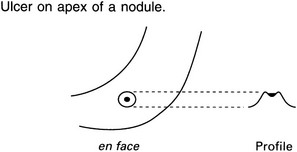

6 6.1 Pneumoperitoneum 1. Plain film (sensitivity 50–70%) (a) Erect – free gas under diaphragm or liver. Can detect 10 ml of gas. Takes 10 minutes for all gas to rise. (b) Supine – gas outlines both sides of bowel wall, which then appears as a white line. The most sensitive signs are in the right upper quadrant (often oval gas over the liver or a hyperlucent liver). In infants a large volume of gas will collect centrally, producing a rounded, relative translucency over the central abdomen. The falciform ligament may also be outlined by free gas. 2. CT (greater sensitivity than plain film) – suspected perforation (a) Focal bowel wall thickening ± discontinuity in bowel wall. (b) Extraluminal +ve oral contrast. (i) Large volume – usually upper gastrointestinal tract, postendoscopy or secondary to obstruction. (ii) Lesser sac – usually gastric or duodenal (rarely oesophagus or transverse colon). (iii) Ligamentum teres – often gastric or duodenal. (iv) Mesenteric folds – usually small bowel or colon (very rarely gastric). (v) Retroperitoneal (duodenum ascending/descending colon, rectum, distal sigmoid). (a) Peptic ulcer – 30% do not have free gas visible. (b) Inflammation – diverticulitis, appendicitis, toxic megacolon, necrotizing enterocolitis. 2. Iatrogenic (surgery, peritoneal dialysis) – may take 3 weeks to reabsorb (faster in obese and children). Free gas may be seen on CT up to 14 days postsurgery. 3. Pneumomediastinum – see 4.30. 4. Introduction per vaginam – e.g. douching. 5. Pneumothorax – due to a congenital pleuroperitoneal fistula. Chiu, Y. H., Chen, J. D., Tiu, C. M., et al. Reappraisal of radiographic signs of pneumoperitoneum at emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 2009; 27(3):320–327. Hainaux, B., Agneessens, E., Bertinotti, R., et al. Accuracy of MDCT in predicting site of gastrointestinal tract perforation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006; 187(5):1179–1183. 6.2 Gasless abdomen 6.3 Pharyngeal/oesophageal pouches and diverticula 1. Zenker’s diverticulum – posteriorly, usually on left side, between the fibres of the inferior constrictor and cricopharyngeus. Can cause dysphagia, regurgitation, aspiration and hoarseness ± an air–fluid level. 2. Lateral pharyngeal pouch and diverticulum – through the unsupported thyrohyoid membrane in the anterolateral wall of the upper hypopharynx. Pouches are common and patients are usually asymptomatic. Diverticula are uncommon and are seen in patients with chronically elevated intrapharyngeal pressure, e.g. glass-blowers and trumpeters. 3. Lateral cervical oesophageal pouch and diverticulum – through the Killian–Jamieson space. Pouches are transient; diverticula are persistent. Patients are usually asymptomatic. The opening is below the level of cricopharyngeus. 1. Traction – at level of carina. May be related to fibrosis after treatment for TB. Asymptomatic. 2. Developmental – failure to complete closure of tracheo-oesophageal communication. 3. Intramural – rare. Multiple, tiny flask-shaped outpouchings. 90% have associated strictures, mainly in the upper third of the oesophagus. 6.4 Oesophageal ulceration In addition to ulceration there may be non-specific signs of oesophagitis: 1. Thickening of longitudinal folds (> 2 mm). 2. Thickening of transverse folds resembling small bowel mucosal folds. 1. Reflux oesophagitis – ± hiatus hernia. Signs characteristic of reflux oesophagitis are: (a) A gastric fundal fold crossing the gastro-oesophageal junction and ending as a polypoid protuberance in the distal oesophagus. (b) Erosions – dots or linear streaks of barium in the distal oesophagus. (c) Ulcers which may be round or, more commonly, linear or serpiginous. 2. Barrett’s oesophagus – to be considered in any patient with oesophageal ulceration or stricture but especially if the abnormality is in the body of the oesophagus (although strictures are more common in the lower oesophagus). Hiatus hernia in 75–90%. Usually endoscopic diagnosis. 3. Candida oesophagitis – predominantly in immunosuppressed patients. Early: small, plaque-like filling defects, often orientated in the long axis of the oesophagus. Advanced: cobblestone mucosal surface ± luminal narrowing. Ulceration is uncommon. Tiny bubbles along the top of the column of barium – the ‘foamy’ oesophagus. Patients with mucocutaneous candidiasis or oesophageal stasis due to achalasia, scleroderma, etc., may develop chronic infection which is characterized by a lacy or reticular appearance of the mucosa ± nodular filling defects. 4. Viral – herpes and CMV occurring mostly in immunocompromised patients. May manifest as discrete ulcers or ulcerated plaques, or mimic Candida oesophagitis. Discrete ulcers on an otherwise normal background mucosa are strongly suggestive of a viral aetiology. 5. Caustic ingestion – ulceration is most marked at the sites of anatomical hold-up and progresses to a long, smooth stricture. 6. Radiotherapy – ulceration is rare. Altered oesophageal motility is frequently the only abnormality. 7. Crohn’s disease* – aphthoid ulcers and, in advanced cases, undermining ulcers, intramural tracking and fistulae. 8. Drug-induced – due to prolonged contact with tetracycline, quinidine and potassium supplements. Canon, C. L., Morgan, D. E., Einstein, D. M., et al. Surgical approach to gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: what the radiologist needs to know. Radiographics. 2005; 25(6):1485–1499. Levine, M. S., Rubesin, S. E. Diseases of the esophagus: diagnosis with esophagography. Radiology. 2005; 237:414–427. 6.5 Oesophageal strictures – smooth 1. Peptic – the stricture develops relatively late. Most frequently at the oesophagogastric junction and associated with reflux and a hiatus hernia. Less commonly, more proximal in the oesophagus and associated with heterotopic gastric mucosa (Barrett’s oesophagus). ± Ulceration. 2. Scleroderma* – reflux through a wide open cardia may produce stricture. Oesophagus is the commonest internal organ to be affected. Peristalsis is poor, cardia wide open and the oesophagus dilated (contains air in the resting state). 3. Corrosives – acute: oedema, spasm, ulceration and loss of mucosal pattern at ‘hold-up’ points (aortic arch and oesophagogastric junction). Strictures are typically long and symmetrical, may take several years to develop and are more likely to be produced by alkalis than acid. 4. Iatrogenic – prolonged use of a nasogastric tube. Stricture in distal oesophagus probably secondary to reflux. Also drugs e.g. bisphosphonates. 1. Carcinoma – squamous carcinoma may infiltrate submucosally. The absence of a hiatus hernia and the presence of an extrinsic soft-tissue mass should differentiate it from a peptic stricture but a carcinoma arising around the cardia may predispose to reflux. 2. Mediastinal tumours – carcinoma of the bronchus and lymph nodes. Localized obstruction ± ulceration and an extrinsic soft-tissue mass. 3. Leiomyoma – narrowing due to a smooth, eccentric, polypoid mass. ± Central ulceration. 6.6 Oesophageal strictures – irregular 1. Carcinoma – increased incidence in achalasia, Plummer–Vinson syndrome, Barrett’s oesophagus, coeliac disease, asbestosis, lye ingestion and tylosis. Mostly squamous carcinomas; adenocarcinoma becoming more common. Appearances include: (a) Irregular filling defect – annular or eccentric. (b) Extraluminal soft-tissue mass on CT or MRI. 3. Carcinosarcoma – big polypoid tumour ± pedunculated. Better prognosis than squamous carcinoma. 6.7 Tertiary contractions in the oesophagus Uncoordinated, non-propulsive contractions 2. Presbyoesophagus – impaired motor function due to muscle atrophy in the elderly. Occurs in 25% of people over 60 years. 3. Obstruction at the cardia – from any cause. 6.8 Stomach masses and filling defects 1. Carcinoma – most polypoidal carcinomas are 1–4 cm in diameter. (Any polyp > 2 cm in diameter must be considered to be malignant). Endoscopic US accurate in local staging for early disease. CT superior for more advanced disease. 2. Lymphoma* – 1–5% of gastric malignancy. Usually non-Hodgkin’s. May be ulcerative, infiltrative and/or polypoid. Often cannot be distinguished from carcinoma, but extension across the pylorus is suggestive of a lymphoma. MALT lymphoma is strongly associated with Helicobacter pylori infection. CT – marked hyopattenuating wall thickening; mean 3–5 cm. Whole stomach involved in 50%. Most (not all) have adjacent lymphadenopathy. 3. GIST – commonest in stomach but also small bowel, colon and mesentery. Variable size and malignant potential. Cell-surface marker (c-KIT) detectable by immunohistochemistry. Large tumours hyperenhancing and often heterogeneous on CT/MRI. Ulceration and fistulation common. 50% have metastasis at presentation (liver, peritoneum). May enlarge with treatment: reduced enhancement suggests response. 1. Hyperplastic – accounts for 80–90% of gastric polyps. Usually multiple, small (< 1 cm in diameter) and occur randomly throughout stomach but predominantly affect body and fundus. Associated with chronic gastritis. Rarely can be very large (3–10 cm). 2. Adenomatous – usually solitary, 1–4 cm in diameter, sessile and occur in antrum. High incidence of malignant transformation, particularly if > 2 cm in size and carcinomas elsewhere in stomach (because of dysplastic epithelium). Associated with pernicious anaemia. 3. Hamartomatous – characteristically multiple, small and relatively spare the antrum. Occur in 30% of Peutz–Jeghers syndrome, 40% of familial polyposis coli and Gardner’s syndrome. Smooth, well-defined filling defect, with a re-entry angle. 1. Leiomyoma – many previously diagnosed would now be classified as GIST. Can be very large with a substantial exogastric component. Central ulceration and massive haematemesis may occur. 2. Lipoma – can change shape with position of patient and may be relatively mobile on palpation. 3. Neurofibroma – NB. Leiomyomas and lipomas are more common, even in patients with generalized neurofibromatosis. 4. Metastases – frequently ulcerate: ‘bull’s-eye’ lesion (q.v.). Usually melanoma, but bronchus, breast, lymphoma, Kaposi’s sarcoma and any adenocarcinoma may metastasize to stomach. Breast primary often produces a scirrhous reaction, indistinguishable from linitis plastica (q.v.). 1. Nissen fundoplication – may mimic a distorted mass in the fundus. 2. Bezoar – ‘mass’ may be mobile. Tricho- (hair) or phyto- (vegetable matter). 3. Lymphoid hyperplasia – innumerable, 1–3 mm diameter, round nodules in the antrum or antrum and body. Association with H. pylori gastritis. 4. Pancreatic ‘rest’– ectopic pancreatic tissue causes a small filling defect, usually on the inferior wall of the antrum, and resembles a submucosal tumour. Central ‘blob’ of barium (‘bull’s-eye’ or target lesion) in 50%. 6.9 Thick stomach folds/wall 1. Gastritis – localized or generalized fold thickening ± inflammatory nodules (< 1 cm, mostly in the antrum), erosions and coarse areae gastricae. 2. Zollinger–Ellison syndrome – suspect if postbulbar ulcers. Ulceration in both first and second parts of duodenum is suggestive, but ulceration distal to this is virtually diagnostic. Thick folds and small bowel dilatation may occur in response to excess acidity. Due to gastrinoma of non-beta cells of pancreas (no calcification, moderately vascular). 50% malignant – metastases to liver. (10% of gastrinomas may be ectopic – usually in medial wall of the duodenum.) 4. Crohn’s disease* – mild thickening of folds with aphthoid ulceration may occur in up to 40% of Crohn’s. 1. Lymphoma* – usually non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, may be primary or secondary. 2. Carcinoma – irregular folds with rigid wall. 3. Pseudolymphoma – benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia. 70% have an ulcer near the centre of the area affected. 1. Ménétrier’s disease – huge, smooth folds, especially greater curve. Rarely extend into antrum. No rigidity or ulcers. ‘Weep’ protein sufficient to cause hypoproteinaemia (effusions, oedema, thick folds in small bowel). Commonly achlorhydric: cf. Zollinger–Ellison syndrome. 2. Varices – occur in fundus and usually associated with oesophageal varices. 6.10 Linitis plastica 1. Corrosives – can cause rigid stricture of antrum extending up to the pylorus. 2. Radiotherapy – can cause rigid stricture of antrum with some deformity. Mucosal folds may be thickened or effaced. Large antral ulcers can also occur. 3. Granulomata – Crohn’s disease, TB. 4. Eosinophilic enteritis – commonly involves gastric antrum (causing narrowing and nodules) in addition to small bowel. Blood eosinophilia. Occasionally spares the mucosa, so needs full-thickness biopsy for confirmation. 6.11 ‘Bull’s-eye’ (target) lesion in the stomach 1. Submucosal metastases – may be multiple 3. Pancreatic ‘rest’ – ectopic pancreatic tissue. Usually on inferior wall of antrum. A central ‘blob’ of barium is seen in 50% – collects in primitive duct remnant. Can also occur in duodenum, jejunum, Meckel’s diverticulum, liver, gallbladder and spleen. 4. Neurofibroma – may be multiple. Other stigmata of neurofibromatosis. 6.13 Duodenal mural/fold thickening or mass 1. Adenocarcinoma – 50–70% of small bowel carcinoma occurs in duodenum or proximal jejunum. Polypoidal mass or asymmetric wall thickening on CT. 50% have metastasis at presentation. 3. Brunner gland hamartoma – 10% of benign duodenal tumours. Usually D1. No malignant potential. 1–12 cm sessile or pedunculated filling defect. 4. Adenoma – malignant potential; associated with familial adenomatous polyposis. 5. GIST – unusual in duodenum; usually D2, D3; large size, heterogeneous rim enhancement and local invasion suggest malignant transformation. 7. Lymphoma – usually non-Hodgkin’s, T cell; CT-segmental non-obstructing mural thickening or extrinsic mass with or without aneurysmal dilatation. 8. Neuroendocrine tumour – 2–3% occur in duodenum; polypoidal or mass with rapid contrast enhancement and washout on CT. 1. Duodenitis/ulcer – usually D1 related to H. pylori. Focal wall thickening and avid enhancement on CT. May see large ulcer cavity. 2. Crohn’s disease – mural thickening on CT/MRI ± layered contrast enhancement. Mild signs occur in duodenum in up to 40%, but severe involvement only occurs in 2%. D1 and D2 predominantly affected. 3. Cystic dystrophy – possible secondary to heterotopic pancreatic tissue in duodenal wall – D2. Presents with weight loss, pain and obstruction. Well-defined duodenal wall cysts on CT/MRI/US scan often with delayed mural enhancement due to fibrosis ± signs of chronic pancreatitis. Inflammatory changes in acute episode. 4. Groove pancreatitis – segmental inflammation between the head of pancreas and duodenum. 6. Diverticulum – up to 23%; may be large. 7. Duplication – less than 5% of intestinal duplications; thin-walled cyst on CT/MRI often with no luminal communication.

Abdomen and gastrointestinal tract

Radiological signs

Causes

Upper third

Middle third

Inflammatory

Inflammatory

Neoplastic

Neoplastic

Primary malignant neoplasms

Polyps

Submucosal neoplasms

Others

Inflammatory

Infiltrative/neoplastic

Others

Inflammatory

Neoplastic

Inflammatory/infiltrative

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Abdomen and gastrointestinal tract