Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm and Dissection

Valerie A. Pomper

Paul D. Campbell Jr.

An abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is defined as a focal widening of the aorta of more than 3 cm in anteroposterior (AP) diameter.

Etiology.

AAAs are most commonly caused by atherosclerosis (73-80%) and result from atrophy and fibrous replacement of the vessel media and adventitia. Other types of aneurysms are uncommon, including mycotic aneurysms (usually associated with intravenous drug abuse (IVDA), steroid therapy, or the immunosuppressed) or traumatic aneurysms. Even rarer are syphilitic aneurysms, which usually affect the ascending aorta and arch.

Location.

Seventy-five percent of AAAs are confined to the abdomen; the remaining 25% also involve the descending thoracic aorta. AAAs occur in an infrarenal position in 95-98% of cases with extension into iliacs in 66% of cases.

Rupture.

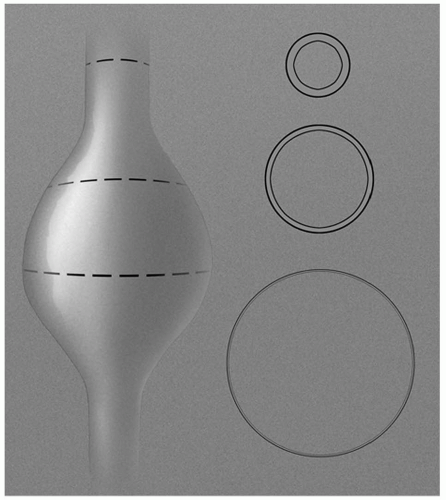

Rupture is the major complication of AAA, and the risk is related to the size of the aneurysm. A small aneurysm (4.5-6 cm) ruptures in 20% of patients over a period of 3 or more years. An aneurysm more than 6 cm ruptures in 50% of patients within 1-2 years (Fig. 25-1).

Symptoms and Signs.

The classic triad (actually seen in only 20% of cases) for a ruptured AAA is as follows:

Central abdominal or back pain.

Pulsatile abdominal mass.

Shock/hypotension.

Note that a prominent abdominal aortic pulsation may be normally present in thin people and be mistakenly diagnosed as an AAA. On the other hand, pulsations from an AAA may not be palpable in patients who are obese. Risk factors for developing atherosclerotic AAA include hypertension, coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, and AAA in a first-degree relative.

Indications.

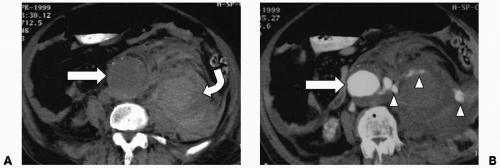

Computed tomography (CT) is the study of choice for evaluating patients for suspected ruptured AAA. Ultrasonography is not indicated for evaluation in emergent settings for several reasons: (1) the ileus that occurs with a ruptured aneurysm is likely to preclude an adequate study, (2) ultrasonography is not as sensitive as CT to diagnose the characteristic perinephric fluid collections, and (3) simply identifying an aneurysm by ultrasonography does not exclude another cause for the patient’s abdominal symptoms. Arteriography does not add to the CT findings and is not necessary, unless it is being performed as a percusor to endovascular therapy.

Protocol.

Scanning the patient without intravenous contrast is useful to detect intramural hematoma. After excluding contraindications to contrast, inject 120 mL of nonionic contrast intravenously at 3 mL/second. Initiate scanning 30 seconds after the start of the injection or use bolus tracking. Depending on the type of CT scanner available choose a slice thickness as low as 0.75 mm, if possible. If imaging both the thorax and abdomen, electrocardiography (ECG)-gated acquisition is preferable in order to eliminate motion artifacts in the ascending aorta, which can mimic aortic dissection. To further reduce the possibility of artifact, the patient’s arms should be placed overhead, and motion should be reduced, as long as these measures are permitted by the patient’s condition. Including the great vessels, thoracic aorta, abdominal aorta, and iliac bifurcation in the aortic protocol is advised. Beware of IV contrast in a hypotensive patient as this can impair renal function. Protocols may vary with different types of CT scanners.

Ruptured Aneurysm

Location.

Rupture may occur into retroperitoneum (commonly on the left side), into the GI tract with massive GI hemorrhage (most commonly the duodenum), or into the inferior vena cava (IVC) with rapid cardiac decompensation.