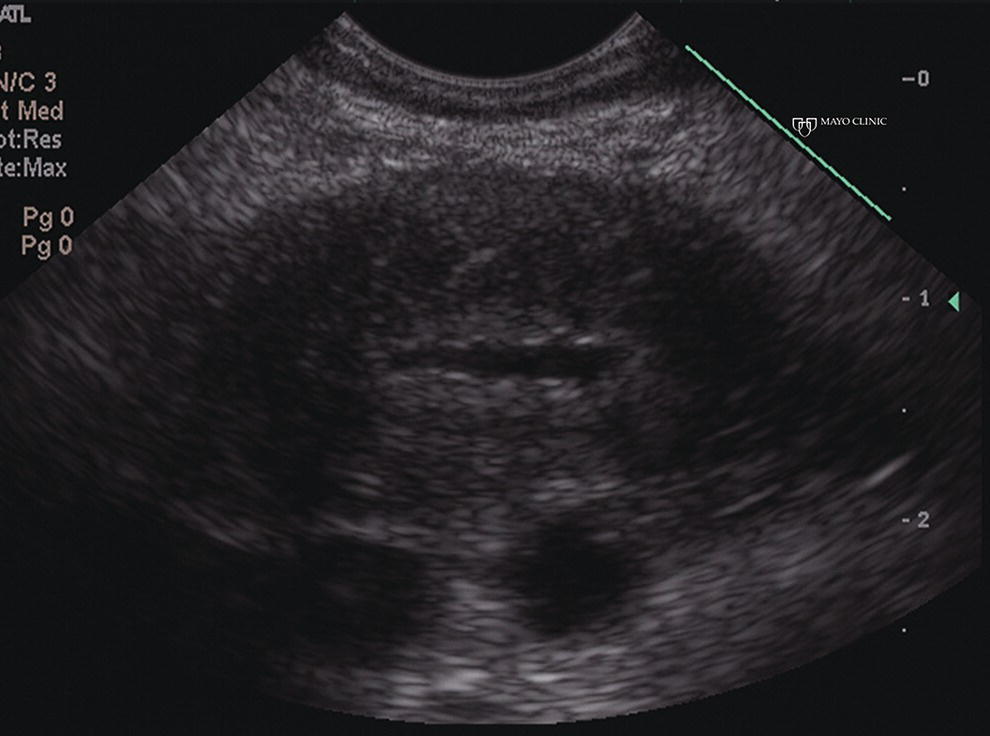

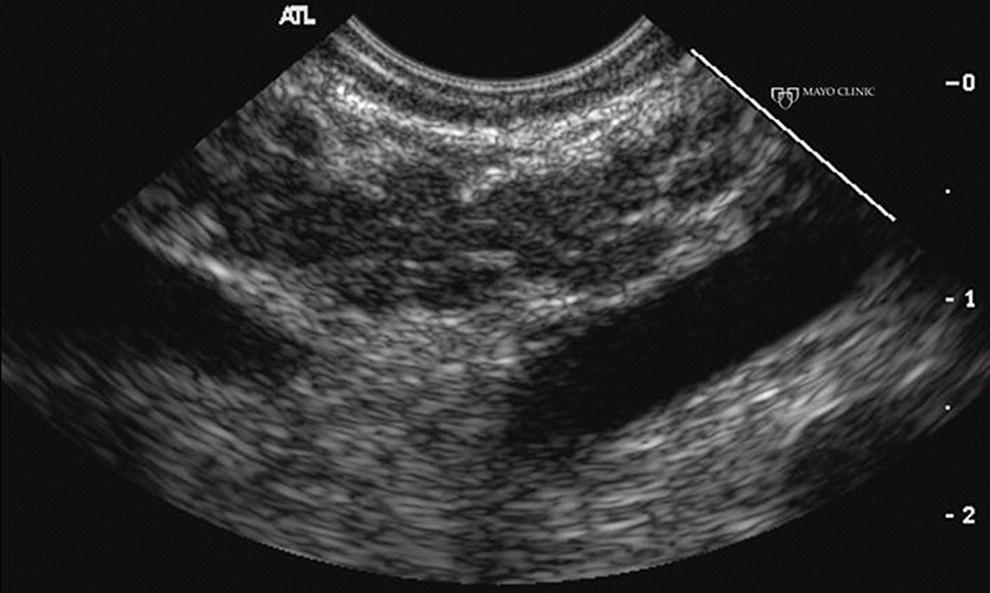

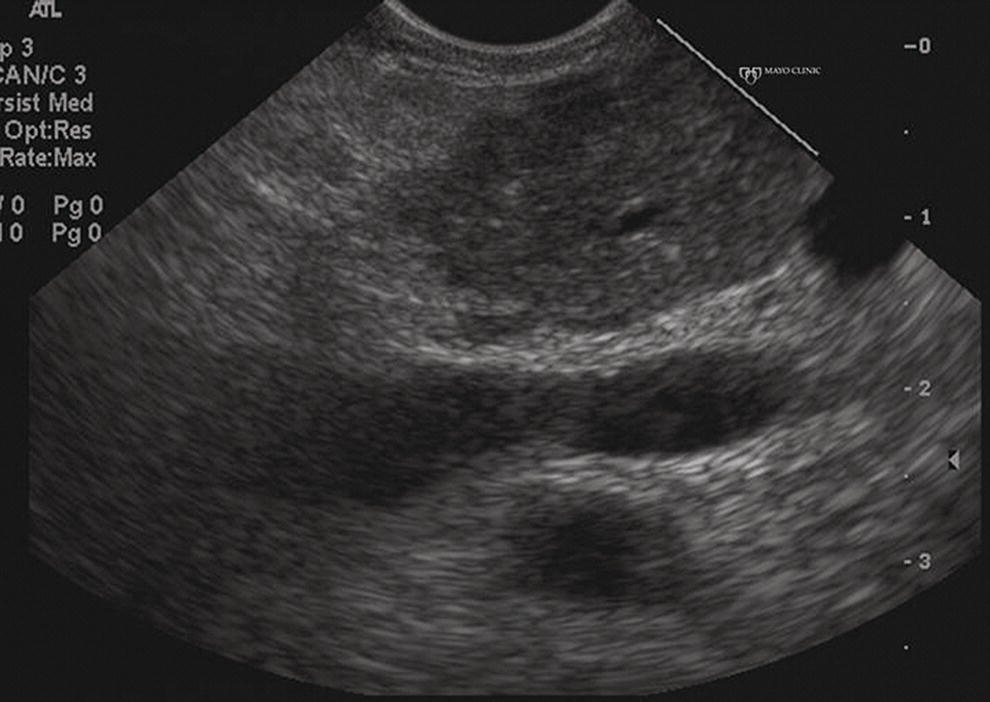

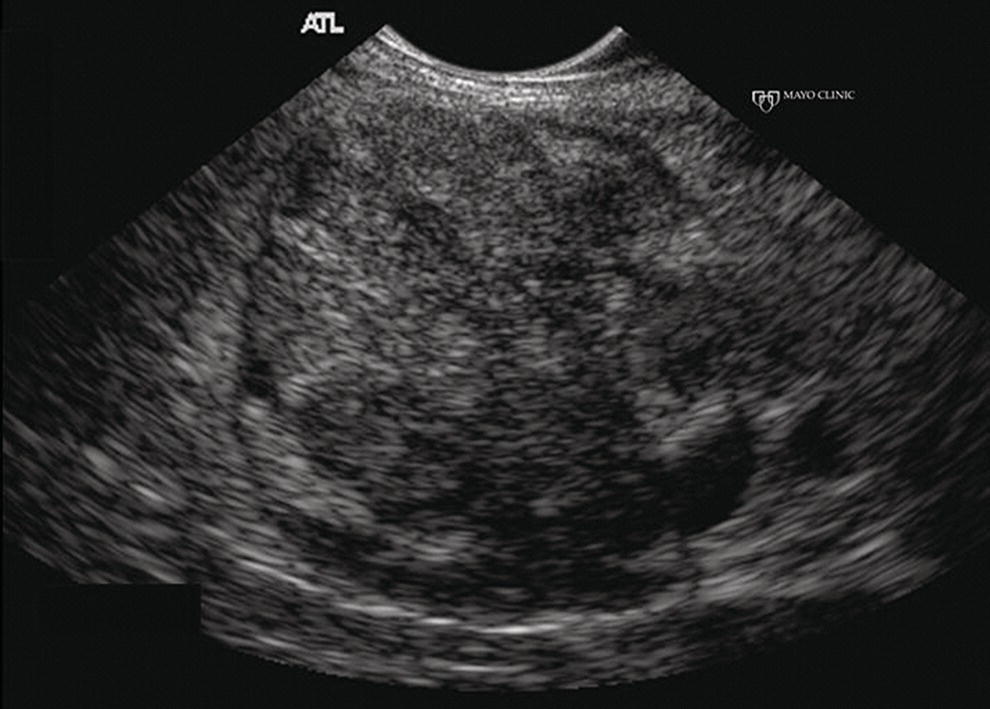

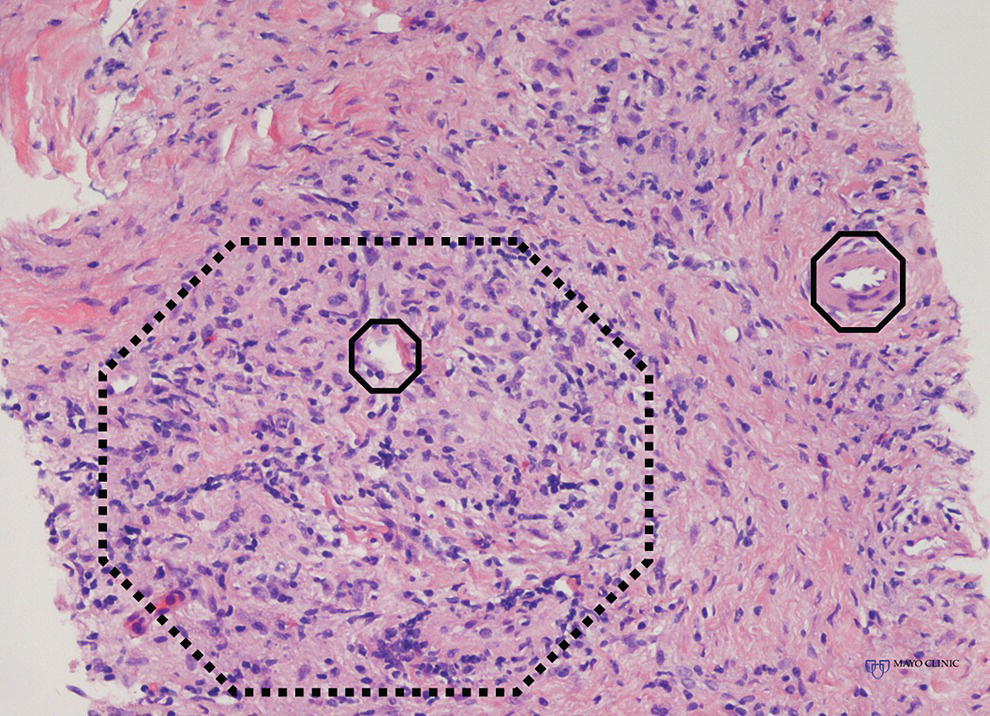

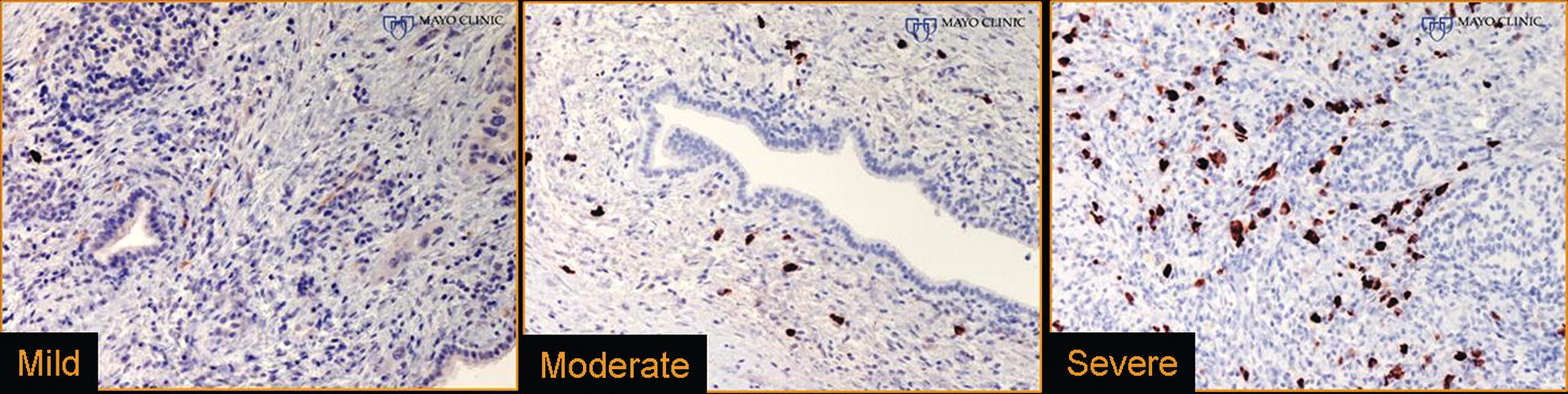

Larissa Fujii‐Lau1, Michael J. Levy2, and Suresh T. Chari3 1 University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI, USA 2 Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA 3 MD Anderson Cancer Hospital, Houston, TX, USA While the first description of autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) was by Sarles et al. in 1961, the term “autoimmune pancreatitis” was first introduced by Yoshida et al. in 1995. There are two types of AIP, type 1 being the classic AIP described from Japan. Type 1 AIP is part of a systemic fibro‐inflammatory process that afflicts multiple organs including pancreas, bile duct, retroperitoneum, lymph nodes, salivary glands, and kidneys which demonstrate a characteristic IgG4‐rich lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate. Type 2 AIP appears to be a pancreas‐specific disorder, sometimes associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Both forms readily respond to steroid therapy. Type 2 can only be definitively diagnosed on histology. The initial description of AIP highlighted the presence of obstructive jaundice secondary to a pancreatic head mass mimicking pancreatic cancer. As clinical experience evolved there came a greater understanding of the diverse clinical, laboratory, and histologic manifestations of AIP, leading the way to more comprehensive diagnostic criteria such as the Mayo HISORt system that considers the findings of histology, imaging, serology, other organ (non‐pancreatic) involvement, and response to steroid therapy. Similarly, international consensus diagnostic criteria (ICDC) for the diagnosis of AIP incorporate five features, including imaging characteristics of the pancreatic parenchyma and duct (obtained with cross‐sectional imaging or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography), serology, other organ involvement, pancreatic histology, and response to steroids. While pancreatic imaging is a key component of the diagnostic systems, notably absent in both criteria is specific mention of the role for endoscopic ultrasound (EUS). This omission of EUS from diagnostic algorithms likely results from the lack of meaningful studies that document the EUS imaging features and a paucity of data pertaining to the utility and safety of EUS‐guided fine needle aspiration (EUS‐FNA) and EUS‐guided fine needle biopsy (EUS‐FNB) in this patient cohort. Our aim is to review the spectrum of AIP features identified by EUS and suggest a potential role of EUS‐guided tissue sampling. The classic EUS finding in AIP is diffuse (sausage‐shaped) pancreatic enlargement with a hypoechoic, coarse, patchy, heterogeneous appearance (Figures 24.1–24.3). When all of these classic features are present, there is a high likelihood of AIP. However, there may be significant overlap between the appearance of AIP and other pancreatic disorders. EUS may reveal isolated or multiple mass lesions that can mimic “unresectable” carcinoma (Figure 24.4). Other less common EUS features include glandular atrophy, calcification, cystic spaces, features of usual chronic pancreatitis, or even a normal gland (Figure 24.5). Unfortunately, there are no pathognomonic EUS findings for AIP. While a few features of AIP are characteristic, none are adequate to allow definitive diagnosis of AIP and their presence in other pancreatic disorders is common. The lack of pathognomonic features and diverse spectrum of EUS findings somewhat limits the utility of EUS imaging alone. This has driven the pursuit of safe and reliable methods for obtaining tissue to enhance diagnostic accuracy. As the biliary tree is the most common extrapancreatic organ involved in AIP, it should be thoroughly evaluated during EUS when AIP is suspected. Wall thickening of either the bile duct or gallbladder may be appreciated by EUS. Figure 24.1 Classic endoscopic ultrasound appearance of autoimmune pancreatitis including hypoechoic diffuse (sausage‐shaped) pancreatic enlargement with hypoechoic, coarse, patchy, heterogeneous parenchyma. Figure 24.2 Almost classic endoscopic ultrasound appearance of autoimmune pancreatitis with a hypoechoic gland and coarse, patchy, heterogeneous changes without glandular enlargement. Although the use is not widespread, some image‐enhancing techniques employed during EUS may be used to help differentiate AIP from pancreatic cancer. In one study on the use of elastography in AIP, five patients with focal AIP were found to have a homogeneous stiff (blue) pattern in the mass and throughout the entire pancreas, which differed from pancreatic cancer or normal pancreas in which the pancreatic parenchyma was predominantly of intermediate stiffness (green). Using contrast‐enhanced EUS, AIP has been shown to be associated with hypervascularity within the mass‐like lesion and the surrounding pancreatic parenchyma as compared to pancreatic cancer where the mass is hypovascular in comparison to the surrounding pancreatic tissue Figure 24.3 Almost classic endoscopic ultrasound appearance of autoimmune pancreatitis with a hypoechoic and enlarged gland without the prominent coarse, patchy, heterogeneous changes. Figure 24.4 Endoscopic ultrasound finding of a mass‐like lesion in a patient with autoimmune pancreatitis that may be confused with an “unresectable” pancreatic ductal carcinoma. As the EUS features of AIP overlap with other diseases of the pancreas, tissue sampling has an important role in the evaluation of AIP. Cytologic specimens obtained during EUS‐FNA of the pancreas are often inadequate for diagnosing AIP. Typically, a definitive diagnosis requires pancreatic core biopsy obtained at surgery under CT guidance, or by EUS‐FNB. Some suggest that the main role of EUS‐FNA is to exclude pancreatic adenocarcinoma rather than to diagnose AIP. However, this opinion needs to be viewed with caution due to a 10–40% false‐negative rate in the diagnosis of cancer using EUS‐FNA. Figure 24.5 Endoscopic ultrasound features of nonspecific chronic pancreatitis in a patient with autoimmune pancreatitis. To overcome the inadequate samples obtained at EUS‐FNA, larger‐caliber cutting biopsy needles have been created in which the goal is to obtain samples with preserved tissue architecture. One of the original needles was the Tru‐cut biopsy (TCB) needle. Although no longer available, we have previously demonstrated that EUS‐TCB acquires core specimens with preserved tissue architecture permitting histologic diagnosis of AIP similar to the results using other EUS‐FNB needles. In updating our initial report, 48 patients (38 male, 10 female; mean age 59.7 years [range 18–87]) with a final diagnosis of AIP have undergone a mean of 2.9 EUS‐TCB tests (range 1–7). Autoimmune pancreatitis was histologically diagnosed on EUS‐TCB in 35 (73%) patients and the diagnostic sensitivity varied from 33 to 90% among the five endosonographers. Nondiagnostic cases were found to have chronic pancreatitis (n = 8), nonspecific histology (n = 2), and failed tissue acquisition (n = 3). Thirty‐seven patients underwent EUS‐FNA (mean 3.4 passes, range 1–7 passes) that failed to establish or suggest the diagnosis in any patient. Complications of EUS‐TCB included mild transient abdominal pain (n = 3) and self‐limited intraprocedural bleeding (n = 1). No patient required hospitalization or therapeutic intervention. The diagnosis of AIP was strongly suspected prior to EUS in 14 patients as a result of their clinical, laboratory, imaging, and laboratory findings. For 22 patients the diagnosis was considered