the most common locations. May be found at any age (most common: 50–60 y; M = F). The patient typically presents with a slowly enlarging, painless submucosal tumor. Malignancy may develop in 2% to 10% of lesions (carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma). |

Malignant neoplasms | ||

Squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity |

| Squamous cell carcinoma accounts for 95% of all neoplasms of the oral cavity. It represents 5% of malignant neoplasms in the United States. Clinical tumor stage of oral cavity carcinoma: T1: Tumor is ≤ 2 cm in its greatest dimension. T2: Tumor is > 2 cm but not ≤ 4 cm in its greatest dimension. T3: Tumor is > 4 cm in its greatest dimension. T4a (oral cavity): Tumor invades through cortical bone, into deep/extrinsic muscle of tongue, maxillary sinus, or skin of face. T4a (lip): Tumor invades through cortical bone, inferior alveolar nerve, floor of mouth, or skin (chin or nose). T4b: Tumor invades the masticator space, pterygoid plates, and skull base or encases the internal carotid artery. Thirty to 70% of oral cavity squamous cell carcinomas have malignant lymph nodes at presentation. Distant metastases are not frequent. |

Squamous cell carcinoma of the lip: On CT, the primary tumor may appear as a variably enhancing, invasive soft tissue mass with or without areas of ulceration. Bone erosion usually occurs along the buccal surface of the mandibular or maxillary alveolar ridge. Large tumors may extend directly into the mandible or involve the mental nerve without cortical bone destruction. Metastases to lymph nodes are late and infrequent (< 10% in lower lip cancers). Lower lip lesions metastasize to the submental and submandibular lymph nodes, upper lip lesions to the preauricular, submental, and submandibular lymph nodes. | Most common malignant neoplasm of the oral cavity. 95% of all lip carcinomas originate in the lower lip (0.6% of all cancers in men). Carcinomas of the lips have an indolent and often protracted clinical course. Most common in white men. Peak: fifth to seventh decade. When patients are younger than 40 y, oral cavity malignancy is associated with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) or marijuana use. | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma of the oral tongue: Variably enhancing, infiltrative, ulcerative, and/or exophytic mucosal mass lesion, usually originating along the lateral border or ventral surface of the anterior two thirds of the tongue (lingual tonsil is part of the oropharynx). Advanced tumors tend to grow into the glossotonsillar sulcus, base of the tongue, tonsillar fossa, floor of the mouth, and submandibular space, to cross lingual septum to the opposite half of the tongue, or may invade the mandible. Forty to 70% of patients have regional adenopathy (submandibular nodes, high and midjugular nodes, or lower jugular nodes) at presentation, half of these bilaterally. | Carcinoma of the oral tongue is the second most common site of oral cavity cancer (20% of all oral carcinomas). It is a disease of men. Peak: seventh to eighth decade, but may also be seen in the young. Predisposing factors are poor oral hygiene, tobacco and alcohol use, preexisting Plummer–Vinson syndrome (Scandinavian women), and the coincidence of syphilis. Involvement of the lingual nerve is responsible for the pain in the ipsilateral ear. |

| Squamous cell carcinoma of the floor of the mouth: Poorly circumscribed mass with evidence of invasion on deep margins. Most tumors originate in the anterior portion of the floor of the mouth slightly offthe mid-line. Inferior spread occurs into the sublingual space and may result in obstruction of the submandibular duct and chronic inflammation or infection of the submandibular gland. Infiltration into the mylohyoid muscle signifies involvement of the submandibular space. Superiorly and posteriorly, the tumors tend to involve the ventral surface of the tongue, the adjacent lingual neurovascular bundle, and the base of the tongue. Anteriorly and laterally, the tumor may advance into the adjacent gingival mucosa and may then destroy the cortex of the mandible. The prevalence of lymph node metastasis (submandibular nodes, high jugulodigastric chain) is between 30% and 70%. Bilateral involvement is common. | Squamous cell carcinoma of the floor of the mouth is the third most common tumor of the oral cavity (10%–15% of all oral carcinomas). Occurs predominantly in men in their 60s. It is the most common intraoral site in Africans. |

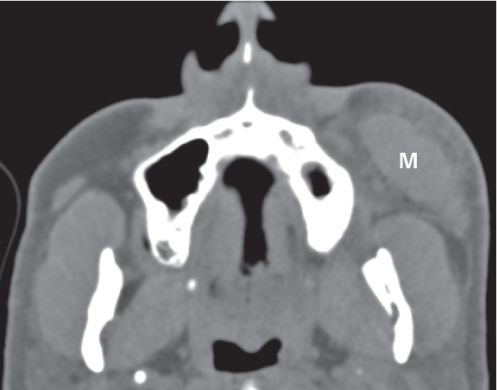

| Squamous cell carcinoma of the buccal mucosa: The growth pattern of buccal carcinomas is usually exophytic, ulcerative, and verrucous. These variably enhancing mass lesions tend to invade the masticator space, the buccinator muscle with subsequent involvement of the skin, the anterior tonsillar pillar, and the soft palate. Pathways of lymphatic spread are variable and include the submandibular, facial, intraparotid, and preauricular nodes. Lymph node metastases are seen early and are present in 50% of cases. | Most buccal carcinomas are encountered in men in their seventh decade with a history of tobacco use or betel nut chewing. Infiltration of the medial pterygoid muscle causes trismus; this may be the first presenting symptom. |

| Squamous cell carcinoma of the gingiva: Frequently occurs in the molar and premolar regions along the gingival margin of a tooth. Destruction of the underlying bone is a frequent finding. Fifty percent of patients have submandibular lymph node metastases at presentation. Squamous cell carcinoma of the retromolar trigone: Can spread to any of the adjacent structures, including the buccal region, tonsils, base of the tongue, skull base, nasopharynx, and floor of the mouth. Osseous invasion of the mandible is common. | The lower jaw is more often affected than the upper jaw. Tumors may present as ulcerating, plaquelike, or nodular lesion. |

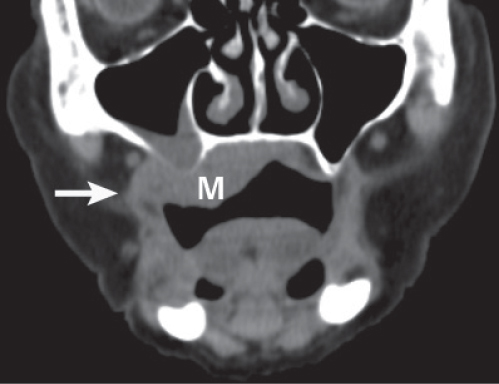

Squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity (continued) | Squamous cell carcinoma of the hard palate: Often confined to its site of origin at the time of diagnosis. Advanced tumors may invade the maxilla, nasal cavity, buccal mucosa, tongue, or retromolar trigone. Perineural extension via the palatine nerves into the pterygopalatine fossa is common. Pathways of lymphatic spread include the facial and retropharyngeal lymph nodes and the upper jugular chain. Thirty percent of patients present with lymph node metastases. | Malignant tumors arising from the hard palate are of squamous cell origin in 50% of cases and of minor salivary gland origin in the remaining 50%. Squamous cell carcinoma of the hard palate predominantly affects elderly men and is strongly related to smoking. |

Minor salivary gland malignancy | Enhancing, poorly circumscribed, diffusely infiltrating, submucosal soft tissue mass, extending into adjacent structures (hard palate, maxilla, sinuses, and buccal mucosa), and adjacent spaces, and invading muscles. Very coarse calcifications may be seen in adenocarcinoma. Associated malignant adenopathy is rare. | Histologically, these tumors include adenoid cystic carcinoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, acinic carcinoma, and pleomorphic adenocarcinoma. Adenoid cystic carcinoma is the most frequent malignant tumor of minor salivary gland origin (25%). Unlike squamous cell carcinoma, tumors of minor salivary gland origin occur in younger patients (third to sixth decade), have an equal male to female ratio, and grow slowly. The patient typically presents with a slowly enlarging, painless submucosal oral cavity mass. Most common locations in the oral cavity are the hard palate–soft palate junction and buccal, labial, and lingual regions. |

Disease | CT Findings | Comments |

Pseudomass | ||

Mandibular nerve motor atrophy | Chronic CN V3 denervation atrophy demonstrates severe atrophy and fatty replacement of the tensor tympani and tensor veli palatini muscles, the muscles of mastication (medial and lateral pterygoid, temporalis, and masseter muscles), and the mylohyoid and anterior belly of the digastric muscles. | Damage to the mandibular nerve anywhere along its course may produce denervation atrophy. Loss of CN V3–innervated muscle volume produces a “hollow concavity” of the cheek (masseter muscle atrophy) or the temporal fossa (temporalis muscle atrophy). The jaw deviates toward the affected side. Denervation of the tensor veli palatini muscle results in a diminutive torus tubarius and eustachian tube function, with accumulation of mastoid fluid. Denervation of the tensor tympani muscle may result in loss of acoustic dampening. May present as pseudotumors because of the relative prominence of the contralateral normal side. |

Accessory salivary tissue | Ovoid to lobulated, homogeneous or heterogeneous submandibular mass, commonly anterior to submandibular gland, with density and contrast enhancement following normal submandibular gland. | Normal salivary tissue in abnormal position within the submandibular space. Usually found incidentally. May present as mass. Accessory salivary gland tissue is susceptible to pathology of normal salivary glands. |

Congenital/developmental lesions | ||

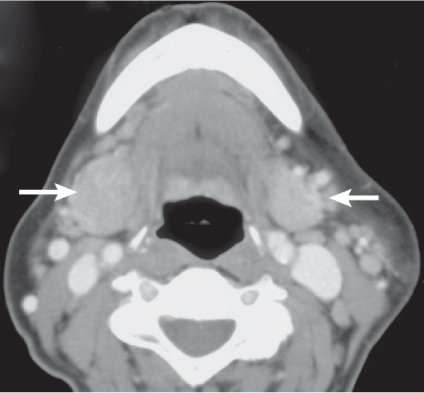

Typical second branchial cleft cyst | Ovoid or rounded, unilocular, low-density cyst (isodense to cerebrospinal fluid), nonenhancing with no discernible wall. Typically occur at the level of the mandibular angle in the posterior submandibular space, anteromedial to the sternocleidomastoid muscle, lateral to carotid space, and posterolateral to the submandibular gland. A beak on the cyst pointing medially between the internal and external carotid arteries is pathognomonic if visualized. If infected, peripheral wall is thicker and enhances, and the density of content increases. “Dirty” fat lateral to the cyst indicates surrounding cellulitis. | Second branchial cleft anomalies represent 95% of all branchial disorders, and cysts are far more common than sinuses and fistulas. Twenty percent are diagnosed in infants and young children and 75% in patients between 20 and 40 y old. Patients present with a painless, compressible lateral neck mass. May get larger with upper respiratory tract infection. If infected, mass becomes painful. If associated fistulous tract is present, cutaneous opening is typically at anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle near middle or lower portion. |

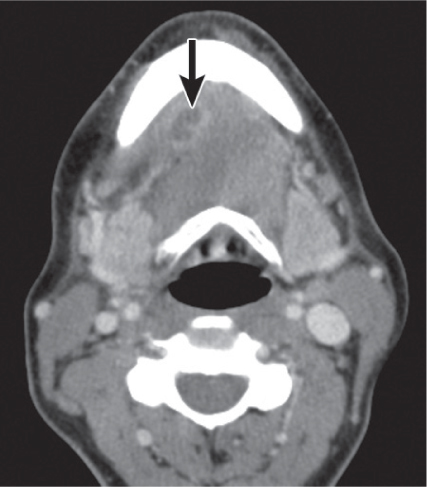

Suprahyoid thyroglossal duct cyst | Well-circumscribed, thin-walled mass of fluid density, unilocular or multilocular, with characteristic anterior midline location entirely within the tongue muscles or in the region of the mylohyoid muscle between the anterior bellies of the digastric muscles, clearly separated from the hyoid bone. Inflammation can alter the density of the cyst, with peripheral rim enhancement and inflammatory changes in the adjacent tissues. A solid mass within the cyst may indicate either associated ectopic thyroid tissue or carcinoma. Calcifications within the soft tissue component may be an indicator of papillary adenocarcinoma. | Thyroglossal duct cysts are the result of incomplete obliteration of the embryonic thyroglossal duct anywhere along its course. Only 20% of these lesions are suprahyoid and may be found from the level of the hyoid bone to the foramen cecum at the tongue base. Presents as a midline mass in the suprahyoid region with fullness in the floor of the mouth, usually detected before the age of 20, frequently following infection. |

Developmental cyst | Dermoid: Unilocular, thin-walled, well-demarcated ovoid mass, with fatty, fluid, or mixed contents. Globules of fat floating within the lesion may produce a characteristic “sack of marbles” appearance. Alternatively, fat–fluid levels may be present. Calcification (< 50%) and a subtle rim enhancement of wall are sometimes seen. Epidermoid: Low-density, unilocular, well-demarcated mass, with fluid contents only, a thin enhancing wall, and no significant surrounding inflammatory changes. Teratoma: Multilocular, heterogeneous, mixed- density mass containing solid, fatty, and cystic components, and calcifications. | Developmental cysts are a rare cause of head and neck masses. They are usually located in the midline or slightly offthe midline within the floor of the mouth, the submandibular or sublingual space, submandibular gland, and root of the tongue. The teratomatous lesions are categorized by their germ cell tissue composition. Epidermoids seem to involve the sublingual space more commonly; dermoids, the submandibular space. They typically become manifest at 5 to 50 y (M:F = 3:1) as a painless subcutaneous or submucosal mass in the suprahyoid region with fullness in the floor of the mouth. The identification of the cyst location in relationship to the mylohyoid muscle on CT or MRI is extremely helpful in surgical planning. |

Infantile hemangioma (capillary hemangioma) | Solitary, multifocal, or transspatial, lobular soft tissue mass, homogeneous and isodense with muscle. Contrast enhancement is uniform and intense. No calcifications. Can be very large, occupying, filling, and expanding the spaces. Size, enhancement, and vascularity of tumor regress in involutional phase with internal, low-density fat. | Congenital capillary hemangioma is the most common infant tumor. Typically presents in early infancy with rapid growth and ultimately involutes via fatty replacement by adolescence. Infantile hemangiomas are high-flow lesions during their proliferative phase, low-flow lesions in their involutional phase. Sixty percent of infantile hemangiomas occur in the head and neck, with superficial strawberry-colored lesions and facial swelling and/or deep lesions, often in the parotid, masticator, and buccal spaces. Retropharyngeal, sublingual, and submandibular spaces and oral mucosa are other common locations. |

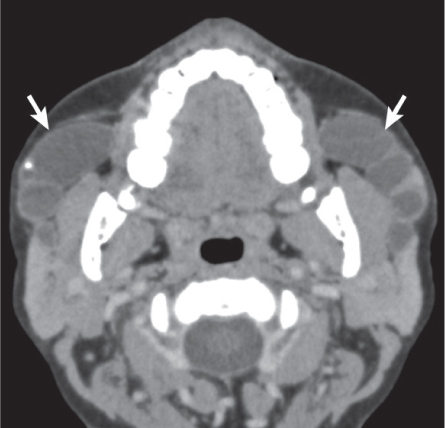

Venous vascular malformation (cavernous hemangioma) | Lobulated or poorly marginated soft tissue mass, isodense to muscle, with rounded calcifications (phleboliths). May be localized or diffuse, solitary or multifocal, circumscribed or transspatial, with or without satellite lesions. Contrast enhancement is patchy or homogeneous and intense. Bony deformity of the adjacent mandible and fat hypertrophy in adjacent soft tissues may occur. | As opposed to infantile hemangiomas, vascular malformations are not tumors but true congenital low-flow vascular anomalies, have an equal gender incidence, may not become clinically apparent until late infancy or childhood, virtually always grow in size with the patient during childhood, and do not involute spontaneously. Vascular malformations are further subdivided into capillary, venous, arterial, lymphatic, and combined malformations. Venous vascular malformations, usually present in children and young adults, are the most common vascular malformation of head and neck. The buccal region and dorsal neck are the most common locations. Masticator space, sublingual space, tongue, lips, and orbit are other common locations. Frequently, venous malformations do not respect fascial boundaries and involve more than one deep fascial space (transspatial disease). They are soft and compressible. Lesion may increase in size with Valsalva maneuver, bending over, or crying. Swelling and enlargement can occur following trauma or hormonal changes (e.g., pregnancy). Pain is common and often caused by thrombosis. |

Lymphatic malformation (lymphangioma, cystic hygroma) | Uni- or multiloculated, nonenhancing fluid-filled mass with imperceptible wall, more commonly in the submandibular than sublingual space. Tends to invaginate posteriorly from the submandibular into the sublingual space or anteriorly into the contralateral submandibular space. Rapid enlargement of the lesion, areas of high attenuation values, and fluid–fluid levels suggest prior hemorrhage. Cyst walls and septa may enhance after contrast material injection. Lymphangiomas may involve the salivary glands directly or by extension. Lymphatic and venous malformation may coexist. | Lymphatic malformations represent a spectrum of congenital low-flow vascular malformations, differentiated by size of dilated lymphatic channels. Macrocystic lymphatic malformation is the most common subtype; 65% are present at birth. Ninety percent are clinically apparent by 3 y of age; the remaining 10% present in adults. They may occur sporadically or with congenital syndrome (e.g., Turner, Noonan, and fetal alcohol syndrome). In the suprahyoid neck, the parotid, masticator, submandibular, sublingual, and parapharyngeal spaces are the most common locations. Compressive symptoms may result from sudden rapid enlargement or following infection or posttraumatic hemorrhage. |

Inflammatory/infectious conditions | ||

Reactive lymphadenopathy | In reactive lymphadenopathy, the submental and submandibular lymph nodes are enlarged (> 10 mm) but maintain their normal oval shape, isodensity to muscle, and homogeneous internal architecture with variable, usually mild enhancement. Enhancing linear markings within the node may be seen. Associated enlargement of lymph nodes in other node-bearing regions of the neck is common. The lingual, faucial, and adenoidal tonsils are often enlarged. | Reactive hyperplasia is a nonspecific lymph node reaction, current or prior to any inflammation in its draining area. Reactive lymphadenopathy also represents the first response of the submandibular lymph nodes to the spread of infection. |

Suppurative lymphadenitis | In suppurative lymphadenitis, the involved nodes are enlarged, ovoid to round, with poorly defined margins and surrounding inflammatory changes. Contrast-enhanced CT images show thick, enhancing nodal walls with central hypodensity, similar to metastatic adenopathy with necrotic center. Extracapsular spread of infection from the suppurative lymph nodes may result in abscess formation. | Infections of the nodal level I lymph nodes commonly occur from dental, floor of the mouth, or buccal infections. Reactive nodes transform into suppurative nodes with intranodal abscess. Common in young patients. Acute/subacute onset of tender mass and fever is seen. |

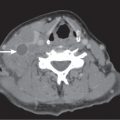

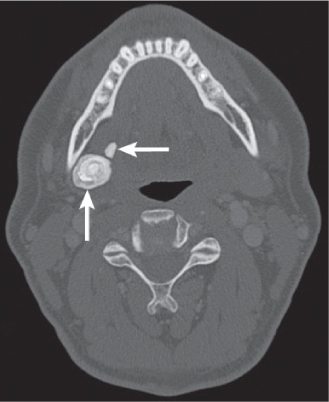

Submandibular sialadenitis | In acute submandibular sialadenitis and sialodochitis secondary to calculus, the submandibular gland duct is dilated, enlarged, and enhancing with surrounding inflammatory changes. Frank abscess formation is rare. In chronic-obstructive submandibular sialadenitis, the submandibular gland is shrunken, fatty infiltrated, with little or no enhancement, and usually associated with duct dilation and calculi. If associated with ductal obstruction from the anterior floor of the mouth squamous cell carcinoma, CT may show an enlarged duct emerging from invasive, enhancing mass and leading to an enlarged, enhancing submandibular gland. If no stone is seen and no tumor is present, sialography will reveal radiolucent stones or a ductal stenosis with a transition in the ductal caliber. | Inflammation of the submandibular gland results from ductal obstruction due to sialolithiasis, fibrous strictures, or a neoplasm obliterating the orifice of Wharton duct. Primary glandular inflammation in Sjögren disease, AIDS, or bacterial or viral infection is rare. Acute submandibular sialadenitis represents with unilateral, painful submandibular gland swelling and colicky pain on eating. Sialolithiasis: Calculi are more common in submandibular gland duct (85%–90%) than parotid gland duct (10%). Sublingual and minor salivary glands are rarely affected. Most calculi (80%–90%) are radiopaque; 25% of patients may have multiple calculi. Submandibular gland duct calculi form at the hilum of the gland or are found in the ductal system. The sialolith may be palpable in the floor of the mouth. |

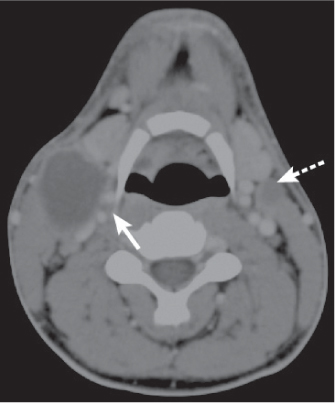

Diving ranula | Unilocular or multilobular, well- circumscribed, low-density mass emanating from sublingual space and extending into adjacent submandibular space (and inferior parapharyngeal space). Diving ranula may be characteristically comet-shaped with collapsed cyst in the sublingual space (“tail” sign) and large pseudocystic component (its “head”) in the posterior submandibular space. Large, horseshoe-shaped ranula may extend across the midline through the anterior isthmus of the sublingual space. | Simple ranula is a mucus retention cyst, acquired secondarily (after trauma to the neck or oral cavity or inflammation) to obstructed sublingual or minor salivary glands, and arises within the sublingual space. The term diving or plunging ranula is used when a simple ranula becomes large and ruptures out of the posterior sublingual space into the submandibular space, creating a pseudocyst lacking epithelial lining. Median age at presentation with painless sublingual and submandibular mass is 30 y. |

Submandibular gland retention cyst (mucocele) | Well-circumscribed, nonenhancing mass lesion of low attenuation values in place of the submandibular gland, conforming to the fascial boundaries of the posterior submandibular space. No sublingual space extension. | Mucus retention cyst of the submandibular gland can be differentiated from a diving ranula by the submandibular gland involvement. |

Cellulitis | Cellulitis of the submandibular space may present as a soft tissue mass with obliteration of adjacent fat planes. It is often ill-defined, enhancing, without focal rim-enhancing fluid collection extending along fascial planes and into subcutaneous tissues beneath thickened skin. Infection of the submandibular space readily extends posteriorly into the parapharyngeal space. | Infection of the submandibular and sublingual spaces is common and can easily pass from one space to the other. Infection of the submandibular space most commonly occurs from suppurative adenopathy associated with dental, floor of the mouth, or buccal infections. Submandibular space infections are often precipitated by submandibular gland inflammation secondary to ductal stenosis or calculus, or it may result directly from odontogenic infection. |

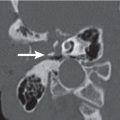

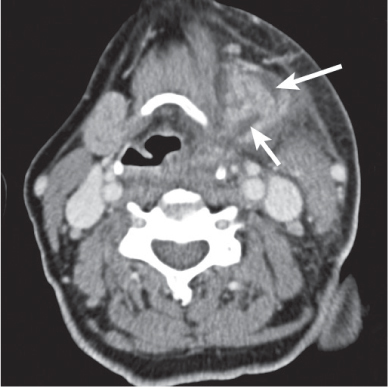

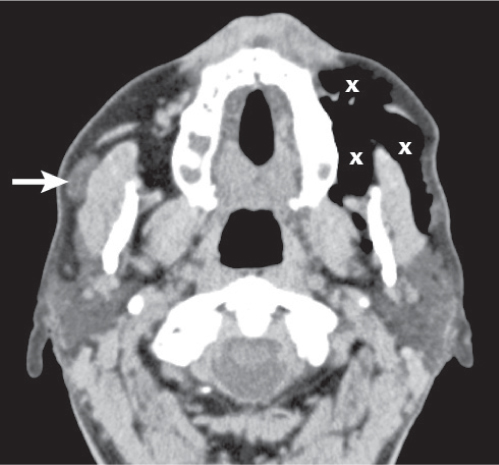

Abscess | Abscesses often appear as a poorly marginated soft tissue mass in the expanded submandibular space with single or multiloculated low-density center, with or without gas collections, and usually thick abscess wall. Contrast-enhanced CT images show a thick, irregular peripheral rim enhancement. May be part of a transspatial abscess. Tooth with periapical abscess and focal mandibular cortex dehiscence or mandibular osteomyelitis with permeative bone changes, focal bone destruction, and periosteal reaction may refer to the source of the infection. Edematous subcutaneous skin changes with stranding and dermal thickening, increased density of fatty tissue with streaky, irregular enhancement (edematous, “dirty” fat), muscular enlargement with enhancement (myositis), and reactive or suppurative adenopathy of submandibular lymph nodes are common associated findings. | Focal collection of pus within oral cavity spaces: sublingual space, submandibular space, root of the tongue, or transspatial. The source of infection is usually odontogenic (tooth root abscess/mandibular osteomyelitis). Infections arising from the lower second and third molar teeth (the roots of which reach below the attachment of the mylohyoid muscle) spread into the submandibular space. Submental space infection may complicate apical and periodontal disease of the incisor teeth. Submandibular duct calculus, sublingual or submandibular sialadenitis, and penetrating trauma are other causes of infection. Further spread occurs into the parapharyngeal and retropharyngeal space. Present in elderly patients with sublingual or submandibular swelling, painful tongue, dysphagia, and dysphonia. Elevation and backward displacement of the tongue may compromise airway. |

Benign neoplasms | ||

Lipoma | Thin-walled, encapsulated, nonenhancing fat-density mass (–65 to –125 HU), homogeneous without any internal soft tissue stranding. Can be transspatial. | Most common sites of origin in the neck are the posterior cervical and submandibular spaces. More common in men (fifth to sixth decade, sometimes in children). |

Benign mixed tumor (pleomorphic adenoma) of submandibular gland | Single, homogeneous ovoid soft tissue mass, with fairly well-defined margins within an enlarged submandibular gland. When large, the intraglandular tumor may pedunculate offthe margin of the gland into the submandibular space. Sometimes foci of fat, necrosis, hemorrhage, or focal calcifications may be seen. The contrast enhancement, mild to moderate, may be uniformly homogeneous or heterogeneous. | Fifty-five percent of submandibular gland tumors are benign, 45% malignant. Benign mixed tumor is the most common tumor of the submandibular gland; 8% of all head and neck benign mixed tumors arise in the submandibular gland. Presents as slow-growing, painless submandibular space mass. Peak age of occur-rence is 40 y and older; (M:F = 1:2). If left untreated, 10% to 25% of benign mixed tumors will undergo malignant transformation. |

Pedunculated parotid tail mass | Solid or cystic mass at the level of the mandibular angle, located anterolateral to sternocleidomastoid muscle and lateral to posterior belly of digastric muscle, medial and deep to the platysma muscle. May mimic a posterior submandibular space lesion. | A pedunculated parotid tail tumor can easily be mistaken for a nonparotid mass on axial images. Benign mixed tumor and Warthin tumor are the most common solitary mass lesions of the most inferior aspect of the superficial parotid gland lobe. |

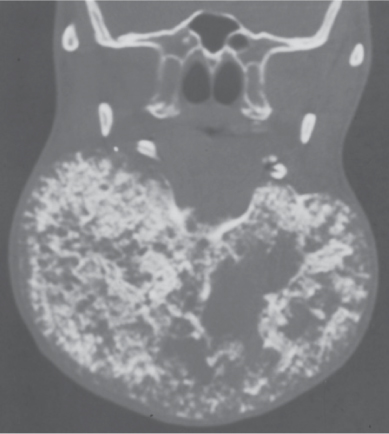

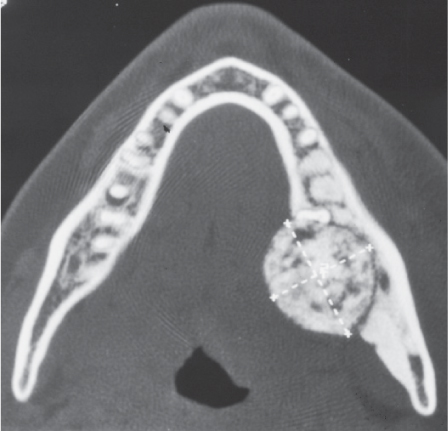

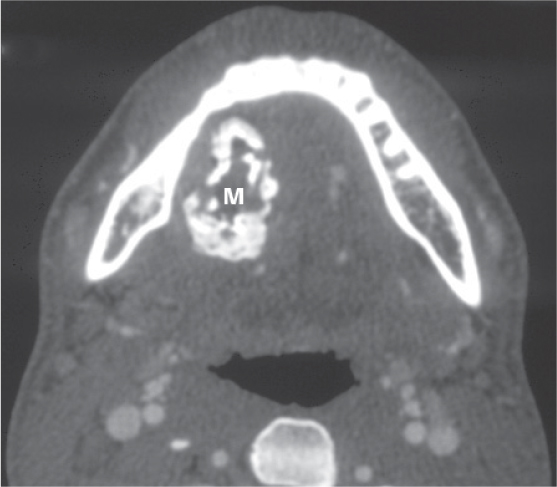

Ameloblastoma | Usually centered in third molar, mandibular ramus region. Enhancing, expansile, uni- or multicystic, low-density mass with “bubbly pattern,” internal osseous septa, usually no calcifications in matrix, scalloped borders, and thinned cortical margins with focal areas of dehiscence. Unerupted molar tooth and resorption of adjacent tooth roots association are common. No evidence of perineural spread. Extraosseous extension into the major areas of the oral cavity or masticator space is rare. | Most common benign mandibular tumor. Most common odontogenic tumor (35%), mandible:maxilla = 5:1. Twenty percent of ameloblastomas are thought to arise from dentigerous cysts. Most commonly presents in 30- to 50-y-olds with painless, slow-growing mandibular mass, loose teeth, bleeding, and trismus. Malignant transformation is rare (1%). Other benign odontogenic tumors are calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumor, ameloblastic fibroma, adenomatoid odontogenic tumor, dentinoma, calcifying odontogenic cyst, odontogenic ameloblastoma, odontomas, and cementomas. Benign nonodontogenic tumors and cysts are found not only in the jaw bone but also in other areas of the skeleton. |

Malignant neoplasms | ||

Nodal metastases | Single or grouped lymph nodes centered within the fat of the submandibular space outside the submandibular gland, round (with a longitudinal-to-transverse diameter ratio < 2), variable in size (maximal longitudinal diameter > 15 mm), with heterogeneous enhancement. Nodal tumor necrosis appears as a central nonenhancing low-density mass with variably thick, irregular, moderately enhancing wall. Metastatic nodes may be completely cavitated by cystic degeneration, mimicking a benign cyst (e.g., squamous cell carcinoma of the area of Waldeyer ring and papillary thyroid carcinoma). Ill-defined margins and stranding of surrounding fat are features of extracapsular spread. | Malignant tumor of the submandibular space is nodal tumor in the vast majority of cases. Metastatic involvement of submental (level IA) and submandibular (level IB) lymph nodes typically occurs in association with primary head and neck squamous cell carcinomas of the skin of face, oral cavity structures, nose, and anterior sinus regions. A painless, firm submandibular space mass may be the presenting symptom, most commonly in patients with known primary (M > F, > 40 y). |

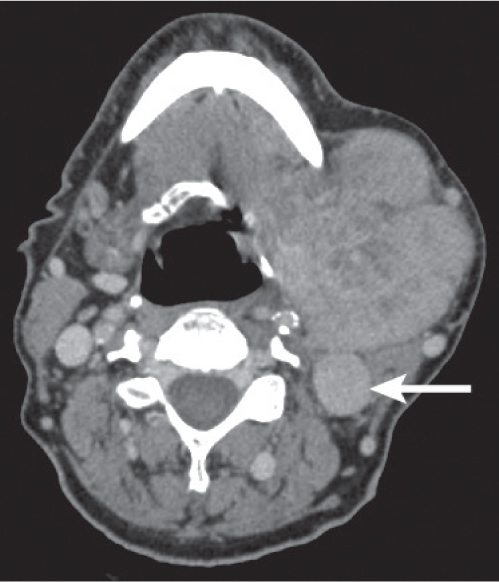

Nodal non–Hodgkin lymphoma | Bilateral, multiple, well-demarcated, homogeneous, nonnecrotic enlarged nodes throughout submandibular space, isodense to muscle, with variable diffuse enhancement and generally no extracapsular extension. Dominant node may reach 5 to 10 cm in size. Extranodal tumor extension, nodal necrosis, calcification, and hemorrhage are rare prior to treatment (high-grade non–Hodgkin lymphoma may show central node necrosis, mimicking metastasis from squamous cell carcinomas). | Nodal non–Hodgkin lymphoma of the submandibular space usually occurs in association with manifestations in various deep lymphatic chains of the neck. Clinical: painless, multiple, rubbery submandibular space masses. Systemic symptoms include night sweats, recurrent fevers, unexplained weight loss, and fatigue (median age of occurrence 50–55 y; M:F = 1.5:1). |

Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the submandibular gland | Smaller tumors may present as a well-circumscribed, relatively homogeneous mass with mild enhancement arising within or from the enlarged submandibular gland. When large, the inhomogeneous enhancing mass may show irregular calcifications and emanate from the submandibular gland into the submandibular space with invasive margins. Adenoid cystic carcinoma has a propensity to infiltrate and spread along perineural planes. | Malignancy of the submandibular gland is rare. Adenoid cystic carcinoma is the most common submandibular gland carcinoma. It accounts for 4% to 8% of total salivary gland tumors, 30% of minor salivary gland tumors, 15% of sublingual gland tumors, 12% of submandibular gland tumors, and 2% to 6% of parotid gland tumors. Most patients with a submandibular gland carcinoma are women in their fourth to sixth decades who present with a painless submandibular swelling. |

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the submandibular gland | Low-grade lesions are generally better circumscribed, contain more cysts, may be hemorrhagic, and may appear benign with well-defined margins. Higher-grade lesions are more solid, isodense, and aggressive and may show infiltration, necrosis, and calcification. Contrast enhancement is usually mild to moderate. | Mucoepidermoid carcinoma accounts for < 10% of salivary gland tumors and 30% of salivary gland malignancies. Fifty-four percent are present in the major salivary glands, 46% in the intraoral minor salivary glands. Exposure risk: radiation. It usually occurs in patients younger than age 50, but it is the most common malignant salivary gland tumor in children. |

Metastases to the submandibular gland | May be a fairly well-circumscribed mass or less defined and infiltrative, replacing portions of the enlarged submandibular gland. | Metastatic deposits in the submandibular gland are extremely rare and due to direct extension from a primary oral cavity lesion or as a result of hematogenous spread (melanoma, breast cancer, papillary thyroid cancer, and uterine leiomyosarcoma). |

Contiguous tumor extension | Carcinoma of the tongue and floor of the mouth has CT density similar to normal tongue muscle. Direct invasion of the sublingual and submandibular spaces is recognized by obliteration of the normal fat planes and by contrast enhancement of the tumor margins. | Advanced carcinomas of the tonsil, tongue, and floor of the mouth may spread into the sublingual spaces, tongue muscles, and submandibular spaces. |

Malignant mandibular tumors | In advanced cases, cortical breakthrough with tumor outside of the jaw is a common finding. When the body or symphysis is the principal site of tumor, soft tissue extension involves the submandibular space or sublingual space, depending on from which side of the mylohyoid muscles the mass originates. | Malignant mandibular neoplasms are rare and often occur in younger people. They include osteogenic sarcoma, chondrosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, malignant lymphoma, multiple myeloma, Burkitt lymphoma, leukemia, and metastases. |

Disease | CT Findings | Comments |

Pseudomass | ||

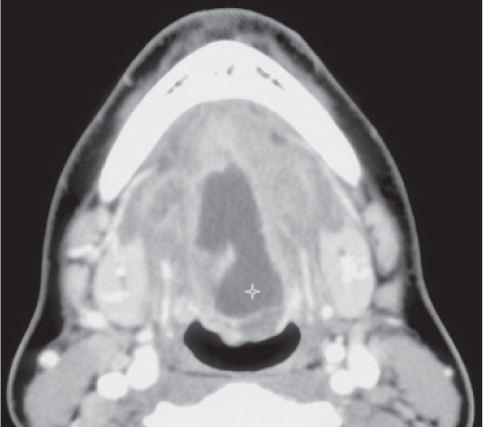

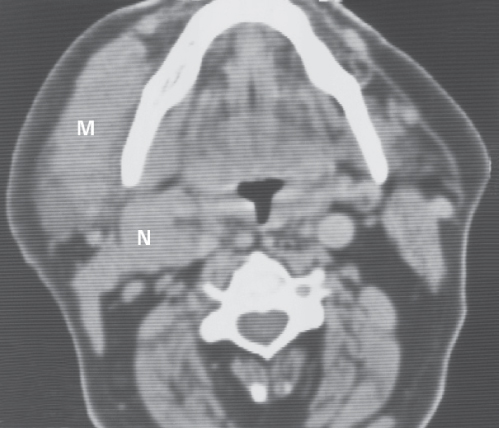

Hypoglossal nerve motor atrophy | In CN XII injury, the intrinsic and extrinsic tongue muscles are affected. Long-standing chronic denervation is manifested by marked loss of hemitongue volume, extensive fatty replacement, absence of contrast enhancement, and ipsilateral deviation of the midline fatty septum. A characteristic finding in chronic hypoglossal denervation is the prolapse of the affected hemitongue posteriorly into the oropharynx. | Damage to the hypoglossal nerve anywhere along its course may produce denervation atrophy. Patients who have denervation atrophy of muscles innervated by the hypoglossal nerve demonstrate loss of hemitongue volume, loss of normal papillae, and deviation of the tongue toward the side of pathologic change on protrusion. |

Congenital/developmental lesions | ||

Infantile hemangioma (capillary hemangioma) | Solitary, multifocal, or transspatial, lobular soft tissue mass, homogeneous and isodense with muscle. Contrast enhancement is uniform and intense. No calcifications. Size, enhancement, and vascularity of tumor regress in involutional phase with internal, low-density fat. | True capillary hemangiomas are neoplastic conditions; they typically display a rapid proliferation phase during the first year of life, followed by an involution phase with fatty replacement. They have a female predilection. Infantile hemangiomas are high-flow lesions during their proliferative phase, low-flow lesions in their involutional phase. Sixty percent of infantile hemangiomas occur in the head and neck, with superficial strawberry-colored lesions and facial swelling and/or deep lesions, often in the parotid, masticator, and buccal spaces. Retropharyngeal, sublingual, and submandibular spaces and oral mucosa are other common locations. |

Venous vascular malformation (cavernous hemangioma) | Lobulated, well-defined, or poorly marginated soft tissue mass, isodense to muscle, with rounded calcifications (phleboliths). May be localized or diffuse, solitary or multifocal, circumscribed or transspatial, with or without satellite lesions. Contrast enhancement is patchy or homogeneous and intense. Fat hypertrophy in adjacent soft tissues may be present. | As opposed to hemangiomas, vascular malformations are not tumors but true congenital low-flow vascular anomalies, have an equal gender incidence, may not become clinically apparent until late infancy or childhood, virtually always grow in size with the patient during childhood, and do not involute spontaneously. Vascular malformations are further subdivided into capillary, venous, arterial, lymphatic, and combined malformations. Venous vascular malformations, usually present in children and young adults, are the most common vascular malformation of the head and neck. The buccal region and dorsal neck are the most common locations. Sublingual space, masticator space, tongue, lips, and orbit are other common locations. Frequently, venous malformations do not respect fascial boundaries and involve more than one deep fascial space. They are soft and compressible. Lesion may increase in size with Valsalva maneuver, bending over, or crying. Rapid swelling and enlargement can occur following trauma or hormonal changes (e.g., pregnancy). Pain is common and often caused by thrombosis. |

Lymphatic malformation (lymphangioma, cystic hygroma) | Uni- or multilocular, often poorly circumscribed and transspatial, insinuating nonenhancing, fluid-density mass. Fluid–fluid levels may be seen. If uninfected, the wall may be very thin. | Lymphatic malformations represent a spectrum of congenital low-flow vascular malformations, differentiated by size of dilated lymphatic channels. May be sporadic or part of congenital syndromes (Turner, Noonan, and fetal alcohol syndromes). Macrocystic lymphatic malformation is the most common subtype; 65% are present at birth. Ninety percent are clinically apparent by 3 y of age; the remaining 10% present in young adults. In the suprahyoid neck, involvement of the masticator, submandibular, parotid, and parapharyngeal spaces is more common than involvement of the sublingual space. Lymphatic malformations may involve the salivary glands directly or by extension. Large lesions can present with airway obstruction. |

Developmental cyst | Dermoid: Unilocular, thin-walled, well-demarcated ovoid mass with fatty, fluid, or mixed contents. Globules of fat floating within the lesion may produce a characteristic “sack of marbles” appearance. Alternatively, fat–fluid levels may be present. Calcification (< 50%) and subtle rim enhancement of the wall are sometimes seen. Epidermoid: Low-density, unilocular, well-demarcated mass with fluid contents only, a thin enhancing wall, and no significant surrounding inflammatory changes. Teratoma: Multilocular, heterogeneous, mixed- density mass containing solid, fatty, and cystic components and calcifications. | Developmental cysts are a rare cause of head and neck masses. They are usually located in the midline or slightly offthe midline within the floor of the mouth, the anterior submandibular or sublingual space, the submandibular gland, and the root of the tongue. The teratomatous lesions are categorized by their germ cell tissue composition. Epidermoids seem to involve the sublingual space more commonly; dermoids, more commonly the submandibular space. Present from birth, oral cavity space cysts typically become manifest at age 5 to 50 y (M:F = 3:1) as a painless subcutaneous or submucosal mass in the suprahyoid region with fullness in the floor of the mouth. The identification of the cyst location in relationship to the mylohyoid muscle on CT or MRI is extremely helpful in surgical planning. |

Lingual thyroid tissue | High-density mass secondary to iodine accumulation, sharply marginated, with avid homogeneous enhancement, usually at the midline of the base of the tongue along the expected tract of the thyroglossal duct. Less commonly found in the sublingual space or tongue root. | Aberrant thyroid can be found in many locations in the neck and mediastinum. A lingual (base of the tongue) location of the thyroid may represent the only undescended thyroid tissue in the body. Ectopic thyroid tissue has a high female-to-male preponderance. There are two presentation age peaks: around puberty and in the elderly. Symptoms may arise from local mass effect; hyperthyroidism is rare. Lesions that occur in a cervical thyroid gland can also be found in ectopic glandular tissue, including goiter and different types of carcinoma, but most commonly papillary carcinoma. |

Inflammatory/infectious conditions | ||

Ludwig angina | CT demonstrates massive edema and an enhancing diffuse, ill-defined infiltration of the superficial and deep tissues of the floor of the mouth, submandibular and sublingual spaces, with low-attenuation areas reflecting abscesses or localized areas of phlegmon. Cellulitis appears as thickening of the cutis and subcutis and increased density of fatty tissue with streaky, irregular enhancement (edematous, “dirty” fat). Myositis appears as thickening and enhancement of muscles. Fasciitis appears as thickening and enhancement of fasciae. Air in the soft tissues can be the result of gas-producing anaerobic infection. Elevation and backward displacement of the tongue, secondary to marked swelling, may lead to severe acute airway compromise. | Ludwig angina refers to a potentially lethal acute bilateral cellulitis of the floor of the mouth and submandibular and sublingual spaces that produces gangrene or serosanguineous phlegmon but little or no frank pus. Further spread occurs into the parapharyngeal, retropharyngeal, and carotid spaces, or even into the mediastinum. The source of infection is usually odontogenic, but sublingual or submandibular sialadenitis, trauma, or surgical procedures of the floor of the mouth are also causes of infection. Patients between the ages 20 and 60 y (rarely in children) often present with rapidly progressive facial swelling, oral pain, fever, dysphagia, dysphonia, and dyspnea. Ludwig angina represents a clinical emergency. |

Abscess | Abscesses appear as single or multiloculated, low-density areas, with or without gas collections, and demonstrate peripheral rim enhancement. Central root of the tongue abscesses begin in the midline septum area between the genioglossus muscles. Sublingual space abscesses may be unilateral, with fluid collection superomedial to the mylohyoid muscle, or bilateral, with a horseshoe-shaped fluid collection connected by anterior isthmus. Tooth with periapical abscess and focal mandibular cortex dehiscence or mandibular osteomyelitis with permeative bone changes, focal bone destruction, and periosteal reaction may refer to the source of the infection. Edematous subcutaneous skin changes with stranding and dermal thickening, increased density of fatty tissue with streaky, irregular enhancement (edematous, “dirty” fat), muscular enlargement with enhancement (myositis), and reactive or suppurative adenopathy of submandibular lymph nodes are common associated findings. | Focal collection of pus within oral cavity spaces (sublingual space, submandibular space, root of the tongue, or transspatial). The source of infection is usually odontogenic (tooth root abscess/mandibular osteomyelitis). Infections arising from the mandibular first molar and premolar teeth (the roots of which do not reach below the attachment of the mylohyoid muscle) tend to involve the sublingual space. Infections arising from the lower second and third molar teeth (the roots of which reach below the attachment of the mylohyoid muscle) spread into the submandibular space. Submandibular duct calculus, sublingual or submandibular sialadenitis, and penetrating trauma are other causes of infection. Further spread occurs into the parapharyngeal and retropharyngeal space. |

Necrotizing fasciitis | The CT findings consist of thickening of the cutis and subcutis, thickening and enhancement of the cervical fascia and muscles (fasciitis and myositis), and fluid collections in multiple neck spaces (including oral cavity, carotid, parapharyngeal, retropharyngeal, perivertebral, and masticator spaces), air collections with fluid collections, and reactive lymphadenopathy. Vascular complications include erosion and rupture of the carotid artery and thrombosis of the internal jugular vein. | Necrotizing fasciitis is a severe, acute, and potentially life-threatening streptococcal or mixed bacterial soft tissue infection with a very rapid clinical evolution. It can follow any infection in the neck and is usually characterized in the early stages by neck swelling, erythema, and fever. The infection spreads rapidly throughout the tissue planes of the neck. Failure to treat may lead to sepsis and mediastinitis. It occurs predominantly in immunocompromised and elderly patients. |

Dilated submandibular gland duct | CT demonstrates a dilated submandibular gland duct in the sublingual space that can be followed back into the gland (confirming that this is not a ranula). Complete obstruction of the duct leads to atrophy of the gland. | Partial obstruction of the submandibular gland duct can be congenital or caused by calculus or stricture secondary to calculus, trauma, infection, or neoplasm. Thirty percent of salivary glands with sialolithiasis have associated single or multiple stenoses. Symptoms include intermittent swelling, pain with eating, and superimposed infection secondary to stasis. |

Sialocele | True sialocele: Sublingual space mass, smoothly bordered, ovoid to lenticular with fluid density in the course of the dilated submandibular duct. If associated with sialolithiasis, CT may show duct enlargement with enhancing enlarged submandibular gland and enhancing adjacent inflammatory soft tissues. With false sialocele , fluid collection is distinct from the submandibular duct. | Partial obstruction of the distal end of the submandibular duct, usually caused by sialolithiasis, inflammation, or a tumor, will produce dilation of the duct with focal distention representing an epithelial-lined salivary mucocele or salivary retention cyst. Disruption of the duct, usually caused by trauma or surgery, will cause extrusion of saliva into the adjacent tissue, resulting in a pseudocyst, contained within a fibrous pseudo capsule (false sialocele). |

Ranula, simple or diving | Simple ranula: Sharply marginated, unilateral, oval to lenticular, unilocular, homogeneous, low-density (0–20 HU) mass confined to the sublingual space with thin, nonenhancing wall. Wall thickening and minimal internal septa formation can be noted after infection or surgery. Diving ranula: Unilocular or multilobular, well-circumscribed, low-density mass emanating from the sublingual space and extending into the adjacent submandibular space and inferior parapharyngeal space. Diving ranula may be characteristically comet-shaped with collapsed cyst in the sublingual space (“tail” sign) and large pseudocystic component (its “head”) in the posterior submandibular space. Large, horseshoe-shaped ranula may extend across the midline through the anterior isthmus of the sublingual space. | Ranulas are rare lesions. Simple ranula is a mucus retention cyst, acquired secondarily (after trauma or inflammation) to obstructed sublingual or minor salivary glands, that arises within the sublingual space. The term diving or plunging ranula is used when a simple ranula becomes large and ruptures out of the posterior sublingual space into the submandibular and inferior parapharyngeal spaces, creating a pseudocyst lacking epithelial lining. Simple ranulas are seen as intraoral mass lesions. Diving ranulas are seen as submandibular or neck masses with no clinically apparent oral connection. |

Benign neoplasms | ||

Benign mixed tumor (pleomorphic adenoma) of sublingual gland origin | Single, homogeneous, ovoid soft tissue mass with fairly well-defined margins in the sublingual space. Sometimes foci of necrosis, hemorrhage, or focal calcifications may be seen. The contrast enhancement, mild to moderate, may be uniformly homogeneous or heterogeneous. | Only 0.5% to 1% of all head and neck benign mixed tumors arise in the sublingual gland. Presents as slow-growing, painless sublingual space mass. Peak age of occurrence 40 y and older; M:F = 1:2. |

Malignant neoplasms | ||

Contiguous tumor extension | Aggressive, fairly enhancing mixed-density mass lesion violating the sublingual space. Tongue base carcinoma invades the sublingual space from posterior to anterior, oral tongue carcinoma invades it from superior to inferior. | The most common malignant lesion of the sublingual space is a squamous cell carcinoma arising from the epithelial covering of the sublingual space or related to direct extension of oropharyngeal carcinoma. |

Malignant sublingual gland or minor salivary gland tumor | Small well defined or larger poorly, irregular defined soft tissue mass in the sublingual space with heterogeneous enhancement. Mucoepidermoid carcinomas have a strong tendency to spread into local lymph nodes. Distant adenoid cystic carcinoma metastases occur most often in lungs. | Eighty percent of all sublingual gland masses are malignant. Malignant tumors of the sublingual gland, and minor salivary gland origin include adenoid cystic carcinoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma, malignant mixed tumor (carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma), metasta-sizing benign mixed tumor, and carcinosarcoma. Patients (30–60 y, M = F) present with painless sublingual space swelling. |

Disease | CT Findings | Comments |

Pseudomass | ||

Accessory parotid gland | Accessory parotid tissue may be unilateral or bilateral, overlying the anterior margin of the masseter muscle outside the masticator space, and has the same attenuation as the tissue in the main parotid gland. | In 20% to 35% of healthy patients, accessory parotid tissue is present in the buccal space, separate from and anterior to the parotid gland, immediately to the parotid duct. May mimic a buccal mass on clinical examination. |

Congenital/developmental lesions | ||

Developmental cyst | Dermoid: Cystic, well-demarcated mass, localized in the buccal space, adjacent to the skin and distinct from the buccinator muscle, with fatty, fluid, or mixed contents. Globules of fat floating within the lesion may produce a characteristic “sack of marbles” appearance. Alternatively, fat–fluid levels may be present. Calcifications (< 50%) and a subtle rim enhancement of wall are sometimes seen. Epidermoid: Low-density, unilocular, well-demarcated mass localized in the buccal space, with fluid contents only, a thin wall, and no significant surrounding inflammatory changes. Teratoma: Multilocular, heterogeneous, mixed-density mass, containing solid, fatty, and cystic components and calcifications. | Developmental cysts are a rare cause of head and neck masses. They typically become manifest during the second or third decade of life. |

Infantile hemangioma (capillary hemangioma) | Solitary, multifocal or transspatial, lobular soft tissue mass, homogeneous and isodense with muscle. Contrast enhancement is uniform and intense. No calcifications. Size, enhancement and vascularity of tumor regress in involution phase with internal, low-density fat. | True capillary hemangiomas are neoplastic lesions. They tend to be small or absent at birth, typically enter a rapid proliferation phase during the first year of life, followed by a stationary period and, finally, an involution phase with fatty replacement. They have a female predilection. Infantile hemangiomas are high-flow lesions during their proliferative phase, low-flow lesions in their involutional phase. Sixty percent of infantile hemangiomas occur in the head and neck, with superficial strawberry-colored lesions and facial swelling and/or deep lesions, often in the parotid, masticator, and buccal spaces. Retropharyngeal, sublingual, and submandibular spaces and oral mucosa are other common locations. |

Venous vascular malformation (cavernous hemangioma) | Multilobulated, well-defined, or poorly marginated soft tissue mass, isodense to muscle. May be located superficially or involve deep structures, localized or diffuse, solitary or multifocal, circumscribed or transspatial, with or without satellite lesions. Contrast enhancement is patchy or homogeneous and intense. The presence of characteristic phleboliths will strongly suggest the diagnosis. | Unlike infantile hemangiomas, vascular malformations are true congenital low-flow vascular anomalies, have an equal gender incidence, are always present at birth, and enlarge proportional to growth. They never involute and remain present throughout life. Vascular malformations are further subdivided into capillary, venous, arterial, lymphatic, and combined malformations. Venous vascular malformations, usually present in children and young adults, are the most common vascular malformation of the head and neck. The buccal region and dorsal neck are the most common locations. Masticator space, sublingual space, tongue, lips, and orbit are other common locations. Frequently, venous malformations do not respect fascial boundaries and involve more than one deep fascial space (transspatial disease). They are soft and compressible. Lesions may increase in size with Valsalva maneuver, bending over, or crying. Rapid swelling and enlargement can occur following trauma or hormonal changes (e.g., pregnancy). Pain is common and often caused by thrombosis. |

Inflammatory/infectious conditions | ||

Cellulitis | Cellulitis may present as a soft tissue mass with edematous obliteration of adjacent fat planes but without a definite low-density collection of pus. It is often ill defined, enhancing, and extending along fascial planes and into subcutaneous tissues beneath thickened skin. | Buccal space cellulitis may arise from an infection of the masticator space or oral cavity. Commonly occurs in children younger than 3 y (F = M) in fall/winter with fever, buccal swelling, and blue-red skin color; 17% are associated with ipsilateral serous otitis media. |

Abscess | Abscesses often appear as a poorly marginated soft tissue mass in the expanded buccal space with single or multiloculated low-density center, with or without gas collections, and usually thick abscess wall. Contrast-enhanced CT images show a thick, irregular peripheral rim enhancement and enhancement of the inflamed adjacent soft tissues. From the buccal and masticator space, the abscesses may spread into the retromolar trigone, parapharyngeal space, submandibular space, and floor of the mouth. | Odontogenic infections of the maxillary molars may produce bacterial abscesses in the buccal space and masticator space. Less commonly, they may result from infections of buccal lymph nodes or minor salivary glands. They may occur in all age groups with an acute onset (risk factors: history of diabetes mellitus and Crohn disease). Patients may be toxic, febrile, dehydrated, and present with a tender, swollen cheek and a fluctuating mass. |

Benign neoplasms | ||

Benign epithelial tumors of salivary gland origin | Well-circumscribed, rounded, isoattenuating mass with moderate contrast enhancement. Central areas of low attenuation and rim enhancement, calcifications, and cysts are possible in larger tumors. | The most common primary masses in the buccal space are salivary gland tumors. Benign mixed tumor (pleomorphic adenoma) is the most common benign tumor of the salivary glands. It is 9 times as common in the accessory parotid gland as in minor salivary glands. Presents as slow-growing, nontender buccal space mass. Peak age of occurrence 40 y and older; M:F = 1:2. Other benign salivary gland lesions (e.g., monomorphic adenomas and ductal papillomas) may have similar clinical and imaging characteristics. |

Lipoma | Well-defined, nonenhancing fat-density mass (–65 to –125 HU), homogeneous without any internal soft tissue stranding. | Lipomas of the buccal space are uncommon. Present as slowly enlarging palpable mass. Peak age of occurrence 40 y and older; M:F = 2.5:1. |

Neurofibroma | May present as solitary or multiple, rounded or ovoid, well-demarcated, heterogeneous, low-density mass. Absence of contrast enhancement is conspicuous. Plexiform neurofibroma shows a usually large, illdefined, more infiltrative, heterogeneous mass with a mixed-density pattern. A typical finding is the target sign with a punctate high attenuation centrally surrounded by peripheral low attenuation within multiple small tumor nodules. | Neurofibromas involving the buccal space are usually associated with neurofibromatosis type 1. They may be localized, solitary or multiple, or plexiform. |

Schwannoma | Schwannomas tend to occur as a well-defined, fusi-form soft tissue mass with varying degrees of contrast enhancement. Some of the nerve tumors may be extensive, multilobulated, with areas of cystic formation and inhomogeneous enhancement. | Schwannomas of the buccal space are very rare. They are usually solitary and manifest as a slowly enlarging, painless mass along the branches of the facial or mandibular nerves. These tumors can occur at any age, most commonly between the age of 20 and 50 y, with a female predominance. |

Solitary fibrous tumor | Well-defined, solid mass, isodense to muscle, with heterogeneously or homogeneously strong enhancement and occasional calcification or necrosis. | The buccal space is an uncommon location for this ubiquitous neoplasm. |

Nodular fasciitis | Well-circumscribed, round, solid soft tissue mass in the buccal space, isodense to muscle, with heterogeneously or homogeneously strong contrast enhancement and occasional calcification or necrosis. | Nodular fasciitis is a rare benign proliferation of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts. A history of trauma may precede these mesenchymal tumors. The lesions are generally small and solitary, slowly progressive, commonly seen in the head and neck region of infants and children, and seen in the upper extremities in young adults. |

Malignant neoplasms | ||

Squamous cell carcinoma | Tumors originating in adjacent spaces may extend or secondarily involve the buccal space as aggressive, diffusely infiltrating, fairly enhancing mixed-density mass lesion, with obliteration of the normal fat planes and contrast enhancement of the tumor margins. | Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common malignant tumor involving the buccal space. The tumor may project or extend into the buccal space from deep extension of carcinomas originating in the skin, subcutaneous tissues, buccal mucosa, masticator space, alveolar ridge of the maxilla, retromolar trigone, mandible, base of the tongue, and nasal vestibule. |

Nodal metastases | Metastatic buccal lymphadenopathy typically manifests as a single node > 10 mm in maximum diameter or as a grouping of nodes. Suggestive of nodal metastasis is a round, mildly enhancing soft tissue mass, centered within fat of the anterior or posterior buccal space. Most reliable imaging finding of metastatic disease is the presence of central nodal necrosis. Necrosis appears as central nonenhancing low density with a variably thick, irregular enhancing wall. Ill-defined margins and stranding of surrounding fat are features of extracapsular spread. | Metastatic buccal lymphadenopathy typically occurs in association with clinically evident, deeply infiltrating facial neoplasms, or in recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the sinuses and gingivobuccal sulcus. Patients (> 40 y) present with smooth, nontender, mobile buccal masses. |

Lymphoma | Intranodal lymphoma: Hodgkin and non–Hodgkin lymphomas of buccal nodes can present with multiple or single nodal enlargement as isolated symptom or as part of a systemic disease. Lymph node masses commonly demonstrate homogeneous soft tissue attenuation. In general, there is homogeneous enhancement, although rim enhancement and spotty or dentritic enhancement on CT are sometimes seen. Extranodal lymphoma: Ill-defined and infiltrative buccal space mass along the course of the parotid duct, isolated or associated with nodal disease, extranodal lymphatic disease (Waldeyer ring), and/or involvement of other extranodal extralymphatic sites (e.g., sinus, nose, and orbit). | Buccal space lymphoma may either arise within the buccal lymph nodes or be extranodal. The latter is more common in non–Hodgkin lymphoma and has a poor prognosis. Patients (> 50 y) may have CN V3 symptoms and a buccal space mass as part of systemic non–Hodgkin lymphoma or as the first manifestation of limited head and neck disease. |

Rhabdomyosarcoma | Bulky, heterogeneous, locally invasive, ill-defined soft tissue mass, isodense with muscle, with moderate to marked contrast enhancement. May be heterogeneous due to focal hemorrhage or necrotic areas. Contiguous soft tissues and osseous structures are often involved by direct invasion. | Rhabdomyosarcomas are rare malignant mesenchymal tumors; 40% of these will involve the head and neck. Involvement of the buccal space is uncommon. They tend to occur in children (< 5 y). The most characteristic presenting features are a rapid onset and progression. |

Liposarcoma | Well-differentiated liposarcomas present as a lobulated, fatty mass with some enhancing internal septations or nodules. Calcifications may occur. Less well-differentiated liposarcomas display as heterogeneous, enhancing soft tissue mass with or without amorphous fatty foci, often with unsharp, infiltrating borders. | Only 3 to 6% of liposarcomas occur in the head and neck region. Within the oral cavity, they may be located in the cheek, palate, floor of the mouth, and submental regions. They may occur in all age groups (30–60 y) and show no gender predilection. |

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma | Single mass with hyperattenuating, well-defined or infiltrative margins, central iso- or hypoattenuating area (necrotic), and prominent enhancement. Adjacent malignant adenopathy may be present. | Usually occurs in the accessory parotid gland (exceptionally within Stensen duct). Patients (40–50 y, F = M) present with a nontender, mobile palpable buccal mass that has been present for 1 to 5 y. |

Adenoid cystic carcinoma | Moderate enhancing soft tissue mass with irregular, ill-defined margin or infiltration of surrounding tissues. Differentiation from benign tumors may be difficult, as two thirds of salivary gland malignancies have smooth, well-defined margins. | Adenoid cystic carcinoma is the most frequent malignant tumor of the minor salivary glands (25%). Commonly occurs in women of early middle age. Pain is common. |

Acinic cell carcinoma | Moderate enhancing soft tissue mass with irregular, ill-defined margin or infiltration of surrounding tissues. Differentiation from benign tumors may be difficult, as two thirds of salivary gland malignancies have smooth, well-defined margins. | Twice as common in the accessory parotid gland as in salivary rests. Has a varying biological behavior. Tumor affects women more than men (40–60 y). |

Parotid duct | ||

Sialectasia of Stensen duct | Parotid duct ectasia may present as • Beadlike or rosary-like dilations and stenoses of Stensen duct over the full length • Cystic dilation of the parotid duct. The width of the duct is moderately distended proximal and distal to the cystic area. • Sialectasis with fusiform dilation of the parotid duct | Most commonly due to an obstructed calculus located at the orifice of Stensen duct. With idiopathic parotid duct ectasia, results of the workup for a cause of the duct dilation such as a tumor, inflammation, stricture, or stones are negative. Congenital cystic dilation of the parotid duct with formation of multilocular cystic areas is very rare, may be unilateral or bilateral, and may manifest in infancy or appear later. Painless recurrent tubular swelling over the lateral aspect of the face with an associated intraoral submucosal distention. It sometimes results in recurrent parotitis. |

Trauma | ||

Emphysema | Interstitial radiolucent gaseous collections in the buccal space and in other spaces, including subcutaneous tissues. | Buccal emphysema may occur spontaneously, following trauma or surgery, with pneumoparotitis, or as part of a cervicofacial emphysema. |

Hematoma | Buccal hematoma may appear as soft tissue swelling or as a nonenhancing mass, with hemorrhage and edema of adjacent subcutaneous tissue. In the acute stage, the hematoma may be hyperdense. In the sub-acute stage, the hematoma might be poorly defined and is either isodense or slightly hypodense. When completely liquefied, the hematoma has a homogeneous density that is lower than muscle and may be surrounded by an enhancing pseudocapsule. | Soft tissue hemorrhage can collect as hematoma. Hematomas of the buccal space are a common finding after sports injuries and other blunt head and neck traumas. |

Related posts:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree