- Ankle and foot injuries are very common—use OTTAWA rules

- Meticulous assessment essential to avoid disastrous consequences

- Remember 7 review areas in a ‘normal’ radiograph

- CT, MRI or US should be requested where appropriate

Trauma to the ankle and foot is one of the most common reasons that people attend emergency departments. A spectrum of injuries can occur; from sprains through fractures to dislocations. The decision to obtain radiographs is made by careful clinical examination and knowledge of the mechanism of injury. The use of certain guidelines (such as the Ottawa rules, Box 7.1) will exclude serious injuries while reducing unnecessary exposure of the patient to radiation. A higher index of suspicion is needed in elderly.

- Bone tenderness along the distal 6 cm of the posterior edge of the tibia or fibula

- Bone tenderness of the medial or lateral malleoli

- Bone tenderness at the base of the fifth metatarsal or the navicular

- An inability to bear weight immediately or in the emergency department

Injuries of the feet often result in a request for radiographs of the ankle and foot. Clinically, it should be possible to distinguish which area has been injured, and imaging of both is rarely needed. Injuries to the feet, however, often masquerade as ankle injuries.

Anatomy

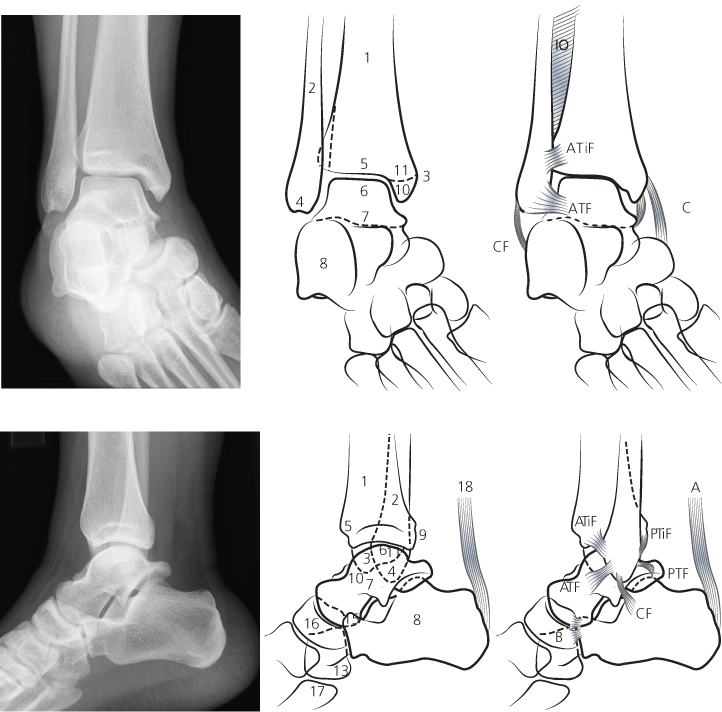

The ankle (Figure 7.1a–f) is a virtual hinge joint shaped as a mortice. The tibia and fibula form a ring with the proximal and distal tibiofibular joints.

The bony structure of the ankle is stabilised by three main groups of ligaments:

- Medial collateral ligament complex (deltoid ligament)

- Lateral collateral ligament, which includes anterior talofibular, posterior talofibular and calcaneofibular ligaments

- Tibiofibular syndesmotic complex.

The talus articulates inferiorly with the calcaneus and anteriorly with the navicular. It is made up of a body, neck, and anterior process and has a fragile blood supply that extends through the ankle joint capsule, which means that fractures of the talar neck may result in avascular necrosis of the body.

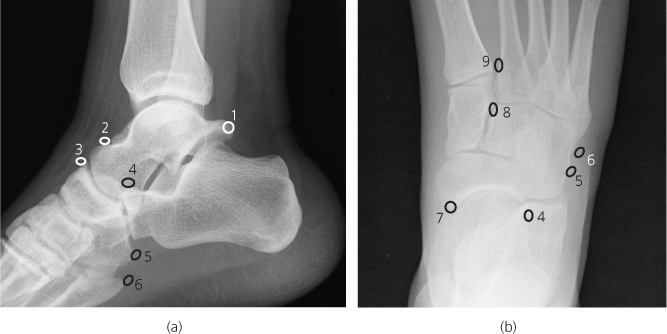

Figure 7.1 (a),(b) AP view of ankle and drawing: (1), Tibia; (2), fibula; 3, medial malleolus; 4, lateral malleolus; 5, plafond; 6, dome; 7, talus; 8, calcaneum; 9, posterior malleolus; 10, anterior colliculus; 11, posterior colliculus. (c) AP ankle ligaments: A, Achilles tendon; ATiF, anterior tibiofibular; ATF, anterior talofibular; B, bifurcate; CF, calcaneofibular; D, deltoid; IO, interosseous; MC, medial collateral; PTiF, posterior tibiofibular; PTF, posterior talofibular. (d),(e) Lat view of ankle and drawing: 1, tibia; 2, fibula; 3, medial malleolus; 4, lateral malleolus; 5, plafond; 6, dome; 7, talus; 8, calcaneum; 9, posterior malleolus; 10, anterior colliculus; 11, posterior colliculus; 12, anterior tubercle; 13, peroneal groove; 14, cuboid; 15, anterior process; 16, navicular; 17, base of fifth metatarsal; 18, Achilles tendon. (f) Lat ankle ligaments.

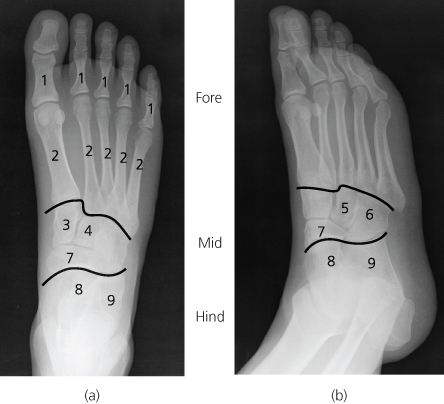

The foot (Figure 7.2a,b) is a complex structure of interdependent bones designed for weight bearing and movement. It can be divided into the forefoot, midfoot, and hindfoot. The joints are complex, but the articular surfaces are parallel and the joint spaces equidistant and symmetrical. Loss of articular parallelism and alteration of joint space width is always abnormal.

Figure 7.2 (a) AP view and (b) oblique view of foot. Forefoot: 1, phalanges; 2, Metatarsals. Midfoot: cuneiforms—3, medial; 4, middle; 5, lateral; 6, cuboid; 7, navicula. Hindfoot: 8, talus; 9, calcaneum.

Normal variants

Radiographs may show variation from the normal anatomy because of the presence of sesamoids, fused or partly fused bones, or accessory ossification centres (Figure 7.3a,b). Although these are normal variants, they can also be the sites of pathology. Commonly occurring ossicles are the os tibiale externum (medial to the navicular), os trigonum (posterior to the talus), and os peroneum (adjacent to the cuboid).

ABCs systematic assessment

- Adequacy

- Alignment

- Bone

- Cartilage and joints

- Soft tissues

Adequacy

Standard imaging of the ankle in the emergency department should include anteroposterior (AP), mortice and lateral projections and for the foot AP, oblique and lateral. Weight-bearing views are better when tolerable. If the pain is in the heel, lateral and axial (Harris) views of the heel are indicated. Advanced imaging should be performed only after consultation with a radiologist.

Figure 7.3 (a),(b) Common accessory ossicles: 1, os trigonum; 2, os supratalare; 3, os supranaviculare; 4, os calcaneum secundarius; 5, os perineum; 6, os vesalaneum; 7, os tibiale externum; 8, os intercuneiforme; 9, os intermetatarseum.

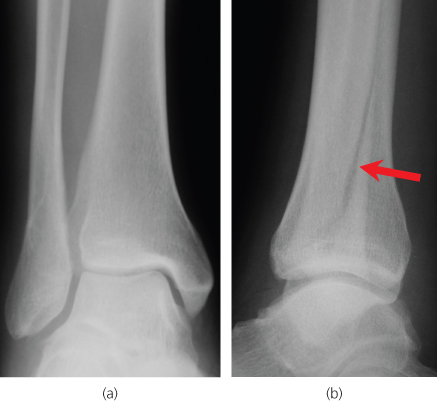

Not all bones and joints will be seen clearly on one view, so multiple views will be needed (Figure 7.4a,b). Some injuries are visualised poorly on radiography, and computed tomography or other types of imaging may be needed (Box 7.2).

Figure 7.4 (a) AP view (right) ‘normal’; (b) lat view—there is clearly an oblique fracture of the fibular shaft only seen in this view (arrow).

- US—Used to assess soft tissues, muscles, tendons and ligaments and for intervention; very operator dependent

- CT—Axial slices obtained with multiplanar reconstruction; good for looking at bones, bone bars and fractures

- MRI—Highly sensitive and specific; shows pathology in bones, joints, and soft tissues; multiplanar imaging, usually axial, sagittal and coronal

- Isotopes—Increase of isotope uptake in bones is a non-specific, highly sensitive indicator of disease

Alignment

On the anteroposterior view, the uniform distance between the tibiotalar and fibulotalar joints should be <4 mm in adults. On the lateral view, the long axis of the tibia and fibula should overlap.

On weight-bearing lateral view radiographs, the superior surfaces of the talus, navicular, medial cuneiform, and first metatarsal lie in a straight line. Böhler’s angle (see Figure 7.18a) lies between the plane of the posterosuperior and anterosuperior surfaces of the calcaneus and measures 28–40° in normal feet. Flattening of the angle (<28°) follows calcaneal compression with trauma.

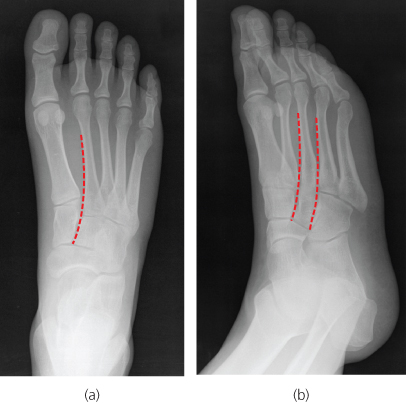

Figure 7.5 The alignment of the midfoot is best assessed on standing views. On the AP (dorsoplantar) view (a) the medial side of the 2nd metatarsal should always align with the medial side of the middle cuneiform. On the AP pronation oblique view (b) the medial side of the 3rd and 4th metatarsal should align with the medial side of the lateral cuneiform and cuboid respectively.

The midtarsal joint separates the talus and calcaneus from the navicular and cuboid and resembles a wave (cyma) on all 3 views of the foot (Figure 7.3a,b). An intact cyma line shows integrity of the midtarsal joints.

The midfoot articulates with the forefoot at the tarsometatarsal joint and must be evaluated carefully, as subluxations of this region can be subtle, and lead to disastrous consequences. In the anteroposterior view of the foot (Figure 7.5a), the medial aspect of the second metatarsal should align with the medial aspect of the middle cuneiform and on the oblique view (Figure 7.5b) the medial aspect of the third metatarsal should align with the medial aspect of the lateral cuneiform and the medial aspect of the fourth metatarsal should align with the medial aspect of the cuboid.

Bone

Trace the cortical margins of the bones. Abnormal steps in the cortex, lucent, or sclerotic lines sometimes indicate the presence of fractures. If no abnormality is seen, check these review areas:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree