CHAPTER 6 This chapter gives an overview of radiologic evaluation of arthritis with the caveat that it is, by necessity, a simplified version and in no way complete. If one is interested in greater detail or more accuracy, I would urge reading either Debbie Forrester’s excellent monograph1 on the subject or Anne Brower’s superb book.2 The definitive work on this subject is Don Resnick’s six-volume tome,3 but most can’t read even the arthritis portion during a 4-year residency—it’s best used as a reference. In general, if the distribution of the arthropathy can be determined, the differential diagnosis becomes very short (Table 6-1). Although on paper this sounds quite nice, it can on occasion be difficult to accurately determine the distribution of the arthropathy. The distribution of the arthropathy is difficult to determine when it is not clearly distal or proximal but is more general, such as occurs with gout and sarcoid. It can also be difficult to accurately determine the distribution when advanced disease is present, such as occurs with severe rheumatoid arthritis. With severe rheumatoid arthritis the proximal nature of the pathology is not so apparent because of involvement with the metacarpophalangeal joints and even the phalangeal joints. In a similar manner, when psoriatic disease, Reiter’s syndrome, or osteoarthritis is severely advanced, it can involve the more proximal portion of the hand and wrist, although this is unusual. TABLE 6-1 Arthropathy Distribution in Hands and Wrists Side-to-side symmetry of the arthropathy is occasionally helpful in selecting a differential diagnosis (Box 6-1). Primary osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis are classically described as bilaterally symmetric. Exceptions occur quite often, however, so bilateral symmetry in these disorders is probably only on the order of 80% to 90%. Rheumatoid arthritis is a common offender of the bilateral symmetry rule, and one should not be surprised if rheumatoid arthritis is seen to be asymmetric in up to 25% of cases. Involvement of joints other than the hand and wrist is not a common feature with most of the arthritides. In general, when a large joint such as the shoulder, hip, or knee is involved with arthritis only a few entities need to be considered (Table 6-2). Although it must be emphasized that almost any arthritis can affect almost any joint, the diseases listed in Table 6-2 probably will account for 90% or more of the large joint arthropathia. TABLE 6-2 Involvement of certain joints can often give a clue as to the underlying disease process. For example, if the sacroiliac (SI) joints are involved, the differential diagnosis is as listed in Table 6-3. Again, almost any arthritis can affect any joint, but if the SI joint is involved, using Table 6-3 for the differential diagnosis will give a 95% or better chance of having the right answer. TABLE 6-3 The aforementioned differential diagnoses are to be considered generalizations and are, for the most part (except when mentioned), probably not more than 75% to 85% accurate. They are a nice starting point, however, for developing the differential diagnosis. I cannot overemphasize that the exceptions are exceedingly common. There are probably more missed diagnoses in the field of arthritis than in almost any other area of radiology. The remainder of this chapter gives a brief overview of arthritides with which most radiologists should be familiar. Rather than provide an in-depth description of each process—which can be obtained in any of the major radiology texts—I give salient discriminating points that might make it easier to differentiate one process from another. The most common arthritis seen by radiologists is osteoarthritis, or degenerative joint disease (DJD). It is thought to be caused by trauma—either overt or as an accumulation of microtrauma over the years. The hallmarks of DJD are joint space narrowing, sclerosis, and osteophytosis (Box 6-2 and Figure 6-1). If all three of these findings are not present on the radiograph, another diagnosis should be considered. FIGURE 6-1 The only disorder that will cause osteophytes without sclerosis or joint space narrowing is diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH). This common bone-forming disorder is seen primarily in the spine and at first glance resembles DJD except there is no disc space narrowing and there is no sclerosis (Figure 6-2). DISH is not thought to be caused by trauma or stress, as is DJD, and is not painful or disabling, as DJD can be. Millions of dollars per year are awarded to government employees on retirement for “disability” payments for supposed DJD acquired on their jobs when, in fact, they have DISH and are misdiagnosed. It is hoped that such errors will be rectified in the future as more radiologists become informed of the difference between DJD and DISH. FIGURE 6-2 Primary osteoarthritis is a familial arthritis that affects middle-aged females almost exclusively and is seen only in the hands. It affects the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints, the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints, and the base of the thumb in a bilaterally symmetric fashion (Figure 6-3). If the arthritis is not bilaterally symmetric, the diagnosis of primary osteoarthritis should be questioned (Figure 6-4). FIGURE 6-3 FIGURE 6-4 A type of primary osteoarthritis that can be very painful and debilitating is erosive osteoarthritis. It has the identical distribution as mentioned for primary osteoarthritis but is associated with severe osteoporosis of the hands as well as erosions. It is somewhat uncommon, and radiologists generally see little of this disorder. Residents tend to mention erosive osteoarthritis in every example of joint erosions encountered whether it is in the hands, knees, hips, or wherever. This is totally inappropriate because erosive osteoarthritis occurs only in the hands, and there it has a characteristic distribution, which should make for an easy diagnosis. There are a few exceptions to the classic triad of findings seen in DJD (sclerosis, narrowing, and osteophytes). Several joints also exhibit erosions as a manifestation of DJD. I call these joints the letter joints because they are all often called by their initials: the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), the acromioclavicular (AC) joint, and the SI joints; the symphysis pubis behaves similarly (Box 6-3). When erosions are seen in one of these joints DJD must be considered; otherwise, inappropriate treatment can occur (Figure 6-5). FIGURE 6-5 Another process that can occasionally be seen in DJD is a subchondral cyst or geode (taken from the geologic term used when a volcanic rock has a gas pocket that leaves a large cavity in the rock). Geodes are cystic formations that occur around joints in a variety of disorders (Box 6-4). Presumably, one method by which they form is synovial fluid being forced into the subchondral bone, causing a cystic collection of joint fluid. They seldom cause problems by themselves but are often misdiagnosed as something more sinister (Figure 6-6; see Chapter 4). FIGURE 6-6 Rheumatoid arthritis is a connective tissue disorder of unknown cause that can affect any synovial-lined joint in the body. The radiographic hallmarks are soft tissue swelling, osteoporosis, joint space narrowing, and marginal erosions (Box 6-5). In the hands it is classically a proximal process that is bilaterally symmetric (Figure 6-7). There are so many exceptions to these rules, however, that I have come to regard them as no better than 80% accurate. Rheumatoid arthritis has a large variety of appearances and can be difficult to diagnose with any degree of assurance from its radiographic appearance alone. FIGURE 6-7 Rheumatoid arthritis in large joints is fairly characteristic in that it causes a lot of joint space narrowing and is associated with marked osteoporosis. Erosions may or may not be present and tend to be marginal, that is, away from the weight-bearing portion of the joint. In the hip the femoral head tends to migrate axially, whereas in osteoarthritis it tends to migrate superolaterally (Figures 6-8 and 6-9). In the shoulder the humeral head tends to be “high-riding” (Figure 6-10). Other things to think of when confronted with a high-riding shoulder are a torn rotator cuff and calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystal deposition disease (CPPD) (Box 6-6). FIGURE 6-8 FIGURE 6-9 FIGURE 6-10 When rheumatoid arthritis is long-standing, it is not unusual for secondary DJD to superimpose itself on the findings one would expect with rheumatoid. This picture of DJD differs somewhat from that usually seen in that the sclerosis and osteophytes are considerably diminished in severity as compared with the joint space narrowing (Figure 6-11). FIGURE 6-11 A group of diseases that was formerly called rheumatoid variants is now known as the seronegative HLA-B27-positive spondyloarthropathies. What was wrong with rheumatoid variants? It was short and concise. It has been replaced with a polysyllabic mouthful that is perhaps more descriptively correct, but so what? That’s the problem with most academicians—make it sound more erudite and maybe everyone will think we’re smarter than we really are. They shouldn’t be so insecure. I liked rheumatoid variants. One of the more characteristic findings is that of syndesmophytes in the spine. A syndesmophyte is a paravertebral ossification that resembles an osteophyte except that it runs vertically, whereas an osteophyte has its orientation in a horizontal axis. Sometimes deciding whether a particular paravertebral ossification is an osteophyte or a syndesmophyte is difficult based on its orientation alone (Figure 6-12). Bridging osteophytes and large syndesmophytes can have a similar appearance, with both having an orientation halfway between vertical and horizontal. How should one evaluate those examples? Easy—ignore them. Look at the other vertebral bodies and use the ossifications on them to determine whether you are dealing with osteophytes or syndesmophytes. If no other level is involved, you might just have to make the diagnosis based on something else. In other words, sometimes you simply will not be able to tell one from the other. Osteophytes should be accompanied by disc space narrowing (except in DISH), but sometimes narrowing in not obvious. FIGURE 6-12 Syndesmophytes are classified as to whether they are marginal and symmetric or nonmarginal and asymmetric. A marginal syndesmophyte has its origin at the edge or margin of a vertebral body and extends to the margin of the adjacent vertebral body. Marginal syndesmophytes are invariably bilaterally symmetric as viewed on an anteroposterior (AP) spine film. Ankylosing spondylitis classically has marginal, symmetric syndesmophytes (Figure 6-13). Inflammatory bowel disease has an identical appearance when the spine is involved. FIGURE 6-13 Nonmarginal, asymmetric syndesmophytes are generally large and bulky. They emanate from the vertebral body away from the end-plate or margin and are unilateral or asymmetric as viewed on an AP spine film (Figures 6-12 and 6-14). Psoriatic arthritis and Reiter’s syndrome classically have this type of syndesmophyte. FIGURE 6-14 Involvement of the SI joints is common in the HLA-B27 spondyloarthropathies. The patterns of involvement, like the patterns of involvement of the spine, are somewhat typical for each disorder. Ankylosing spondylitis and inflammatory bowel disease typically cause bilaterally symmetric SI joint disease that is initially erosive and progresses to sclerosis and fusion (Figures 6-15 and 6-16). It is extremely unusual to have asymmetric or unilateral SI joint disease in these two disorders. Another entity that can have bilateral SI joint erosions is hyperparathyroidism. Subperiosteal resorption along the SI joints mimics erosive changes. This is more commonly seen in children.

Arthritis

Distal

Proximal

Psoriasis

Reiter’s syndrome

Osteoarthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis

Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystal deposition disease (CPPD)

Ankylosing spondylitis

Osteoarthritis (degenerative joint disease)

Pigmented villonodular synovitis

Synovial osteochondromatosis

Infection

Rheumatoid arthritis

Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystal deposition disease (CPPD)

Ankylosing spondylitis

Osteoarthritis (degenerative joint disease)

Inflammatory bowel disease

Psoriasis

Reiter’s syndrome

Infection

Gout

Osteoarthritis

Degenerative joint disease of the shoulder. This former professional baseball pitcher with long-standing shoulder pain has joint space narrowing, subchondral sclerosis, and osteophytosis, which are hallmarks of degenerative joint disease (DJD).

Degenerative joint disease of the shoulder. This former professional baseball pitcher with long-standing shoulder pain has joint space narrowing, subchondral sclerosis, and osteophytosis, which are hallmarks of degenerative joint disease (DJD).

Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis. A lateral film of the lumbar spine shows extensive osteophytosis without significant disc space narrowing or sclerosis. This is a classic picture for diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH).

Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis. A lateral film of the lumbar spine shows extensive osteophytosis without significant disc space narrowing or sclerosis. This is a classic picture for diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH).

Primary osteoarthritis. A radiograph of the left (A) and right (B) hands in a patient with primary osteoarthritis shows classic findings of osteophytosis, joint space narrowing, and sclerosis at the distal interphalangeal joints, the proximal interphalangeal joints, and the base of the thumb. This is bilaterally symmetric in this patient, which is typical for primary osteoarthritis.

Primary osteoarthritis. A radiograph of the left (A) and right (B) hands in a patient with primary osteoarthritis shows classic findings of osteophytosis, joint space narrowing, and sclerosis at the distal interphalangeal joints, the proximal interphalangeal joints, and the base of the thumb. This is bilaterally symmetric in this patient, which is typical for primary osteoarthritis.

Lack of bilateral symmetry in primary osteoarthritis. This patient has classic radiographic findings of primary osteoarthritis in the left hand; however, the right hand shows only osteoporosis and soft tissue wasting without evidence of osteoarthritis. The reason for the lack of bilaterality is that this patient has long-standing right-sided paralysis, which has blocked the onset of the arthritic changes in the right hand.

Lack of bilateral symmetry in primary osteoarthritis. This patient has classic radiographic findings of primary osteoarthritis in the left hand; however, the right hand shows only osteoporosis and soft tissue wasting without evidence of osteoarthritis. The reason for the lack of bilaterality is that this patient has long-standing right-sided paralysis, which has blocked the onset of the arthritic changes in the right hand.

Osteoarthritis of the SI joint. A young woman, who is a professional dancer, complained of left-sided hip pain. This anteroposterior (AP) film of the pelvis demonstrated left SI joint sclerosis, joint irregularity, and erosions. A complete workup to rule out an HLA-B27 spondyloarthropathy was negative, and no laboratory or clinical evidence for infection was found. Her clinical history pointed to this process being completely occupation related, and an aspiration biopsy to rule out infection was therefore not performed. This is not an unusual appearance for DJD of the SI joints.

Osteoarthritis of the SI joint. A young woman, who is a professional dancer, complained of left-sided hip pain. This anteroposterior (AP) film of the pelvis demonstrated left SI joint sclerosis, joint irregularity, and erosions. A complete workup to rule out an HLA-B27 spondyloarthropathy was negative, and no laboratory or clinical evidence for infection was found. Her clinical history pointed to this process being completely occupation related, and an aspiration biopsy to rule out infection was therefore not performed. This is not an unusual appearance for DJD of the SI joints.

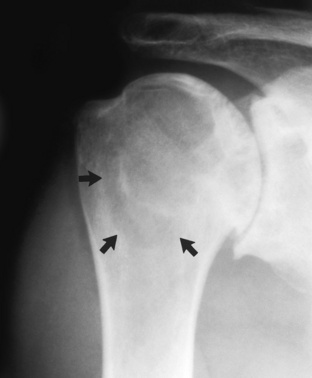

Subchondral cyst or geode of the shoulder. This patient has marked DJD of the shoulder with joint space narrowing, sclerosis, and osteophytosis. A large lytic process (arrows) seen in the humeral head is a subchondral cyst or geode, which often occurs in association with DJD. Because of the DJD in the shoulder, a biopsy to rule out a more sinister lesion in the humeral head should be avoided.

Subchondral cyst or geode of the shoulder. This patient has marked DJD of the shoulder with joint space narrowing, sclerosis, and osteophytosis. A large lytic process (arrows) seen in the humeral head is a subchondral cyst or geode, which often occurs in association with DJD. Because of the DJD in the shoulder, a biopsy to rule out a more sinister lesion in the humeral head should be avoided.

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis. An erosive arthritis that primarily affects the carpal bones and the metacarpophalangeal joints is seen that has osteoporosis and soft tissue swelling (note the soft tissue over the ulnar styloid processes). It is bilaterally symmetric process in this patient, which is classic.

Rheumatoid arthritis. An erosive arthritis that primarily affects the carpal bones and the metacarpophalangeal joints is seen that has osteoporosis and soft tissue swelling (note the soft tissue over the ulnar styloid processes). It is bilaterally symmetric process in this patient, which is classic.

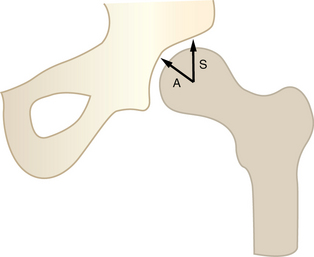

Routes of migration of the femoral head. Osteoarthritis of the hip tends to cause superior (S) migration of the femoral head in relation to the acetabulum, whereas rheumatoid arthritis tends to cause axial (A) migration of the femoral head in relation to the acetabulum.

Routes of migration of the femoral head. Osteoarthritis of the hip tends to cause superior (S) migration of the femoral head in relation to the acetabulum, whereas rheumatoid arthritis tends to cause axial (A) migration of the femoral head in relation to the acetabulum.

Rheumatoid arthritis of the hip. Note the severe joint space narrowing in this patient with rheumatoid arthritis. The femoral head has migrated in an axial direction with fairly concentric joint space narrowing. Minimal secondary degenerative changes have occurred, as noted by the sclerosis in the superior portion of the joint; however, these have been diminished somewhat by the osteoporosis that usually accompanies rheumatoid arthritis.

Rheumatoid arthritis of the hip. Note the severe joint space narrowing in this patient with rheumatoid arthritis. The femoral head has migrated in an axial direction with fairly concentric joint space narrowing. Minimal secondary degenerative changes have occurred, as noted by the sclerosis in the superior portion of the joint; however, these have been diminished somewhat by the osteoporosis that usually accompanies rheumatoid arthritis.

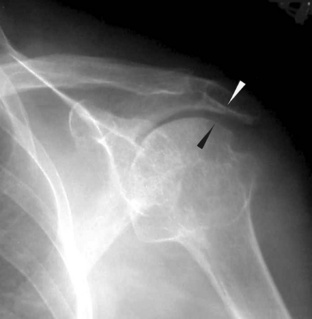

Rheumatoid arthritis in the shoulder. An AP view of the shoulder in this patient with rheumatoid arthritis shows that the distance between the acromion and the humeral head is diminished (arrows). Ordinarily this space is about one fingerbreadth in width to allow the rotator cuff to move freely. This is a common finding in rheumatoid arthritis as well as in CPPD or with a torn rotator cuff.

Rheumatoid arthritis in the shoulder. An AP view of the shoulder in this patient with rheumatoid arthritis shows that the distance between the acromion and the humeral head is diminished (arrows). Ordinarily this space is about one fingerbreadth in width to allow the rotator cuff to move freely. This is a common finding in rheumatoid arthritis as well as in CPPD or with a torn rotator cuff.

Secondary degenerative disease in the knee in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. This patient has a history of long-standing rheumatoid arthritis. An AP view of the knee shows severe osteoporosis and joint space narrowing. Secondary DJD is occurring, as evidenced by the sclerosis and osteophytosis; however, these findings are out of proportion to the severe joint space narrowing. When DJD narrows a joint to this extent, the osteophytosis and sclerosis are invariably much more pronounced.

Secondary degenerative disease in the knee in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. This patient has a history of long-standing rheumatoid arthritis. An AP view of the knee shows severe osteoporosis and joint space narrowing. Secondary DJD is occurring, as evidenced by the sclerosis and osteophytosis; however, these findings are out of proportion to the severe joint space narrowing. When DJD narrows a joint to this extent, the osteophytosis and sclerosis are invariably much more pronounced.

HLA-B27 spondyloarthropathies

Psoriasis with syndesmophytes. The large paravertebral ossification on the left side of the T12–L1 disc space (open arrow) is difficult to differentiate between an osteophyte and a syndesmophyte. Either could have this appearance. However, the paravertebral ossification at the left L1–2 disc space (solid arrow) definitely has a vertical rather than a horizontal orientation, as does the faint ossification seen at the T11–12 disc space (small arrow). These definitely represent syndesmophytes. Therefore it makes sense to logically assume that the ossification at the T12–L1 disc space is almost certainly a syndesmophyte as well. This patient has large nonmarginal asymmetric syndesmophytes, which are typical of psoriatic arthritis or Reiter’s syndrome. This patient indeed has psoriasis.

Psoriasis with syndesmophytes. The large paravertebral ossification on the left side of the T12–L1 disc space (open arrow) is difficult to differentiate between an osteophyte and a syndesmophyte. Either could have this appearance. However, the paravertebral ossification at the left L1–2 disc space (solid arrow) definitely has a vertical rather than a horizontal orientation, as does the faint ossification seen at the T11–12 disc space (small arrow). These definitely represent syndesmophytes. Therefore it makes sense to logically assume that the ossification at the T12–L1 disc space is almost certainly a syndesmophyte as well. This patient has large nonmarginal asymmetric syndesmophytes, which are typical of psoriatic arthritis or Reiter’s syndrome. This patient indeed has psoriasis.

Marginal symmetric syndesmophytes in a patient with ankylosing spondylitis. Bilateral marginal syndesmophytes are seen bridging the disc spaces throughout the lumbar spine in this patient. This is a “bamboo spine” and is classic for ankylosing spondylitis or inflammatory bowel disease.

Marginal symmetric syndesmophytes in a patient with ankylosing spondylitis. Bilateral marginal syndesmophytes are seen bridging the disc spaces throughout the lumbar spine in this patient. This is a “bamboo spine” and is classic for ankylosing spondylitis or inflammatory bowel disease.

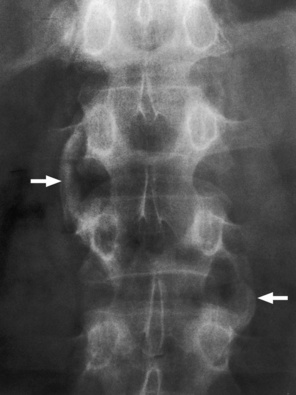

Syndesmophytes in psoriatic arthritis. Large, bulky, nonmarginal asymmetric syndesmophytes (arrows) are seen in this patient with psoriatic arthritis.

Syndesmophytes in psoriatic arthritis. Large, bulky, nonmarginal asymmetric syndesmophytes (arrows) are seen in this patient with psoriatic arthritis.

Arthritis