Fig. 3.1

Normal anatomy of the appendix on barium enema and CT. Coronal CT reformation of the abdomen demonstrates normal air-filled appendix (curved arrow) medial to the cecum. Normal appendiceal caliber is less than 7 mm

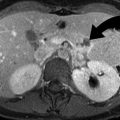

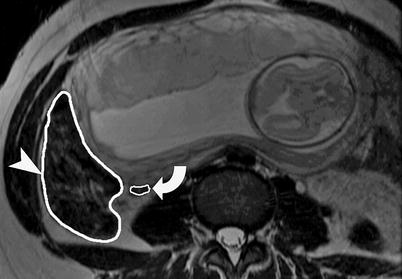

Fig. 3.2

Normal anatomy of appendix on MR imaging. Axial FSE T2-weighted sequence shows normal appendix (arrow) medial to the cecum (arrowhead). The normal appendix is low to intermediate signal intensity on T2-WI and is located between 2 and 6 o’clock position in relation to the cecum

Pathophysiology

Appendicitis is most often due to luminal obstruction followed by bacterial invasion. Appendiceal obstruction can be caused by an appendicolith, foreign body, strictures, lymphoid hyperplasia, or rarely parasitic infections (Fig. 3.3). If obstruction persists, the intraluminal pressure in the appendix may rise above that of the veins, leading to venous obstruction and appendiceal wall ischemia.

Fig. 3.3

Plain radiographic findings of acute appendicitis. (a) Plain x-ray of the abdomen demonstrates a small appendicolith (curved arrow) in the right abdomen. The properitoneal fat pad on the right is obliterated by appendiceal inflammation. The properitoneal fat pad (arrowhead) on the left side is well preserved. The air-containing bowel loops are displaced away from the right lower quadrant. There are changes of paralytic ileus. (b) Plain radiograph of the surgical specimen demonstrates an appendicolith (arrowhead) at the base of the appendix

Pathological Stages of Appendicitis: Three Stages

1.

Acute catarrhal appendicitis: There is early scant neutrophilic infiltrates without perforation. The inflammation of the appendix can spontaneously regress or progress to the second stage.

2.

Purulent (phlegmonous) stage: Neutrophilic infiltrate, ulceration, and necrosis are seen. Spontaneous regression is rare and there is progression to appendiceal perforation.

3.

Gangrenous stage: Necrosis, ulceration, gangrene, and peritoneal inflammation are seen without the possibility of spontaneous regression.

Current Status of US, CT, and MR

Currently, the majority of patients with clinically suspected appendicitis undergo intravenous contrast-enhanced CT with or without oral or rectal contrast before the surgery.

Ultrasound is considered the imaging modality of choice for pediatric and pregnant patients where appendicitis is suspected.

MR is reserved for pregnant patients where US is nondiagnostic or equivocal.

Since the first publications on the utility of CT for appendicitis in the late 1990s, there has been dramatic increase in the use of CT to evaluate right lower quadrant pain. Rao et al. found that CT performed in patients who present with suspected appendicitis improves patient care and reduces the use of hospital cost by resources $447 per patient by avoiding negative laparotomy (Table 3.1) and showed the rate of negative laparotomy decreased from 20 % before to 7 % after the introduction of CT [4, 5].

Table 3.1

Advantages and disadvantages of US and CT

Ultrasound | CT |

|---|---|

1. Relatively inexpensive (technical cost = $50.28) | 1. Higher cost (technical cost = $112.32) [2] |

2. Wide availability | 2. More restricted availability |

3. Can better evaluate pelvic disease in females | 3. Better identifies normal appendix (>85 % in adult and 69 % in children), phlegmon, and abscess [3] |

4. No ionizing radiation (preferred in children and pregnancy) | 4. Ionizing radiation (10 mSv) |

5. Lower sensitivity compared to CT (sensitivity 75–85 %) | 5. More accurate for appendicitis (sensitivity 90–100 %) |

6. Operator dependence and technically inadequate studies due to gas | 6. No operator dependence |

CT Protocol

IV contrast: 370 mg/100 cc at 3.5 mL/s, followed by scanning after 150 s delay.

120 kV; 150 mA; slice thickness – 2.5 mm.

Targeted CT may be used with scanning from L3 to the symphysis pubis.

Reformation (3 mm) in sagittal and coronal planes. The use of coronal reformations improves the confidence of the radiologist in visualizing the appendix and making the diagnosis of acute appendicitis [6].

Oral (2 % barium suspension) vs. rectal (1 L 3 % barium suspension). The use of oral or rectal contrast is considered appropriate by ACR appropriateness criteria in the evaluation of right lower quadrant pain.

The usage of rectal as opposed to oral contrast offers the advantage of reducing the time between ordering of the scan by the physician and the time when it is performed. There is also higher likelihood of opacifying cecum and appendix with contrast. The disadvantages of rectal contrast include increased patient discomfort and the theoretical risk of rupturing the appendix from increased intraluminal pressure in the cecum. In the adult population, the appendix is seen in more than 85 % cases, while in children the visualization rate is lower (69 %) because of the paucity of intra-abdominal fat.

Imaging Findings on CT

1.

Appendiceal caliber: 7 mm or more in width. This criterion alone does not have high positive predictive value because up to 42 % of normal population can have an appendiceal caliber of more than 7 mm.

2.

Appendiceal wall thickness of more than 3 mm.

3.

Appendiceal mural enhancement, homogeneous or stratified appearance of the appendiceal wall (Fig. 3.4 ).

Fig. 3.4

Appendiceal wall changes in acute appendicitis. (a and b) Contrast-enhanced CT in a patient with acute appendicitis shows stratified appendiceal wall thickening (arrowhead). The inner hyperdense ring indicates mucosal enhancement, while the outer hyperdense ring indicates serosal enhancement

4.

Lack of intraluminal contrast in the appendix.

5.

Periappendiceal inflammation.

6.

Appendicoliths (Fig. 3.5): It is seen in 10 % cases on plain radiograph and 30 % on CT study. The detection of an isolated appendicolith on CT is not sufficiently specific to be the sole basis for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis [7]. The use of bone window setting can increase the detection rate of appendicolith [8].

Fig. 3.5

Appendicoliths on CT and plain radiography. (a) Axial contrast-enhanced CT demonstrates grossly dilated appendix (straight arrow), containing multiple appendicoliths (arrowheads). The adjacent pelvic small bowel shows changes of ileus. (b) Plain radiograph of the abdomen demonstrates laminated appendicolith (arrowhead) in the right lower quadrant. Appendicoliths are seen in 10 % cases of appendicitis on plain x-ray of the abdomen

7.

Arrowhead sign: Arrow-shaped configuration of the cecum due to funneling of intraluminal contrast into the spastic cecum (Fig. 3.6). It is an indicator of extension of inflammation from the appendix to the cecum.

Fig. 3.6

Arrowhead sign. Contrast-enhanced CT demonstrates funneling (straight arrow) of contrast in the cecum with the tip pointing towards the base of the inflamed appendix (arrowheads) in an arrowhead configuration. The presence of the arrowhead sign indicates extension of inflammation from the base of the appendix into the cecal wall

8.

Cecal bar sign: It is characterized by edema and bar-like thickening of the cecum at the base of the appendix (Fig. 3.7).

Fig. 3.7

Cecal bar sign. Contrast-enhanced CT demonstrates plaque-like thickening of the cecal wall (straight arrow) adjacent to the base of the inflamed appendix (arrowhead)

9.

Hyperdense appendix: Hyperdense appendix is seen as high-attenuation appendix on noncontrast CT and is seen in 33 % of patients with acute appendicitis [9].

10.

Maximum depth of intraluminal appendiceal fluid of more than 2.6 mm: This can be useful in diagnosis of appendicitis when no periappendiceal inflammation is present [10].

Complications

Appendiceal perforation, abscess, and sepsis are the dreaded complications of acute appendicitis. The frequency of appendiceal perforation is 20–25 %, with the highest frequency in the very young and old (40–70 %). The extension of inflammation outside the appendix can lead to the formation of phlegmon and abscess. The inflammatory adhesions from appendicitis can lead to small bowel obstruction. Acute appendicitis should be in the differential diagnosis whenever there is small bowel obstruction in a patient who has no history of abdominal surgery.

The five specific CT findings of perforated appendicitis are [11] (Figs. 3.8, 3.9, and 3.10):

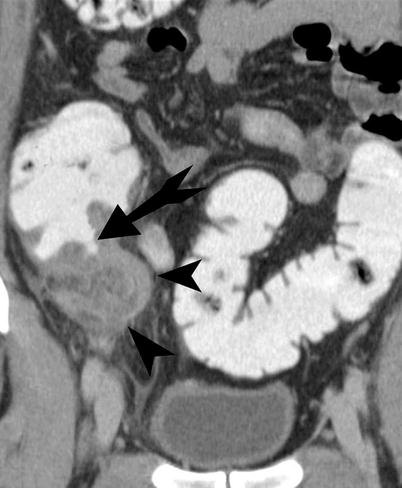

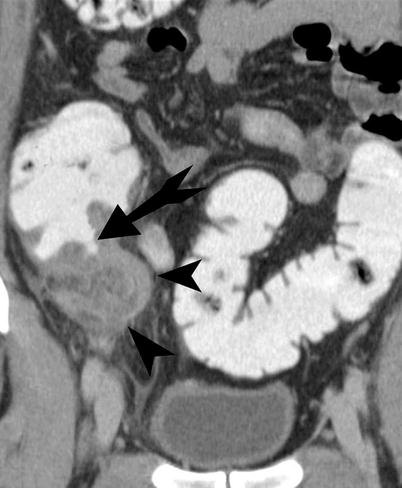

Fig. 3.8

Perforated appendicitis. (a) Contrast-enhanced CT demonstrates abscess (straight arrow) formation in the right lower quadrant from perforated appendicitis. There is an appendicolith (arrowhead) measuring 7 mm in diameter seen within the abscess cavity. (b) Contrast-enhanced CT demonstrates appendiceal perforation by the presence of tiny foci of extraluminal air (arrowhead) in the anterior pelvis. There is extensive inflammation present in the intraperitoneal fat. (c) Contrast-enhanced CT demonstrates appendiceal perforation by discontinuity of the appendiceal wall (arrowhead) on the medial aspect. There is tiny appendicolith seen in the appendix with surrounding inflammation seen in the right lower quadrant. (d) Contrast-enhanced CT demonstrates dilated small bowel loops (arrowheads) in a patient with small bowel obstruction caused secondary to acute appendicitis. (e) Gadolinium-enhanced T1-WI demonstrates a thickened appendiceal wall (arrowhead) to the right side of the uterus with surrounding inflammatory phlegmon

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree