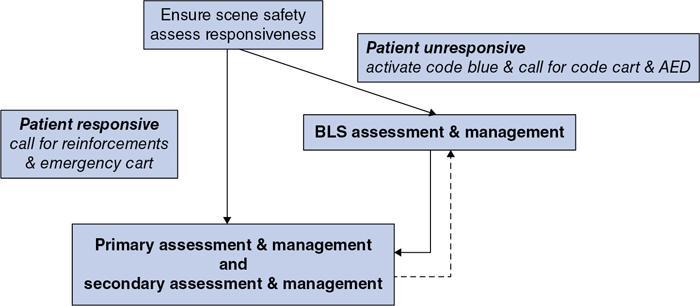

Sunil Kumar, Bhavna Saxena, Neera Gupta Kumar, Rakesh Kumar Radiology departments play host to a wide variety of patients for both diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. These may range from otherwise healthy trauma victims with serious injuries undergoing diagnostic procedures to patients with preexisting comorbidities undergoing therapeutic interventional procedures. A high-risk situation seen within radiology suites is the occurrence of contrast media-induced reactions with varying degrees of severity, which may be serious enough to progress to cardiac arrest. Regardless of the severity, such situations demand immediate action and prompt treatment to prevent poor and potentially catastrophic outcomes for the patient, the highest chance of survival being possible only if cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is begun within 2 minutes of cardiac arrest by well-trained healthcare provider (HCP). It is therefore essential that all clinical staff posted in radiology have basic resuscitation skills which are regularly updated. The recommendations of the ILCOR (International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation) are the basis of the guidelines recommended by most international resuscitation organizations such as the European Resuscitation Council (ERC), the American Heart Association (AHA), the Australian and New Zealand Committee on Resuscitation (ANZCOR), the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada (HSFC), etc. The recommendations adopted by the AHA are commonly accepted and followed worldwide and will be the basis of the recommendations in this chapter. The following is an example of a patient brought to the radiology suite and the possible scenarios, which we may encounter within the context of adverse reactions of varying degrees of severity right up to the life-threatening ones. A 62-year-old male with history of carcinoma pancreas is brought to the radiology suite for a contrast-enhanced CT scan of the abdomen. He is given IV contrast. Scenario 0 is the commonest and is probably the reason that when any of the other scenarios occur, there is discomfort to chaos in the radiology suite! The detailed management of these adverse events (Scenarios 1–2) is mentioned elsewhere in this book. In this chapter, we will be using a systematic approach to these events, an approach that is simple and protocol-based. Using a universal, protocol-based approach or a common language of assessment and management helps in minimizing errors and decreases the likelihood of missing out critical steps, thereby leading to a better outcome. The systematic approach to an adverse event as suggested by the American Heart Association (AHA) requires the HCP to first determine the level of consciousness of the patient after ensuring scene safety (Fig. 1.17.1). Prior to approaching any patient, scene safety must be ensured, both for the HCP and for the patient. This means safety measures taken to prevent transmission of diseases, based on the assumption that all body fluids of a patient which the HCP may come in contact with, might be infectious. These universal precautions include the use of some or all of the personal protective equipment (PPE) such as gloves, masks, gowns or specialized clothing, face shields, and protective eyewear, depending upon the need. In the context of the radiology work environment, it also includes ensuring safety regulations such as strict zone restrictions for the use of ferromagnetic objects in magnetic resonance suites. Once the level of consciousness is ascertained, the HCP calls for reinforcements and the emergency cart or code cart as he prepares for further management, which depends upon whether the patient is responsive or unresponsive. If the patient is conscious and responsive (scenarios 1 and 2), the systematic approach prompts the HCP to conduct the primary and secondary assessment and management. If, on the other hand, the patient is unresponsive (scenario 3), the HCP immediately begins the BLS assessment and management first, followed by primary and secondary assessment and management. At any time during primary and secondary assessment and management, if a responsive patient becomes unresponsive, BLS assessment and management is immediately initiated (Fig. 1.17.1). Before we discuss the application of these approaches in context of adverse events in radiology, let us review these approaches. If the patient is conscious and responsive (scenarios 1 and 2), the systematic approach prompts the HCP to ask for reinforcements along with emergency cart and then conduct a series of assessment and management steps called the primary and secondary assessment and management. These can be conducted one after the other or simultaneously, depending upon the availability of HCPs. The reinforcements summoned for a responsive patient who has had an adverse event are called rapid response team (RRT) in many centres. The primary assessment and management employs the ABCDE approach, i.e., assessment and management of Airway, Breathing, Circulation, Disability and Exposure. It is carried out by assessing each component and taking action simultaneously by different members of the team of HCPs. The secondary assessment and management involves finding out the underlying cause(s) for the adverse condition so as to address reversible factors as early as possible. The underlying condition is looked for by structured history taking and exploring the most common known causes for adverse condition. The components of ABCDE approach for primary assessment and management are Airway, Breathing, Circulation, Disability and Exposure. The details of these components are described as follows: Airway: If bag-mask ventilation is adequate, then it is recommended to continue with the same. SADs and ETT have to be used when bag-mask (with or without adjuncts) is not enough to keep the airway patent. Endotracheal intubation is done if there is return of spontaneous circulation and the patient remains unconscious or needs respiratory support. However, there are some exceptions to this rule. Early intubation is recommended if airway obstruction is due to anaphylaxis or inhalational burn injuries. Placement of an advanced airway requires confirmation of its correct placement, which is done by physical examination and quantitative waveform capnography (end-tidal CO2). Subsequently, the airway device must be properly secured and monitored to prevent dislodgement. Breathing: Circulation: Disability: Exposure: Open the airway using manoeuvres and/or adjuncts, or medication Provide supplementary oxygen and support ventilation, as needed Provide high-quality compressions, if in arrest Stabilize unstable condition by appropriate measures Manage deteriorating neurological status as required. If becomes unresponsive, add BLS assessment and management Manage as required Adapted from M.W. Donnino, K. Navarro, K. Berg, S.C. Brooks, J. Crider, et al and AHA ACLS Project Team. Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support (ACLS) Provider Manual, American Heart Association, 2016, Dallas, Texas. The secondary assessment and management goes hand-in-hand with the primary assessment and management with the aim to facilitate diagnosing the cause(s) of the patient’s condition (or change in condition) and to help in fine-tuning its management. Secondary assessment has two components: structured history taking in an organized way and sifting through the usual and most frequently encountered cause(s) for sudden adverse condition in patients. Structured history taking: Sifting through the most frequently encountered cause(s):

1.17: Basic and advanced life support

The systematic approach

Patient conscious and responsive

Details of primary and secondary assessment and management

Component

Assessment of

Management

Airway

Patency of the airway

Breathing

Adequacy of ventilation and oxygenation

Circulation

Quality of compressions (if in arrest). Haemodynamic status if circulation present (heart rate and rhythm; BP; peripheral perfusion, etc.)

Disability

Neurological functions

Exposure

Anything missed. Cover after assessment

Secondary assessment and management

COMPONENT CONSISTS OF

SAMPLE history

H’s and T’s

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Basic and advanced life support

Summary of the Steps of Secondary Assessment and Management. The Aim is To Facilitate Diagnosing The Cause(S) of Patient’s Condition (Or Change in Condition) and Help in Fine-Tuning the Management