Anterior Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome and Other Abnormalities of the Deep Peroneal Nerve

Anatomic Considerations

The common peroneal nerve is one of the two major continuations of the sciatic nerve, the other being the tibial nerve (Fig. 9.1). The common peroneal nerve, which is also known as the common fibular nerve, provides sensory innervation to the inferior portion of the knee joint and the posterior and lateral skin of the upper calf. The common peroneal nerve is derived from the posterior branches of the L4, L5, and S1 and S2 nerve roots. The nerve splits from the sciatic nerve at the superior margin of the popliteal fossa and descends laterally behind the head of the fibula (Fig. 9.2). The common peroneal nerve is subject to compression at this point by circumstances such as improperly applied casts and tourniquets (Fig. 9.3). The nerve is also subject to compression as it continues its lateral course, winding around the fibula through the fibular tunnel, which is made up of the posterior border of the tendinous insertion of the peroneus longus muscle and the fibula itself. Just distal to the fibular tunnel, the nerve divides into its two terminal branches, the superficial and the deep peroneal nerves (Fig. 9.4). Each of these branches is subject to trauma and may be blocked individually as a diagnostic and therapeutic maneuver.

The deep branch continues down the leg in conjunction with the tibial artery and vein to provide sensory innervation to the web space of the first and second toes and adjacent dorsum of the foot (Figs. 9.5 and 9.6). Although this distribution of sensory fibers is small, this area is often the site of Morton’s neuroma surgery and thus is important to the regional anesthesiologist. The deep peroneal nerve provides motor innervation to all of the toe extensors and the anterior tibialis muscles. The deep peroneal nerve passes beneath the dense superficial fascia of the ankle, where it is subject to an entrapment syndrome known as the anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome (Figs. 9.7 and 9.8).

Clinical Correlates

An uncommon cause of dorsal foot pain, anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome is caused by entrapment and compression of the deep peroneal nerve as it passes beneath the superficial fascia of the ankle (Figs. 9.7 and 9.8). Patients suffering from anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome complain of pain, dysesthesias, and numbness of the dorsum of the foot that radiate into the first dorsal web space. The pain associated with anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome may also radiate into the anterior ankle. There is no motor involvement unless the distal lateral division of the deep peroneal nerve is involved. Patients suffering from anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome often report nocturnal foot pain analogous to the nocturnal pain seen in carpal tunnel syndrome sufferers. The patient may report that holding the foot in the everted position may decrease the pain and paresthesia of anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome.

Severe, acute plantar flexion of the foot has been implicated in anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome, as has the wearing of overly tight shoes or squatting and bending forward, as when planting flowers. Tumor, osteophyte, ganglion, and synovitis that have in common their ability to impinge on the deep peroneal nerve such as can cause anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome (Fig. 9.9). Anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome is much less common than posterior tarsal tunnel syndrome.

Patients suffering from anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome will exhibit tenderness on palpation of the deep peroneal nerve at the dorsum of the foot. A positive Tinel’s sign just medial to the dorsalis pedis pulse over the deep peroneal nerve as it passes beneath the fascia usually is present (Fig. 9.10). The pain of anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome may be elicited by active plantar flexion of the affected foot. Weakness of the extensor digitorum brevis may be identified if the lateral branch of the deep peroneal nerve is affected.

Anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome is frequently misdiagnosed as lumbar radiculopathy or diabetic neuropathy or is attributed to primary ankle pathology leading to both diagnostic and therapeutic misadventures. Plain radiographs of the ankle will help identify primary ankle pathology and electromyography will help distinguish the compromise of deep peroneal nerve associated with anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome from radiculopathy (Fig. 9.11). Most patients who suffer from lumbar radiculopathy have back pain associated with reflex, motor, and sensory changes that are associated with back pain, whereas patients with anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome have no

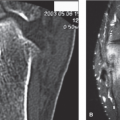

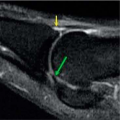

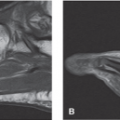

back pain and no reflex changes. Furthermore, the motor and sensory changes of anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome are limited to the distribution of the deep peroneal nerve. Lumbar radiculopathy and deep peroneal nerve entrapment may coexist as the so-called “double crush” syndrome and this can further confuse the clinical picture. Based on the patient’s clinical presentation, additional testing may be indicated, including complete blood cell count, uric acid, sedimentation rate, and antinuclear antibody testing. MRI or CT scanning of the lumbar spine is indicated if a herniated disk, spinal stenosis, or a space-occupying lesion is suspected. MRI and/or ultrasound imaging of the anterior ankle and foot are indicated to confirm the diagnosis of anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome by identifying the pathology responsible for nerve entrapment, for example, tumor, mass, osteophyte, as well as to identify occult pathology (Figs. 9.12 to 9.14).

back pain and no reflex changes. Furthermore, the motor and sensory changes of anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome are limited to the distribution of the deep peroneal nerve. Lumbar radiculopathy and deep peroneal nerve entrapment may coexist as the so-called “double crush” syndrome and this can further confuse the clinical picture. Based on the patient’s clinical presentation, additional testing may be indicated, including complete blood cell count, uric acid, sedimentation rate, and antinuclear antibody testing. MRI or CT scanning of the lumbar spine is indicated if a herniated disk, spinal stenosis, or a space-occupying lesion is suspected. MRI and/or ultrasound imaging of the anterior ankle and foot are indicated to confirm the diagnosis of anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome by identifying the pathology responsible for nerve entrapment, for example, tumor, mass, osteophyte, as well as to identify occult pathology (Figs. 9.12 to 9.14).

FIGURE 9.1 The common peroneal (fibular) nerve is one of the two major continuations of the sciatic nerve, the other being the tibial nerve. The peroneal nerve splits from the sciatic nerve at the superior margin of the popliteal fossa and descends laterally behind the head of the fibula. (From Tank PW, Gest TR. The lower limb. In: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Atlas of Anatomy. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:119.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|