pre‐EUS as part of a broader differential, and in 12 patients the EUS appearance alone led to the initial suspicion of AIP. Serum IgG4 was more than twice the upper limit of normal in only 23% of patients. No patient with EUS‐TCB diagnosis of AIP required surgery. In the patients with false‐negative EUS‐TCB, the diagnosis was made by HISORt criteria. Over a mean follow‐up of 2.6 years no false‐negative diagnoses of pancreatic cancer were identified. Our experience demonstrates that large‐caliber pancreatic biopsy is safe and provides sufficient material to definitively diagnose AIP, obviating the need for surgical resection. Figure 24.6 Histologic examination of endoscopic ultrasound‐guided Tru‐cut biopsy (EUS‐TCB) specimen reveals an intact artery seen at the right of the image (single solid marker). In addition, an intense infiltration by lymphocytes and histiocytes results in near complete obliteration of the vein (obliterative phlebitis) shown at the left of the image (dashed marker surrounding solid marker). H&E, original magnification ×300. Recently, more studies have emerged using other EUS‐FNB needles in the diagnosis of AIP. However, larger studies and a comparative study of EUS‐FNA and EUS‐FNB is likely required to understand the role of EUS tissue acquisition in the diagnosis of AIP. Histologic features of type 1 AIP (lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis, LPSP) include a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate that surrounds medium‐ and large‐size interlobular pancreatic ducts, and pancreatic venules (obliterative phlebitis) while sparing arterioles, as well as swirling fibrosis centered around pancreatic ducts (storiform fibrosis) (Figure 24.6). Histology accurately distinguishes AIP from other causes of chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma. IgG4 immunostaining of tissue samples identifies IgG4‐positive plasma cells and the presence of moderate (11–30 cells per high‐power field [HPF]) or severe (>30 cells/HPF) infiltration is considered diagnostic (Figure 24.7). These findings distinguish AIP from alcohol‐induced pancreatitis and the peritumoral inflammation associated with carcinoma. Histologic features of type 2 AIP (idiopathic duct‐centric pancreatitis, IDCP) include a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate with granulocyte epithelial lesions with partial/complete duct obstruction. Tissue immunostaining in IDCP is typically negative, but may reveal mild (1–10 cells/HPF) or moderate (11–20 cells/HPF) IgG4‐positive plasma cell infiltration. Figure 24.7 IgG4 immunostaining of the Tru‐cut biopsy specimen reveals the findings of mild infiltration (1–10 plasma cells per high‐power field [HPF]), moderate infiltration (11–30 cells/HPF) and severe infiltration (>30 cells/HPF). The difficulty in diagnosing AIP highlights the need for improved understanding of its EUS imaging features and the development of reliable and safe methods for acquiring core tissue specimens. Until such time, EUS will have a central role in the evaluation of AIP in a minority of centers. We advocate EUS imaging to provide supportive evidence for or against an AIP diagnosis. Because imaging alone cannot firmly establish the diagnosis, FNA is often necessary to exclude underlying malignancy. We recommend EUS‐FNB for patients with a compatible clinical presentation in whom there is diagnostic uncertainty and when the findings are likely to alter management. This recommendation assumes the reliable and safe us of EUS‐FNB. Further study is necessary to help clarify the diagnostic accuracy and role of EUS imaging and tissue sampling in this patient cohort.

24

Autoimmune Pancreatitis

Introduction

Endoscopic ultrasound imaging (Video 24.1)

Image‐enhancing techniques during EUS

EUS‐FNA and EUS‐FNB

Histologic features

Summary

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree