Adenomyosis is a common condition characterized by the presence of heterotopic endometrial tissue within the myometrium. The condition is most commonly found in multiparous women between the ages of 35 and 50 years, may be asymptomatic, or may cause dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia. Adenomyosis may involve the uterus focally or, more commonly, diffusely. Clinical diagnosis is difficult because of the frequent overlap of symptoms with other uterine pathology, particularly fibroid disease. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the definitive imaging modality for noninvasive diagnosis.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of adenomyosis in asymptomatic women ranges from 10% to 60%. The true prevalence is difficult to ascertain, given that the prevalence from hysterectomy specimens varies widely depending on pathologic criteria and source. The pathogenesis of adenomyosis is unknown but is theorized to be associated with disruption of the barrier between the endometrium and myometrium as an initiating step. Risk factors include increased parity, uterine surgeries, and uterine trauma.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

In 1972, Bird et al. defined adenomyosis as benign invasion of endometrium into the myometrium. This definition has been further refined as the presence of endometrial glands and stroma inordinately deep within the myometrium. The endomyometrial junction is typically irregular, and minimal adenomyosis has to be distinguished from the basalis layer that may appear surrounded by myometrium as a result of tangential cutting of the specimen. In obvious cases of adenomyosis, the histologic diagnosis is straightforward because the endometrial glands and stroma are deep within the myometrium. A helpful characteristic finding in the premenopausal uterus is the presence of smooth muscle hypertrophy surrounding foci of endometrial glands. Smooth muscle hypertrophy, however, is less apparent in the postmenopausal and gravid uterus. A depth requirement can be used as well. On microscopic examination, irregular nests of endometrial stroma, with or without glands, are arranged within the myometrium, separated from the basalis by at least 2.5 mm. In the premenopausal uterus, the diagnosis should be made only if there is associated smooth muscle hypertrophy.

It is smooth muscle hypertrophy that causes the typical gross appearance of an enlarged, globular uterus. When adenomyosis is focal, the gross appearance may be confused with a leiomyoma. The term adenomyoma has been used to describe this finding, but focal adenomyosis is the preferred term. Focal adenomyosis more frequently involves the posterior uterine wall.

The ectopic endometrial glands are usually the basalis type, which do not undergo the cyclic changes of the menstrual cycle. This is in contradistinction to endometriosis, which is the functionalis layer outside the uterus that is hormonally responsive and thus undergoes hemorrhage. Rarely hemorrhage or hemosiderin-laden macrophages can be seen in the heterotopic stroma within the myometrium. Secretory changes in the glands and stromal decidualization frequently occur in pregnancy and during progestin therapy.

The etiology of adenomyosis is unknown. A popular theory is that it develops as a result of downgrowth and invagination of the basalis endometrium into the myometrium. Adenomyosis is rarely an isolated finding. It is commonly associated with leiomyomata (57%), endometriosis (28%), endometrial hyperplasia (3.5%), and uterine cancer. One study showed that 60% of uteri with endometrial carcinoma contained coexisting adenomyosis compared with 39% of the controls. Prolonged estrogen exposure may play a role in the pathogenesis of these disorders. Long-term tamoxifen therapy in postmenopausal women can reactivate adenomyosis.

Clinical Presentation

A significant fraction of women with adenomyosis are asymptomatic. The most frequent symptoms are menorrhagia, metrorrhagia, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and chronic pelvic pain. Pelvic examination can reveal an enlarged, tender uterus. The frequency and severity of symptoms correlate with the extent and depth of adenomyosis. Infertility is less common because adenomyosis is usually diagnosed later in reproductive years; however, no large studies examining the impact of adenomyosis on fertility have been conducted. Clinically adenomyosis is underdiagnosed. In one study the diagnosis was suspected preoperatively in 10% of women, and at surgery adenomyosis was identified in 65% of patients. The lack of characteristic symptoms and association with more obvious pelvic pathology have likely resulted in underdiagnosis.

Imaging

The advent of MRI has markedly improved the accuracy of diagnosis. Although transvaginal sonography is typically the first screening modality in a woman with pelvic pain and abnormal bleeding, the consensus is that MRI is significantly better than ultrasound (US) in the diagnosis of adenomyosis.

Sonography

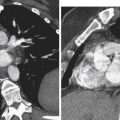

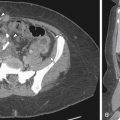

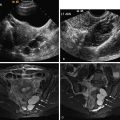

US technique is highly operator dependent, and the sonographic signs of adenomyosis can be subtle. The presence of myomas can limit the evaluation of the adjacent myometrium, whereas MRI is not affected by concomitant disease. Sonographic findings suggestive of adenomyosis include heterogeneous enlargement of the uterus, asymmetric thickening of the myometrium ( Figure 14-1 ), presence of myometrial cysts ( Figure 14-2 ), echogenic striations ( see Figures 14-3, 14-6, C , and 14-8 , C and D ), and an indistinct endometrial–myometrial junction. Overall sensitivity and specificity of transvaginal sonography range from 65% to 89% and 67% to 98%. Sonohysterography findings also include myometrial cracks: ill-defined areas of fluid intravasation extending from the endometrial cavity into the myometrium.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI provides superior soft tissue contrast resolution in the evaluation of the uterus and adjoining structures and currently represents the most accurate technique for the noninvasive diagnosis of adenomyosis and other uterine pathology. MRI can be used for screening and problem solving. Overall sensitivity and specificity of MRI range from 77% to 89% and 89% to 93%.

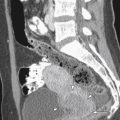

MRI is accurate in depicting normal uterine anatomy and a variety of pathologies. T2-weighted images are the most valuable because the zonal anatomy of the uterus is optimally demonstrated. Endometrial fluid, endometrium, junctional zone (JZ) myometrium, outer myometrium, and the surrounding tissues can be readily differentiated ( Figure 14-4 ).

The most common imaging finding of adenomyosis is thickening of the JZ, the inner layer of the myometrium. Compared with the outer myometrial layer, the JZ myocytes are characterized by higher cellular density and higher nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio. These structural differences allow differentiation of the myometrial zonal anatomy by T2-weighted MRI. Low signal intensity JZ myometrium surrounds the high signal intensity endometrium, and is in turn surrounded by intermediate signal intensity outer myometrium.

Reinhold et al. correlated the thickness of the JZ with histopathologic evaluation. Using a threshold value of JZ thickness of 12 mm or more, adenomyosis was diagnosed with a sensitivity of 93%, specificity of 91%, positive predictive value of 79%, and negative predictive value of 98%. In patients with JZ thickness of 8 to 11 mm, secondary findings of high signal foci on T2- or T1-weighted images, focal thickening of the JZ, poor border definition, and linear high signal myometrial striations can be used to diagnose adenomyosis. Brown et al. reported the lowest values for JZ thickness in healthy women taking oral contraceptives (mean JZ thickness, 4.95 ± 1.77 mm) and the highest values in women with irregular menstrual cycles (mean JZ thickness, 8.00 ± 1.18 mm). Uterine zonal differentiation depends on gonadal hormones. Zonal anatomy can be indistinct in premenopausal and postmenopausal women, reappears in postmenopausal women taking hormone supplementation, and varies throughout the menstrual cycle. The JZ thickness increases by 2 mm between days 8 and 16.

Adenomyosis most commonly appears on imaging as diffuse ( Figure 14-5 ) or focal ( Figure 14-6 ) thickening of the JZ. Foci of high signal on T2-weighted images within the myometrium correspond to ectopic endometrial tissue and cystic gland dilatation ( Figure 14-7 ). Ovoid foci are more common. Linear high signal striations on T2-weighted images ( Figure 14-8 ) can also be seen in adenomyosis and represent the infiltrated heterotopic glands. Occasionally foci of hemorrhage can be seen on T1-weighted images ( Figure 14-9 ). These are typically less than 5 mm and are uncommon because adenomyosis, being composed of the stratum basale, is not typically hormonally responsive (as is the stratum functionale in endometriosis).