CHAPTER TWO Airway

It has been said that one of the differentiating features between a pediatric and a general radiologist is that a pediatric radiologist remembers to look at the airway. Problems with the airway are much more common in children than in adults. For practical purposes, abnormalities of the airway can be divided into acute upper airway obstruction, lower airway obstruction (extrinsic compression, intrinsic obstruction), obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and congenital high airway obstruction syndrome (CHAOS).

ACUTE UPPER AIRWAY OBSTRUCTION

Croup

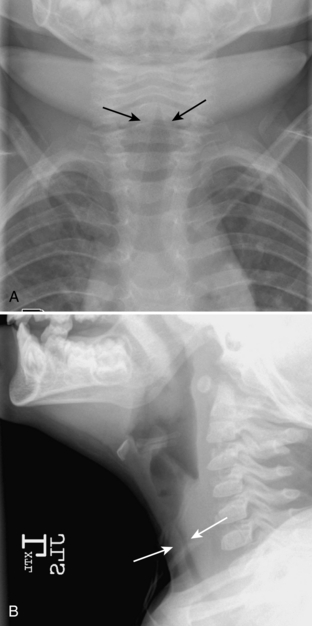

The purpose of obtaining radiographs in a patient with suspected croup is not to document the diagnosis but rather to exclude other, more serious, causes of upper airway obstruction that require intervention. However, characteristic radiographic findings that indicate croup are best seen on frontal radiographs. With croup, there is loss of the normal shoulders (lateral convexities) of the subglottic trachea secondary to symmetric subglottic edema (Fig. 2-1A, B). Normally, the subglottic trachea appears rounded, with “shoulders” that are convex outward (Fig 2-2). In croup, the subglottic trachea becomes long and thin, with the narrow portion extending more inferiorly than the level of the pyriform sinuses. The appearance has been likened to an inverted V or a church steeple (see Fig. 2-1). I have found the term church steeple confusing because some steeples look like croup and some are shaped like the normal subglottic airway (Fig. 2-3). Lateral radiographs may demonstrate a narrowing or loss of definition of the lumen of the subglottic trachea (see Fig. 2-1) or hypopharyngeal overdistention. The epiglottis and aryepiglottic folds appear normal.

Epiglottitis

In contrast to croup, epiglottitis is a life-threatening disease that could potentially require emergent intubation. The possibility that a child with epiglottitis might arrive in a deserted radiology department was once a constant source of anxiety for on-call radiology residents. However, most cases of epiglottitis are caused by Hemophilus influenzae and are now preventable by immunization (HiB vaccine), so the incidence of epiglottitis has dramatically decreased. I think caregivers should be more nervous about epiglottitis now because health care workers are less used to dealing with patients with this disorder. Children with epiglottitis are usually toxic appearing and present with an abrupt onset of stridor, dysphagia, fever, restlessness, and an increase in respiratory distress when recumbent. The patients are typically older than those with croup; the classically described peak incidence occurs at age 3.5 years. However, since the introduction of the HiB vaccine, some reports have shown a marked increase in the mean age of presentation to 14.6 years. Because of the risk for complete airway obstruction and respiratory failure, no maneuvers should be performed that make the patient uncomfortable. If the diagnosis is not made on physical examination, a single lateral radiograph of the neck should be obtained, usually with the patient erect or in whatever position that allows the patient to breathe comfortably. Children with epiglottitis should never be made to lie supine against their will in order to obtain a radiograph because it can result in acute airway obstruction and, potentially, death.

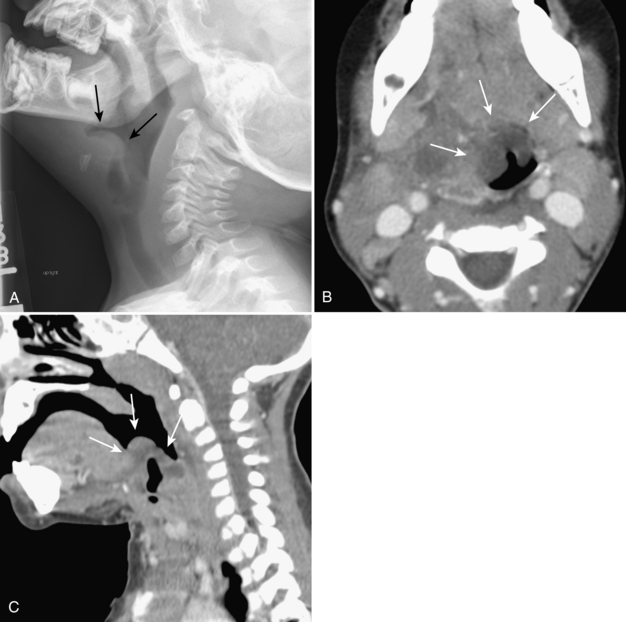

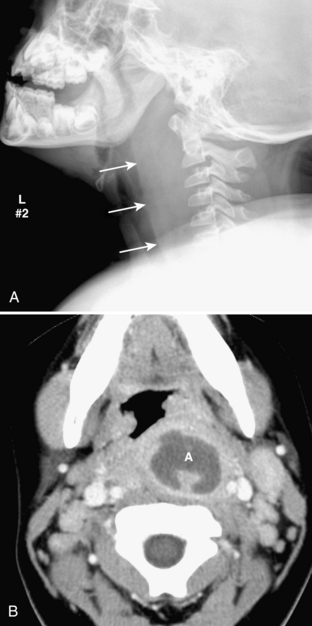

On the lateral radiograph, there is marked enlargement of epiglottis. The swollen epiglottis has been likened to the appearance of a thumb. There is also thickening of the aryepiglottic folds (Fig. 2-4A-C). The aryepiglottic folds are the soft tissues that extend from the epiglottis anterosuperiorly to the arytenoid cartilage posteroinferiorly and normally are convex downward. When the aryepiglottic folds become abnormally thickened, they appear convex superiorly. An obliquely imaged, or so-called omega-shaped, epiglottis may artifactually appear wide because both the left and right sides of the epiglottis are being imaged adjacent to each other. This should not be confused with a truly enlarged epiglottis. The presence or absence of thickening of the aryepiglottic folds can be helpful in making this differentiation. On lateral view, a normal epiglottis has a very thick appearance. Often both the left and right walls of the epiglottis are visible (Fig. 2-5). Symmetric subglottic narrowing, similar to croup, may be seen on frontal radiography (if obtained); do not let that confuse you.

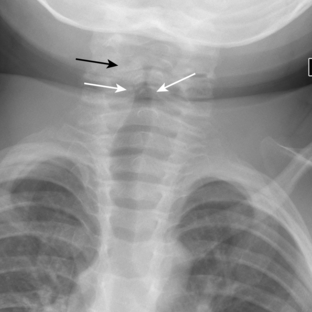

Exudative Tracheitis

Exudative tracheitis (also know as bacterial tracheitis, membranous croup, or membranous laryngotracheobronchitis) is another uncommon but potentially life-threatening cause of acute upper airway obstruction. The disorder is characterized by a purulent infection of the trachea in which exudative plaques form along the tracheal walls (much like those seen in diphtheria). Affected children are usually older and more ill than those with standard croup; typically their ages range from 6 to 10 years. Although initial reports described most cases to be secondary to infection by Staphylococcus aureus, other reports have noted multimicrobial infections. It is unclear whether the disease is a primary bacterial infection or a secondary bacterial infection that occurs following damage to the respiratory mucosa by a viral infection. A linear soft tissue filling defect (a membrane) seen within the airway on radiography is the most characteristic finding. A plaquelike irregularity of the tracheal wall is also highly suspicious (Fig. 2-6). Nonadherent mucus may mimic a membrane radiographically. In cooperative patients, having them cough and then repeating the film may help to differentiate mucus from a membrane. Other findings include symmetric or asymmetric subglottic narrowing in a child too old typically to have croup and irregularity or loss of definition of the tracheal wall. Membranes and tracheal wall irregularities may be seen on frontal or lateral radiographs, and often seen on one but not the other, so it is therefore important to get both views.

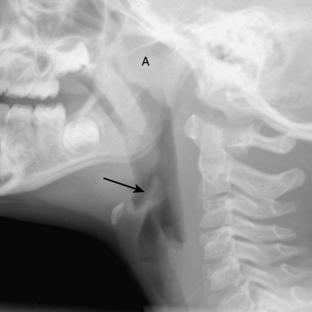

Retropharyngeal Cellulitis and Abscess

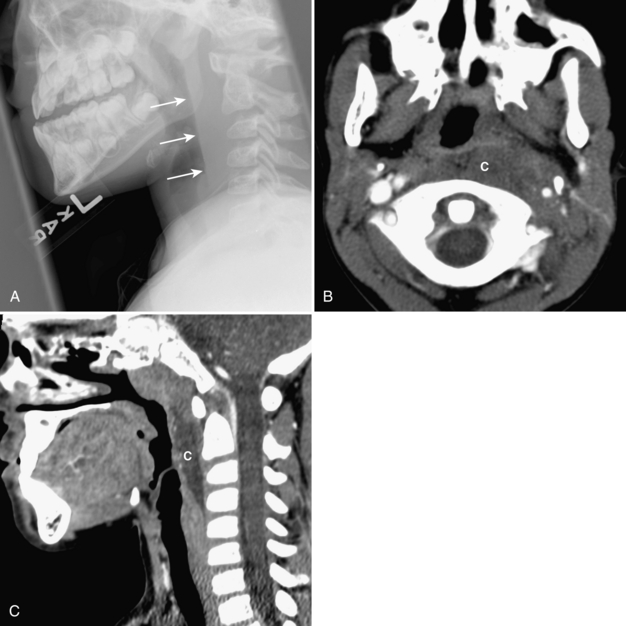

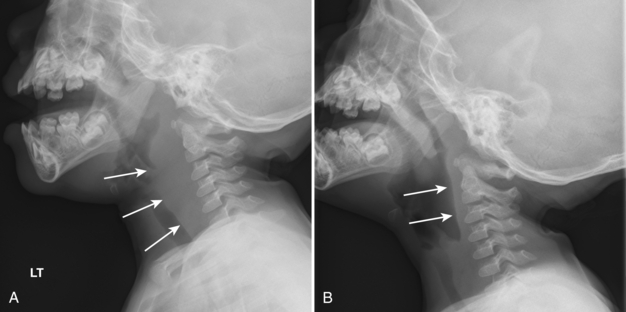

Retropharyngeal cellulitis is a pyogenic infection of the retropharyngeal space that usually follows a recent pharyngitis or upper respiratory tract infection. Children present with sudden onset of fever, stiff neck, dysphagia, and occasionally stridor. Most affected children are young, with more than half of the cases occurring between 6 and 12 months of age. On lateral radiography, there is thickening of the retropharyngeal soft tissues (Figs. 2-7A, B, 2-8A-C). In an infant or young child, the soft tissues between the posterior aspect of the aerated pharynx and the anterior aspect of the vertebral column should not exceed the anterior to posterior diameter of the cervical vertebral bodies. However, in infants, who have short necks, it is common to see pseudothickening of the retropharyngeal soft tissues when the lateral radiograph is obtained without the neck’s being well-extended (Fig. 2-9A, B). Apex anterior convexity of the retropharyngeal soft tissues provides supportive evidence that there is true widening of the retropharyngeal soft tissues (see Fig. 2-7). If it is unclear on the initial lateral radiograph whether the soft tissues are truly versus artifactually widened, it is best to repeat the lateral radiograph with the neck placed in full extension (see Fig. 2-9). The only radiographic feature that can differentiate abscess from cellulitis is the identification of gas within the retropharyngeal soft tissues. Computed tomography (CT) is commonly performed to define the extent of disease and to help predict cases in which a drainable fluid collection is present (see Figs. 2-7, 2-8). On CT, a low-attenuation, well-defined area with an enhancing rim is suspicious for a drainable fluid collection (see Fig. 2-7). Cellulitis without abscess (see Fig. 2-8) is actually more common than a drainable abscess.