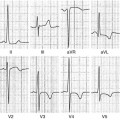

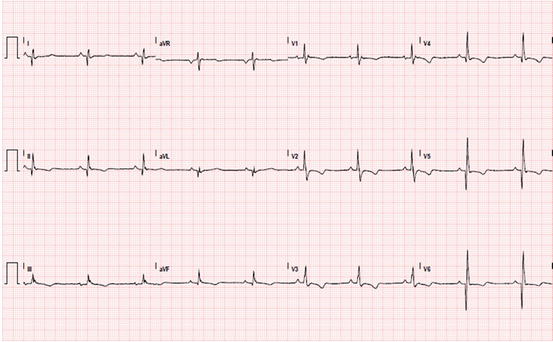

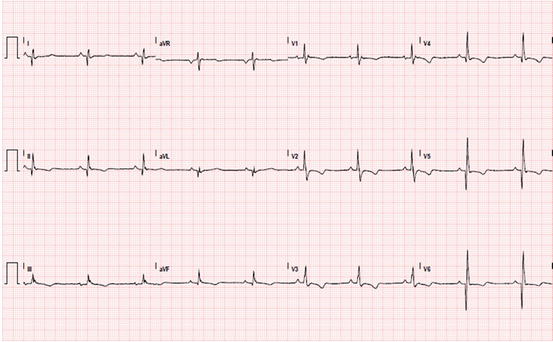

Fig. 14.1

Typical electrocardiogram (ECG) in advanced arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC). Right atrial enlargement, low QRS voltages, epsilon waves, and negative T waves in anterior precordial leads are present

Table 14.1

Revised Task Force Criteria 2010

Major criteria | Minor criteria | |

|---|---|---|

RV systolic function and structure | By 2D echo: | By 2D echo: |

Regional RV akinesia, dyskinesia, or aneurysm and one of the following (end diastole): | Regional RV akinesia, dyskinesia, or aneurysm and 1 of the following (end diastole): | |

PLAX RVOT ≥32 mm, | PLAX RVOT ≥29 to <32 mm, | |

PSAX RVOT ≥36 mm, or fractional area change ≤33 % | PSAX RVOT ≥32 to <36 mm, or fractional area change >33 to ≤40 % | |

By MRI: | By MRI: | |

Regional RV akinesia, dyskinesia or aneurysm or dyssynchronous RV contraction and one of following: | Regional RV akinesia, dyskinesia or aneurysm or dyssynchronous RV contraction and 1 of the following: | |

Ratio of RV end-diastolic volume to BSA ≥110 ml/m2 or ≥100 ml/m2 (or RVEF ≤40 %) | Ratio of RV end-diastolic volume to BSA ≥100 to <110 ml/m2 (male) or ≥90 to <100 ml/m2 (female) or RV >40 to ≤45 % | |

By RV angiography: | By RV angiography: | |

Regional RV akinesia, dyskinesia, or aneurysm | Regional RV akinesia, dyskinesia, or aneurysm | |

Tissue characterization | Residual myocytes <60 % by morphometric analysis, with fibrous replacement of the RV free wall myocardium in ≥1 sample, with or without fatty replacement of tissue on EMB | Residual myocytes 60–75 % (or 50–65 % if estimated), with fibrous replacement of RV free wall myocardium in ≥1 sample, with or without fatty replacement of tissue on EMB |

Repolarization abnormality | Inverted T waves in right precordial leads (V1–3) or beyond in individuals >14 years of age (in the absence of complete RBBB QRS ≥120 ms | Inverted T waves in leads V1 and 2 in individuals >14 years (in absence of complete RBBB) or in V4–6 or inverted T waves in leads V1–4 in individuals >14 years (in presence of complete RBBB) |

Depolarization abnormality | Epsilon waves in the right precordial leads (V1–3) | Late potential by SAECG in ≥1 of 3 parameters in absence of QRS duration ≥110 ms on standard ECG; filtered QRS duration ≥114 ms; terminal QRS duration <40 μV or ≥38 ms; root-mean-square voltage of terminal 40 ms ≤20 μV; QRS terminal activation duration ≥55 ms measured from S-wave nadir to end of QRS |

Arrhythmias | Nonsustained or sustained ventricular tachycardia of LBB morphology with superior axis | Nonsustained or sustained ventricular tachycardia of RV outflow configuration, LBB morphology with inferior axis, or >500 ventricular extrasystoles per 24 h (Holter) |

Frequent ventricular extrasystoles (>1,000 per 24 h) (Holter) | ||

Familial history | ARVC confirmed pathologically in the first degree or identification of a pathogenic mutation categorized as associated or probably associated with ARVC | History of ARVC in a first-degree relative or premature sudden death (<35 years) due to suspected ARVC or ARVC confirmed pathologically, or by Task Force Criteria in second-degree relative |

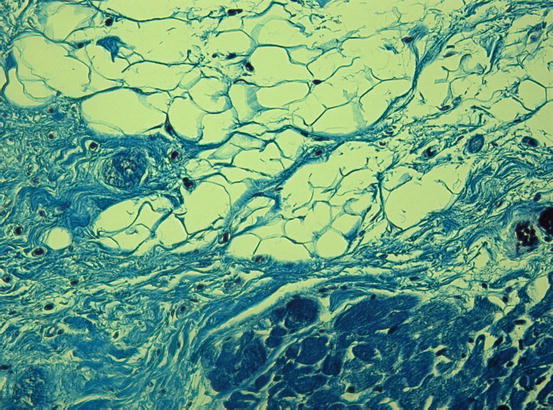

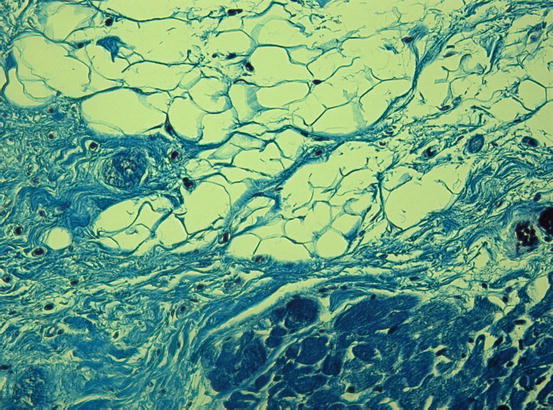

Diagnosis of ARVC remains a clinical challenge, particularly in its early stages and in patients with minimal echocardiographic RV abnormalities and especially in the absence of structural changes in the typical triangle of dysplasia [subtricuspid region, RV outflow tract (OT), and RV inferoapical region] [12]. Positive endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) of the RV is a recognized gold standard, but it often yields a false-negative result (sensitivity ~67 %) because of the frequently localized fibroadipose infiltration. Consequently, the best approach in making a diagnosis of ARVC is by combining different diagnostic tests [9, 13]. The histological hallmark of the disease is fibrofatty infiltration of the RV myocardium with areas of surviving myocytes (Fig. 14.2) and sometimes inflammatory infiltration. Pathologic abnormalities can progress with time, typically starting from the epicardium and eventually extending down to reach the subendocardium and becoming transmural. This implies a weakness and thinning of the free wall, resulting in RV dilatation and aneurysm formation, bulges, and sacculations, which constitute the typical diagnostic findings on noninvasive imaging tests [14].

Fig. 14.2

Histologic specimen (Azan Mallory, ×20) at the right ventricular level in a case of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC). Severe fatty infiltration associated with patchy and interstitial fibrosis (blue) is present

LV involvement, typically affecting the posterior and lateral walls, is present in more than half of ARVC cases [15, 16]. The frequent, and sometimes predominant, LV involvement suggests that ARVC is not a unique entity but a complex disease, with three possible patterns of expression: classic right-dominant (39 % of cases), left-dominant arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (LDAC) (5 %), and biventricular (56 %) forms [17, 18]. Interestingly, recent data showed that the LV may be affected not only in the late stage of the disease but may also occur in absence of alterations in RV systolic dysfunction, characterizing the LDAC form of the disease [16]. This left-dominant pattern is characterized by predominant LV involvement (dilation, systolic impairment, LGE) exceeding that of the RV or in the presence of preserved RV function [19]. Other features of this pattern are the LV origin of arrhythmias (RBBB morphology), inferolateral T-wave inversion on ECG (Fig. 14.3), and family history of LDAC.

Fig. 14.3

Electrocardiogram (ECG) of a patient with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy with biventricular involvement. Sinus rhythm; epsilon waves in V1; inverted T waves in right precordial leads; negative T waves from V4 to V6 and inferior leads; deep Q waves in inferolateral leads

14.3.1 Differential Diagnosis

Diagnosis of ARVC should be considered in any patient who does not have known heart disease and who presents with frequent premature ventricular contractions or symptomatic ventricular tachycardia. The main differential diagnoses include the following conditions:

1.

Idiopathic RV outflow tract/ventricular tachycardia is a mostly benign condition that is not associated with structural heart disease. In its early stage, ARVC can be difficult to distinguish from this idiopathic type of ventricular arrhythmia in the absence of structural changes. Differential diagnosis is based on the fact that this arrhythmia is nonfamilial, and patients do not have the characteristic ECG/signal average ECG abnormalities of ARVC (inversion T waves in V1–V3, epsilon waves, QRS duration >110 ms) (Table 14.2) [20].

Table 14.2

Clinical expressions of RVOT VT and ARVC

RVOT VT | ARVC | |

|---|---|---|

Age at onset | Third or fifth decade of life | Third or fourth decade of life |

Sex | Females predominantly | Males predominantly |

Family history | − | + |

Reports of SD | − | + |

12-lead ECG | Normal | T-wave inversion in precordial leads V1–5 |

Prolongation of QRS complex in leads V1 or V2 | ||

Epsilon waves observed | ||

SAECG | Normal | Late potentials observed |

ECHO | Normal | Structural and wall motion abnormalities of RV |

Arrhythmias | PVCs, repetitive monomorphic VT, induced/sustained VT | PVCs, SVT, NSVT, VF |

Origin of arrhythmia | Septum | Parietal wall |