, Sridhar Shankar1 and Ajay Singh2

(1)

Department of Radiology, University of Tennessee, Memphis, TN, USA

(2)

Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, 10 Museum Way, # 524, Boston, MA 02141, USA

Abstract

Each year, more than 120 million patients visit the emergency room in the USA. The single most common cause of presentation in the emergency room patient is abdominal pain. Our job as radiologists is to help pinpoint a diagnosis and triage patients in the right direction. The following review covers acute nontraumatic disease processes of the liver and spleen.

Introduction

Each year, more than 120 million patients visit the emergency room in the USA. The single most common cause of presentation in the emergency room patient is abdominal pain. Our job as radiologists is to help pinpoint a diagnosis and triage patients in the right direction. The following review covers acute nontraumatic disease processes of the liver and spleen.

Acute Hepatitis

Broadly speaking, acute hepatitis is any acute insult to the liver resulting in the influx of inflammatory cells [1]. The differential diagnosis for hepatitis is long, ranging from an acute viral hepatitis to autoimmune hepatitis [2]. The imaging findings of the various causes of hepatitis are relatively nonspecific, and teasing out a specific diagnosis must often be left to the clinician. The imaging findings in acute viral hepatitis are discussed below, though these findings could be seen in any acute hepatitis.

The “classic” ER case of acute hepatitis is one with right upper quadrant pain, jaundice, and fever [2]. In severe cases of fulminant hepatic failure, patients may present with severe coagulopathy and mental status changes [2]. Laboratory evaluation can help determine the diagnosis of hepatitis and possibly a specific cause. The aminotransferases are nearly always elevated, usually significantly so. Viral hepatitis panels help determine if an acute viral infection is the cause. Finally, history is crucial in determining any patient’s risk for hepatitis. Historical factors suggesting acute hepatitis include IV drug use, food poisoning, other autoimmune disease, alcoholism, obesity, diabetes, acetaminophen overdose, or radiation.

Imaging

As mentioned earlier, imaging of acute hepatitis is fairly nonspecific. Ultrasound will often demonstrate hepatomegaly with diffuse decreased echogenicity of the hepatic parenchyma [3]. This decreased echogenicity leads to a relative hyperechoic appearance of the portal branches, resulting in the classic “starry sky” appearance (Fig. 10.1a). There may be associated reactionary gallbladder wall thickening as well. Unfortunately, a normal appearance to the liver does not exclude acute hepatitis [3].

Fig. 10.1

Acute hepatitis C. (a) Ultrasound of the liver shows “starry sky” appearance due to decreased parenchymal echogenicity and relative increase in periportal echogenicity. (b and c) Contrast-enhanced CT demonstrates periportal edema, gallbladder wall edema, and pericholecystic fluid

Contrast-enhanced CT study will often demonstrate a heterogeneous appearing liver [3]. The hypoattenuating regions represent areas of necrosis or periportal edema. The more hyperattenuating regions usually represent focal areas of sparing or, in the more chronic case, areas of nodular regeneration. Other findings include hepatomegaly, periportal edema, gallbladder wall thickening, and ascites (Fig. 10.2b, c). On MRI, T2-weighted images will show hyperintense regions of periportal edema; these same areas will be low intensity on T1 images [3].

Fig. 10.2

Acute hepatitis B. (a) Contrast-enhanced CT demonstrates gallbladder wall edema (arrowhead) and pericholecystic fluid. The gallbladder wall, though prominent, is not as thickened as in the previous case. (b) HIDA scan showing uptake in the gallbladder (curved arrow) and excretion into small bowel loops. The presence of radiotracer into the gallbladder lumen rules out cystic duct

Fulminant hepatitis, the most devastating and life-threatening form, is characterized by a small liver with massive areas of hypoattenuation associated with expansive necrosis [4, 5]. Secondary findings of ascites, splenomegaly, and portal vein dilatation may be noted. Although generally not intended to diagnose hepatitis, HIDA scans in patients with right upper quadrant pain and suspected cholecystitis can be useful in determining the cause of gallbladder wall thickening (Fig. 10.2). Impaired clearance of the blood pool with no excretion of radiotracer into the biliary system suggests marked hepatocellular dysfunction consistent with acute hepatitis.

Hepatic Abscess

Liver abscesses can be polymicrobial, with Escherichia coli being by far the most common pathogen, or they can be due to fungal infection or Entamoeba histolytica. Fungal infection of the liver is most commonly seen in the patient with AIDS, hematologic malignancy, or organ transplant [3]. Candida is the most frequent causative organism. Cryptococcus, histoplasmosis, aspergillus, and mucormycosis are less commonly seen. Liver abscesses are most often caused by spread of biliary infection or by hematogenous spread, superinfection of necrotic liver, or iatrogenic causes. Overall, pyogenic abscesses are a fairly dangerous entity, with an associated 2 % mortality rate [3].

Pyogenic abscesses are generally treated by radiologists, with CT-guided drainage being the mainstay of treatment.

Imaging

Pyogenic Abscess

Pyogenic abscesses can further be subdivided into two categories: microabscesses versus macroabscesses, with 2 cm being the cutoff between the two [3]. Ultrasound and CT are the mainstays of imaging.

In the setting of microabscesses, ultrasound will show a small (<2 cm), possibly scattered hypoechoic focus or foci, or heterogeneous echotexture. With macroabscesses, the ultrasound appearance can be quite varied, ranging from hypoechoic to hyperechoic with varying degrees of internal septation and debris. Internal gas, indicated by high-intensity echoes and dirty posterior shadowing, helps seal the diagnosis [3].

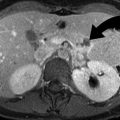

CT, with microabscesses, will demonstrate small, hypoattenuating lesions with faint peripheral enhancement and surrounding edema [3]. Larger abscesses will also be hypoattenuating, often with irregular margins, rim enhancement, and internal gas (Figs. 10.3 and 10.4).

Fig. 10.3

Pyogenic hepatic abscess after liver transplant. (a) Contrast-enhanced CT through the liver demonstrates a large, irregular hypodense collection (arrow) in the left lobe of liver, containing air. This is virtually diagnostic of an abscess. An internal biliary stent is also seen. (b) Gray-scale ultrasound in the same patient showing a complex collection (arrow) within the liver. This patient went on to have percutaneous drainage of the abscess under CT guidance

Fig. 10.4

Hepatic abscess. (a) Plain film of the upper abdomen demonstrates a round collection of gas in the right upper quadrant (curved arrow). This would be an atypical appearance and location of bowel gas. (b) Contrast-enhanced CT through the upper abdomen confirms a large collection of air within the liver with some layering debris (curved arrow), diagnostic of abscess

Fungal Abscess

At ultrasound four appearances of fungal infection have been described:

1.

A “wheel within a wheel” appearance featuring a central hypoechoic zone of fungal necrosis surrounded by echogenic inflammatory cells. There may also be a thin hypoechoic rim of fibrosis.

2.

A “bull’s-eye” appearance with a central echogenic Nidus with a surrounding hypoechoic region. This appearance is seen in patients with active infection.

3.

Simply a hypoechoic nodule without other distinguishing features. Unfortunately, this is the most common appearance and also the least specific.

4.

An echogenic focus with posterior shadowing. This appearance is typically seen during early resolution.

At contrast-enhanced CT, the typical finding is multiple, small, hypoattenuating lesions throughout the liver. The lesions typically enhance centrally (though less than the surrounding liver) and may occasionally enhance peripherally. MRI will demonstrate multiple small lesions throughout the liver which are extremely T2 hyperintense and mildly hypointense on T1-weighted images (Fig. 10.5). Gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted images will show hypointense lesions when compared to the surrounding liver.

Fig. 10.5

Hepatic abscesses. (a) Transverse and sagittal gray-scale ultrasound images of the liver demonstrate a hypoechoic lesion with a hyperechoic rim (white arrowhead). (b) Gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted MRI in the same patient shows a necrotic lesion (black arrowhead) in the right lobe of the liver with faint peripheral enhancement. This is a case of treated enterococcal abscess. (c) Contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen shows a fluid density lesion with an irregular wall, consistent with abscess (curved arrow). Incidentally note is made of a hemangioma, located more anteriorly in the right lobe of liver. (d) Contrast-enhanced CT abdomen through the inferior aspect of the liver demonstrates an irregular abscess (arrow), communicating with pyonephrosis (arrowhead)

Amebic Abscess

Although amebic abscesses may appear very similar to pyogenic abscesses, one helpful clue is the tendency for amebic abscesses to spread beyond the liver. Findings of a right pleural effusion or intraperitoneal rupture suggest the diagnosis of amebic abscess [6].

Amebic abscesses are typically oval abscesses seen near the capsule, generally hypoechoic on ultrasound, with low level internal echoes and no wall echoes. There may be increased through transmission. Contrast-enhanced CT will show a complex fluid collection with rim enhancement and peripheral edema. Internal septa or fluid-debris levels may be identified [3, 6]. MRI, if utilized, will generally show a high-intensity T2 lesion with low intensity on T1. Fifty percent will have surrounding edema, best appreciated on the T2 sequence [3].

Hydatid Cyst

Though rarely seen in the USA, hydatid cysts are endemic to the Mediterranean Basin. The disease is spread through ingesting the eggs of Echinococcus granulosus, a tapeworm. Dogs act as a reservoir for the spread of disease. Hydatid cysts often go undetected, but patients may present secondary to cyst rupture, mass effect of the cyst, or superimposed infection [2].

Histologically, hydatid cysts consist of three layers. The outer pericyst is composed of compressed liver; the middle ectocyst, a thin membrane; and the inner endocyst, a germinal layer [3].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree