Study

Year

Patients (n)

Age/gender

Treatment

Approach and location

Outcome

Pugh et al. [14]

1946

1

–

–

–

–

Sung et al. [7]

1987

2

–

Surgery

PA, below S3

Good, no LR

Hanakita et al. [15]

1988

1

42/F

Surgery, hemilaminectomy L4-S1

PA, L5-S1 lamina

Good, no LR

Gille et al. [16]

2004

1

45/F

Surgery, lumbotomy

PA, S1

Bess et al. [8]

2005

1

34/F

Surgery, MHE

PA, L5-S1 articular process

Good, no LR

Agrawal et al. [17]

2005

1

14/M

Surgery

PA, right ala sacrum

Good, no LR

Samartzis et al. [6]

2006

1

11/M

Surgery, en bloc excision with S1-S4 laminectomy

PA, S2 lamina

Good, no LR

Chin et al. [18]

2010

1

54/F

Surgery, en bloc excision

Abdominal-retroperitoneal approach, sacrum

Good, no LR

Kuraishi et a. [2]

2014

1

63/F

Surgery, hemilaminectomy right L5-S1

PA, S1 articular process

Good, no LR

Baruah et al. [19]

2015

1

21/M

Surgery, en bloc excision

PA, S3-S4 lamina

Good, no LR

Sciubba et al. [13]

2015

1

48/M

Surgery, en bloc excision

PA, S1

Good, no LR

1

48/M

Surgery, en bloc excision

PA, S1

LR

1

21/M

Surgery, en bloc excision

PA, S1

Good, no LR

1

17/M

Surgery, en bloc excision

PA, S1

Good, no LR

1

13/M

Surgery, en bloc excision

PA, L5-S3

Good, no LR

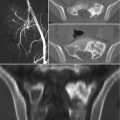

X-rays and computed tomography (CT) scans show the pathognomonic features of bone components with pedunculated or sessile base. However, plain X-rays are usually insufficient because of overlapping of other osseous structures [6, 15, 17]. MRI is important to visualize the size of the cartilaginous cap and the eventual neural structures compression. Differential diagnosis from other neoplasms involving the sacrum is not difficult. Parosteal chondrosarcomas are suspected if increasing size is noticed after skeletal maturity [1, 3, 12]. Malignant transformations to chondrosarcoma range between 10 and 20% in hereditary multiple exostosis and 1–5% in solitary osteochondromas [3, 12, 16]. When the cartilaginous cap is greater than 1–3 cm, in presence of new onset of symptoms or when the tumor rapidly increases in size, malignant changes should be suspected [13].

The mainstay of treatment is observation because most lesions are asymptomatic. En bloc surgical excision of sacral osteochondroma with free margins or marginal margins usually constitutes adequate treatment for symptomatic tumors although it is important to consider the risk of injuring nearby pelvic organs and neurovascular structures [23]. Tumors of the sacrum can be removed through anterior, posterior, or combined approaches [24]. The choice of the appropriate approach is dictated by the location of the tumor and the anatomic peculiarity and hypervascularity of the sacrum. Complete excision of the cartilaginous cap and its overlying periosteum is recommended to reduce the risk of local recurrence [3, 6, 25, 26]. Some authors suggest a frozen section biopsy to confirm margin free of tumor [19].

The outcome and prognosis after surgery of sacral osteochondromas are excellent. The risk of recurrence after treatment of osteochondroma of the spine or the sacrum is not well known because of the rare occurrence. Based on literature review, Gille et al. estimated 4% risk of recurrence in spine, slightly higher than the estimated 2% recurrence in long bones [16]. A tumor recurrence may represent a suspicious of malignancy [3, 12].

13.3 Chondroblastoma

Chondroblastoma is a rare benign cartilage-producing tumor consisting of about 1% of all bone tumors [3]. Chondroblastoma is usually found in the epiphyseal or epimetaphyseal areas of long bones, in males (male:female ratio 2:1), and could be found in any ages, even if it occurs most frequently between 10 and 25 years old. The incidence of vertebral chondroblastoma is 1.4% of all chondroblastomas, and less than five cases of sacral involvement have been reported in literature (only one clearly described) [27]. The radiological findings of vertebral chondroblastomas are nonspecific and biopsy should be performed considering possible more frequent differential diagnosis: aneurysmal bone cyst, giant cell tumor, chondromyxoid fibroma, osteoid osteoma, osteoblastoma, chondrosarcoma, chordoma, and metastasis [3]. Chondroblastomas of the spine behave more aggressively than those of long bones with a higher rate of local recurrence (about one-third of patients) [27–30]. Some authors suggested that this may be related to the frequent extension to adjacent soft tissue and the spinal canal, which precludes complete tumor resection [31, 32]. Three cases of tumor-related death have been reported due to direct invasion to adjacent soft-tissue and neurological structures [27, 30, 33]. Therefore, complete excision and long-term follow-up are generally recommended as the treatment modality for vertebral or sacral chondroblastomas.

13.4 Chondromyxoid Fibroma

Chondromyxoid fibroma (CMF) is a rare benign cartilaginous tumor generally observed between 5 and 30 years of age. It accounts for about 0.5% of all primary bone tumors [3, 34]. CMF of the sacrum is exceedingly rare, with less than ten cases reported in the literature (Table 13.2) [35–43]. Many of them demonstrate expansile or erosive imaging pattern, with cortical destruction, sclerotic and lobulated borders, septation, and intralesional calcifications [34]. Because of these radiographic similarities with more aggressive sacral pathology, differentiating CMF from chondrosarcoma, chordoma, and giant cell tumor on the basis of imaging alone is not possible [40]. CT-guided biopsy with histologic evaluation is mandatory for diagnosis. Although follow-up and detailed documentation are rather lacking in the treatment of sacral CMF, surgery in terms of total en bloc resection or intralesional curettage represents the current accepted management options. Radiation therapy has been used for sacral CMF in only one patient who died of complications before 4 months of follow-up [37]. The risk of local recurrence for CMF ranges between 4 and 80% [41], but higher risk can be expected in younger age group with spine lesions despite extensive curettage [36]. The longest reported follow-up for sacral CMF was a patient treated with curettage and bone grafting, who was found to be recurrencefree at 8-year follow-up [38]. Other authors reported no evidence of recurrence at about 1 year of follow-up after wide resection [40, 42].

Table 13.2

Chondromyxoid fibroma of the sacrum: review of the literature

Study | Year | Patients (n) | Age/gender | Treatment

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|

|---|