LEARNING OBJECTIVES

1. Define tracheomegaly.

2. Name five common causes of tracheobronchomegaly.

3. Name five causes of focal or diffuse tracheal narrowing.

4. Name four types of bronchiectasis and identify each type on chest computed tomography (CT).

5. Name five common causes of bronchiectasis.

6. Recognize the typical appearance of cystic fibrosis (CF) on chest radiography and CT.

7. Name five important things to look for on a chest radiograph when the patient history is “asthma.”

8. Name three types of pulmonary emphysema and identify each type on chest CT.

9. Recognize the findings of α-1-antitrypsin deficiency on a chest radiograph and CT.

10. Recognize the findings of Kartagener syndrome on a chest radiograph and CT and name the three major components of the syndrome.

11. Define the term giant bulla, differentiate giant bulla from pulmonary emphysema, and state the role of imaging in patient selection for bullectomy.

12. Recognize and describe the significance of a pattern of mosaic lung attenuation on chest CT.

Airway disorders can be categorized into those that involve the trachea, those that involve the bronchi, and those that involve the bronchioles, the smallest branching airways leading to alveoli. Many disorders can, and frequently do, involve more than one airway compartment. Tracheal disorders will be discussed first, and disorders involving both the bronchi and bronchioles will be discussed together. The reader is referred to Chapter 1 for a discussion of normal anatomy of the airways.

TRACHEAL DISORDERS

Tracheal shape varies, depending on the phase of the respiratory cycle. The intrathoracic trachea is round or elliptic on inspiration images and flat or horseshoe-shaped during and at the end of a forced exhalation as a result of anterior bowing of the posterior noncartilaginous tracheal membrane during exhalation (1). Upper limits of normal for coronal and sagittal tracheal dimensions, respectively, as determined by chest radiographs, are 25 and 27 mm for men and 21 and 23 mm for women. The lower limit of normal for both dimensions is 13 mm in men and 10 mm in women (2). Mean measurements on computed tomography (CT) of anteroposterior (AP) and transverse diameters of the extrathoracic trachea, respectively, are 20.1 and 18.4 mm (3); these can increase by as much as 15% in men with aging (4).

CT is superior to chest radiography for detection of abnormalities of the trachea and main bronchi; sensitivities in detecting disease on chest radiographs and CT are 66% and 97%, respectively (5). Spiral multidetector CT, which allows for the acquisition of a whole thoracic volume during a single breath-hold, eliminating respiratory motion, is the technique of choice for noninvasive imaging of the airways. Volume acquisition with multidetector CT has fostered a renewed interest in two-dimensional and three-dimensional (3D) reconstructions applied to the tracheobronchial tree. Potential clinical applications of 3D reconstructions, such as shaded surface display and volume rendering, include assisting with diagnoses, replacing bronchoscopy in some instances, and helping in surgical planning and endobronchial treatments (6). In the case of a lesion that completely obstructs an airway, CT allows visualization of the airway beyond the obstruction. However, CT’s virtual bronchoscopy is currently unable to show mucosal detail, and 3D postprocessing methods are time-consuming to perform and rarely performed in routine clinical practice.

Patients with tracheal disease can be asymptomatic or may present with cough, dyspnea, wheezing, or stridor. Because of the variety of conditions that can cause wheezing, a misdiagnosis of asthma is common (7). Tracheal disorders are generally organized into those that cause tracheal widening and those that cause narrowing. CT can demonstrate the degree of widening or narrowing, in addition to the location and extent of tracheal abnormality; it can also demonstrate the presence of associated extraluminal disease, postobstructive atelectasis, and pneumonia. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a valuable method for observing the trachea because of its multiplanar demonstration of the airway, the mediastinal vessels, and the other structures simultaneously, without the need for contrast medium or exposing the patient to radiation. MRI is particularly useful in children and in patients with either vascular rings or tracheal compression by the innominate artery.

Disorders That Cause Tracheal Widening

Congenital or nonacquired diffuse tracheal widening is much less common than tracheal narrowing and has a more limited differential diagnosis. The Mounier–Kuhn syndrome, which affects primarily men in the fourth and fifth decades, accounts for almost all cases of nonacquired tracheal widening (8). Thought to be congenital (9), it is an abnormality of the trachea and main bronchi characterized by atrophy or absence of elastic fibers and thinning of muscle, which allows the trachea and main bronchi to become flaccid and markedly dilated on inspiration, with narrowing or excessive collapse on expiration and cough. The abnormal airway dynamics and pooling of secretions in broad outpouchings, or diverticula, of redundant musculomembranous tissue between the cartilaginous rings predispose patients to the development of chronic pulmonary suppuration, bronchiectasis, emphysema, and pulmonary fibrosis (10). The trachea is involved from the subglottic region to the carina. A tracheal diameter greater than 3 cm is required for diagnosis, and tracheal widths up to 5.5 cm have been recorded (8). The radiographic and CT features of the condition include marked dilatation of the trachea and mainstem bronchi, tracheal diverticulosis, and a variable incidence of bronchiectasis and chronic pulmonary parenchymal disease (11,12).

Several conditions can result in acquired tracheobronchomegaly that may closely resemble that seen in Mounier–Kuhn syndrome (Table 13.1). Some degree of tracheal dilatation may be seen with aging (4,13) and in musicians who play wind instruments (13). Chronic infection, cigarette smoking, chronic bronchitis, emphysema, cystic fibrosis (CF), inhalation of noxious fumes, chronic intubation, and diffuse pulmonary fibrosis can also result in tracheobronchomegaly (10,14,15). Other conditions associated with tracheal widening, which may in fact be related to Mounier–Kuhn syndrome, are Ehlers–Danlos syndrome and cutis laxa (16,17). Although tracheal narrowing is the usual end result in relapsing polychondritis—a disorder of cartilaginous inflammation involving the nose, ear, trachea, and joints—diffuse tracheal widening may develop occasionally (18). In contrast, nasal and ear cartilage abnormalities are absent in Mounier–Kuhn syndrome. Additional causes of secondary tracheobronchomegaly are listed in Table 13.1. Nevertheless, the majority of cases appear to be sporadic, predominantly occurring in men in the third and fourth decades of life (9).

Table 13.1 DISORDERS THAT CAUSE TRACHEOBRONCHOMEGALY

Nonacquired

Mounier–Kuhn syndrome

Acquired

Common

Normal aging

Chronic airway infection

Cigarette smoking

Chronic bronchitis

Emphysema

Cystic fibrosis

Diffuse pulmonary fibrosis

Uncommon

Playing wind instruments

Inhalation of noxious fumes

Chronic intubation

Ehlers–Danlos syndrome

Cutis laxa

Marfan syndrome

Ataxia-telangiectasia

Ankylosing spondylitis

Kenny–Caffey syndrome

Brachmann–de Lange syndrome

Connective tissue diseases

Bruton-type agammaglobulinemia

Light-chain deposition disease

Disorders That Cause Tracheal Narrowing

Tracheal narrowing is seen with a variety of disorders and can be idiopathic (7, 19–21) (Table 13.2). Strictures of the trachea are usually caused by damage from a cuffed endotracheal or tracheostomy tube or trauma to the neck (22). Postintubation tracheal injuries remain the most common indication for tracheal resection and reconstruction, despite identification of the causes of these lesions and development of techniques for their avoidance (23). Tracheomalacia, which is diagnosed when the trachea collapses more than 50% on expiration, can also be caused by trauma, and it may be recognized only on dynamic or expiratory CT scanning (1,24).

Saber-sheath trachea is diffuse intrathoracic narrowing of the trachea, with the coronal diameter reaching two-thirds (or less) of the sagittal diameter when measured 1.0 cm above the top of the aortic arch (25). More than 95% of patients with this deformity have clinical evidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and saber-sheath trachea is considered an insensitive but specific sign for COPD on standard chest radiography (25,26).

Relapsing polychondritis is a systemic autoimmune connective tissue disease in which cartilage is affected diffusely by recurrent episodes of inflammation. The pinnal, nasal, laryngeal, and tracheal cartilages are most commonly involved. The major airways are involved in more than 50% of cases, and recurrent pneumonia is the most common cause of death in these patients (8,27). CT shows diffuse or multifocal fixed narrowing of the tracheobronchial lumen, with associated thickening of the wall (28,29). Dense calcium deposits may be seen in the thickened tracheal cartilage (30).

Table 13.2 DISORDERS THAT CAUSE TRACHEAL NARROWING

Extrinsic

Masses (e.g., thyroid, aberrant vessels, enlarged nodes)

Fibrosing mediastinitis

Intrinsic

Congenital tracheal narrowing

Infection

Granulomatous disorders (e.g., granulomatosis with polyangiitis [Wegener granulomatosis], sarcoidosis)

Neoplasms

Trauma, including intubation

Amyloidosis

Relapsing polychondritis

Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica

Saber-sheath trachea

Idiopathic

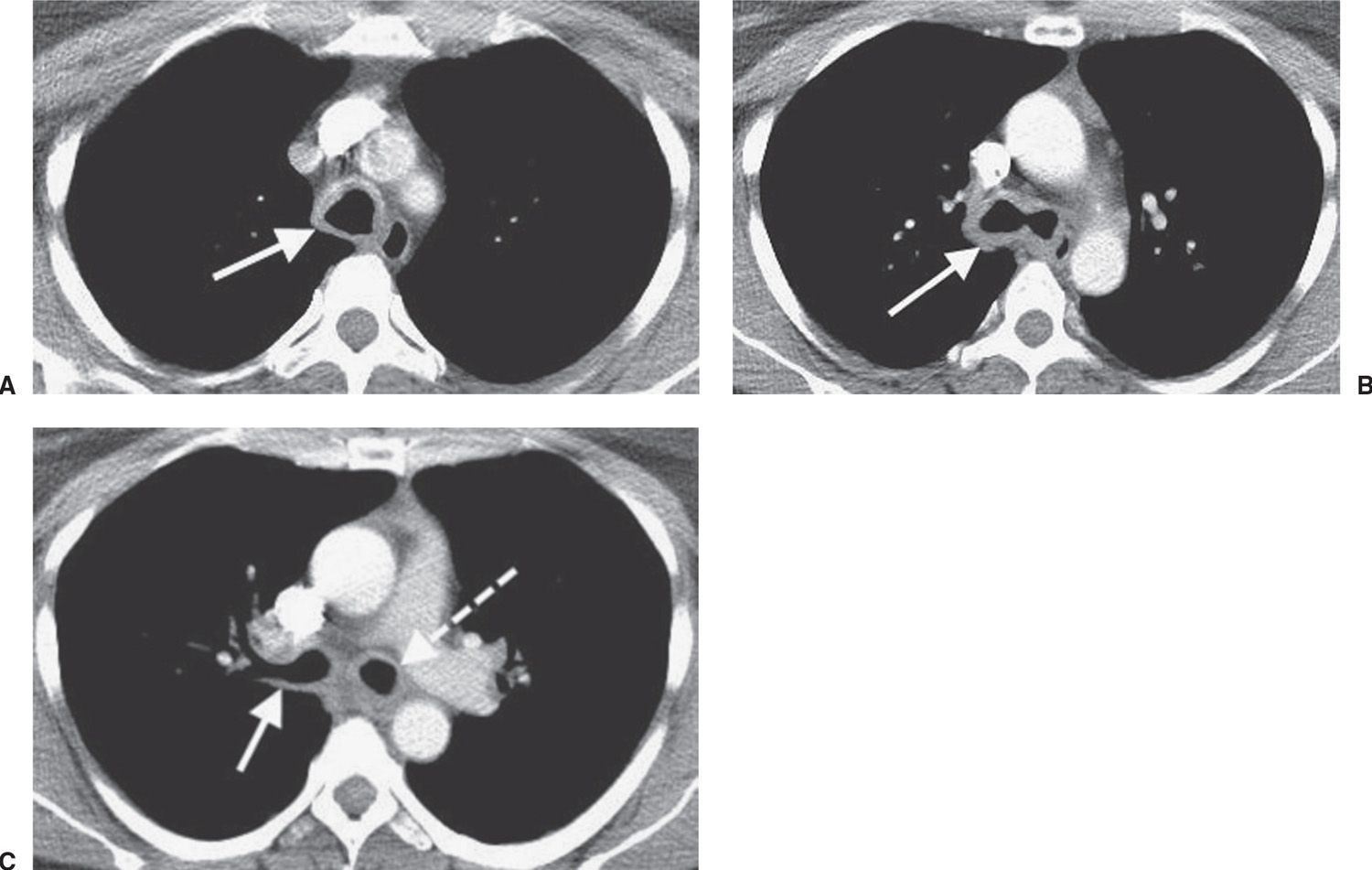

Amyloidosis of the respiratory tract, both primary and secondary, is a rare condition that produces focal or diffuse irregular narrowing of the airway by submucosal deposits of amyloid (22). Both radiography and CT of the chest can demonstrate diffuse narrowing or show nodular protrusions into the tracheal lumen that can be calcified (Fig. 13.1) (8).

Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica is a rare, benign condition characterized by multiple submucosal osteocartilaginous growths along the inner anterolateral surfaces of the trachea (31,32). Although the etiology is unknown, theories have linked this disorder to chronic inflammation, degenerative processes, amyloidosis, and neoplasia (33–35). Radiography and CT of the chest show multiple sessile nodular tumors, with or without calcification, extending over a long segment of the trachea and into the main bronchi. In contrast, the nodules in amyloidosis may be circumferential and can be distinguished from those of tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica, in which there is always sparing of the posterior membranous wall.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener granulomatosis) is characterized by granulomatous vasculitis of the upper and lower respiratory tract, usually in conjunction with renal and other organ involvement. The CT appearance of airway involvement includes circumferential narrowing of the airway lumen, abnormal soft tissue within the tracheal rings, and dense irregular calcification of the tracheal cartilages (36).

Sarcoidosis is another granulomatous disorder that may rarely involve the trachea and bronchi. Granulomatous sarcoid lesions may exist intrinsically in the airway, or enlarged hilar nodes may compress the bronchi extrinsically (37,38).

Many viral, bacterial, or fungal diseases can involve the trachea. In North America, most cases of laryngotracheobronchitis are viral in nature; subglottic or laryngeal narrowing is common, but radiographically demonstrable tracheal narrowing is unusual (7).

Tracheobronchial Filling Defects

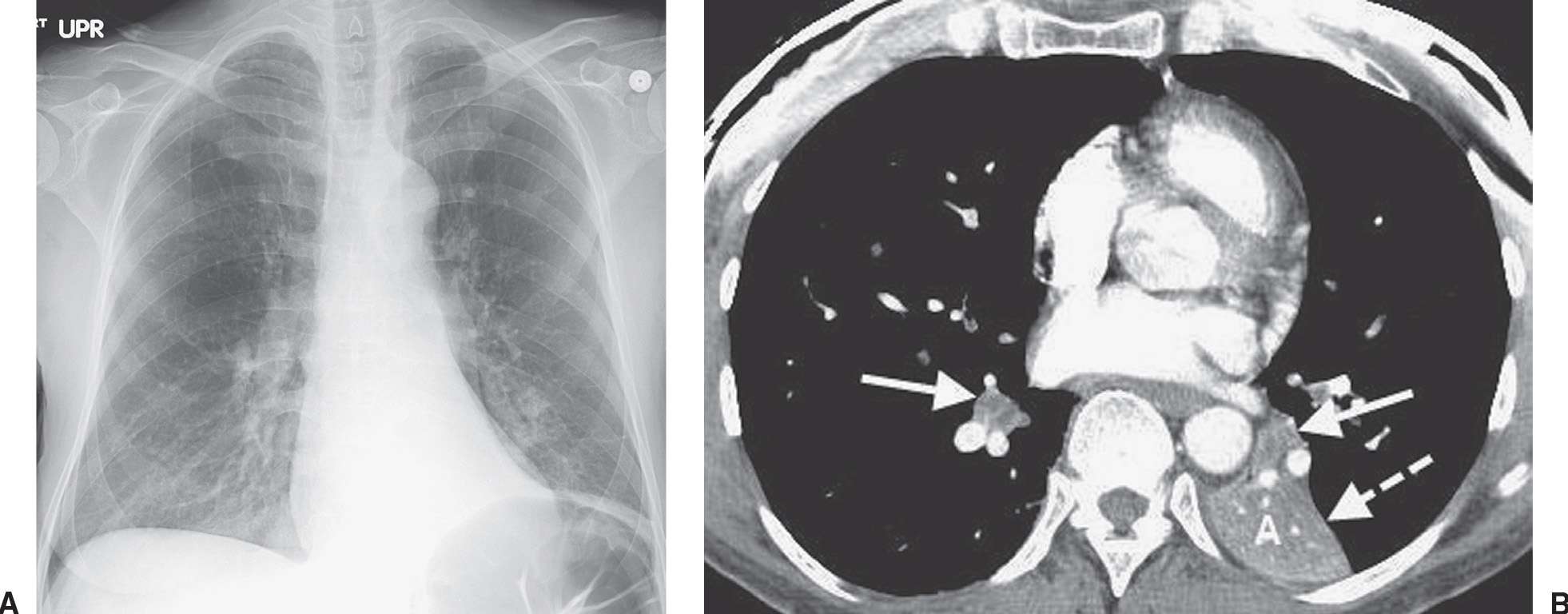

In adults, tracheobronchial filling defects are usually produced by mucus (Fig. 13.2) or neoplasms. Less common causes include papilloma, infections (Fig. 13.3), foreign bodies, broncholiths, and other miscellaneous disorders (Figs. 13.4 to 13.6). If mucus is suspected on a CT scan, it can be helpful to selectively repeat the scan at the region of interest after the patient has coughed.

Ninety percent of all adult primary tracheal tumors are malignant (39). Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common tracheal and bronchial tumor (Fig. 13.7). The most common imaging appearance is a small sessile or polypoid lesion in the lower third of the trachea or an occluding mass within a main bronchus (Figs. 13.8 and 13.9). Adenoid cystic carcinoma is the second most common tracheal tumor. Nearly half of patients are younger than 30 years. On CT, it appears as a smooth, focal mass in the trachea or main bronchi (Figs. 13.10 and 13.11). The longitudinal extent is typically greater than the cross-sectional area. The most common airway tumor in adolescents and young adults is endobronchial carcinoid tumor. On CT it appears as a well-defined spherical or oval central bronchial mass with a slightly lobulated border and marked contrast enhancement (Fig. 13.12). Respiratory papillomatosis results from infection of the upper respiratory tract by the human papilloma virus and rarely occurs in adults (40). It predominately affects the larynx but may spread into the trachea, bronchi, and even lung (Fig. 13.13). The most common primary tumors that spread hematogenously to the large airways are adenocarcinomas (e.g., breast, colon kidney, lung) and melanoma (41) (Figs. 13.14 and 13.15).

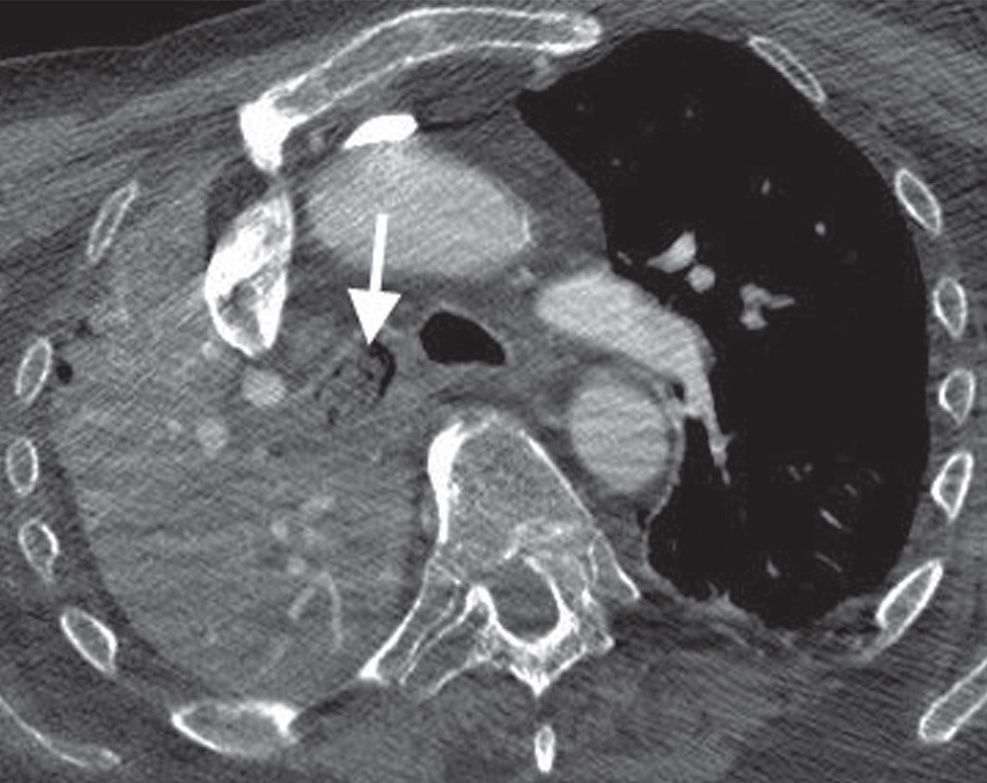

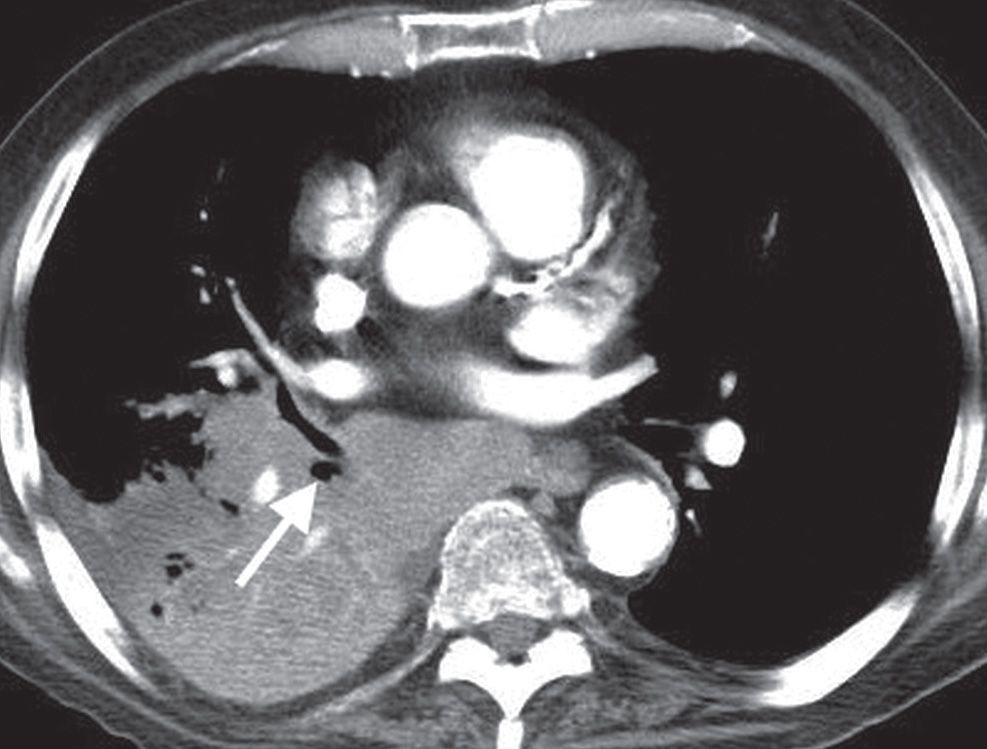

FIG. 13.1 • Tracheobronchial amyloidosis. A: CT of a 44-year-old woman with dysphagia and dyspnea on exertion shows circumferential thickening and calcification of the tracheal wall (arrow). B: CT at a level inferior to (A) shows thickening of the walls of the main bronchi (arrow). C: CT at a level inferior to (B) shows thickening of the wall of the right upper lobe bronchus (solid arrow) and left main bronchus (dashed arrow).

FIG. 13.2 • Mucous plugging. A: PA chest radiograph of a 45-year-old woman with shortness of breath after cervical spine fusion shows abnormal opacities in both lower lobes and volume loss in the left lower lobe. B: CT shows low-attenuation material in both lower lobe segmental bronchi (solid arrows), postobstructive atelectasis of the left lower lobe (A), and posteromedial displacement of the left major fissure (dashed arrow).

FIG. 13.3 • Endobronchial blood clot. CT of a 10-year-old girl with leukemia and Rhizopus necrotizing pneumonia shows a filling defect occluding the bronchus intermedius (arrow). The right middle and lower lobes were surgically resected; pathology showed pulmonary artery and vein thromboses, diffuse pneumonia and pulmonary hemorrhage, and clotted blood in the bronchus intermedius.

FIG. 13.4 • Endobronchial debris. CT shows debris filling the right mainstem bronchus (arrow) and postobstructive pneumonia of the right lung.

Foreign-body aspiration is more common in children than adults (42). In adults, the foreign body is usually aspirated food (Figs. 13.16 and 13.17). Aspiration of teeth or restorative dental material can be related to trauma, iatrogenic, or otherwise (Fig. 13.18).

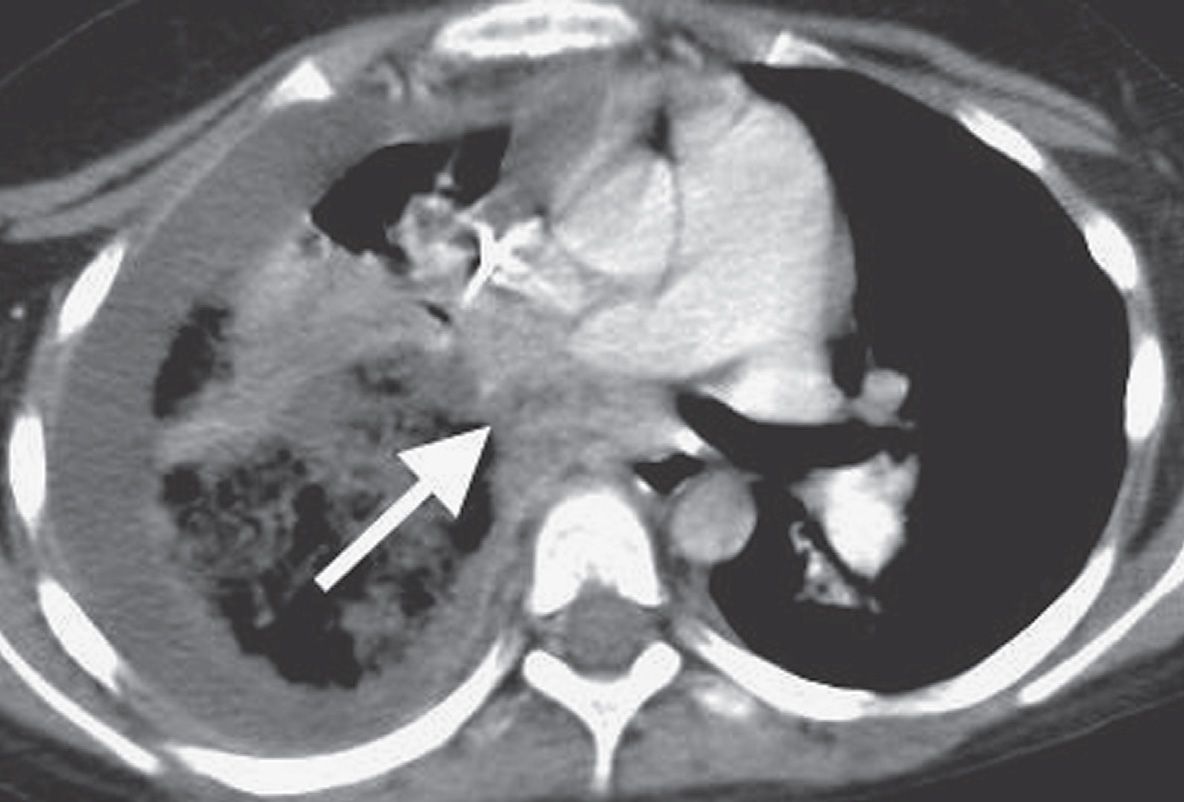

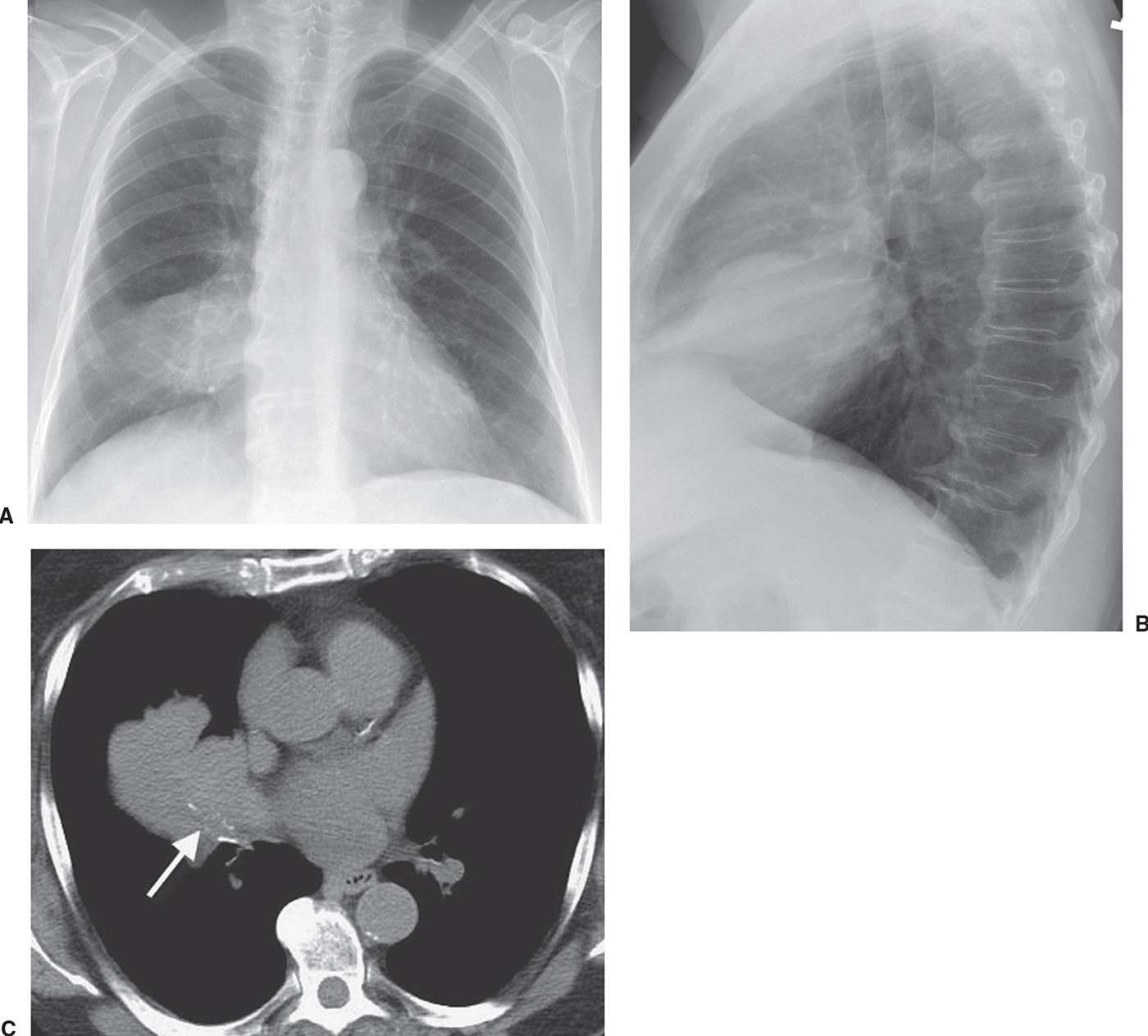

Broncholithiasis is characterized by compression on or erosion into an airway by calcified peribronchial lymph nodes (Figs. 13.19 and 13.20). Patients may occasionally present with expectorations of stones (lithoptysis). On CT, the broncholith is almost always accompanied by other calcified peribronchial, hilar, or mediastinal lymph nodes.

Tracheoesophageal Fistulas

Tracheoesophageal fistulas in adults are almost exclusively acquired lesions. They occur as a complication of intrathoracic malignancies (accounting for 60% of cases), infection, and trauma (43,44). The diagnosis is usually made with a fluoroscopic contrast study but can be made, in some cases, with CT. In addition to demonstrating the site of a fistula, CT can suggest the etiology and detect pulmonary and mediastinal complications (45).

FIG. 13.5 • Endobronchial blood clot. A: CT of an 18-year-old woman with hemoptysis shows a circumscribed mass in the left upper lobe bronchus (arrow). B: CT at a level superior to (A) shows consolidation and ground-glass opacity in the left upper lobe. Bronchoscopy confirmed a blood clot in the bronchus and hemorrhage in the lung.

FIG. 13.6 • Endobronchial lipoma. CT of a 65-year-old man with recurrent right middle lobe pneumonia shows a small circumscribed mass in the right middle lobe bronchus (arrow). The diagnosis was confirmed bronchoscopically.

FIG. 13.7 • Endobronchial squamous cell carcinoma. CT of a 63-year-old woman with cough shows a soft tissue mass that almost completely obliterates the lumen of the bronchus intermedius (arrow).

FIG. 13.8 • Endobronchial squamous cell carcinoma. CT of a 73-year-old man with cough shows a mass obstructing the right lower lobe bronchus (arrow) and postobstructive pneumonia in the right lower lobe.

FIG. 13.9 • Endobronchial squamous cell carcinoma. CT of a 52-year-old man with chest pain and 20-lb weight loss shows cutoff of the right middle lobe bronchus (arrow) and a surrounding mass in the right middle lobe.

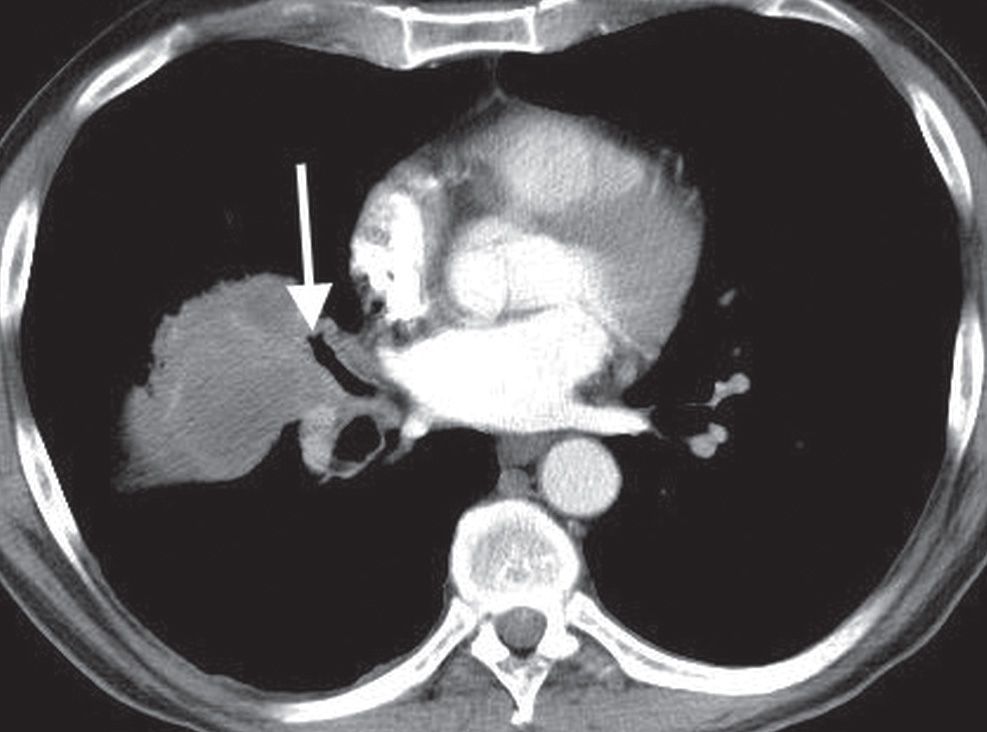

FIG. 13.10 • Tracheal adenoid cystic carcinoma. A: PA chest radiograph of a 59-year-old man with recurrent right middle lobe pneumonia and cough shows a linear band of opacity in the right midlung (arrow). B: Lateral view shows an oblique band of opacity paralleling the inferior aspect of the major fissure (arrow). C: Coronal reformatted CT shows a lobular soft tissue mass (arrow) almost completely obstructing the lumen of the trachea just above the level of the carina. D: Axial CT shows that the mass (arrow) almost completely fills the lumen of the trachea. E: CT at the level of the inferior pulmonary veins shows postobstructive atelectasis and pneumonia in the right middle lobe.

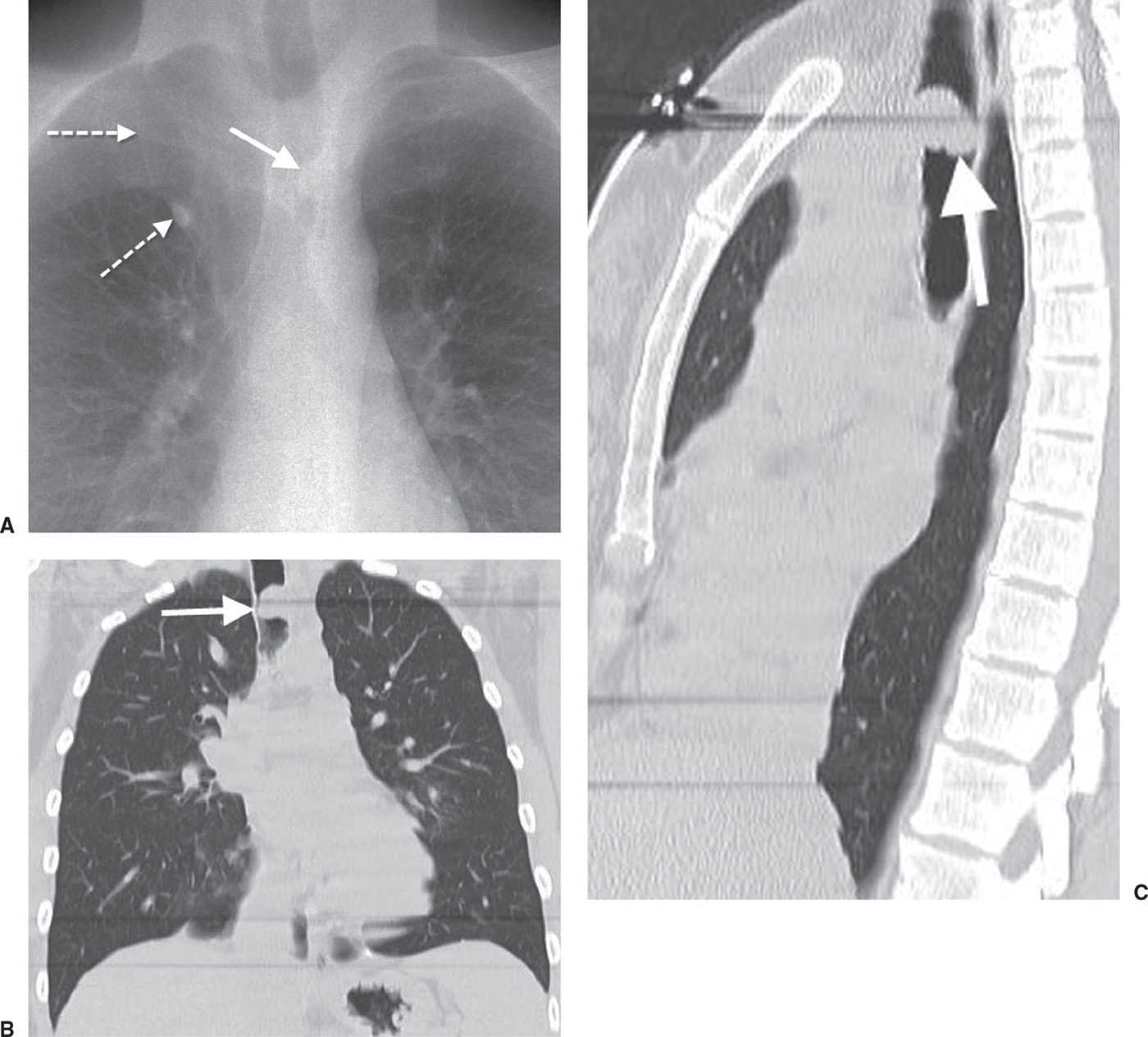

FIG. 13.11 • Tracheal adenoid cystic carcinoma. A: Coned-view dual-image chest radiograph of a 31-year-old woman with shortness of breath, wheezing, and hemoptysis shows a mass overlying the trachea (solid arrow). Note an incidental accessory azygos fissure (dashed arrows). Coronal (B) and sagittal (C) reformatted CT images confirm the endotracheal mass (arrows). The patient was treated for asthma for a year prior to the diagnosis of adenoid cystic carcinoma.

FIG. 13.12 • Endobronchial carcinoid. CT shows a circumscribed mass in the left upper lobe bronchus (arrow).

FIG. 13.13 • Tracheal papillomatosis. CT of a 28-year-old man with cough shows a polypoid mass in the trachea (arrow).

FIG. 13.14 • Tracheal metastasis. A: PA chest radiograph of a 75-year-old woman with endometrial carcinoma shows a mass adjacent to the right hilum. B: Lateral view shows the mass projected over the heart. The contours of the mass suggest that it is related to the inferior edge of the major fissure. C: Axial CT shows low-attenuation material obliterating the lumen of the right middle lobe bronchus (arrow). Note that the bronchial wall is outlined by calcium. Tumor is growing through the bronchus into the right middle lobe. The opacity seen on the chest radiograph represents tumor and collapsed right middle lobe.

FIG. 13.15 • Tracheal metastasis. CT of a 64-year-old woman with renal cell carcinoma shows a soft tissue mass adjacent to the anterior wall of the trachea (arrow), representing one of many biopsy-proven metastases to the trachea. Mucus could have a similar appearance, but it will usually clear with a repeated scan after the patient clears the throat.

FIG. 13.16 • Endobronchial foreign body. CT shows a radiopaque foreign body (arrow) in the left main bronchus. Note the hyperlucency and hyperinflation of the left upper and lower lobes secondary to air trapping. A chicken bone was removed from the airway.

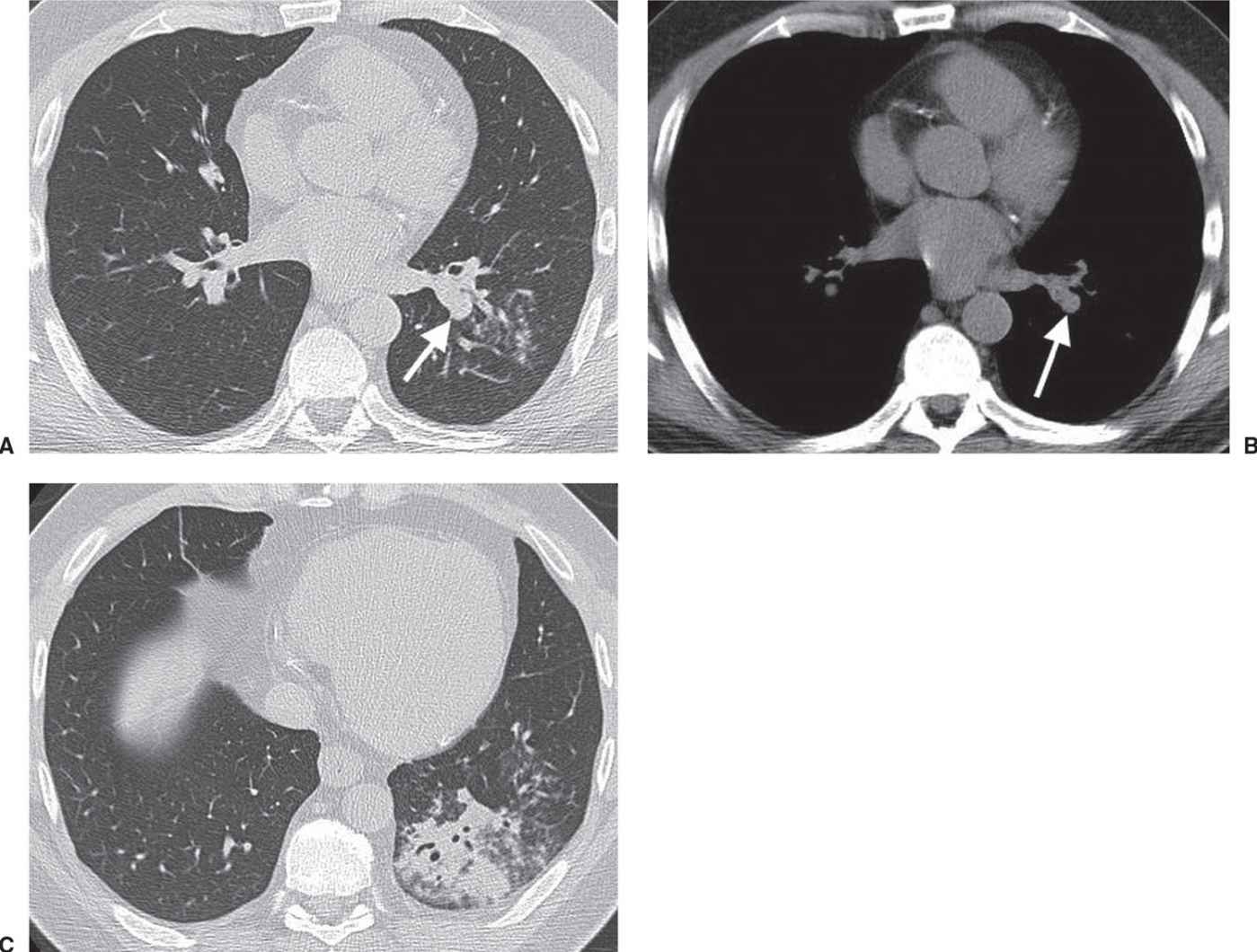

FIG. 13.17 • Endobronchial foreign body. CT with lung windowing (A) and soft tissue windowing (B) of a 42-year-old man with cough, dyspnea, wheezing, and fever show a round mass occluding a left lower lobe segmental bronchus (arrow). C: CT at a level inferior to (A) shows postobstructive pneumonia in the left lower lobe. An unpopped popcorn kernel was endoscopically removed from the bronchus.

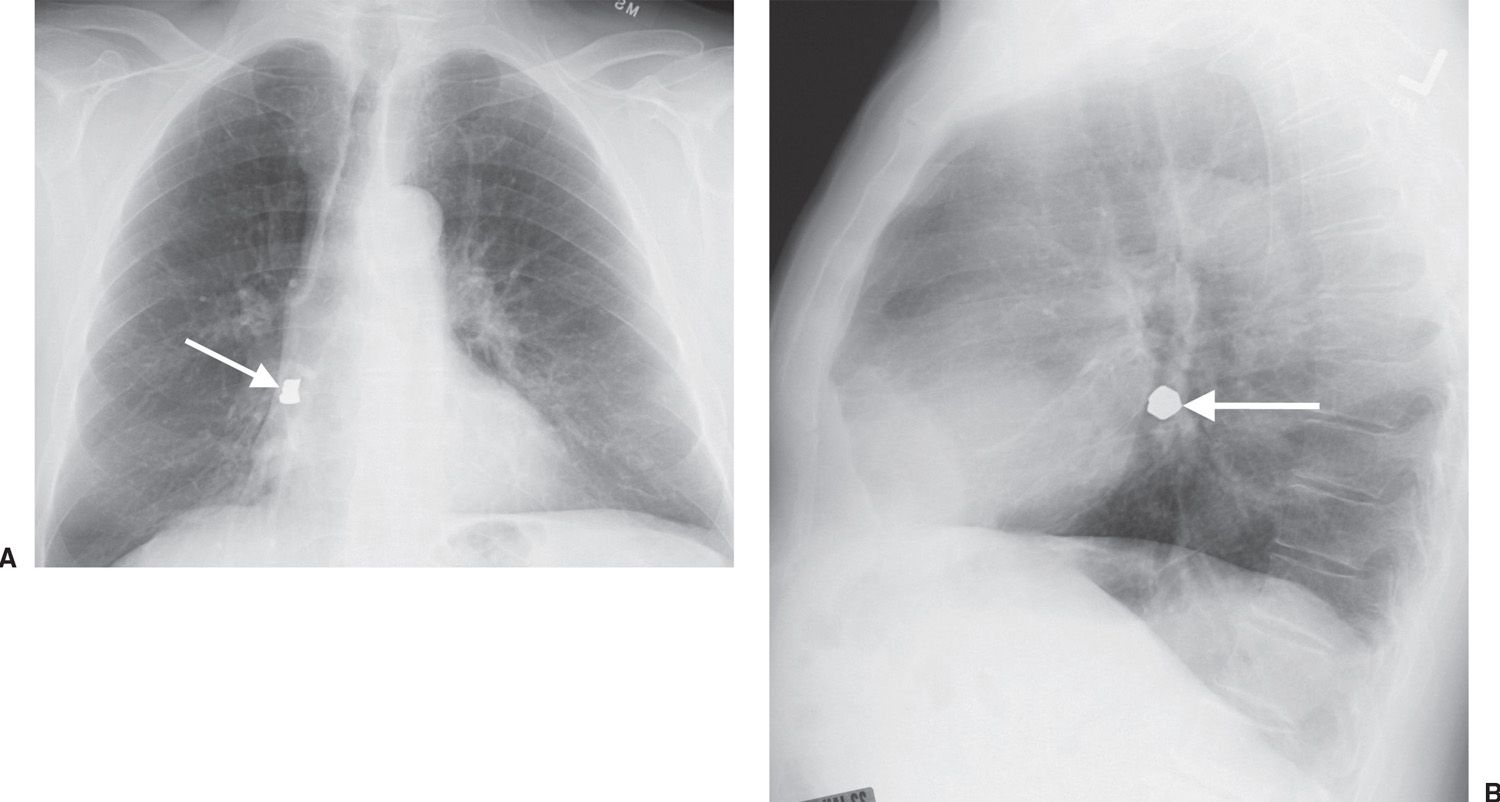

FIG. 13.18 • Aspirated tooth. PA (A) and lateral (B) chest radiographs show a radiopaque foreign body in the right lower lobe (arrow), representing a tooth that was dislodged during attempt at intubation.

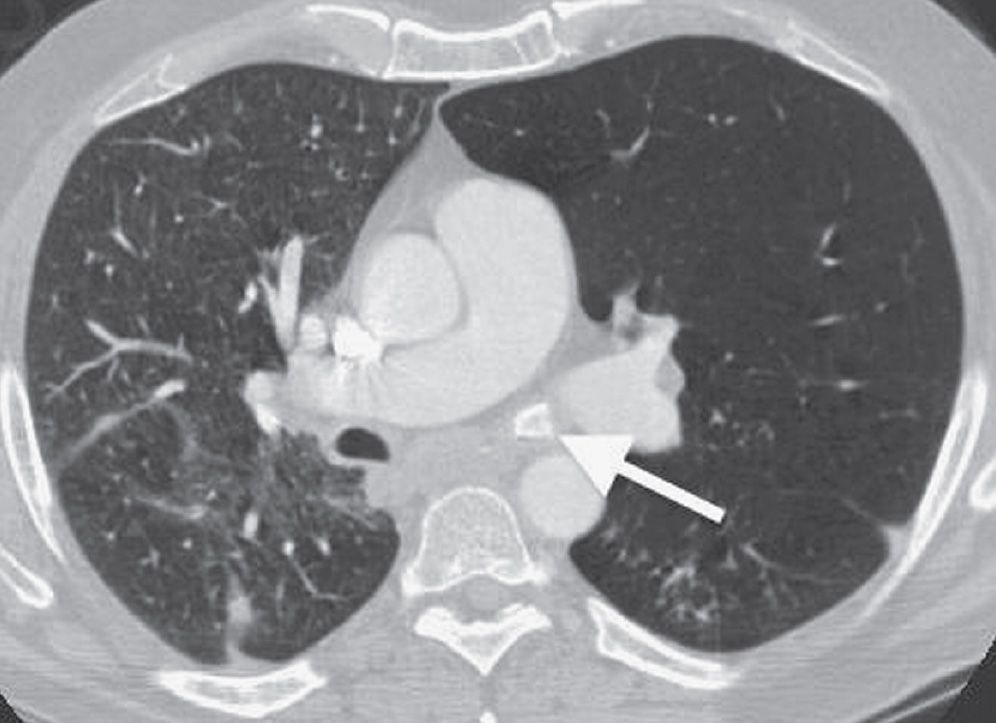

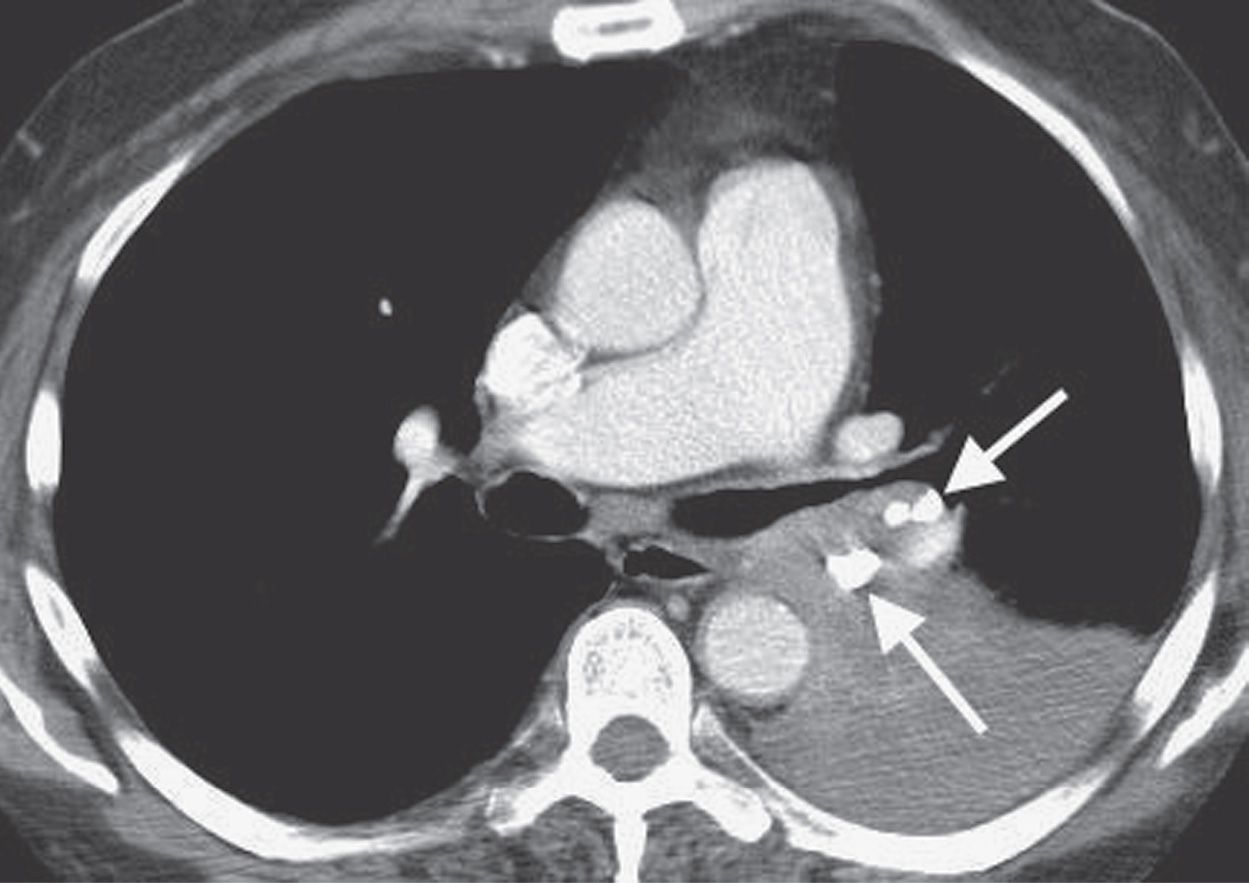

FIG. 13.19 • Broncholithiasis. CT of a 72-year-old man with cough, wheezing, and shortness of breath shows large calcifications in the left hilum and left lower lobe bronchus (arrows) and postobstructive atelectasis of the left lower lobe.

FIG. 13.20 • Broncholithiasis. A: PA chest radiograph of a 51-year-old man with cough shows abnormal opacification obscuring the right heart border. B: Lateral view shows the abnormal opacity projected over the heart, limited by the minor fissure superiorly and the lower aspect of the right major fissure inferiorly. C: CT shows a large calcification occluding the right middle lobe bronchus (arrow) and postobstructive atelectasis and pneumonia in the right middle lobe.

Congenital Tracheobronchial Anomalies

Congenital tracheobronchial anomalies can present as life-threatening emergencies at birth, or they may go undiagnosed for years. Clinical symptoms are often nonspecific, and radiographic evaluation is frequently required to localize and characterize the lesion before endoscopy, surgery, or medical management. The radiologist must be on the alert for unsuspected additional associated anomalies involving airways, lungs, great vessels, and the esophagus, which occur with relative frequency.

Tracheal webs produce localized areas of narrowing with no associated deformity of the underlying cartilage. The thickness of the webs determines the severity of obstruction and the therapeutic approach (46). Congenital tracheal stenosis may occur in any portion of the trachea, usually involving more length and depth of the trachea than webs, and is more likely to require resection rather than dilatation alone. Stenosis secondary to long-term compression by a dilated esophagus, abnormal great vessels, or cervicomediastinal masses results in a focal fibrous and cartilaginous deformity that persists for some time after the mass is removed. Congenital tracheal stenosis is frequently associated with bronchial stenosis; pulmonary hypoplasia or agenesis; tracheal bronchus; tracheoesophageal fistula; tracheomalacia; anomalies of vertebrae, ribs, and thumbs; and cardiac anomalies.

Tracheomalacia is an abnormally flaccid trachea that may involve all or part of the trachea and results in abnormal anteroposterior tracheal collapse during expiration of greater than or equal to 50% of cross-sectional area. The innominate artery compression syndrome can result in secondary tracheomalacia, in which there is persistent narrowing of the anterior tracheal wall at the level of the thoracic inlet. Short trachea, which occurs when there are 15 or fewer tracheal rings, can be diagnosed on CT when the tracheal bifurcation lies above the fourth thoracic vertebral body in children younger than 2 years or above the fifth thoracic vertebra thereafter (47).

A tracheal bronchus (so-called “pig bronchus,” or bronchus suis) is the most common anomalous airway pattern, reported in 2% of children during bronchoscopy examination (48). It occurs most commonly in boys, arising most often from the right lateral tracheal wall within 2 cm of the carina. A tracheal bronchus can be a true supernumerary bronchus or anatomical variant, with a normal but displaced upper lobe, segmental, or subsegmental bronchus. It can be asymptomatic, or it may result in right upper lobe infection, atelectasis, or bronchiectasis, usually from a stenotic bronchial segment and poorly cleared secretions. The CT appearance is that of a bronchus arising from the trachea in a section more cephalad than the carina (Fig. 13.21) (49).

CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASE

COPD refers to a group of disorders characterized by chronic or recurrent obstruction to airflow. Five principal disorders fall under this heading (Table 13.3), although the term is commonly used clinically to refer to pulmonary emphysema. Because these disorders are sometimes difficult to distinguish from one another on chest radiography, the term COPD should not be restricted to pulmonary emphysema.

Asthma

There is no universally accepted definition of asthma; it may be regarded as a diffuse, obstructive lung disease with hyperreactivity of the airways to a variety of stimuli and a high degree of reversibility of the obstructive process, which may occur either spontaneously or as a result of treatment. Asthma is a complex disorder involving biochemical, autonomic, immunologic, infectious, endocrine, and psychological factors in varying degrees in different individuals. Both large and small airways may be involved, again to varying degrees. The three elements that contribute to airway obstruction in asthma are (i) spasm of smooth muscle; (ii) edema and inflammation of the mucous membranes lining the airways; and (iii) intraluminal exudation of mucus, inflammatory cells, and cellular debris. Asthma can be a benign, self-limiting problem; it can lead to acute respiratory failure; or it can be a chronic, recurrent disease that leads to debilitating, irreversible airflow obstruction and COPD. Emphysema is not a prominent finding in the lungs of nonsmoking patients with asthma, even in those with severe disease (50).

FIG. 13.21 • Aberrant tracheal bronchus. CT of a 58-year-old woman with cough and recurrent pneumonia shows a so-called “pig bronchus” (arrow) arising from the right lateral wall of the trachea, above the level of the carina.

Table 13.3 CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASE

“ABCCE”

Asthma

Bronchiectasis

Chronic bronchitis/bronchiolitis

Cystic fibrosis

Emphysema

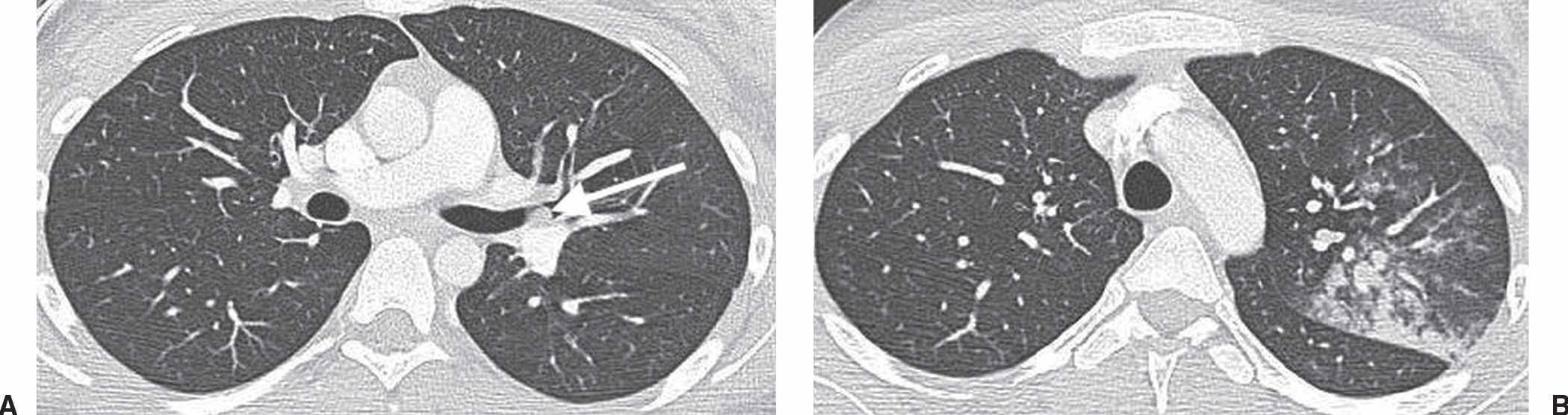

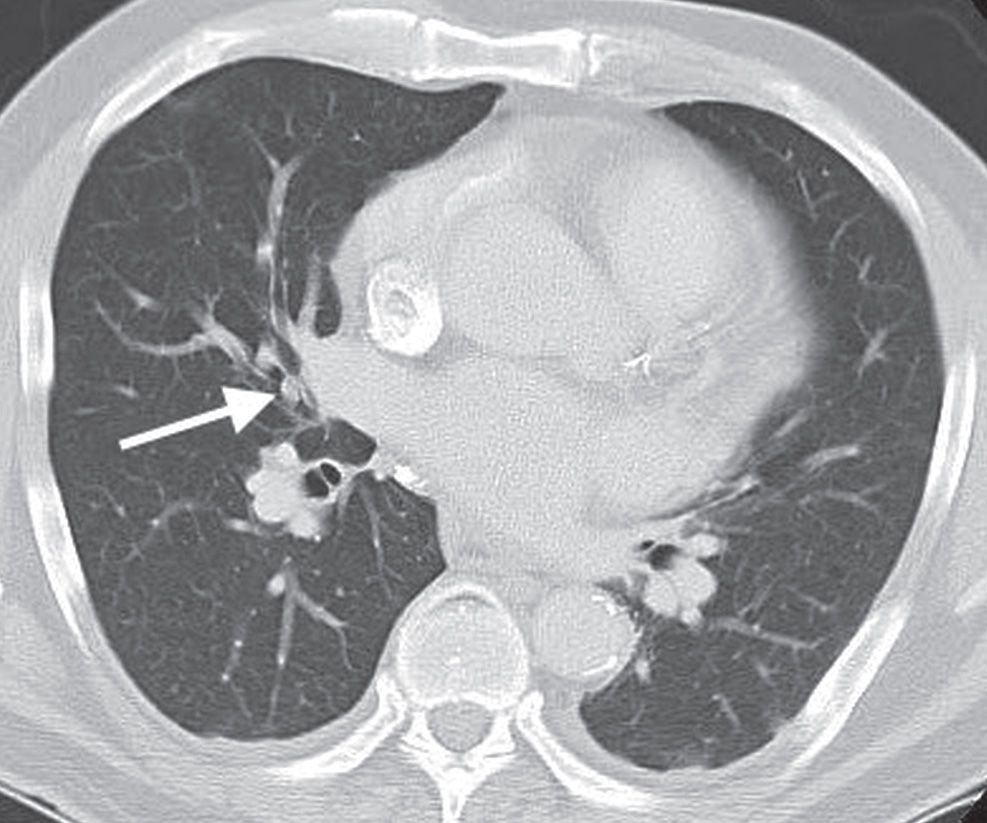

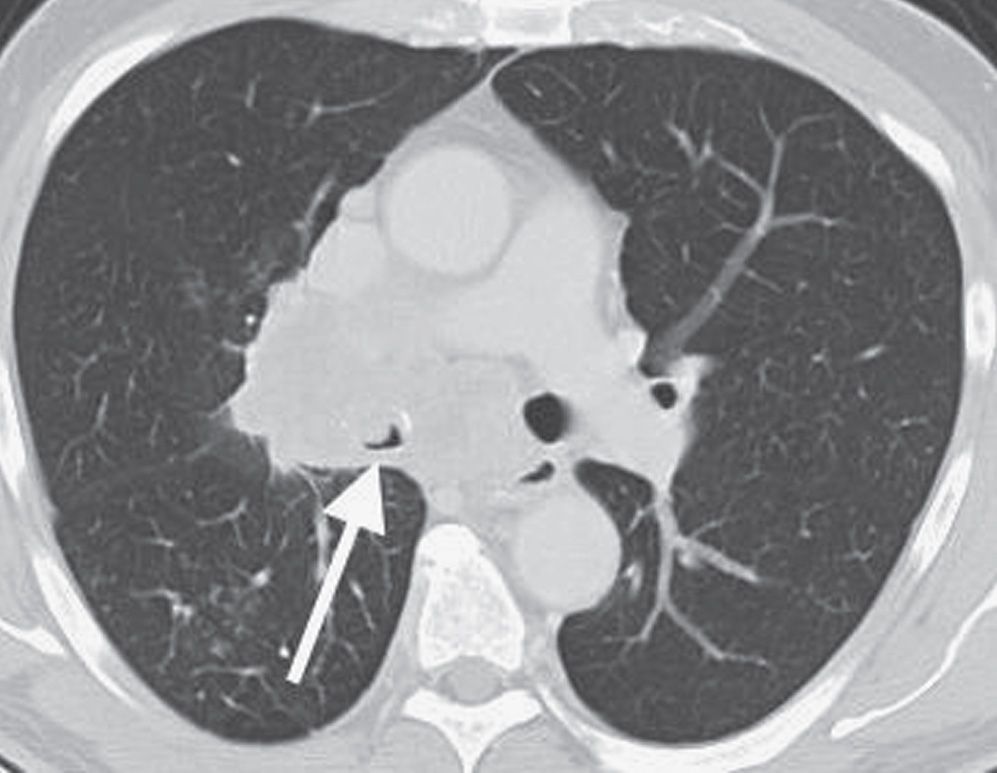

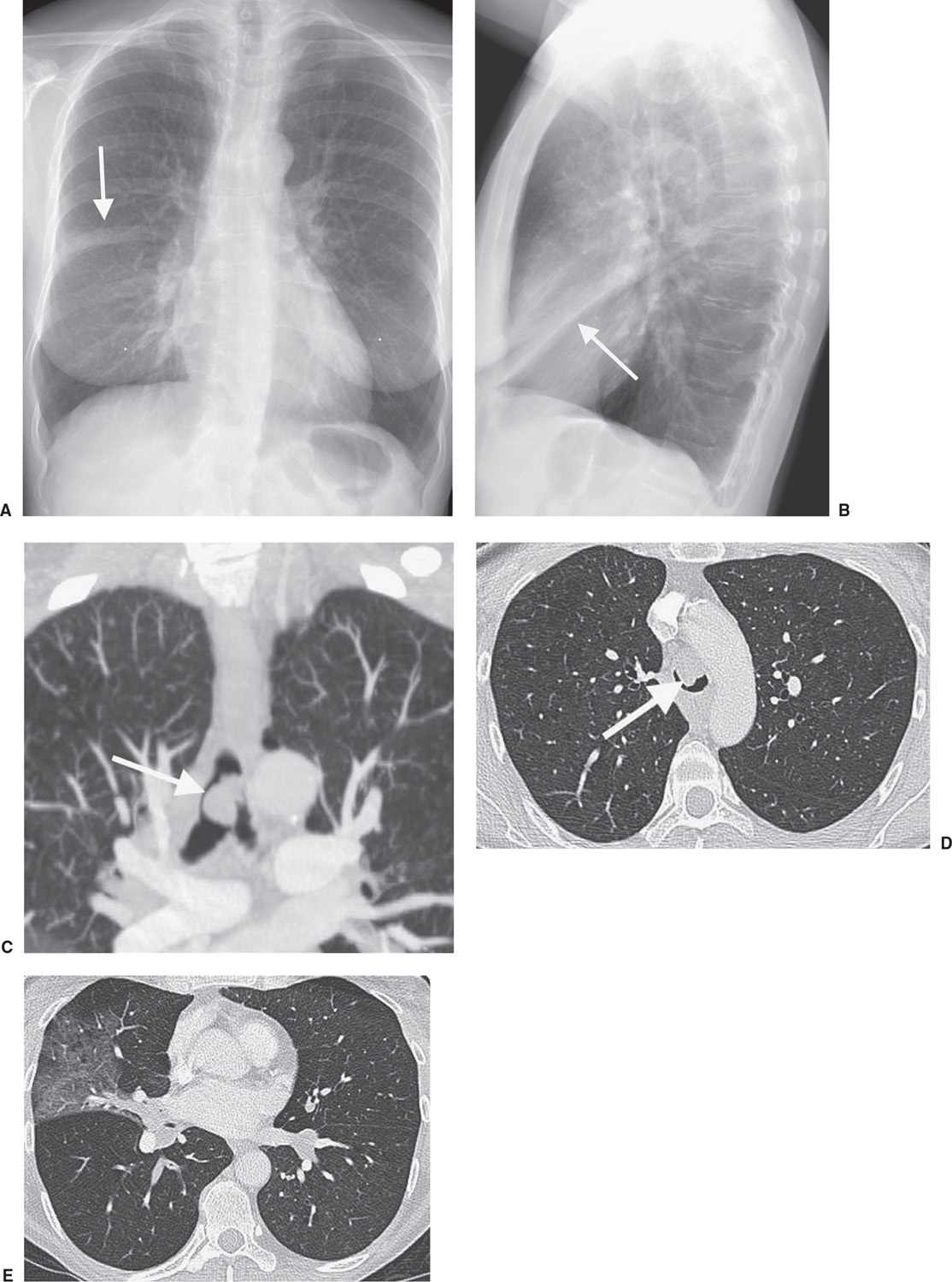

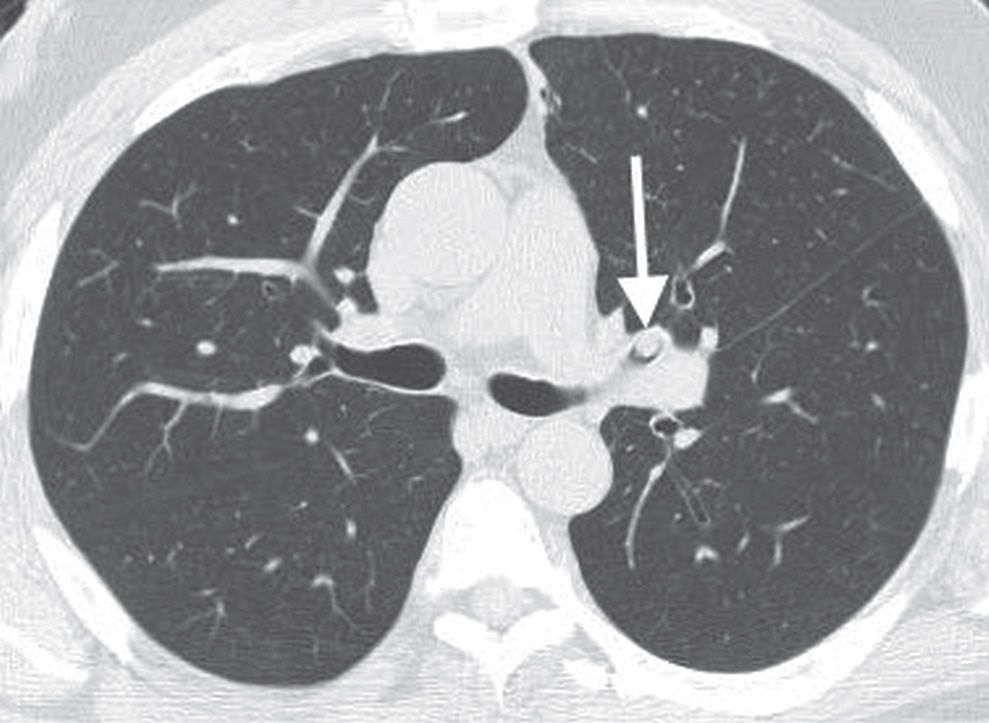

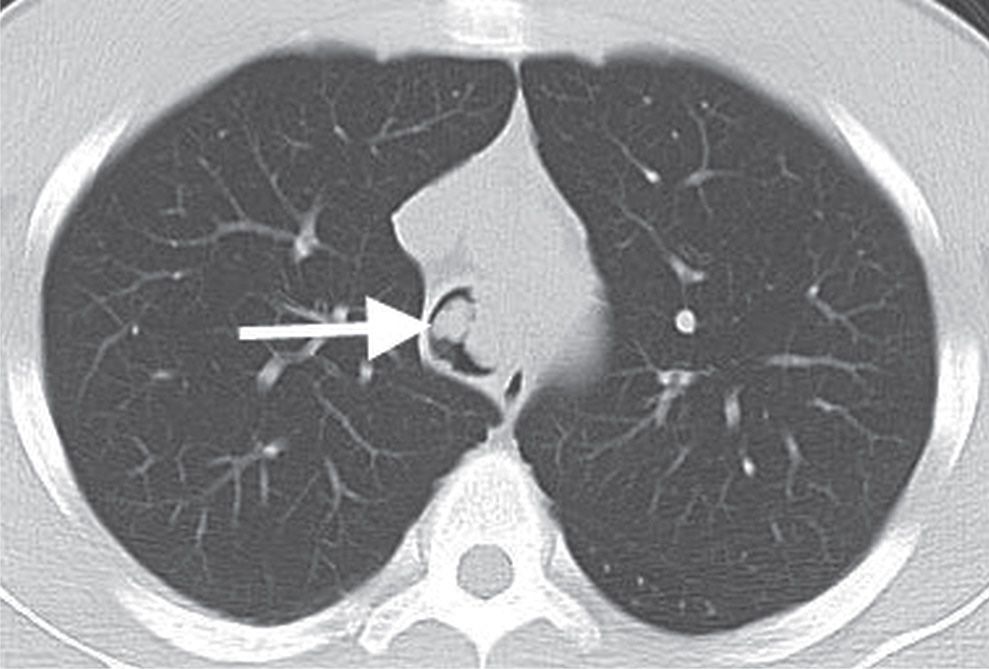

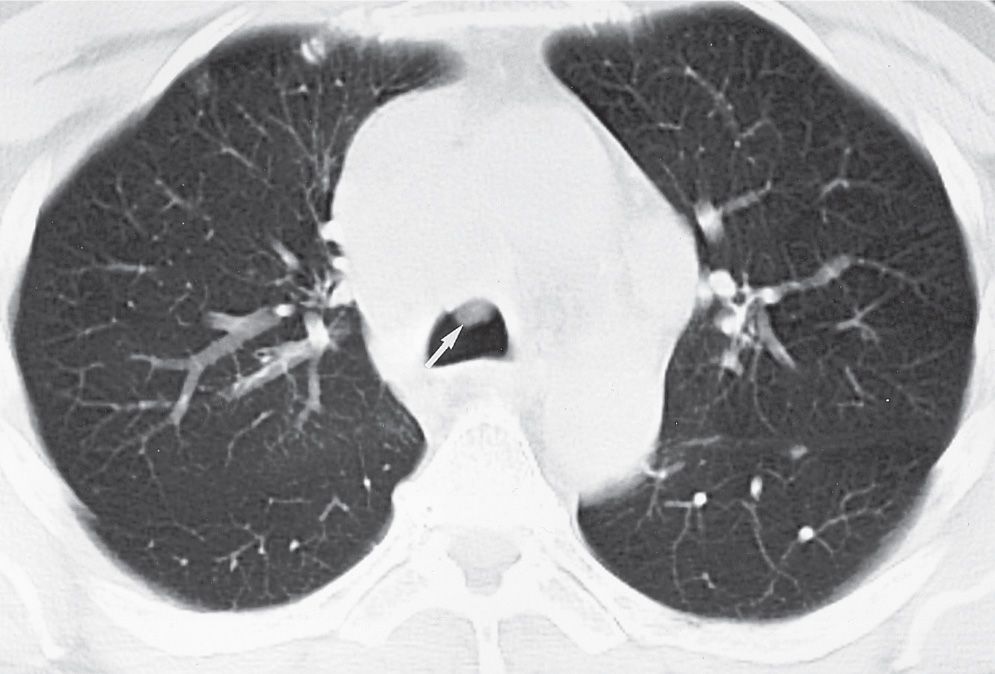

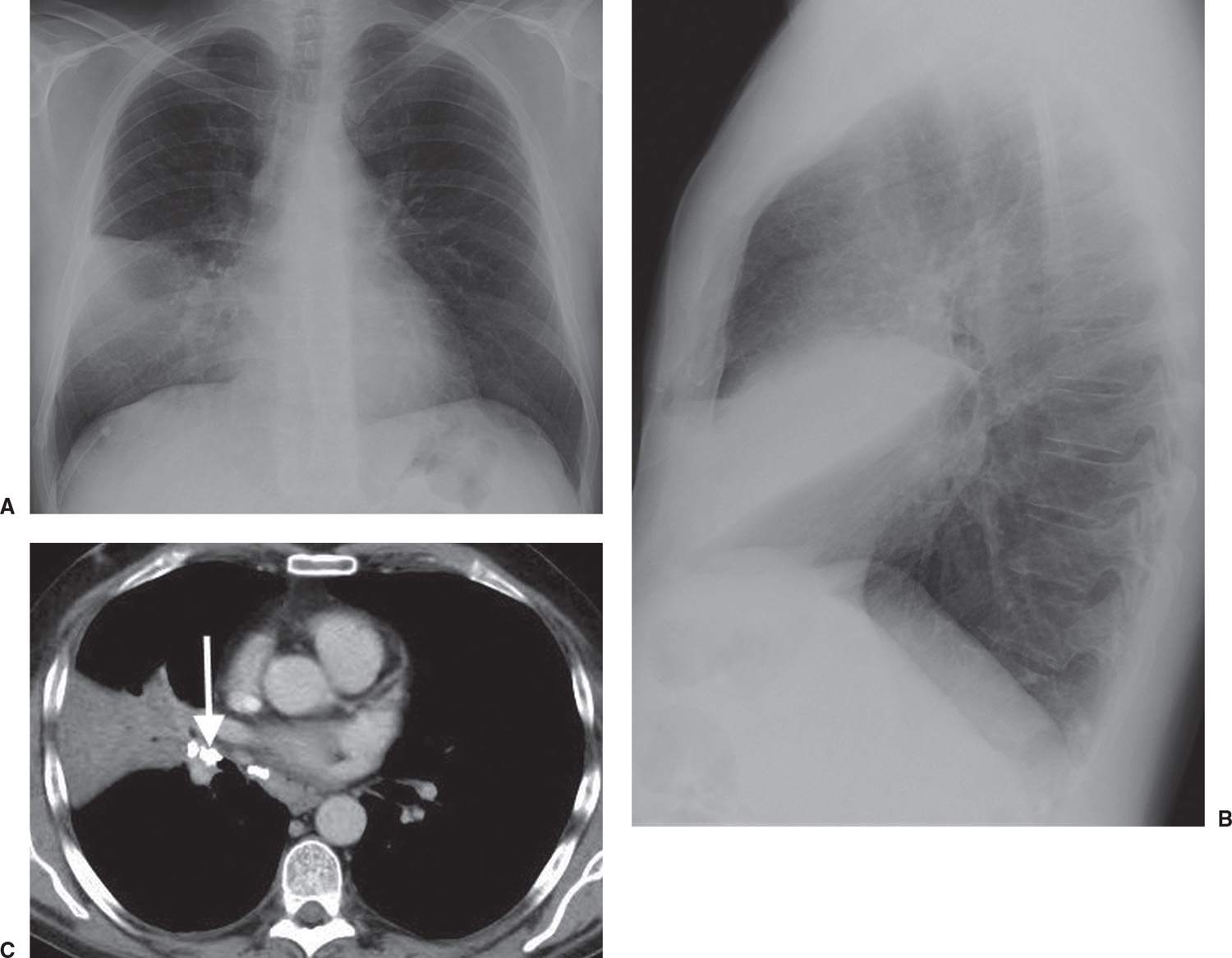

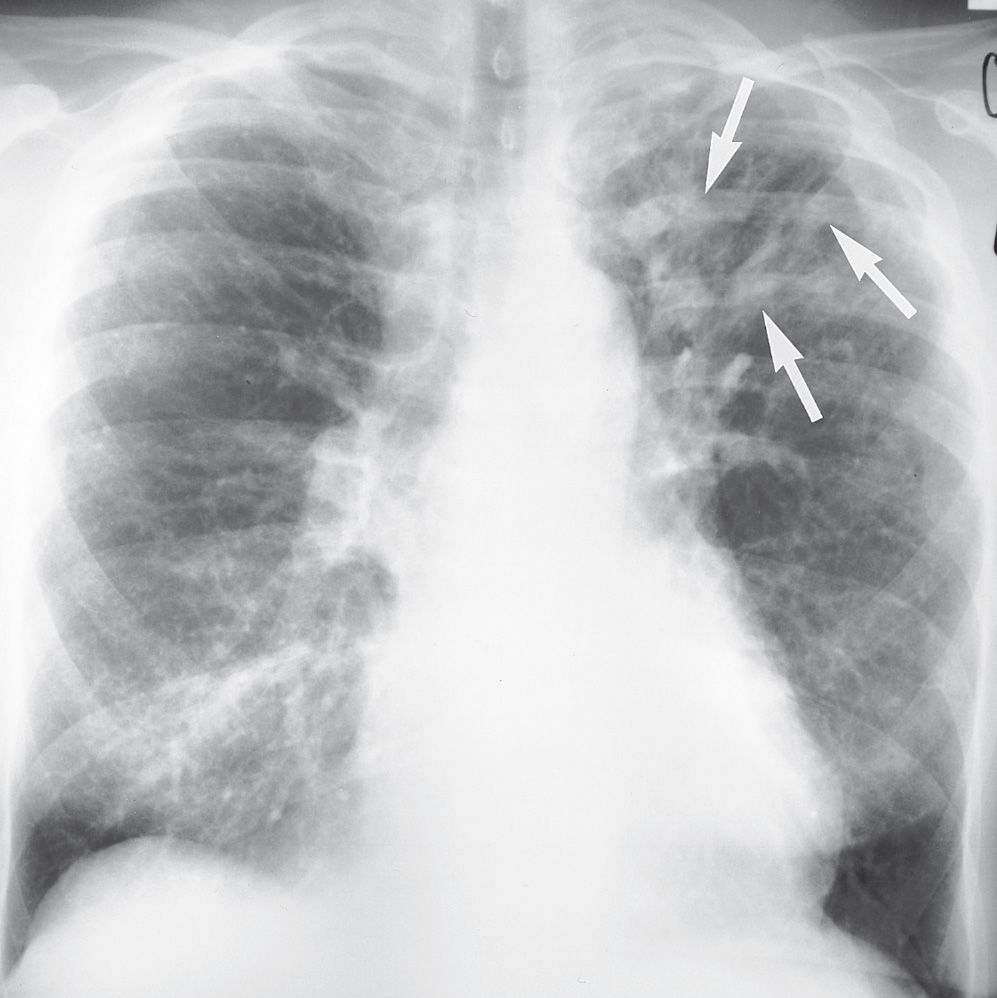

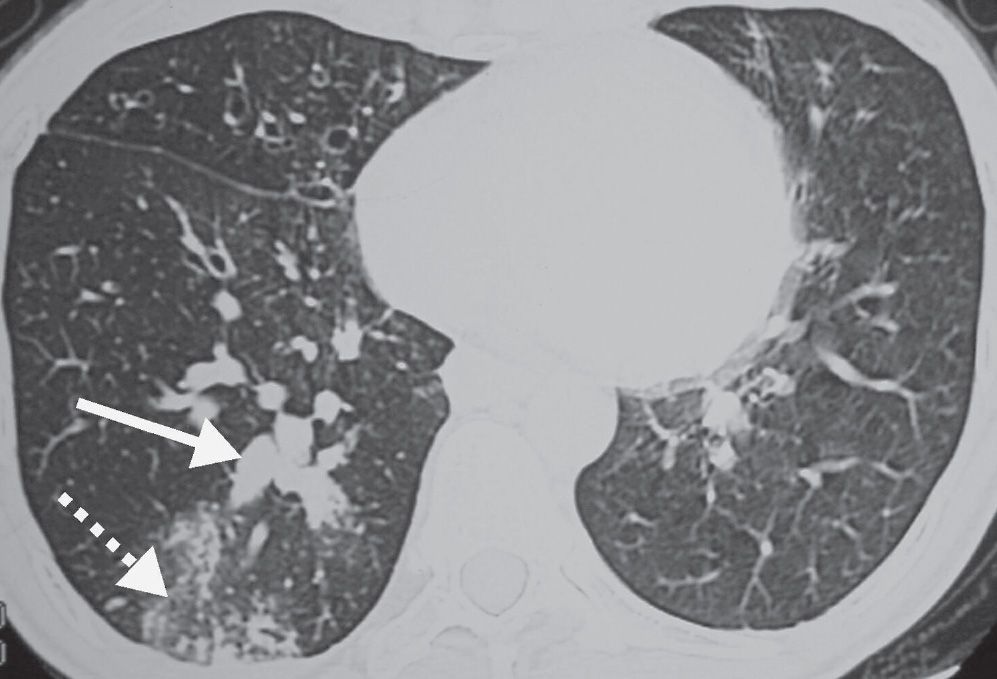

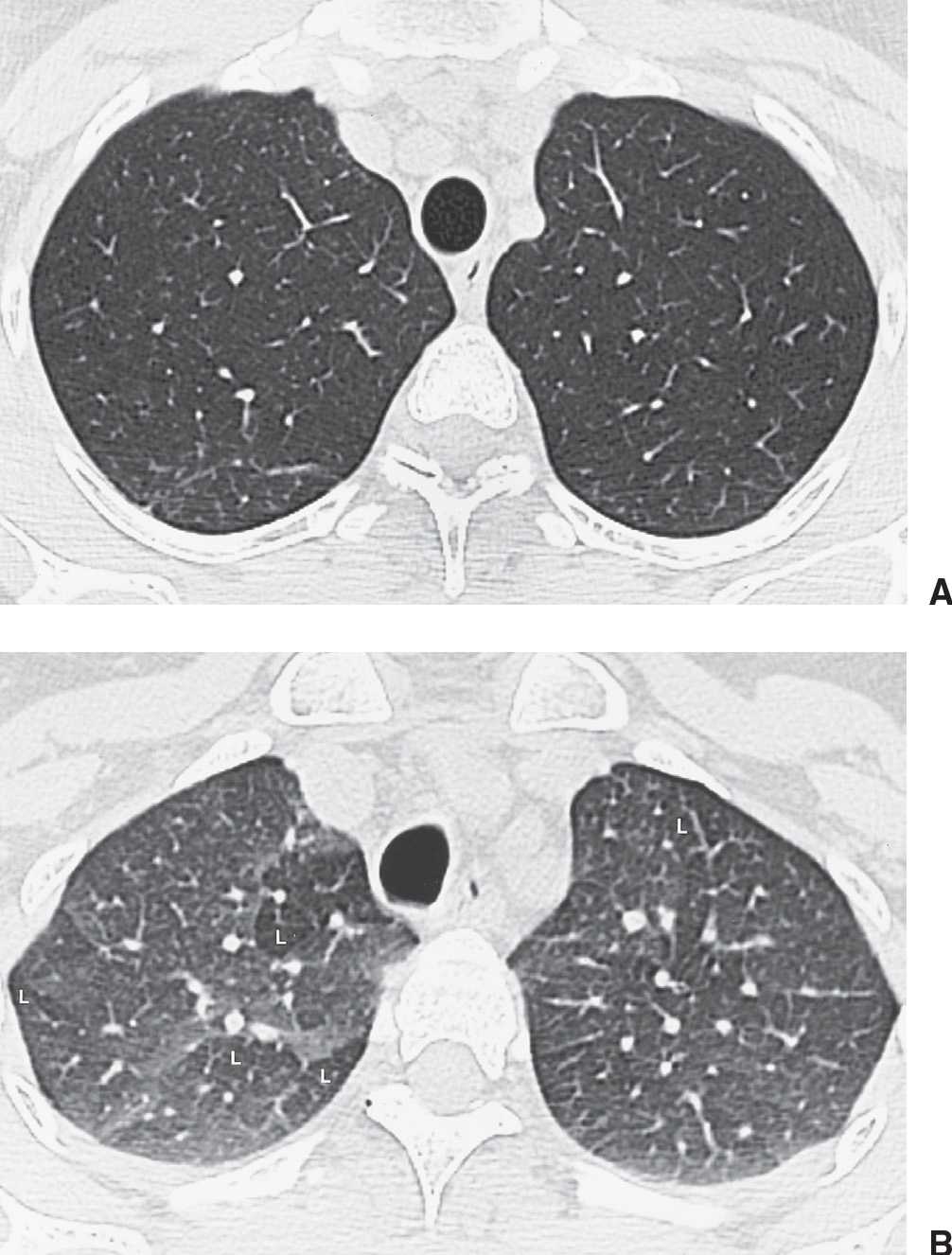

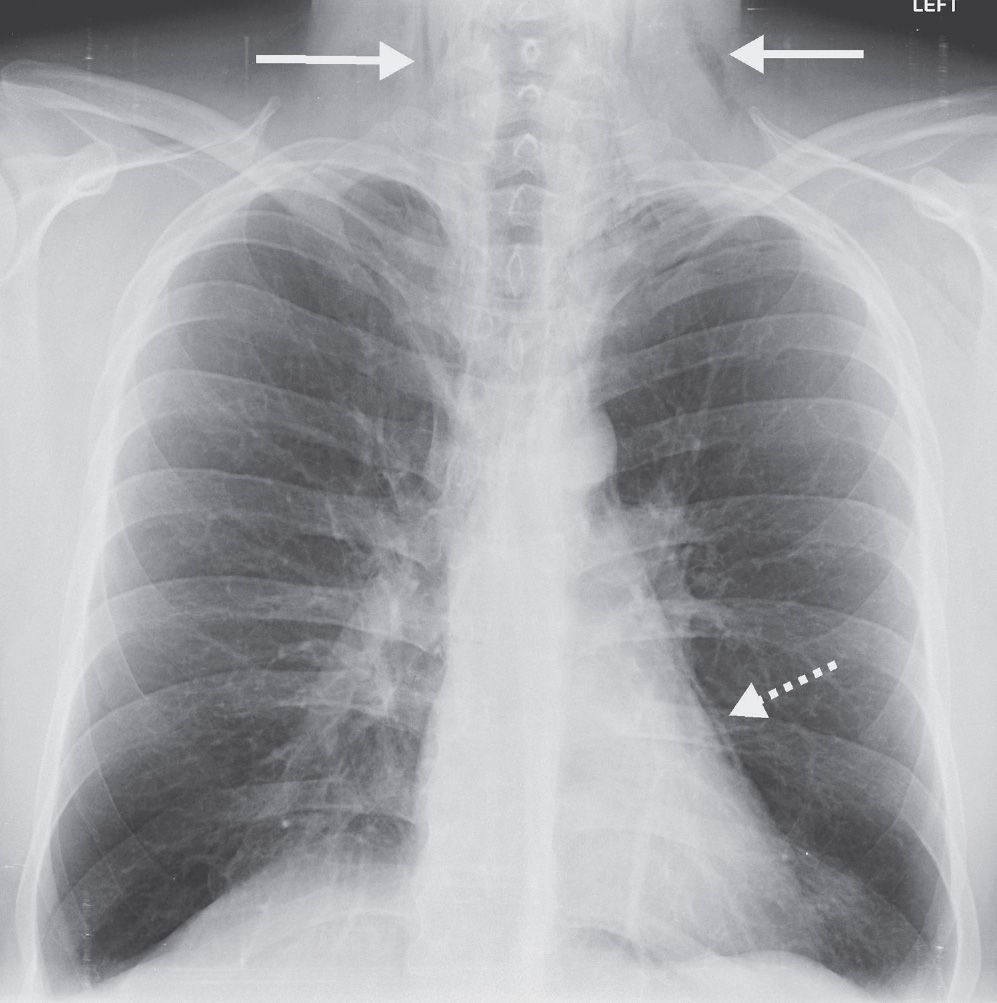

Chest radiographs of patients with asthma can be normal, show increased lung markings and hyperinflation, or show low lung volumes and multifocal atelectasis. CT findings may include bronchiectasis involving mostly subsegmental and distal bronchi, bronchial wall thickening, small centrilobular opacities, and decreased lung attenuation (51). Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) occurs with a greater prevalence in patients with asthma and CF (52) (Figs. 13.22 and 13.23). Central bronchiectasis on CT is the hallmark of ABPA. Bronchial wall thickening in asthma (which is assessed subjectively on CT) may reflect bronchial and peribronchial inflammation as well as increased smooth muscle, mucous gland, cartilage, and submucosal area (53,54). Areas of hyperlucency are caused by decreased lung perfusion secondary to reflex vasoconstriction in hypoventilated areas, and by air trapping (55) (Fig. 13.24). Emphysema seen on the CT scans of patients with asthma is attributed to cigarette smoking (56). Small centrilobular opacities may correspond to plugging or to thickening of the bronchiole walls (53). Because central airway lesions and mitral stenosis can produce symptoms attributed to asthma, the airways, cardiac silhouette, and pulmonary vasculature should always be evaluated closely on every chest radiograph when the clinical history is “asthma.” The chest radiograph should also be assessed for evidence of pneumonia, which is known to exacerbate asthma, and pneumomediastinum (Fig. 13.25) and pneumothorax, as evidence of alveolar rupture that can be caused by wheezing and coughing (Table 13.4).

FIG. 13.22 • Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. PA chest radiograph of a 64-year-old woman with a long history of asthma shows multiple tubular opacities in the left upper lobe (arrows), representing dilated bronchi filled with mucus, debris, and fungal hyphae.

FIG. 13.23 • Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. CT shows central bronchial dilatation and impaction (solid arrow). Peripheral nodular and ground-glass opacities (dashed arrow) represent impaction of small airways and peribronchiolar inflammation.

FIG. 13.24 • Asthma. A: Inspiratory CT of a 34-year-old woman with steroid-dependent asthma is normal. Note the round contour of the trachea. B: Expiratory image at the same level as (A) shows areas of lucency (L), representing air trapping. Note the flattened posterior tracheal contour on expiration.

FIG. 13.25 • Pneumomediastinum. PA chest radiograph of a patient with asthma shows mediastinal air outlining the heart (dashed arrow) and extending into the neck bilaterally (solid arrows).

Table 13.4 THINGS TO LOOK FOR ON THE CHEST RADIOGRAPH WHEN THE PATIENT HISTORY IS “ASTHMA”

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree