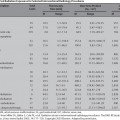

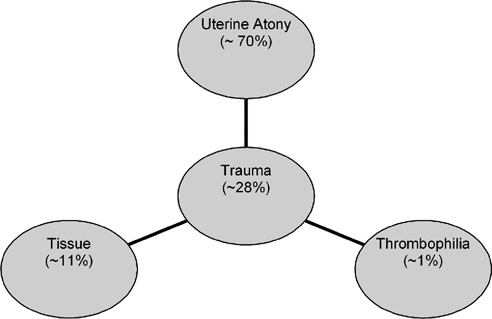

8 Applications of Pelvic Embolization Beyond Uterine Fibroid Embolization Jean-Claude Veille and Gary P. Siskin Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) is the leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality in the world.1 It has been reported to cause at least 17% of maternal mortality in some parts of the world, but this number has been reported as high as over 50%.2–5 In developing countries, PPH is also the most common reason for blood transfusion after delivery.3 Even in developed countries, where maternal morbidity has declined significantly, fatal hemorrhage can still occur when blood or blood components are not readily available or if patients refuse blood products for religious reasons.3,6 In the United States, it has been reported that obstetric hemorrhage is responsible for 13% of maternal death with PPH being the lethal event in more than one-third of these cases.3,5 PPH has been defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as postpartum blood loss >500 cc.7,8 Other definitions using higher volumes of blood before labeling an episode as a PPH have been established based on the fact that the average volume of blood loss at delivery can approach 500 cc.9,10 Some have defined PPH as a 10% change in hematocrit; others define it as postpartum blood loss that requires the patient to have a transfusion.11,12 Postpartum hemorrhage can be classified as either primary PPH, when blood loss occurs during the first 24 hours after delivery, or secondary PPH, when blood loss occurs from 24 hours to 6 weeks after delivery.3 Postpartum hemorrhage is an urgent situation that requires immediate attention. Unfortunately, by the time a significant hemorrhage is recognized the patient is often hemodynamically compromised. Because up to one-fifth of maternal cardiac output, which is >600 mL/minute, enters the uteroplacental circulation at term, it is understandable that primary PPH can be catastrophic, capable of exsanguinating a mother within minutes. Consequences of PPH include a consumptive coagulopathy with disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and multiple organ failure due to circulatory collapse and decreased endorgan perfusion. Primary postpartum hemorrhage occurs in 4 to 6% of pregnancies.12 The most frequent causes are listed in Fig. 8.1 and can be remembered by applying the “Four Ts”: tone (uterine atony), trauma, tissue, and thrombophilia. The main causes of primary PPH are uterine atony, retained placenta or placental fragments, abnormal attachment of the placenta to the inner uterine wall (placenta accreta), and lower genital tract trauma.8,13,14 Uterine atony is the most common cause of PPH and may be responsible for 80% or more of cases.12 Primary PPH due to uterine atony occurs when the relaxed myometrium fails to constrict maternal spiral arteries in the placental bed, which allows for hemorrhage to occur. Abnormal attachment of the placenta is the second most common cause of PPH.15,16 Placenta previa can lead to hemorrhage following removal of the placenta due to the abnormal insertion of its lower edge. When there is invasion of the placenta into the myometrium, the placenta can be difficult to remove. The degree of the abnormal invasion will cause poor hemostasis at that particular site, rendering control of bleeding more difficult. Risk factors for placenta accreta include placenta previa with or without previous uterine surgery, prior myomectomy, prior cesarean delivery, Asherman syndrome, submucosal fibroids, and maternal age older than 35 years.17 When these risk factors are present, one must have a high degree of clinical suspicion for placenta accreta because it is possible to take measures to reduce the likelihood of a significant PPH in these patients. Patients are at increased risk for lower genital tract trauma when there is a difficult cesarean delivery or when there is an instrumented vaginal delivery of the fetus. Hereditary and acquired defects of hemostasis are uncommon causes of PPH as are uterine inversion and uterine rupture.18 Uterine rupture can occur spontaneously or at the site of a previous cesarean delivery or other surgical procedure involving the uterine wall. In addition, abnormal labor and placenta accreta can lead to rupture. Surgical repair is usually required when uterine rupture occurs.8 Uterine inversion, in which the uterine corpus descends to and possibly through the cervix, is associated with PPH as well (Table 8.1). Fig. 8.1 The four Ts summarize the most common causes of postpartum hemorrhage.

Postpartum Hemorrhage

| Uterine atony |

| Retained products of conception |

| Vaginal/cervical laceration |

| Placenta previa |

| Placenta accreta/increta/percreta |

| Placental abruption |

| Uterine fibroids |

Secondary hemorrhage occurs in ~1% of pregnancies.8 Causes of secondary PPH include subinvolution of the placental site, retained products of conception, infection, and inherited coagulation defects.8 Uterine atony, with or without infection, can also contribute to secondary hemorrhage, although bleeding is usually less than that seen with primary PPH. Postpartum hemorrhage may actually be the first indication for von Willebrand disease for many patients. Therefore, some have suggested testing for bleeding disorders in patients with a history of menorrhagia to prepare for this possibility.19

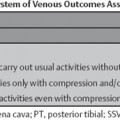

Whenever possible, some of the maternal conditions that potentially could lead to a postpartum hemorrhage should be identified. The most common predisposing conditions are listed in Table 8.2, including nulliparity, maternal obesity, a large baby, prolonged third stage of labor, antepartum hemorrhage, previous postpartum hemorrhage and operative deliveries (especially emergent cesarean sections).14 When these conditions are identified, preparation can take place, which is important for any hospital or medical center managing patients who are at increased risk for this complication. A team can be put in place (e.g., high-risk obstetrics-gynecology, obstetrical anesthesia, interventional radiology, urology, etc.) and there can be regular “drills” involving everybody potentially involved in the care of these patients to enable the team to deliver the best care if this type of event occurs. In our institution, we also have a “postpartum medicinal kit” (Fig. 8.2), which has a seal that can be easily broken at the bedside in the event of a hemorrhagic event. If PPH occurs, this kit, which contains all of the necessary medications to use in this scenario, is therefore immediately available to the care provider. In this way, a PPH is treated as any other “emergency code” in the hospital, which allows our pharmacy department to check these kits on a regular basis for accuracy and expiration. The contents of a typical PPH kit are shown in Fig. 8.3. All of these steps increase the probability that a potentially catastrophic event can be avoided.

| Patients with a previous cesarean scar |

| Patients with a previous myomectomy scar |

| Patients at risk for uterine dehiscence/rupture |

| Leiomyomata uteri |

| Polyhydramnios |

| Multifetal pregnancies (twins or higher order) |

| Prolonged labor |

| Signs of chorioamnionitis |

| Grand multiparity |

| Large fetal weight |

| Diabetes |

| Retained placenta |

| Soft-tissue laceration |

| Episiotomy |

Fig. 8.2 The hemorrhagic kit available in the event of a postpartum hemorrhage.

Fig. 8.3 Contents of the hemorrhagic kit.

Medical Treatment of Postpartum Hemorrhage

Given the possible morbidity and mortality associated with postpartum hemorrhage, an attempt to prevent this is being made with the growing use of active management during the third stage of labor.20 Active management of the third stage of labor is felt to be the best preventive strategy for PPH, with its goal being to hasten and augment uterine contraction and retraction after delivery of the baby and placenta.20–22 The main components of active management include administration of a prophylactic uterotonic agent (typically oxytocin) soon after the delivery of the baby, early clamping and cutting of the umbilical cord, early delivery of the placenta by controlled cord traction after the uterus has contracted, and uterine massage after delivery of the placenta.21,23

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) has recently removed early umbilical cord clamping from its guidelines for active management of the third stage of labor: delaying the clamping can increase iron stores and decrease the incidence of anemia in newborn infants.24 The prophylactic administration of oxytocin has been shown to reduce the rate of postpartum hemorrhage by 40%; this risk reduction can also be seen if oxytocin is given after delivery of the placenta.8,22,25 Several randomized and controlled trials have been performed comparing active with expectant management (allowing the placenta to deliver spontaneously) during the third stage of labor. These trials have found that active management is associated with reduced risks of maternal blood loss, reduced incidence of postpartum anemia, and a reduced requirement for blood transfusions.14,26–28 This has prompted the recommendation that active management should be used routinely in women undergoing a vaginal delivery.20

In the setting of decreased uterine tone (based on physical examination and clinical suspicion), the administration of additional uterotonic medications is considered firstline treatment for PPH.8 Uterotonics (including oxytocin, ergotamines, prostaglandins, and combinations of these medications) have been shown to effectively achieve hemostasis and allow most patients with PPH due to uterine atony to avoid surgery. Hence, the use of these medications has become widespread.3 Interestingly, although a bolus and infusion of oxytocin is considered standard practice in the treatment of PPH, there is little research to support the use of this regimen.29 Initially, 20 to 40 units of oxytocin is administered intravenously. Methergine (methylergonovine; Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Basel, Switzerland) is administered as well if the patient is not hypertensive. Injectable prostaglandins, such as prostaglandin 15-methyl prostaglandin F2-α (carboprost), can also be used, but are associated with significant gastrointestinal side effects. It is often reserved for use only when other measures fail.20,30,31 Misoprostol (Cytotec; Pfizer, Inc., New York, NY) is a synthetic analogue of prostaglandin E1 that has been shown in many randomized, controlled trials to be an effective way to prevent PPH.20,32–35 It is administered rectally or vaginally: the resulting uterine contractility is more potent when compared with the oral route.3 However, recent reviews have shown that misoprostol is not as effective as conventional uterotonics; side effects such as shivering and fever make it less desirable to use.36,37 However, its ease of use and storage relative to conventional medications and its low cost prevent misoprostol from being dismissed as a uterotonic agent.20 Activated Factor VII has also been described as helpful for intractable PPH.38,39 However, because it works on the extrinsic clotting pathway, it may be associated with an increased risk for future thromboembolic events.40 Further studies evaluating the use of Factor VIIa for postpartum hemorrhage are needed to better assess its optimal dose, safety, and effectiveness.41 A summary of the medical treatment for postpartum hemorrhage is given in Table 8.3.

| Oxytocin 40 units/L rapid IV infusion |

| Cytotec 400–1,000µg administered intrarectally |

| 15-Methyl PGF2-α 0.25–1.5 mg IM or intramyometrial (up to 7 ampules) |

| Methylergonovine 0.2 mg IM |

Abbreviations: IM, intramuscular; IV, intravenous; PGF2-α; prostaglandin F2-alpha.

When uterotonics fail to cause sustained uterine contractions and hemorrhage control, packing or tamponade of the uterine cavity can be considered an additional form of conservative management. First, an examination under anesthesia is generally recommended to rule out genital tract lacerations and retained placental fragments.14 Uterine packing with gauze can address PPH, but should only be entertained once a genital tract laceration has been excluded. Packing has been shown to effectively address PPH due to uterine atony, placenta accreta, and placenta previa.14,42 Uterine tamponade may serve to address PPH on an acute basis as well.43 Success has been demonstrated with use of a Foley catheter, a Sengstaken–Blakemore tube, a Rusch urological catheter (which has a larger volume balloon than a Foley catheter), or an SOS Bakri Tamponade Balloon (Cook Medical Inc., Bloomington, IN).13,43,44 The use of topical agents for hemostasis, such as FloSeal (Baxter, Deerfield, IL), has also been described in cases of PPH.45

Surgical Treatment of Postpartum Hemorrhage

When conservative management cannot control a postpartum hemorrhage, a surgical or interventional approach is usually the next line of treatment. The acuity of a patient’s condition and the wishes of a patient to preserve her ability to have other children will help determine whether surgery or interventional treatment is selected. The surgical management of PPH has traditionally relied on hysterectomy and ligation of the internal iliac arteries.13 Today, it is felt that hysterectomy should be reserved for when all other available measures have been exhausted, when persistent or recurrent bleeding following conservative surgical intervention occurs, and when a patient becomes coagulopathic and there is a lack of replacement blood products.13,14

If the uterus is not firm on examination and uterotonics have failed, then consideration can be given toward using the O’Leary technique for ligating the uterine arteries and veins.46 This has shown success for controlling bleeding seen after cesarean sections and is quicker and easier to perform than ligation of the internal iliac arteries.47 Success after ligation of the internal iliac arteries has been described in patients with placenta accreta.48 A B-Lynch suture of the uterus may be attempted as well, especially if bimanual compression of the uterus works to decrease the bleeding.13 This technique involves a pair of vertical brace sutures around the uterus to appose the anterior and posterior walls.13,49 It works by direct application of pressure on the placental bed bleeding and by reducing blood flow to the uterus.8,13 Cho et al50 have also described the use of multiple square suturing to treat an uncontrolled PPH. The technique entails square suturing of the entire uterine wall, including the uterine cavity, around the bleeding area. If the bleeding persists, another square is inserted until the bleeding stops.14 If the uterus is firm on examination, then ligation of the internal iliac or uterine arteries can be considered.13

The presence of a vulvovaginal hematoma, resulting from a significant bleed, can cause patients to be hemodynamically unstable and go into hemorrhagic shock. After placing these patients on prophylactic, broad-spectrum antibiotics, some hematomas can be treated conservatively (if they are small and not expanding); others will have to be treated more aggressively. For large and rapidly expanding hematomas, consideration can be given to incision and drainage. However, this may result in more bleeding from an injured vessel because the “tamponade” created by the large and tense hematoma, has now been “lifted.” On the other hand, once the hematoma has been opened and the clots removed, a bleeding vessel can be potentially identified and ligated. If bleeding is seen, and the vessel cannot be identified, then the patient may require emergent hysterectomy or embolization.

If the above techniques fail to control the bleeding, then a hysterectomy is indicated. Hysterectomy for intractable PPH occurs in 0.5 to 0.8 per 1000 deliveries.5,51 Today, this should be considered the option of last resort in the management of PPH secondary to uterine causes.13 Although a total abdominal hysterectomy can be considered, a supracervical or subtotal hysterectomy is often preferred because it is quicker, simpler, safer, and associated with less blood loss than a total hysterectomy.13,52 Bleeding after hysterectomy will likely require the use of interventional therapy.53

Interventional Treatment of Postpartum Hemorrhage

Since Brown et al54 reported the use of embolization as a treatment option for patients with postpartum hemorrhage in 1979, there have been several reports confirming that this procedure can be an effective way to address the bleeding seen in these patients. Given the anecdotal and literature-based experience that exists surrounding the use of embolization in this setting, it is certainly fair to say that embolization has a role in treating patients with PPH. The questions that come up revolve around the most appropriate timing and indications for the use of embolization in this patient population and with the safety of transferring a patient from labor and delivery to an interventional radiology suite.11 Although some believe that embolization should only be applied in the care of patients failing both medical and surgical management, others believe that obstetrician-gynecologists should turn to embolization once patients fail medical or conservative management.54 This can be done in lieu of surgery or before surgery is performed.55 Still others believe that catheter-based therapy has a role in offering prophylaxis to patients at high risk for postpartum hemorrhage, which can enable the rapid performance of an embolization procedure if needed.

Technically, an angiogram and embolization performed in a patient with postpartum hemorrhage is not significantly different from pelvic embolization procedures performed for other indications. Unilateral femoral access is typically achieved and the internal iliac arteries and subsequently the uterine arteries are selectively catheterized. With the performance of a diagnostic angiogram, it is possible to identify extravasation, pseudoaneurysm formation, or other findings compatible with traumatic injury to the uterine vasculature. Embolization of both uterine arteries is then performed, most commonly with Gelfoam (Pfizer, Inc., New York, NY), until stasis of flow in the target artery is achieved.

The use of coils or polyvinyl (PVA) particles as the embolic agent for this procedure has been reported. Microcoils can be used when there is visible, active bleeding.56 The use of PVA particles has been associated with uterine necrosis after embolization.57 Selective internal iliac angiography and nonselective abdominal aortography are both recommended at some point during these procedures because it is possible that the source of bleeding can be from a vessel other than the uterine artery, including the vaginal, ovarian, and/or inferior epigastric arteries.53,58–60 Once both uterine arteries are embolized, the catheter and sheath are removed and the patient is followed to determine their response to the procedure.

Several articles have been published supporting the use of embolization in this setting. Ojala et al61 found that emergent embolization successfully addressed postpartum bleeding in 75% of patients. In addition, it addressed bleeding in all patients who had persistent bleeding after hysterectomy. In this study, complications associated with emergency embolization included thrombosis of the popliteal artery, vaginal necrosis, and paresthesia of the right leg. Pelage et al reviewed their experience with embolization performed for both primary (n = 27) and secondary (n = 14) PPH.62,63 Bleeding in the secondary PPH group was caused by retained portions of placenta, endometritis, and genital tract tears. Only two patients in the group with primary PPH ultimately required a hysterectomy; no patients with secondary PPH required a hysterectomy after embolization. No complications associated with embolization were reported in either group. Cheng et al64 reported their success with this technique, but also mentioned that repeat embolization was of value in one patient with retained fragments of placenta after delivery.

Several other studies have reported on the success of emergent embolization to treat PPH due to uterine atony, abnormal placentation, and genital tract injuries.65

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree