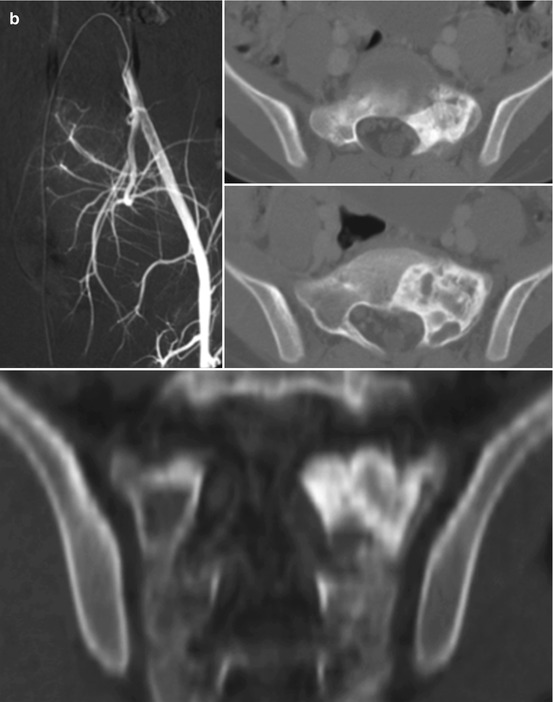

Fig. 11.1

Results after treatment of ABC of the sacrum with selective arterial embolization. (a) Digital subtraction angiography (left corner) shows the pathological tumor vascularization arising from branches of the internal iliac arteries; axial CT scan (right corner) of the pelvis shows an osteolytic lesion extending to the anterior and posterior sacral space; coronal CT scan (below) shows the involvement of proximal sacral vertebrae. (b) The same imaging studies after embolization show complete occlusion of tumor vascularization and healing of the lesion as evident by ossification and tumor size reduction. The patient is asymptomatic

11.5.3 Sclerosing Agents Injection

11.5.4 Bone Induction Agents Injection

Recently, the use of bone induction agents to treat ABC is debated. The rational of treatment is to interrupt the destructive osteoclastic process and promote spontaneous bone regeneration. Several materials have been used in clinical setting with conflicting results. Calcium sulfate injections do not appear to be effective [32], whereas demineralized bone matrix seems to be effective, possibly because it induces the bone morphogenic process [44].

Donati et al. reported a case of ABC of the sacrum treated unsuccessfully with arterial embolization. The patient was then treated with percutaneous injection of demineralized bone matrix together with bone marrow concentrate, with evidence of progressive bone production inside the cystic area at 6 and 12 years of follow-up [45]. However, more research on the effectiveness of this technique is needed.

11.5.5 Denosumab

Denosumab is a human monoclonal antibody that inhibits RANKL (receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand), reducing bone resorption. The drug has been approved for treatment of osteoporosis and bone metastasis and has been reported active and useful for medical treatment of giant cell tumor of bone. Recently, RANKL has been associated also with ABC growth, justifying use of denosumab as medical treatment [15, 46, 47]. Skubitz et al. reported a gradual pain resolution in a 27 years old male with sacral ABC treated with denosumab administration for 11 months [48]. They confirmed the absence of giant cell and presence of new bone formation at biopsy performed during follow-up. Ghermandi et al. reported good results in term of pain relief and complete ossification of the lesion in two cases unresponsive to selective arterial embolization treated with multiple administration of denosumab [49]. However, many questions remain regarding the use of denosumab in ABC and, awaiting further confirmations from ongoing studies, may be useful in cases not amenable to surgical interventions and unresponsive to selective arterial embolizations.

11.5.6 Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy as adjuvant treatment or alone has been suggested in the past as possible treatment for ABCs that are difficult to access by surgery, but currently it is not recommended to minimize the risk of postradiation sarcoma and severe complications including osteonecrosis, gonadal damage, and myelopathy [9, 13, 50–53]. Radiation should be reserved only for selected local recurrence cases.

11.6 Oncologic Outcome

Recurrence is reported in 10–44% of the cases [9, 10, 50]. Papagelopoulos et al. reported a recurrence rate of 14% on 35 primary ABCs of the pelvis surgically treated [3], and Capanna et al. reported a similar recurrence rate (13%) on 23 ABCs of the pelvis [54]. Recurrences are associated with incomplete excision [3, 9, 10]. Malignant transformation of ABC is extremely rare [55].

Conflict of Interest Statement

No benefits have been or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject matter of this article.

References

1.

Campanacci M. Aneurysmal bone cyst. In: Campanacci M, editor. Bone and soft tissue tumors. 2nd ed. Padova: Piccin Nuova Libraria; 1999. p. 813–40.CrossRef

2.

Unni KK. Dahlin’s bone tumors: general aspects and data on 11,087 cases. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. p. 382–90.

3.

4.

5.

McQueen MM, Chaimers J, Smith GD. Spontaneous healing of aneurysmal bone cysts. A report of two cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1985;67:310–2.PubMed

6.

7.

Malghem J, Maldague B, Esselinckx NH, De Nayer P, Vincent A. Spontaneous healing of aneurysmal bone cysts: a report of three cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1989;71B:645–50.

8.

9.

Vergel De Dios AM, Bond JR, Shives TC, McLeod RA, Unni KK. Aneurysmal bone cyst. A clinicopathologic study of 238 cases. Cancer. 1992;69:2921–31.PubMed

10.

Ruiter DJ, van Rijssel TG, van der Veide EA. Aneurysmal bone cysts: a clinicopathological study of 105 cases. Cancer. 1977;39:2231–9.PubMed

11.

Mirra JM. Aneurysmal bone cyst. In: Mirra JM, Picci P, Gold RH, editors. Bone tumors. Clinical, radiologic, and pathologic correlations. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1989. p. 1267–311.

12.

Honl M, Westphal F, Carrero V, et al. Pelvic girdle reconstruction based on spinal fusion and ischial screw fixation in a case of aneurysmal bone cyst. Sarcoma. 2003;7(3–4):177–82.CrossRefPubMedPubMedCentral

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree