and Siddharth P. Jadhav2

(1)

Department of Radiology, University of Texas Medical Branch Pediatric Radiology, Galveston, TX, USA

(2)

The Edward B. Singleton Department of Pediatric Radiology, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, TX, USA

Abstract

This chapter presents a review of the battered child syndrome/non-accidental trauma. Emphasis will be on how to evaluate the various injuries with the given history and to know which injuries/fractures are highly suspicious.

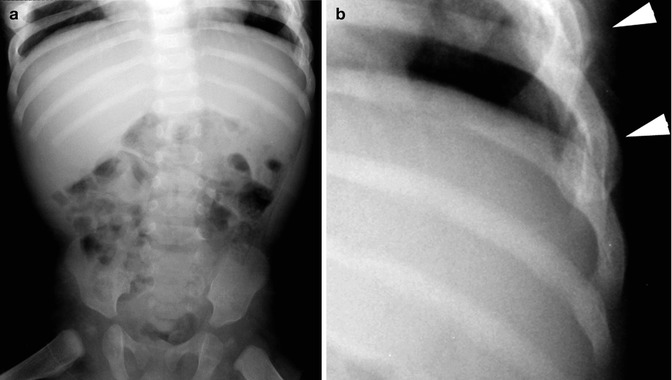

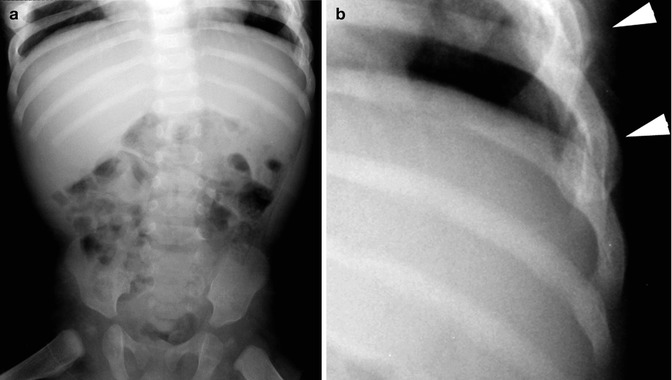

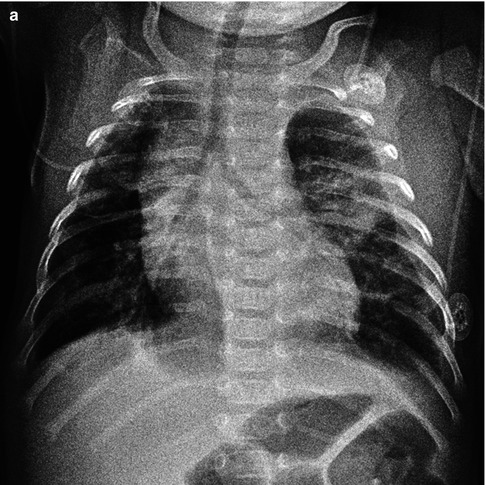

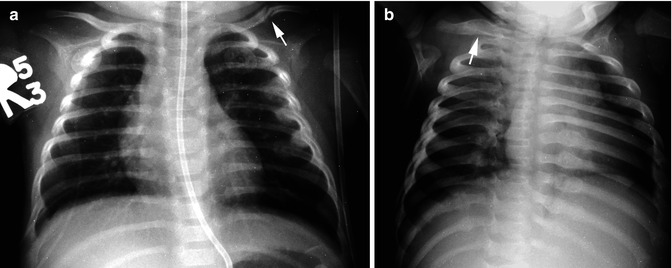

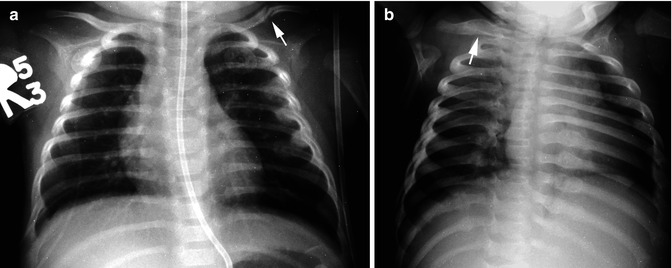

The presentation of a battered child or a child/infant subject to non-accidental trauma is common in the emergency room setting. Very often the patient presents with a bizarre history, no history, or a suspicious history. Usually a detailed history is the true history, while a nebulous, changing, or not making sense history is suspicious. In addition, in many cases, the imaging findings are obscure or just at the edge of the film because the film was not obtained for the prime purpose of looking for fractures. For example, in the infant illustrated in Fig. 12.1, the presenting problem was that of something wrong in the abdomen. The parents claimed that every time they tried to pick up the infant, the infant cried and the abdomen seemed to be a little distended. That is all there was to the history. Because of this, a single supine view of the abdomen was obtained (Fig. 12.1). When the image was inspected, the abdomen appeared normal. There was no evidence of visceromegaly, bowel obstruction, free air, or any other intraabdominal problem. However, with closer inspection, healing rib fracture were seen in the lower ribs (Fig.12.1a, b). This case not only emphasizes that one needs to look at the corners of the films but also that one needs to look at the ribs. We have had a rule for a long time, and the rule goes as follows “if you are dealing with a potential battered child or you are dealing with an infant/young child where things do not seem to be fitting, take a second look at the ribs.” It is very difficult for an infant/young child to sustain rib fractures from ordinary activity [1–4]. When present, they are a very strong signal that non-accidental trauma is at play.

Fig. 12.1

(a) KUB in patient who was irritable and cranky. The abdominal findings are normal, but there is evidence of healing rib fractures bilaterally, just at the top edges of the image. (b) Magnified view of the left ribs demonstrates healing rib fractures (arrowheads)

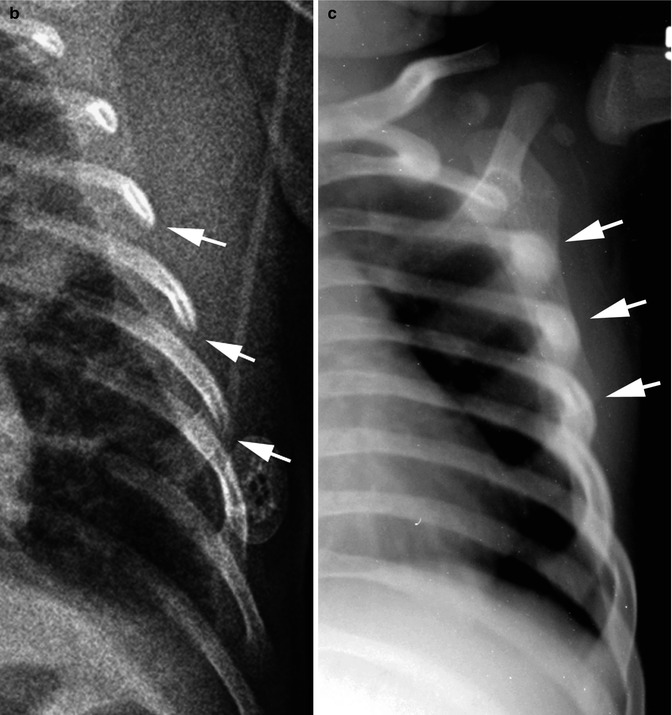

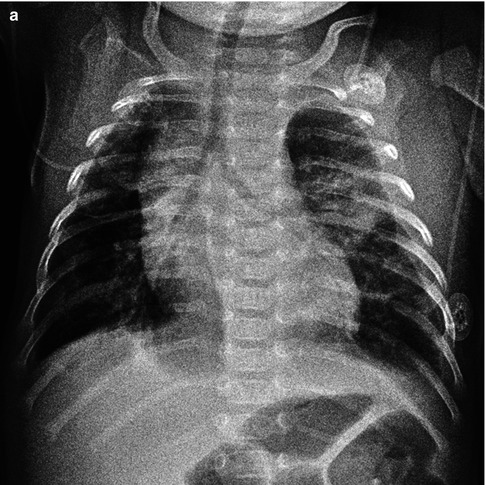

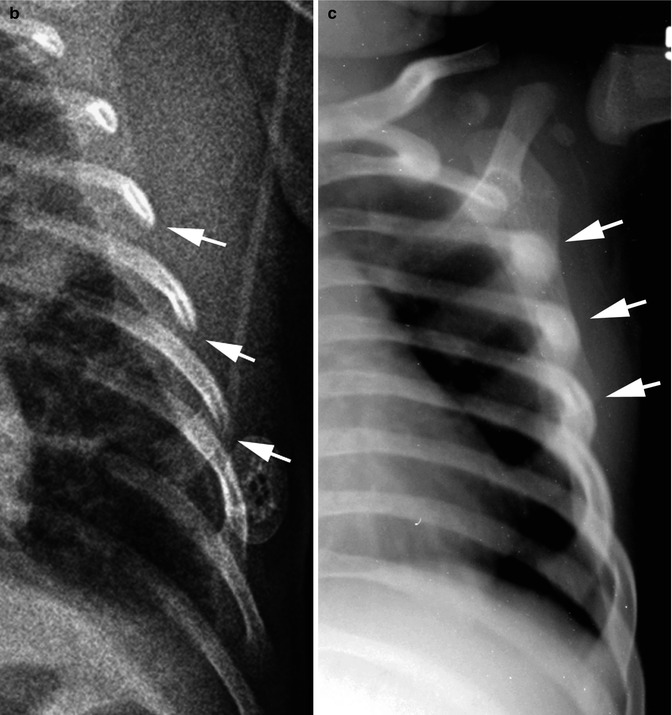

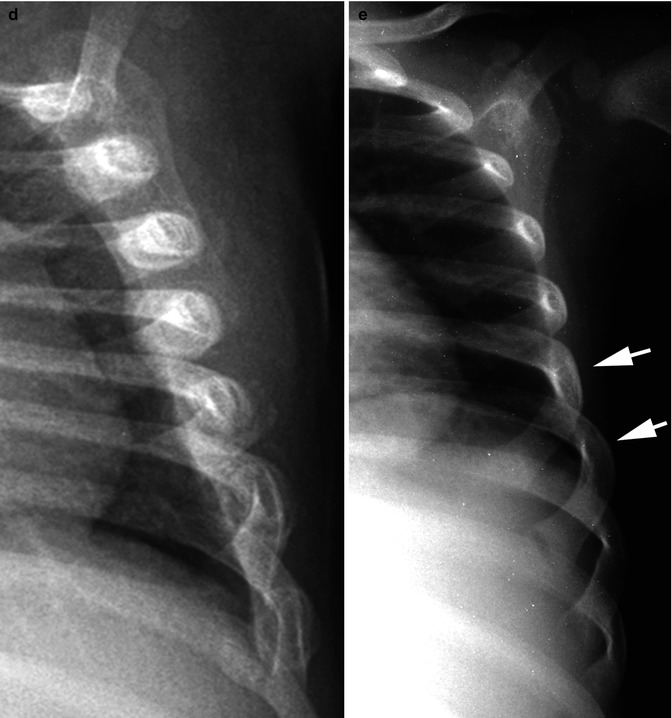

Fresh rib fractures, unless some angulation of the ribs occurs, may be difficult to detect. Angulated fractures are more readily detected (Fig. 12.2a, b), and all of these rib fractures may require oblique views of the chest for full evaluation and detection. Thereafter, as the fractures heal, callus formation is deposited around the fracture, and eventually the fracture has a round “ball-like” appearance (Fig. 12.2c, d). This appearance places the fracture somewhere between 2 and 4 weeks of age. Thereafter the callus smooths out, and only a thick rib is identified (Fig. 12.2e). All in all, from fresh fracture to thick rib requires about 10 weeks [3].

Fig. 12.2

Rib fractures: healing sequence, various patients. (a) In this patient, acute angled rib fractures are seen on the left. There also is some pleural thickening. All of this suggests acute injury. (b) Close-up demonstrates the angled rib fractures (arrows). (c) Healing phase, approximately 2 weeks. Note early callus formation around the healing rib fractures (arrows). (d) Healing approximately 4 weeks. Note the abundant target-like callus formation around the ribs. (e) Ten plus weeks out, only residual thickening of the ribs is seen (arrows)

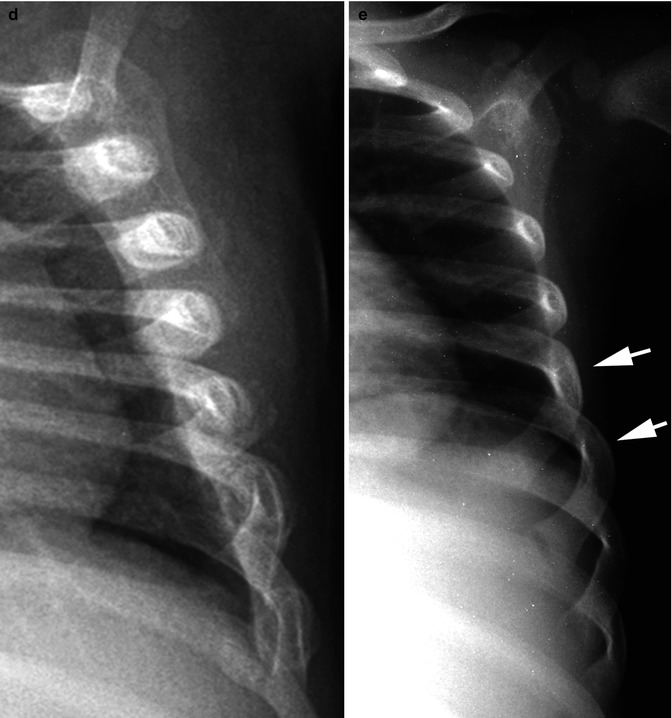

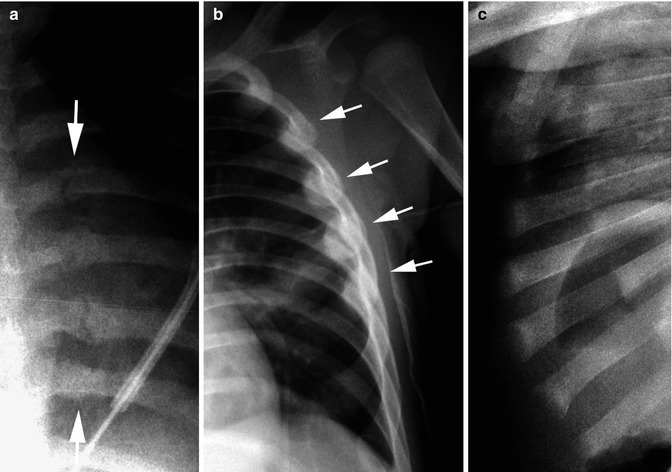

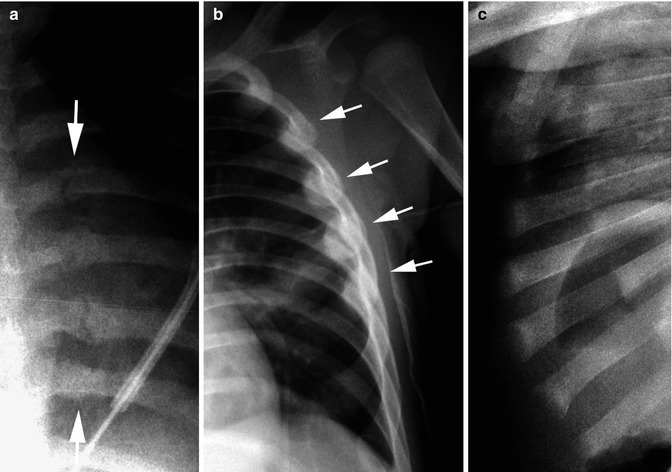

Rib fractures have different mechanics at play in terms of whether they are posterior, mid, or anterior fractures [1–4]. With posterior fractures, shaking leverage against the transverse process causes the proximal rib to fracture [2]. These fractures may be difficult to detect on initial films but usually are apparent with healing (Fig. 12.3a). Fractures through the midportion of the ribs occur from squeezing and shaking and are the easiest to detect (Fig. 12.3b). With anterior rib fractures, costochondral separations occur from shaking (mainly) and squeezing. Initially very little if anything abnormal is seen, but eventually there is increased cupping and density of the anterior ribs (Fig. 12.3c). Of the three fractures, the anterior rib fractures are the most difficult to detect [4], and they are usually easier to detect on lateral chest films.

Fig. 12.3

Rib fractures: location. (a) Posterior rib fractures healing. There are four fractures between the arrows. (b) Lateral rib fractures healing (arrows). (c) Anterior rib fractures. Costochondral fractures manifest by increased cupping and sclerosis of the anterior ribs

Next to the ribs, always look at the clavicles [3]. The reason for this is that when an infant is shaken, the hands and fingers go around the thorax and squeeze the thorax and ribs, but the thumbs are anchored over the anterior chest with their tips usually lying over the clavicles. Therefore, not only do the ribs suffer from squeezing and shaking but so do the clavicles (Fig. 12.4). The healing sequence of clavicular fractures is the same as with rib fractures, and therefore, from fracture to only a thick clavicle is about a 10-week time period.

Fig. 12.4

Clavicle fractures. (a) Note the fresh midshaft left clavicular fracture (arrow). Also note subtle evidence of healing lateral rib fractures on the left, ribs two to five. (b) Healed clavicular fracture (arrow). Note the healed posterior rib fractures on the left and the right

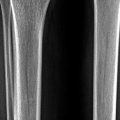

Metaphyseal corner fractures are characteristic of the “shaken baby syndrome” [5, 6]. These fractures are basically Salter–Harris I or II fractures which occur over a 360° radius around the involved metaphysis. In other words, with shaking, there is back and forth, side to side, and rotation of the extremities around the involved joint. Because of this, a ring of bone is avulsed from the metaphysis. This ring of bone may be seen as an acute avulsion (Fig. 12.5d) but is more clearly visible with healing (Fig. 12.5a–c). The lesion has been referred to as the classic metaphyseal lesion (CML) [6], and although the fracture is classic for the battered child syndrome, it can be seen under other circumstances [7, 8] including premature infants who suffer from metabolic bone diseases of the premature, rickets, neurogenic patients, and patients with physiologic bowing of the lower extremity. In all of these cases, one usually can appreciate that the underlying predisposing problem is not simple non-accidental trauma for the bones will be osteopenic (Fig. 12.5). In this regard, rickets as a condition misinterpreted for the battered child has basically been set aside [9, 10], and this also been our experience. In this regard, basically when one encounters the classic metaphyseal lesion in patients with other diseases, the patients have the severe/congenital forms of the diseases, and there will be no difficulty detecting that this predisposing condition exists. These typical corner fractures tend not to occur in the milder forms of these conditions.

Fig. 12.5

Classic metaphyseal lesion (CML). (a) Typical healing epiphyseal–metaphyseal fracture with fragmentation irregularity and periosteal new-bone formation. (b) More advance healing leaves only residual beaking. (c) Healing of a minimal epiphyseal fracture. Note the irregular lucent metaphyseal edge. (d) Minimal ring epiphyseal–metaphyseal fracture (arrow)

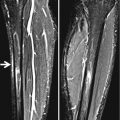

Another time when the metaphyseal corner fracture can be present and be normal is in infants with physiologic bowing of the legs. Physiologic bowing is very common under 2–3 years of age and is associated with sturdy muscles. What happens is that there is pulling and stress on the medial metaphysis of the femur and often the tibia, and breaking along with corner fractures can occur (Fig. 12.6). This phenomenon occurs medially and not laterally, and therefore, if one sees beaking laterally, even in a patient with bowed legs, one should become suspicious. In addition, in patients with bowed legs, the bones are very well mineralized.