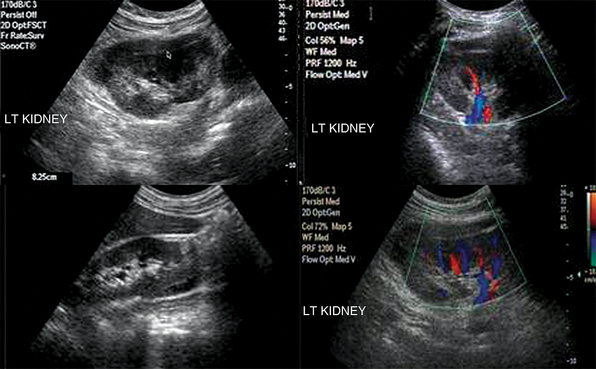

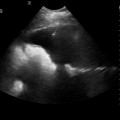

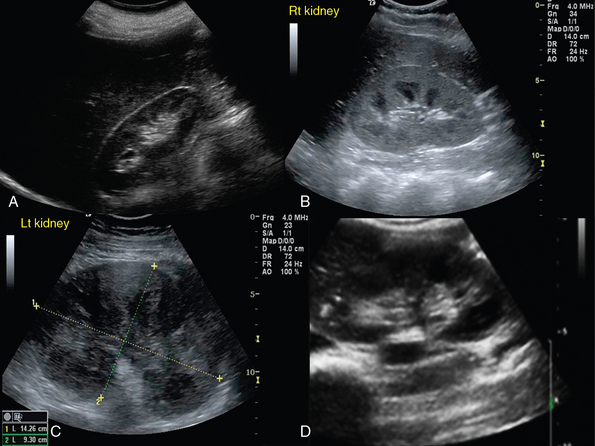

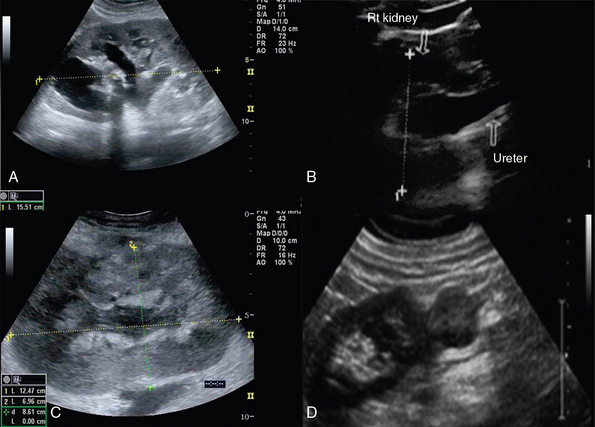

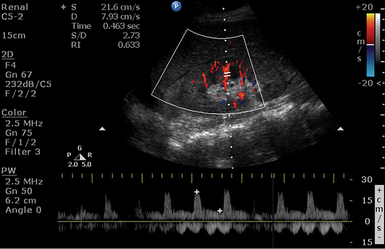

42 The oval-shaped kidneys, measuring 9 to 15 cm in length and 4 to 6 cm in width, are located in retroperitoneum between the 12th thoracic and 4th lumbar vertebrae, just lateral to the psoas muscles. The kidneys are surrounded by the Gerota fascia (echogenic capsule) and a fat layer of variable thickness. Ultrasound examination, in both longitudinal and transverse planes, is performed using convex or microconvex (2.5-5 MHz) transducers and identifies the hilum, containing renal vessels and ureter; the pelvis, receiving two to three major calyces; and the cortex and the medulla, containing renal pyramids. Normal cortical echogenicity should be less than or equal to the echogenicity of liver (Figure 42-1). The right and left kidneys are visualized in the right (midaxillary line) and left (posterior-axillary line) lower intercostal spaces, respectively. The right kidney is lower than the left one because of the right lobe of the liver. In the intensive care unit (ICU), intercostal ultrasound approaches as well as scans along both hypochondriac regions can be used.1–4 Figure 42-1 A, Normal kidney. B, Enhanced cortical echogenicity in lupus-related glomerulonephritis. C, Kidney enlargement with loss of parenchymal differentiation in a septic patient with acute kidney injury. D, Heterogeneous cortical appearance in pyelonephritis. The right and left main renal arteries (RAs) originate laterally from the abdominal aorta, inferior to the superior mesenteric artery (SMA). Segmental (lobar) arteries originate before or immediately after entering the kidney, and their branches (interlobar arteries) travel through the kidney parenchyma. The right and left renal veins (RV) originate off the inferior vena cava (IVC). Ureters travel retroperitoneally, crossing over the iliac vessels and along the pelvic sidewalls, before curving anteriorly and medially at the level of ischial spines, and thus entering the bladder at ureterovesical junction. Ureters are not well visualized by ultrasound but, when distended (hydroureter), appear as hypoechoic, tubular structures (Figure 42-2). The round-shaped bladder is depicted by ultrasound just above the pubis. When not distended, its wall appears thickened. When fully distended, its wall should measure less than 0.4 cm thick. The trigone is a triangular region of the bladder base, formed by two ureteral orifices and the internal urethral orifice, which are identified by depicting ureteral jets, emanating from the ureters. In critical care patients, the balloon of the Foley catheter should be visible in the bladder (catheter is clamped to avoid bladder emptying, Figure 42 E-1). Inability to visualize the balloon should prompt a search for its location because extravesical inflation may result in local trauma and confusing appearances. The normal adult testis measures about 3 to 4 cm (longitudinal section) and is normally hypoechoic. The upper testicular pole is capped with the head of the epidydimis. A thin rim of anechoic fluid may be seen around the testicle.1–4 Figure 42-2 Hydronephrosis. A, Kidney enlargement with dilatation of the collecting system. B, Distended ureter. C, Parenchyma of mixed echogenicity (edema-hemorrhage) in renal trauma. D, Renal cell carcinoma projecting from the lower kidney pole. Renal failure resulting from various causes is commonly encountered in the ICU. Ultrasound may depict loss of parenchymal differentiation and rule out obstruction. In acute failure, kidneys may appear normal or increased in size (see Figure 42-1), whereas in chronic failure, kidneys appear small with thin parenchyma and irregular borders. The Doppler-derived resistive index [(RI) = (peak systolic velocity − end diastolic velocity)/(peak systolic velocity)] of renal and interlobar arteries has been used to study many different renal diseases. The normal mean RI value is approximately 0.60, whereas values greater than 0.8 indicate parenchymal disease. These criteria require further validation, and inaccurate readings may occur, especially in ICU patients. Doppler measurements may be obtained when the sample volume is adjusted to 1.5 to 2 mm and the angle to 0 degrees when evaluating interlobar arteries, whereas the angle should be 60 degrees or less in the RA. Despite its limitations, the above method may be promising in the monitoring of critical care patients with failing renal function (Figure 42 E-2).4–8 Figure 42 E-2 A septic patient presented with “anuric” acute kidney injury. Doppler-derived resistive index (RI) (0.63 in this image) values ranged from 0.45 to 0.65 in repeated measurements. After supportive therapy, renal function and urine output gradually normalized. Pyelonephritis, although difficult to diagnose in the ICU because of blurred clinical picture, may be detected by ultrasound (see Figure 42-1). Ultrasonographic findings are a normal or enlarged kidney, focal or diffuse swelling with decreased echogenicity, loss of corticomedullary differentiation, areas of necrosis (hypoechoic), and microabscess formation (hypoechoic areas with smooth or irregular margins and high-level internal echoes). Renal abscess appears usually as a complex, lobulated cystic mass, whereas hyperechoic foci within indicate presence of gas. Depiction of gas bubbles extended to parenchymal areas, sinus, and perinephric space characterize a severe form of pyelonephritis called emphysematous pyelonephritis, which is usually observed in diabetic patients. Another form of severe infection is pyonephrosis, which may appear as calyceal dilatation (hydronephrosis) with the presence of echogenic material within, consistent with pus or debris formation.4 Glomerulonephritis is a major cause of end-stage kidney disease. In acute and subacute cases, kidneys may appear enlarged because of parenchymal swelling with increased echogenicity and prominent hypoechoic medullary pyramids (see Figure 42-1). In chronic glomerulonephritis, kidneys are small and atrophic with increased echogenicity.4 Renal trauma is usually observed after abdominal injury (see Figure 42-2). Although ultrasound can detect hemoperitoneum, its role in evaluating renal trauma is limited compared with computed tomography (CT). Ultrasound may detect presence of parenchymal (mixed echogenicity) or subcapsular hematomas (perirenal fluid collection), segmental corticomedullary dedifferentiation, linear defect consistent with laceration, or a shattered kidney (multiple areas of disorganized tissue with blood and urine collections) (Figure 42 E-3). Trauma may lead to persistent urine leakage and development of urinomas that manifest as delayed complications (e.g., hydronephrosis, paralytic ileus, etc.). Urinomas have a variety of appearances and may be misdiagnosed as ordinary ascites, abdominal or pelvic abscesses or hematomas, cystic masses, or pancreatic pseudocysts. Urinomas may result from blunt or penetrating trauma, iatrogenic injury, or transmitted back pressure caused by downstream obstruction resulting from a ureteral stone, surgical ligature, or abdominal and pelvic masses. Ureteral urine leaks may be iatrogenic (e.g., surgery or endourologic procedures).9

Approach to the urogenital system

Anatomy

Disorders

Kidney

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Approach to the urogenital system