CHAPTER SIX Genitourinary

URINARY TRACT INFECTIONS

Urinary tract infection (UTI) is the most common problem of the genitourinary system encountered in children. The urinary tract is the second most common site of infection in children overall, with the upper respiratory tract being the first. The incidence of UTI is higher in girls than in boys, probably because of the short length of the female urethra. There is some current controversy concerning when children with UTIs should be imaged. Most physicians would agree that boys should be studied after the first UTI and that girls should be studied after the second UTI. However, there are some physicians who advocate that all children should be imaged after the first UTI. The immediate goals of imaging children with UTIs include identifying underlying congenital anomalies that predispose the child to UTI, identifying vesicoureteral reflux, identifying and documenting any renal cortical damage, providing a baseline renal size for subsequent evaluation of renal growth, and establishing prognostic factors. The long-term goal is to eliminate the chance of renal damage leading to chronic renal disease and hypertension.

Renal Ultrasound

The kidneys of infants have several characteristics that are different from those of older children and adults. They commonly have a prominent undulating contour. This is a normal appearance secondary to fetal lobulation (Fig. 6-1). In addition, infants’ kidneys can demonstrate prominent hypoechoic renal pyramids (see Fig. 6-1) in contrast to the more echogenic renal cortex. These findings should not be mistaken for hydronephrosis.

Fluoroscopic Voiding Cystourethrogram

The most common indication for a fluoroscopic voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) is the evaluation of UTI. Other indications include voiding dysfunction, enuresis, and the workup for hydronephrosis. The VCUG demonstrates the presence or absence of vesicoureteral reflux and also documents anatomic abnormalities of the bladder and urethra. Because catheterization is used for the procedure, there can be a great deal of anxiety for both the patient and the parents. Education of the parents and patient prior to the examination is crucial to optimizing the patient’s experience. VCUGs are performed under fluoroscopy with the patient awake. The patient is catheterized under sterile conditions on the fluoroscopy table, typically using an 8F catheter. A precontrast scout view of the abdomen is usually obtained to evaluate for calcifications, to document the bowel pattern so that it is not later mistaken for vesicoureteral reflux, and to document the catheter position within the bladder. Contrast is then instilled into the bladder. An early filling view of the bladder should be obtained to exclude a ureterocele. A ureterocele appears as a round, well-defined filling defect on early filling views. On later full views of the bladder, a ureterocele can be compressed and obscured. Once the patient’s bladder is full, bilateral oblique views are obtained to visualize the regions of the ureteral vesicular junctions. These views are typically obtained with the collimators open from top to bottom, with the bladder positioned at the inferior aspect of the screen and the expected path of the ureter included on the film. During voiding, the male urethra is optimally imaged with the patient in the oblique projection. The female urethra is best seen on the anteroposterior view. It is critical to obtain an image of the urethra during voiding, particularly in males. In order to ensure that a view of the urethra is obtained, an image should be obtained during urination with the catheter in place and then a second view can be obtained after the catheter has been removed. After the patient has completed voiding, images are obtained of the pelvis and over the kidneys, documenting the presence or absence of vesicoureteral reflux and evaluating the extent of postvoid residual contrast within the bladder. The use of fluoroscopy should be brief and intermittent during bladder filling. Fluoroscopic last-image hold images can often substitute for true exposures in order to further decrease radiation dose.

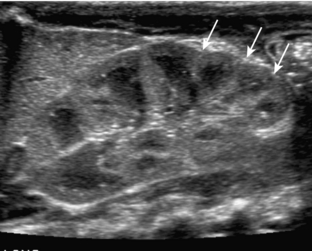

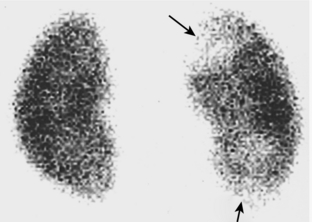

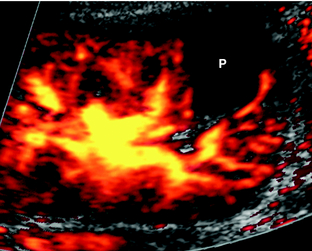

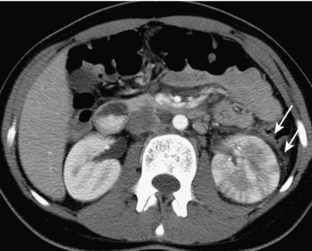

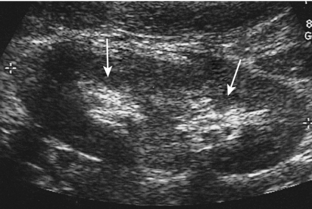

Acute Pyelonephritis

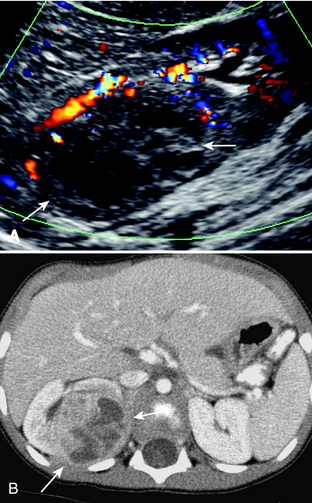

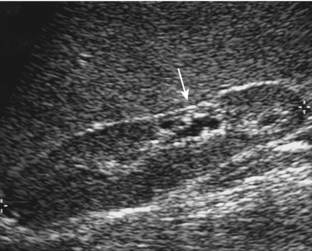

There is some confusion concerning the terminology used for infections of the urinary tract in children. The definition of UTI is the presence of bacteria in the urine, but the term typically refers to infections of the lower urinary tract. Acute pyelonephritis is defined as urinary tract infection that involves the kidney. Young children may present with nonspecific symptoms, such as fever, irritability, and vague abdominal pain. In older children, the findings may be more specific, such as fever associated with flank pain. In patients in whom the diagnosis is straightforward, no imaging is needed during the acute infection, but the patients are imaged later as the standard workup for UTI. In patients in whom there is clinical difficulty in distinguishing an upper from a lower UTI, cortical scintigraphy using dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) has been advocated as being the most sensitive test. In the case of pyelonephritis, this study demonstrates single or multiple areas of lack of renal uptake of the radiotracer. These areas tend to be triangular and peripheral (Fig. 6-2). Other imaging studies that have also been advocated to detect acute pyelonephritis include color Doppler ultrasound and contrast-enhanced helical computed tomography (CT). These studies typically demonstrate lack of color flow or contrast enhancement of triangular, peripheral portions of the kidney (Fig. 6-3). CT may show a striated nephrogram (Fig. 6-4). Also, pyelonephritis can be very focal and can mimic a mass on all of these studies (Fig. 6-5A, B). Ultrasound and CT may also demonstrate disproportionate enlargement and swelling of the affected kidney as compared to the contralateral side. Sometimes the findings of pyelonephritis will be encountered on these imaging studies when the studies were obtained for other suspected causes of abdominal pain such as appendicitis.

Chronic Pyelonephritis

Chronic pyelonephritis is defined as the loss of renal parenchyma resulting from previous bacterial infection. It is synonymous with renal scarring. Normally, the renal cortical thickness should be symmetric and equal within the upper, mid, and lower poles of the kidneys. The loss of renal cortical substance as seen by ultrasound, most commonly at one of the renal poles, is suggestive of the diagnosis (Fig. 6-6). This should not be confused with fetal lobulation (also known as an interrenicular septum; Fig. 6-7A, B), a normal variant. In pyelonephrotic scarring, the indentations of the renal contour tend to overlie the renal calyces, whereas in fetal lobulation, the indentations are between renal calyces (see Fig. 6-7).

EVALUATION OF PRENATALLY DIAGNOSED HYDRONEPHROSIS

As a result of the increasing use of prenatal ultrasound, pediatric radiologists are more frequently having to perform postnatal workups of prenatally diagnosed hydronephrosis. The evaluation of such patients typically includes both ultrasound and VCUG. The controversy revolves around the timing of the ultrasound evaluation. In neonates, there is a relative state of dehydration that occurs after the first 24 hours of life. Reports have shown that this relative state of dehydration can lead to underestimation or nondetection of hydronephrosis by ultrasound. Therefore, it is recommended that the postnatal evaluation of prenatally diagnosed hydronephrosis be performed during the first 24 hours of life or after 1 week of age. The disadvantage of doing the ultrasound during the first 24 hours of life is the interruption of mother-child bonding, whereas the disadvantage of performing the examination at 7 days of life is the potential of parental noncompliance and losing the patient for follow-up.

Vesicoureteral Reflux

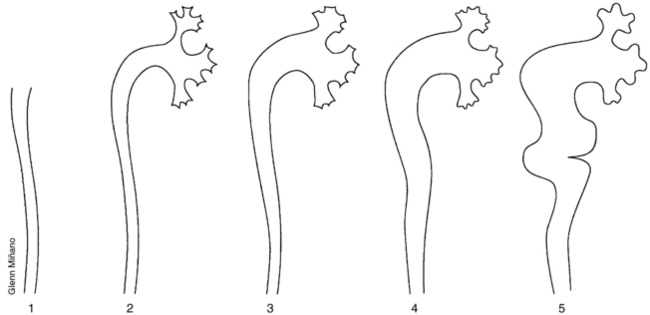

Vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) is defined as retrograde flow of urine from the bladder into the ureter. It is thought to be a primary abnormality related to immaturity or maldevelopment of the ureterovesicular junction. Normally, the ureter enters the ureterovesicular junction in an oblique manner such that the intramural ureter traverses the bladder wall for an adequate length to create a passive antireflux valve. When the angle of entrance of the ureter is abnormal, vesicoureteral reflux results. VUR occurs in less than 0.5% of asymptomatic children but is present in as much as 50% of children with UTIs. There is an increased incidence of VUR in siblings of children with VUR, in children of parents who had VUR, and in non-blacks as compared to blacks. The importance of VUR is its association with renal parenchymal scarring. VUR is present in almost all children with severe renal scarring. Also, a direct correlation between the grade of VUR and the prevalence of scarring has been demonstrated. Other complications associated with VUR include acute pyelonephritis, interference with the normal growth of the kidney, and development of hypertension. The degree of VUR is graded on the basis of several characteristics (Fig. 6-8): the level to which the reflux occurs (ureteral vs. ureteral and collecting system); the degree of dilatation; the calyceal blunting; and papillary impressions. Grade 1 reflux is confined to the ureter. Grade 2 reflux fills the ureter and collecting system, but there is no dilatation of the collecting system. Grade 3 reflux is associated with blunting of the calyces. In deciding whether a calyx is dilatated or not, I was taught that if it looks like you could pick your teeth with a calyx, it is not dilatated (Fig. 6-9). Grade 4 reflux is identified by progressive, tortuous dilatation of the renal collecting system. Grade 5 reflux is defined by the presence of a very tortuous dilatated ureter. Both grade 4 and grade 5 reflux can be associated with intrarenal reflux. It is surprising, but significant VUR can be present in spite of a normal renal ultrasound. Lack of dilatation on ultrasound in no way excludes the presence of VUR. Dilatation of the ureter or collecting systems can sometimes be seen intermittently when VUR is present.

Most low-grade VUR resolves spontaneously by the age of 5 to 6 years unless there is an underlying anatomic abnormality. In children without anatomic reasons that prohibit spontaneous resolution of reflux, most are treated with prophylactic antibiotics alone. Antibiotic therapy is discontinued when the reflux has resolved. Surgical reimplantation of the ureter or periureteral injection (minimally invasive endoscopic treatment) is considered when the degree of VUR is severe, if there is evidence of renal scarring, if the VUR has not resolved over a reasonable time, or if break-through infections occur frequently. After periureteral injection, ultrasound will show an echogenic mound in the bladder wall in the region of the treated ureteral orifice (Fig. 6-10).

Ureteropelvic Junction Obstruction

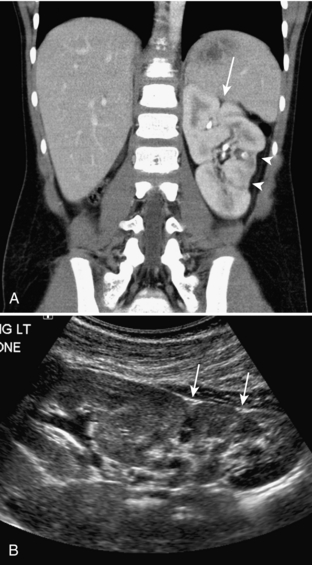

Ureteropelvic junction (UPJ) obstruction is defined as an obstruction of the flow of urine from the renal pelvis into the proximal ureter. It is the most common congenital obstruction of the urinary tract. There is an increased incidence of other congenital anomalies of the urinary tract in patients with UPJ obstruction. They include vesicoureteral reflux, renal duplication, and ureterovesicular junction obstruction. In addition, UPJ obstruction may be present bilaterally but the severity may be asymmetric. The cause of most UPJ obstructions is intrinsic narrowing at the UPJ. However, extrinsic compression secondary to anomalous vessels is also occasionally identified. On ultrasound, there is dilatation of the renal collecting system without dilatation of the ureter (Fig. 6-11). The degree of dilatation may be severe. Renal scintigraphy using 99m technetium-MAG3 with diuretic (furosemide) challenge is often used to evaluate the severity of the UPJ obstruction. Children with UPJ obstruction and other congenital anomalies are predisposed to renal injury even by minor abdominal trauma (Fig. 6-12). Mild to moderate UPJ obstructions are sometimes treated conservatively, but most urologists treat severe UPJ obstruction surgically.

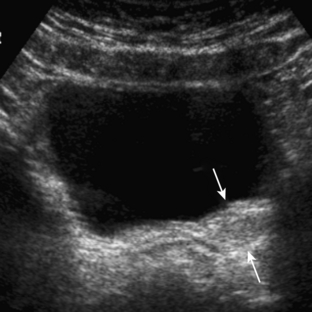

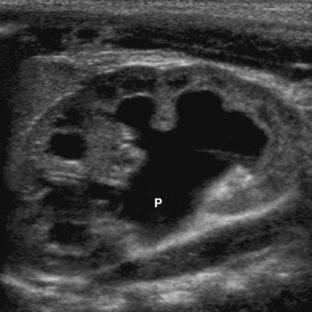

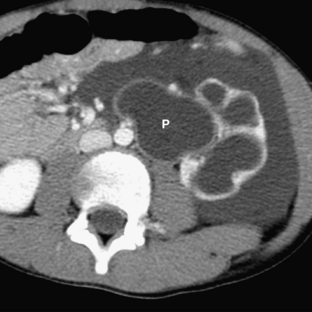

Multicystic Dysplastic Kidney

Multicystic dysplastic kidney (MCDK) is thought to be related to severe obstruction of the renal collecting system during fetal development. The site of the obstruction determines the imaging appearance. The most common appearance of MCDK is that of a grapelike collection of variably sized cysts that do not appear to communicate (Fig. 6-13). The absence of a central dominant cyst differentiates MCDK from severe hydronephrosis. However, if the level of the fetal obstruction is within the proximal ureter, the “hydronephrotic” form of MCDK can occur; in this there is a central pelvis surrounded by dilatated cysts. In such cases, renal scintigraphy can be useful in differentiating severe UPJ obstruction from MCDK. In MCDK, no trace or accumulation is seen within the renal pelvis on 4-hour images. In patients with MCDK, it is important to exclude other associated congenital anomalies of the contralateral kidney. UPJ obstruction is commonly identified. Rarely, MCDK can be isolated to an upper or lower pole.

Ureteropelvic Duplications

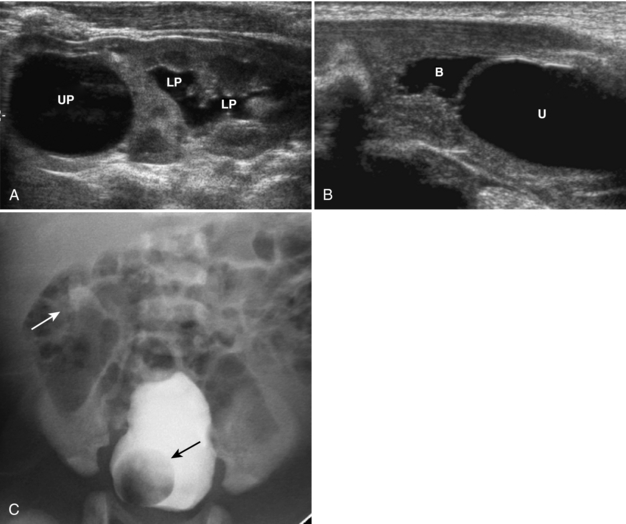

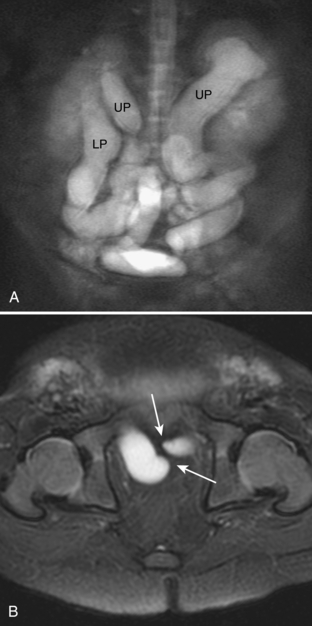

The term ureteropelvic duplication refers to a broad range of anatomic variations ranging in severity from incomplete to complete. The incomplete form of duplication is more common than the complete form. With incomplete duplication, there can be a bifid renal pelvis, two ureters superiorly that join in midureter, or duplicated ureters that join just prior to insertion into the bladder wall. With complete duplication there are two completely separate ureters that have separate orifices into the bladder. Ureteropelvic duplication is thought to occur secondary to premature division or duplication of the ureteral bud. Such duplications are five times more common unilaterally than bilaterally. On ultrasound, incomplete renal duplication may appear as an area of echogenicity similar to the renal cortex separating the echogenic central renal fat into superior and inferior components (Fig. 6-14). Noncomplicated, incomplete renal duplications have little significance and should be thought of as a normal variation. Children with incomplete duplication are not at increased risk for urinary tract disease as compared to children without duplications.

In patients with complete ureteropelvic duplication, there is a higher incidence of urinary tract infection, obstruction, vesicoureteral reflux, and parenchymal scarring. In these patients the ureteral orifice of the upper pole moiety inserts more medially and more inferiorly than the orifice of the lower pole ureter. This is known as the Weigert-Meyer rule. The lower pole system is more prone to vesicoureteral reflux and UPJ obstruction. The upper pole system is more prone to obstruction secondary to ureterocele (Figs. 6-15A-C, 6-16A, B).

URETEROCELE

A ureterocele is defined as dilatation of the distal ureter. The dilatated portion of the ureter lies between the mucosal and muscular layers of the bladder. The ureteral orifice is usually stenotic or obstructed. Ureteroceles are defined as simple when they are positioned at the expected orifice of the ureter at the lateral aspect of the trigone; they are defined as ectopic when they are associated with an ectopic insertion of the ureter. Ectopic ureteroceles can be quite large and are almost always associated with a duplicated collecting system (see Figs. 6-15, 6-16). The ureter from the upper pole moiety is associated with the ureterocele. There can be marked associated dilatation of that ureter and the upper pole moiety collecting system. On VCUGs, ureteroceles appear as round, well-defined filling defects, best visualized on early filling views (see Fig. 6-15). Ureteroceles may be compressed and not visualized when the bladder is distended by contrast. Sometimes the ureteroceles can invert and appear as diverticula. On ultrasound, typically a dilatated ureter is seen to terminate in a round, anechoic intravesicular cystic structure (see Fig. 6-15). Usually there is associated dilatation of the upper pole moiety.