18 Benign and Malignant (Cystic) Tumors of the Pancreas Various types of benign and malignant cystic tumor can occur in the pancreas. Cystic lesions in the pancreas can be divided pathologically into retention cysts, pseudocysts, and cystic neoplasms. Distinguishing between the various types of lesion has important prognostic and therapeutic implications. Cystic lesions of the pancreas are associated with systemic disease (e.g., cystic fibrosis and von Hippel-Lindau disease). In the latter, the reported incidence is ≈ 10–20%. In a recent study, 77% of 158 consecutive patients had lesions in the pancreas, including cysts, serous cystadenomas, and neuroendocrine tumors. Most patients had no symptoms related to peptide hormone secretion. As a result, many of these lesions are diagnosed incidentally in surveillance examinations—for example, for renal tumors. Anatomic or intensive biochemical studies reveal pancreatic tumors in up to 80% of patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of pancreatic tumors is summarized in Table 18.1. Simple cysts. Simple (true or retention) cysts of the pancreas are often small, fluid-containing spaces lined with normal duct and centroacinar cells. They are usually incidental findings with no clinical significance and can be left untreated. They are found in about 25% of patients with cystic fibrosis.1 In sharp contrast to other parenchymal organs (kidney, liver), simple cysts in the pancreas are a very rare finding. Other uncommon benign cysts of the pancreas are benign mucinous cysts and lymphoepithelial cysts. Pseudocysts. Pancreatic pseudocysts develop as a result of pancreatic inflammation and necrosis. Most pseudocysts communicate with the pancreatic ductal system and contain high concentrations of enzymes. The walls of pseudocysts are formed by adjacent structures and consist of fibrous and granulation tissue and are therefore not lined with normal duct and centroacinar cells. The lack of an epithelial lining thus distinguishes pseudocysts from true cystic lesions of the pancreas. A pseudocyst should be suspected in patients with a recent history of pancreatitis and an elevated serum amylase concentration, when the lesion contains enzyme-rich watery fluid and communicates with the pancreatic duct as assessed by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). The diagnostic implications of pancreatic pseudocysts are described in the respective sections below. When a diagnosis of pseudocyst is made, the management is mostly determined by the symptoms. Asymptomatic pseudocysts that are not increasing in size can be monitored, even if they are large. Symptoms should be treated either with resection (for lesions in the body or tail of the pancreas) or drainage (for lesions anywhere in the pancreas). Drainage can be carried out with endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) guidance, either into the stomach or (less favorably) into the duodenum or via the percutaneous route.2–10 Pseudocysts can also be drained surgically by anastomosing the stomach, duodenum, or jejunum to the cyst wall. The therapeutic implications mainly depend on the locally available expertise and clinicians’ preferences, since none of the methods has been shown to be superior to the others. EUS management is discussed in Chapter 19. EUS in acute pancreatitis (Fig. 18.1) is performed routinely to demonstrate the biliary etiology, but has rarely been used to assess the degree of necrosis.

Benign |

Serous cystadenoma |

Mucinous cystadenoma |

Intraductal papillary mucinous adenoma |

Mature teratoma |

Borderline |

Mucinous cystic tumor with moderate dysplasia |

Intraductal mucinous papillary tumor with moderate dysplasia |

Solid pseudopapillary tumor |

Malignant |

Highly ductal dysplasia, carcinoma in situ |

Ductal adenocarcinoma |

Serous cystadenocarcinoma |

Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma |

Intraductal papillary mucinous carcinoma |

Acinar cell carcinoma |

Solid pseudopapillary carcinoma |

Pancreatic blastoma |

Osteoclasts similar to giant cell tumor |

Mixed carcinoma |

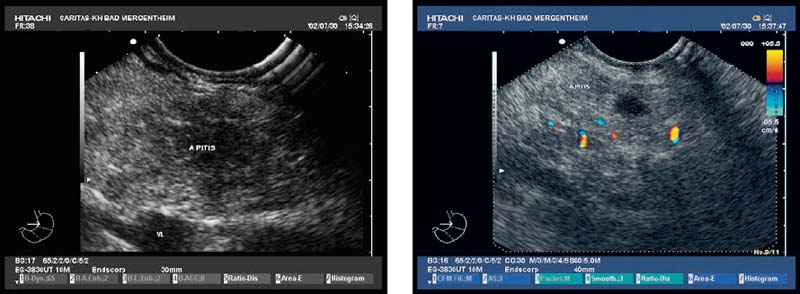

Fig. 18.1a, b Acute pancreatitis. Exudates and necrosis can be delineated with high-resolution EUS, using color Doppler imaging.

More than 25 different types of cystic pancreatic neoplasm have now been described, most of which are very rare. Four of these types account for at least two-thirds of all cystic neoplasms in the pancreas:

• Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN)

• Serous cystic neoplasm (SCN; microcystic serous cystadenoma; oligocystic/macrocystic cystadenoma)

• Mucinous cystic neoplasm (MCN; cystadenoma/cystadenocarcinoma)

• Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm (SPN; also known as papillary cystic neoplasm, solid pseudopapillary tumor, or Frantz-Gruber tumor)11,12

Epidemiology. Older statistics showed that mucinous cystadenoma is the most common type of cystic pancreatic neoplasm and that serous cystadenoma is the second most common. Papillary cystic neoplasm (or tumor, also known as solid pseudopapillary neoplasm or tumor) is the least common type of pancreatic cystic neoplasm.13,14 However, recent data show that IPMN is by far the most common cystic neoplasm in the pancreas, accounting for around one-third of cystic neoplasms. Cystic lesions of the pancreas, even when found incidentally, may have a malignant potential and require diagnostic evaluation regardless of their size.11,12

Diagnosis. The EUS findings by themselves are not accurate enough to diagnose the type of cystic lesion of the pancreas definitively, or to determine its malignant potential in all cases. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) with assessment of lipase and tumor markers may increase the accuracy (see Chapters 16 and 17).15–18

Cytology. Cytological analysis of the cyst fluid obtained using EUS-FNA lacks sensitivity, but has a high level of specificity for malignancies and mucinous cystic neoplasms. Measurement of cyst fluid amylase, lipase, and various tumor markers such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and CA19–9 is clinically useful. One study examined 341 patients who underwent EUS-FNA of pancreatic cystic lesions. Cyst fluid was analyzed for CEA, CA72–4, CA125, CA19–9, and CA15–3. A histological diagnosis was obtained in 112 patients who underwent surgical resection (68 with mucinous lesions, seven with serous, 27 with inflammatory, five with endocrine, and five with other types of cystic lesion). Using a cut-off value of 192ng/mL, CEA levels were the most accurate method of differentiating between mucinous and nonmucinous cystic lesions (sensitivity 73%, specificity 84%). There was no combination of tests that provided greater accuracy than CEA alone.19 In addition, biopsies may not be diagnostic, since such samples frequently do not contain cells that are representative of the entire cyst lining. The relatively low sensitivity and specificity levels raise questions about the reliability of these methods for assessing the need for surgery in individual patients.

Histology. Cytological examination of the cystic fluid may allow diagnosis if either glycogen-rich cells (suggesting serous cystadenoma) or mucin-containing cells (suggesting mucinous lesions) are present. However, false-negative cytology is not unusual, and mucus-secreting cells can be found in the normal pancreatic duct lining. In patients with suspected serous cystadenoma, a core biopsy for histology is required if the lesion appears solid, to avoid surgery (see Chapter 17).

Immunohistochemistry and molecular genetics. The accuracy of ultrasound-guided and EUS-guided biopsy can be enhanced using immunohistochemical tests (mucin expression profile) and molecular genetic tests (K-ras, loss of heterozygosity; see Chapter 17).

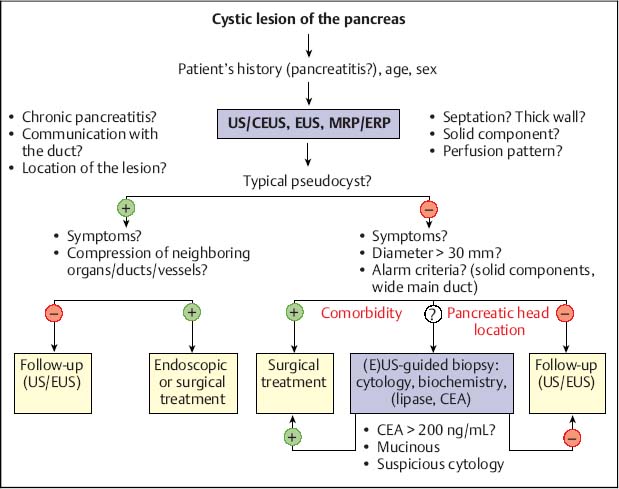

Fig. 18.2 Management of cystic pancreatic lesions. CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CEUS, contrast-enhanced ultrasound; ERP, endoscopic retrograde pancreatography; EUS, endoscopic ultrasonography; MRP, magnetic resonance pancreatography; US, ultrasound.

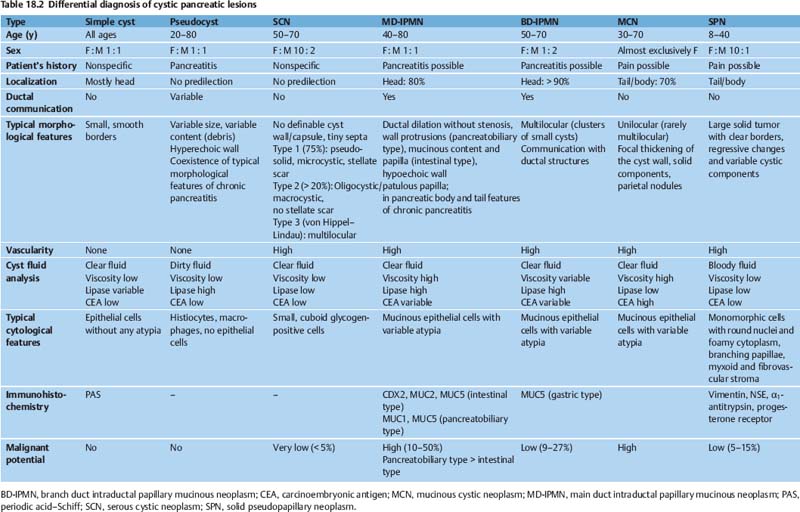

The differential diagnosis of cystic pancreatic lesions is challenging. Diagnosis should be based on a combination of the patient’s history, clinical data, endosonographic morphology, cytomorphological features, and biochemical analysis of cyst fluid. Taking a comprehensive view—including the patient’s clinical data (sex, age, race, history of pancreatitis), morphological features on EUS and radiological studies (size, location, pancreatic duct dilation, wall thickness, ductal communication, mural protuberances, and solid components) and the results of EUS-guided biopsy (cytology, fluid markers)—is the key to achieving accurate differential diagnosis of cystic pancreatic lesions (Table 18.2) and for predicting their malignant potential (Table 18.3).17,18

Safety. FNA of cystic lesions is generally safe. Prophylactic antibiotics should be administered to patients undergoing EUS-FNA, ERCP, or endoscopic drainage procedures for (inflammatory) cystic lesions of the pancreas.

Differential diagnosis (Table 18.2). It is sometimes difficult to distinguish between pseudocysts and serous and mucinous tumors, as the latter may contain enzyme-rich fluid, communicate with the ductal system, and may be seen in patients with symptoms of recent pancreatitis.

Endoscopic ultrasound may make it possible to distinguish between serous and mucinous neoplasms by revealing a mass composed of either many tiny cysts (microcystic), showing a solid-appearing hypervascular tumor, or showing several large cysts (macrocystic). Serous cystadenomas typically have a central scar and central vessel, similar to focal nodular hyperplasia in the liver. This finding can often also be seen with transabdominal ultrasonography. However, even with these findings, it is not possible to exclude the presence of a malignancy, especially a neuroendocrine tumor.20

Therapy. The EUS findings by themselves are not sufficiently accurate to diagnose the type of cystic lesion of the pancreas definitively or to determine its malignant potential in all cases, and surgery is therefore mandatory, depending on the patient’s age and comorbidity. In patients with histologically confirmed serous cystadenomas, which are only accessible via the transabdominal route or using EUS-guided Tru-Cut biopsy,21 careful follow-up may be possible. (Fig. 18.2)22,23

The management of patients with uncertain cystic lesions is difficult. In a study including 398 patients with cystadenomas from 73 institutions, 372 of whom underwent surgery, accurate preoperative diagnosis of the tumor type was achieved in only 20% of those who were ultimately diagnosed with serous cystadenomas, 30% of those with mucinous cystadenomas, and 29% of those with mucinous cystadenocarcinomas.24 Many experts and pancreatic surgeons therefore recommend resection for even moderately suspicious lesions in the body and tail of the pancreas, and for highly suspicious lesions in the head of the gland.

There are currently no established endoscopic treatments for cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. EUS and ERCP should always be considered before surgical or percutaneous drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts, in order to optimize patient selection. In one prospective randomized study, EUS-guided ethanol lavage of unilocular cystic lesions of the pancreas was compared with saline solution lavage. EUS-guided ethanol lavage resulted in a greater reduction in the cyst size, but only led to complete disappearance of the cysts in one-third of the patients.25

EUS criteria |

Wall ≥ 3 mm or thick septa |

Macroseptation (cystic components >10 mm) |

Solid parts or solid-cystic tumor |

Focal thickening of the wall, mass extending beyond the duct wall |

Wall protrusions |

Cystic dilation of the main pancreatic duct > 10 mm |

Lesion >30 mm |

Growth during follow-up |

EUS-FNA criteria |

High viscosity of the cyst fluid |

High CEA level in the cyst fluid (variable cut-off values) |

Presence of mucin in the cyst fluid (MUC1, MUC2 and MUC5AC) |

Cytological or histological detection of mucinous epithelium |

Cytological detection of nuclear atypia, necrosis, and significant background inflammation |

Cytological or histological diagnosis of defined cystic neoplasia with malignant potential |

K-ras mutation and loss of heterozygosity |

High telomerase activity in cyst fluid |

Mucinous Cystadenoma and Cystadenocarcinoma

Mucinous Cystadenoma and Cystadenocarcinoma

Mucinous cystadenomas consist of one or more macrocystic spaces lined with mucus-secreting cells and are typically located in the body or tail of the pancreas. It is often difficult to make the diagnosis on the basis of biopsy or aspiration samples, as the cellular lining is frequently irregular. A mucinous lesion should be suspected when one or more macrocystic spaces containing mucin are found. Most of these mucinous tumors are malignant at time of diagnosis, and benign forms have a high potential for malignant transformation (Figs. 18.3 and 18.4). During ERCP, tissue sampling with brushing, and/or biopsy, and/or pancreatic fluid collection, should be performed whenever possible.

When the diagnosis of a mucinous cystadenoma is made, the lesion should be resected, due to the high potential for malignant change, but also depending on the patient’s age and comorbidity. Distal pancreatectomy should be carried out for lesions in the tail or body of the pancreas, and patients with lesions in the pancreatic head should undergo pancreaticoduodenectomy.

Another type of mucinous tumor of the pancreas is intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) or mucinous duct ectasia. The relationship between IPMNs (in which an increasing incidence is being observed) and mucinous cystadenoma/cystadenocarcinomas is not yet clear.20

Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm

Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm

IPMNs were first described in 1982 in patients suspected of having pancreatic carcinoma who had a favorable outcome. A variety of confusing synonyms have been used—for example, mucinous ductal ectasia, mucin-producing carcinoma, intraductal mucin-producing tumor, intraductal papillary hyperplasia, intraductal papillary tumor, intraductal papillary neoplasm, etc. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms show dilated ductal segments lined with mucus-secreting cells and may be located within the head of the pancreas or diffusely throughout the organ. IPMNs have been subclassified into a main duct type (MD-IPMN) and a branch duct type (BD-IPMN, often in the uncinate process) based on the anatomical involvement of the pancreatic duct. The malignant potential of MD-IPMNs is nearly as high as that of mucinous cystic neoplasms. The BD-IPMN subtype is associated with less aggressive histological features in comparison with the MD-IPMN subtype. Four subtypes of IPMN are currently distinguished: the intestinal type (common), a pancreatobiliary type (uncommon), and an oncocytic type (very rare) may be found in patients with MD-IPMN. The gastric type, which is the most common, corresponds to the BD-IPMN. These four types have special biological properties, which have prognostic implications. The majority of patients with IPMNs do not have invasive cancer at the time of diagnosis, and the rate of progression appears to be slow (more than 5 years).26–28

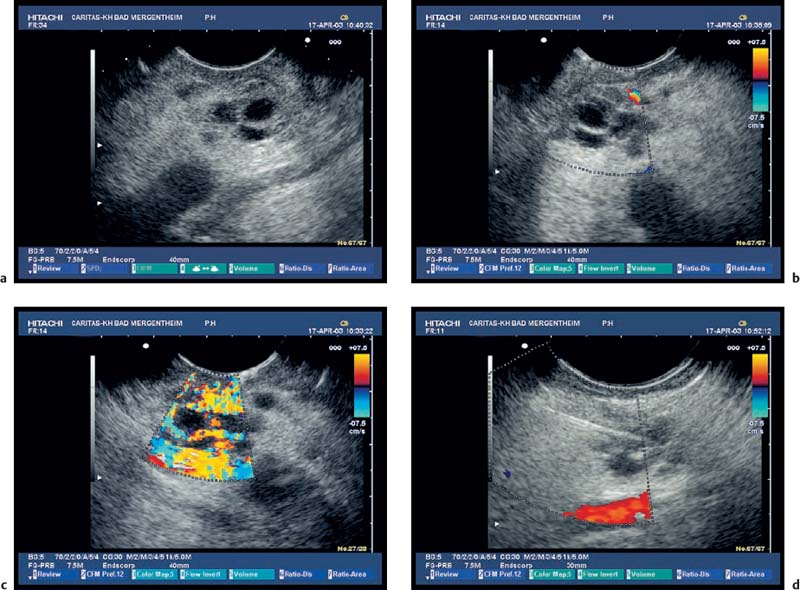

Fig. 18.3a–d Image of a partly solid and partly cystic mass, which was identified as a pseudocyst with an external transabdominal examination.

a B-mode.

b Color duplex ultrasonography.

c Vascularization of the tumor areas is identified after application of the echo contrast agent SonoVue.

d The tumor areas were aspirated in the same procedure. The cytological and histological diagnosis confirmed that the lesion was a mucinous cystadenoma, with no signs of malignancy.

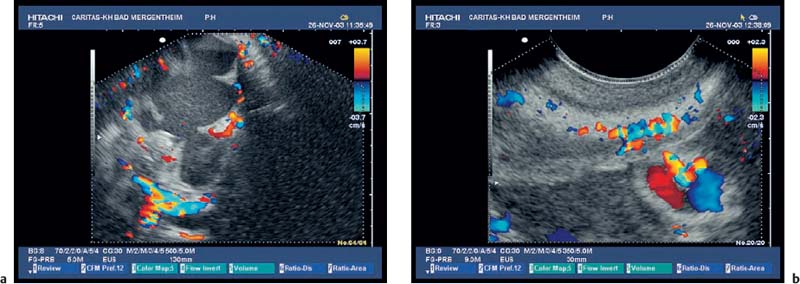

Fig. 18.4a–d Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma of the pancreas with mucus-containingcysts (a) and vascularized septa (b) and collateralsdueto portal vein thrombosis (c, d).

Epidemiology. IPMNs have most commonly been described in men over the age of 60, some of whom have symptoms suggestive of chronic obstructive pancreatitis or acute recurrent pancreatitis due to intermittent obstruction of the pancreatic duct with mucus plugs. The etiology of IPMN is unclear. It has been described in association with familial adenomatous polyposis, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, and other nonpancreatic tumors.

Diagnosis. There are three classic signs of MD-IPMN: a segmental or diffusely dilated main pancreatic duct without involvement of the common bile duct; a patulous ampullary orifice (“fishmouth”), frequently with mucus secretion (specific but not sensitive); and mural nodules. BD-IPMN is associated with multiple small cysts (5–20 mm) communicating with branch ducts. Dilation of the pancreatic duct to over 10 mm and cysts larger than 20 mm are suggestive of malignancy. Intraductal ultrasonography can be helpful for assessing the tumor extent in MD-IPMNs, but is rarely performed. EUS-FNA of the dilated pancreatic duct, including mural nodules and especially solid components of the tumor, may be helpful in the diagnosis (Figs. 18.5 and 18.6). Histopathological analysis tends to underestimate the tumor grade.29

Tumor markers are elevated in fewer than 25% of patients and are not helpful indicators of malignant transformation. Pancreatic secretions can be tested for molecular markers such as K-ras, P53, and telomerase activity, but the results have so far been inconsistent.

Differential diagnosis. The differential diagnosis of IPMN includes chronic obstructive pancreatitis, mucinous cystic tumors of the pancreas, and rarely pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.

Therapy. When an MD-IPMN is diagnosed, the lesion should be resected, due to the high potential for malignant change, but also depending on the patient’s age and comorbidity and the type of lesion involved. BD-IPMNs less than 30 mm in diameter with a thin wall, without papillary wall protrusions, without thick septumlike structures, and without dilation of the main pancreatic duct progress very slowly. In view of the risks of pancreatic surgery, close monitoring—for example, with periodical EUS examinations—may be justified in patients with these lesions.1726,30

Patients with recurrent pancreatitis caused by IPMN-induced intermittent obstruction should undergo resection of the mucous-secreting abnormal portion of the pancreas. Distal pancreatectomy, pancreaticoduodenectomy, or even total pancreatectomy, depending on the location and extent of the lesion, may be necessary. In our experience, patients with recurrent pancreatitis who are not suitable for surgery may benefit from endoscopic therapy.

Microcystic pancreatic adenomas were formerly considered a rarity. Nowadays, with technological advances in the equipment, localized changes in the pancreas are much more frequently observed. In contrast to mucous cystadenomas and IPMNs, serous cystadenomas have a very low potential for malignant transformation. Tumors are distributed throughout the pancreas without predilection (Fig. 18.7). Histologically, the lesions typically consist of multiple small cysts lined with glycogen-rich cells, with a regular vascular architecture.

It has been found useful to remove larger cylinders of tissue, as the specimens obtained with EUS-FNA are only sufficient for determining malignancy, but not for classifying the tumor type. In patients with suspected serous cystadenomas, core biopsies for histology are therefore required if the lesion appears solid, in order to avoid surgery. The results of a recent pilot study suggested that EUS-guided Tru-Cut biopsy (EUS-TCB) is capable of collecting sufficient tissue in cases of serous cystadenoma.21 In a patient with a definitive diagnosis of a serous cystadenoma, the management is determined by age, comorbidity, symptoms, progression, and lesion location. Symptomatic or enlarging serous cystadenomas in healthy young patients should be resected. Lesions in the body or tail of the pancreas require distal pancreatectomy, while those in the head of the gland are enucleated or resected with pancreaticoduodenectomy. Small, asymptomatic, and nonenlarging serous cystadenomas can be monitored, as the risk of malignant change is very low. The optimal interval for repeating imaging examinations in such patients is not known, but should be not longer than 12 months.

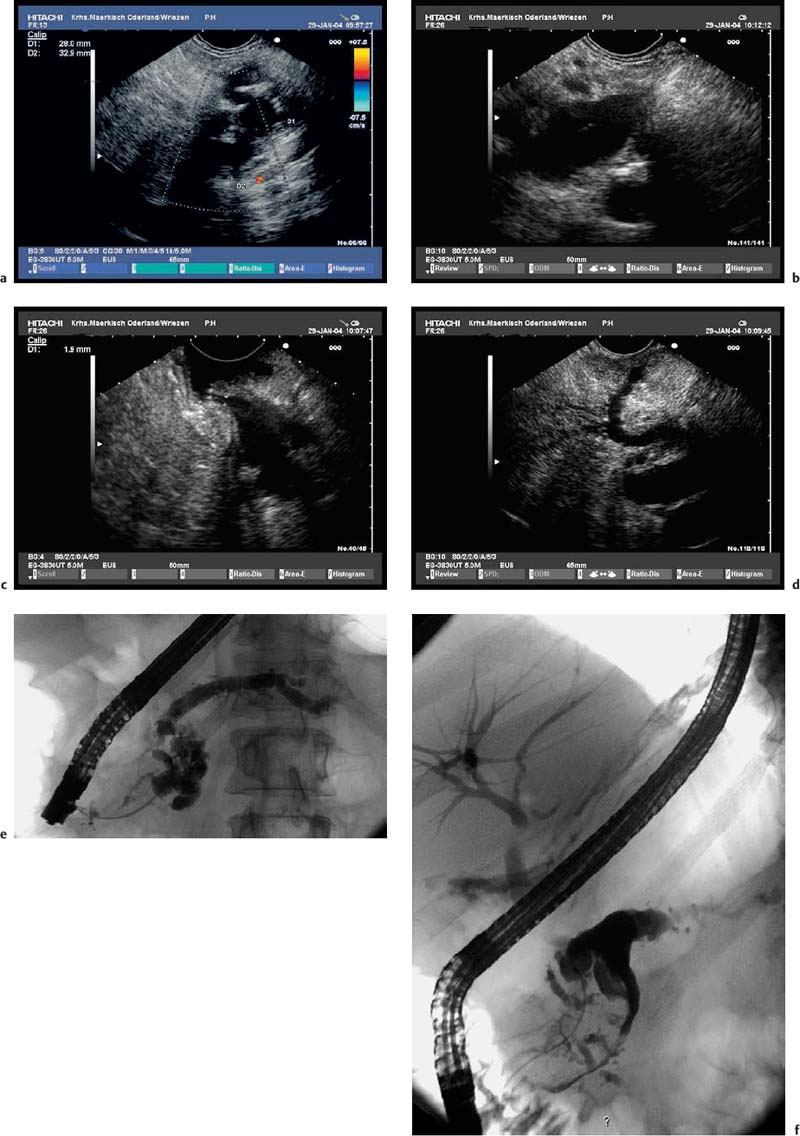

Fig. 18.5a–f Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs) of the pancreas (main duct type).

a Tortuous dilation of the main pancreatic duct in the pancreatic neck.

b Cystic spaces with incompletely anechoic luminal contents in the pancreatic body.

c The orifice of the main pancreatic duct is wide open.

d There is also dilation of the accessory pancreatic duct, viewed from the minor papilla.

e, f The corresponding endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) images show tortuous dilation and cystic cavities in the pancreatic head and neck, as well as dilation of the main pancreatic ductin the body and tail of the pancreas: opacification from the major (e) and from the minor (f) papilla.

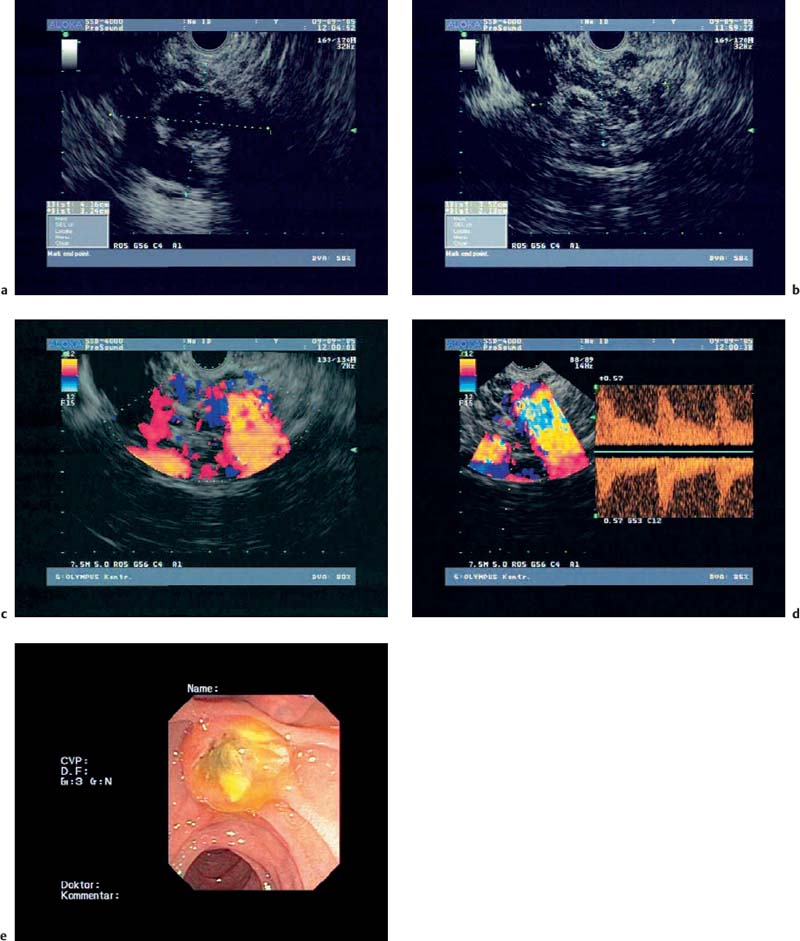

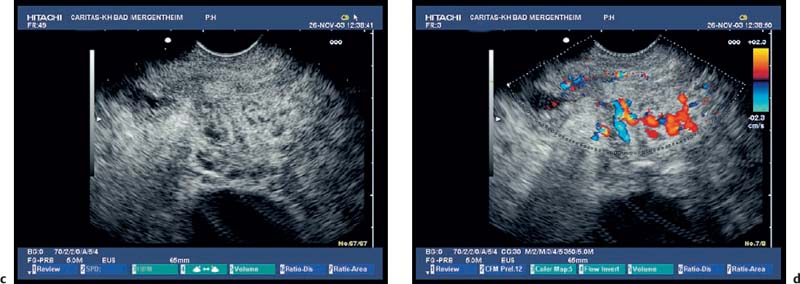

Fig. 18.6a–e Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs) of the pancreas (courtesy of M. Hocke, Meiningen, Germany).

a, b B-mode.

c Color Doppler imaging.

d Spectral analysis.

e Endoscopic image.

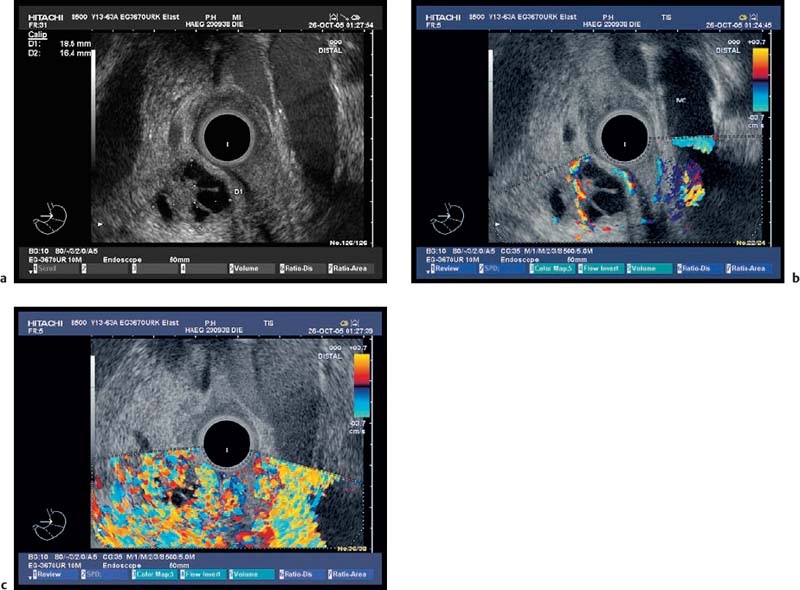

Fig. 18.7a–c

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Serous Cystadenoma

Serous Cystadenoma