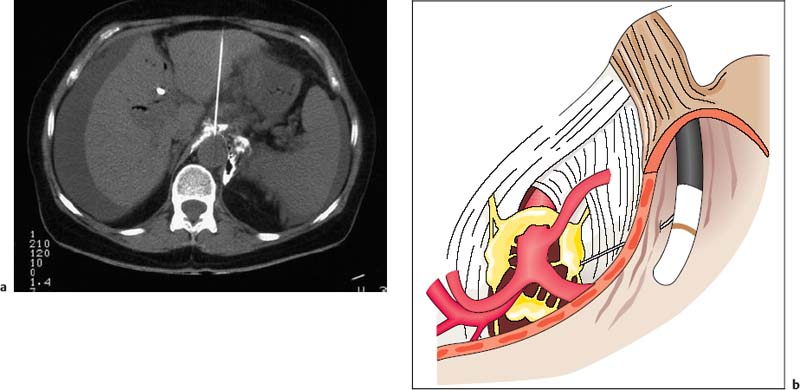

30 EUS-Guided Neurolysis of the Celiac Plexus Celiac plexus neurolysis has been used since 1950 to treat severe visceral pain syndromes. In the initial clinical studies, dorsal and paraspinal routes or transabdominal techniques with fluoroscopic guidance were used to access the region of the celiac trunk. These techniques were mainly used in large treatment centers to treat intractable pain caused by pancreatic carcinoma, and sometimes in chronic pancreatitis. However, because of the high level of expertise and specialization required to carry out such invasive procedures safely in patients, the techniques did not come into widespread use outside a few tertiary care centers. Alternative surgical methods also never became treatment options, as they were even more invasive and were not an attractive option for use in terminally ill groups of patients. With the advent of various highly effective and potent analgesic drugs and anesthetics, interest in developing additional invasive methods of treating cancer pain declined even further. However, when computed tomography (CT) techniques were further refined during the 1980s, interest among clinicians gradually returned to the issue of celiac plexus neurolysis (Fig. 30.1a). Since then, a few specialized pain centers have reported clinical “success rates” in the range of 60–85% with CT-guided interventions in uncontrolled open studies, although evidence from controlled studies is still lacking. A significant risk of a few but serious side effects and complications associated with percutaneous plexus block interventions, including paraplegia and pneumothorax, was encountered with CT-guided techniques, which is one of the major reasons for continuing efforts since the mid-1990s to develop novel techniques such as endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided plexus neurolysis (EUS-CPN). This approach always appeared attractive, as it has the advantages that it is carried out with the patient in intravenous sedation and is considerably less invasive, since very fine needles are used (22–25 G) with direct ultrasound visualization, very close to the anatomical structures that indicate the location of the celiac plexus—the neural ganglionic structures of which are not visible themselves with any imaging methods (Fig. 30.1b). Fig. 30.1a, b a Computed tomography-guided celiac plexus neurolysis. b Endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus blockade, showing some of the anatomical landmarks. However, the clinical effectiveness of this novel interventional EUS technique has still not yet been confirmed in randomized and controlled clinical studies. The initial studies and uncontrolled clinical studies currently in progress1–4 have provided encouraging results with regard to the feasibility and safety of EUS-CPN in this setting. Technical success was reported in 50–90% of cases, with reduced analgesic requirements and stabilization of the pain. The clinical effectiveness may be greater when alcohol is injected bilaterally than when injected centrally, relative to the supposed position of the celiac plexus under EUS vision.4 Relevant side effects of EUS-CPN include transient diarrhea, hypotension, and rare cases of infection and bleeding. No randomized controlled clinical studies have been published on the topic to date; an attempt was made in German centers, but failed to obtain ethics approval. Consequently, no sham-controlled, randomized studies are currently available that support a major role for this attractive technique as a standard procedure of care in clinical oncology. However, a recent “meta-analysis”5 of eight uncontrolled studies concluded that EUS-guided CPN is safe and offers additional benefit for pain relief in some patients with cancer, although its use in chronic pancreatitis cannot be generally recommended as yet.

Diagnosis and/or local staging |

Mediastinal lymphomas (bronchial carcinoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis) |

Mediastinal tumors (bronchial carcinoma, germ cell tumor, thymoma, metastases, inflammatory pseudotumors, etc.) |

Mediastinal abscess (perforating abscess, tuberculosis), fluid collections in the posterior mediastinum |

Pathological lesions in the thyroid and parathyroida |

N/M1A staging of esophageal carcinoma |

Intramural esophageal tumors |

Submucosal tumors in the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum |

Diagnosis of the type and N/M staging of tumors, metastases, lymph nodes, abscesses, and fluid collections in the peritoneum and retroperitoneum |

Diagnosis of periampullary tumors and malignant pancreatic tumors (including N and local M staging) |

Diagnosis of pathological lesions in the left lobe of the liver and central segments of the liver and hilar region (metastases, hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, adenoma, hilar lymph nodes, abscesses) |

Diagnosis of lesions in the left adrenal gland (metastases, adenomas, multiple endocrine neoplasia, tuberculosis) |

Circumscribed lesions of the spleen (non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Hodgkin disease, metastases) |

Therapy |

Celiac plexus block (neurolysis) for pain treatment in pancreatic and papillarycarcinoma, as well as chronic pancreatitis |

EUS-targeted drainage treatment for pancreatic pseudocysts (with stent placement) |

EUS-targeted drainage treatment in cholestasisa and accessible dilated bile ducts (with stent placement) |

EUS-guided endoscopic mucosal resection |

EUS-guided intratumoral fine-needle injection therapy |

a If these procedures are not easier with EUS-FNA, percutaneous access is also possible.

Minimally invasive interventional therapeutic endosonography has in the meantime emerged as an established technique. With the advent of improved endoscopic technology and the development of longitudinal scanners, it became possible some 20 years ago to combine ultrasonography and endoscopy in such a way that ultrasound-guided transmural needle interventions (biopsies) became possible during the same endoscopy session. This method has the unique advantage that even small and previously inaccessible pathological lesions (< 5 mm) can be reached with EUS guidance even if they are located in the posterior mediastinum, around the cardia, the cranial retroperitoneum, the adrenal glands, the hilum of the liver, the pancreatic region, and the rectum.6–10 These techniques were initially used only to obtain EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsies for diagnostic purposes, but today they are increasingly being used for transvisceral therapeutic procedures.1‘2,5‘11,12 The variety of options available and the fact that the complication rate is relatively low makes EUS-guided interventions particularly attractive. However, EUS-guided interventions are technically highly demanding, and considerable endoscopic and ultrasound training is needed to carry out procedures of this type safely. Skill and expertise in EUS-guided interventions are necessary before these rather delicate methods can be safely conducted in patients. Table 30.1 provides an overview of the current routine and experimental indications for diagnostic and therapeutic uses of EUS-FNA.

This chapter provides an overview of one of the earliest interventional applications of EUS-guided therapy: celiac plexus neurolysis (EUS-CPN) for the treatment of severe visceral pain in malignant disease, using injection therapy. It should be borne in mind that this form of treatment is largely supportive, although it can make a significant contribution to a comprehensive and interdisciplinary approach to pain management in malignant disease. It helps the clinician control pain in patients with end-stage disease and adds valuable nonpharmacological options. As mentioned, however, there is still a lack of prospective and controlled clinical studies.

Prerequisites for EUS-Guided Celiac Plexus Neurolysis and Other Treatments

The effectiveness of therapeutic EUS depends on a variety of different factors:

• General experience and skill. One of the most important prerequisites for carrying out EUS-guided treatments successfully is excellent endoscopic skills, with full mastery of all of the conventional endoscopic techniques using straight-viewing and side-viewing endoscopes, including esophagogastroduodenoscopy and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. In addition, comprehensive training in interventional transcutaneous sonography, including fine-needle puncture and drainage techniques, is needed in order to meet the high requirements for interventional therapeutic EUS.

• Specialized endosonography skills. Endoscopic ultrasonography with fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) is probably one of the most technically demanding and training-intensive endoscopic examination procedures. Experience with at least 250–300 previous endosonographic examinations, including fine-needle biopsies, is needed to ensure that treatments in this field are administered safely and successfully in routine clinical conditions in patients.

• Cost-effectiveness. Interventional EUS for routine use in an endoscopy department generally involves substantial costs, including the high initial investment and installation costs and expenses for repair procedures, as well as additional costs for accessory materials such as puncture needles and other appliances. These additional materials are usually much more expensive than any of the catheters and needles used for percutaneous procedures. Depending on the type of needle used and local price negotiations, the cost of a biopsy or injection needle as a single-use device can amount to € 150–300 (US$ 203–405). On top of this, costs for sedatives and anesthetics, cytology and/or histology, and microbiology have to be taken into account, representing an additional € 50–150 (US$ 68–203), depending on the severity and type of disease and procedure. With therapeutic interventions, even higher total costs have to be calculated (between approximately € 850 (US$1149) and € 1500 (US$2027) per drainage procedure) if metal stents are not inserted; metal stents can increase the cost up to a total of € 1500–2500 (US$2027–3379). Finally, the amount of time and the numbers of staff needed for demanding procedures such as these mean that the use of the techniques outside specialized care centers, with reasonable numbers of patients with special needs, is questionable and unattractive. In general, only specialized clinical care centers dealing with a significant number of complex gastroenterology and oncology cases, which also offer a wide range of minimally invasive visceral surgical procedures per year, should consider installing therapeutic EUS facilities in order to qualify as centers of expertise. Any other institutions would need to weigh up the benefits of such niche techniques carefully against the medical and financial risks, since basic endosonographic problems can be reasonably assessed with radial-scanning echoendoscopes, allowing appropriate selection of patients with special medical needs who can still be referred to secondary or tertiary care centers for therapeutic EUS.

Indications for Therapeutic EUS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree