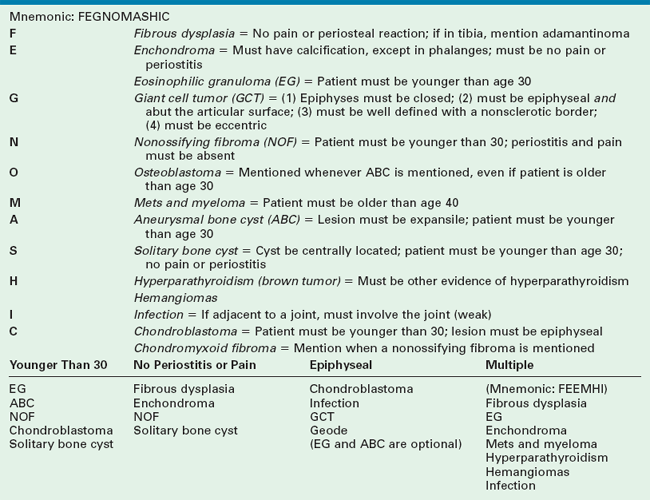

CHAPTER 2 FEGNOMASHIC is defined in Funk and Wagner’s unabridged dictionary, 13th edition, as “one who uses mnemonics.” It serves as a nice starting point for discussing possibilities that appear as benign lytic lesions in bone. That mnemonic has been in general use for many years, but I have never heard a claim as to who first coined it. The first mention of it that I saw in print was in 1972 in a radiology article by Gold, Ross, and Margulis.1 By itself it is merely a long list—about 14 entities—and needs to be coupled with other criteria so that it can be shortened into a manageable form for each particular case. For instance, if the lesion is epiphyseal, only three to five entities need to be mentioned, depending on how accurate you care to be. If multiple lesions are present, only half a dozen entities need to be discussed. Ways of narrowing the differential are discussed later in this chapter. I will give a brief description of each entity, because complete descriptions are readily available in any skeletal radiology text. What I will dwell on, however, are the points that are unique for each entity, thereby enabling differentiation from the others. Table 2-1 is a synopsis of these discriminators. How do you know whether to include or exclude fibrous dysplasia if it can look like almost anything? Experience is the best guideline. In other words, look in a few texts and find as many different examples as you can; get a feeling for what fibrous dysplasia looks like. A few examples are shown in Figures 2-1 to 2-6, but pouring over another text for 10 to 15 minutes will be time well spent. FIGURE 2-1 FIGURE 2-2 FIGURE 2-3 FIGURE 2-4 FIGURE 2-5 FIGURE 2-6 Fibrous dysplasia will not have periostitis associated with it; therefore, if periostitis is present, you can safely exclude fibrous dysplasia. It would be possible to have a pathologic fracture through an area of fibrous dysplasia, which then had periostitis, but I have never seen this occur. Fibrous dysplasia virtually never undergoes malignant degeneration and should not be a painful lesion in the long bones unless there is a fracture. Fibrous dysplasia can be either monostotic (most commonly) or polyostotic and has a predilection for the pelvis, proximal femur, ribs, and skull. When it is present in the pelvis, it is invariably present in the ipsilateral proximal femur (Figures 2-3 and 2-4). I have seen only one case in which the pelvis was involved with fibrous dysplasia and the proximal femur was spared. The proximal femur, however, may be affected alone, without involvement in the pelvis (Figures 2-5 and 2-6). When fibrous dysplasia is in the differential diagnosis for a lesion in the tibia, an adamantinoma should also be mentioned (Figure 2-7). An adamantinoma is a malignant tumor that radiographically and histologically resembles fibrous dysplasia. It occurs almost exclusively in the tibia (for unknown reasons) and is rare. Because it is rare, you may choose not to include it in your memory bank—you won’t miss more than one or two in your life, even if you are a busy radiologist. FIGURE 2-7 Polyostotic fibrous dysplasia occasionally occurs in association with café-au-lait spots on the skin (dark-pigmented, frecklelike lesions) and precocious puberty. This complex is called McCune-Albright syndrome. The bony lesions in this syndrome, and even in the simple polyostotic form, often occur unilaterally (i.e., in one half of the body). This does not happen often enough to be of any diagnostic use in differentiating fibrous dysplasia from other lesions. The presence of multiple lesions in the jaw has been termed cherubism, which relates to the physical appearance of the affected child. Such children have puffed out cheeks, producing an angelic look. The jaw lesions in cherubism regress in adulthood. The most common benign cystic lesion of the phalanges is an enchondroma (Figure 2-8). Enchondromas occur in any bone formed from cartilage and may be central, eccentric, expansile, or nonexpansile. They invariably contain calcified chondroid matrix (Figure 2-9, A) except when in the phalanges. If a cystic lesion is present without calcified chondroid matrix anywhere except in the phalanges, I will not include enchondroma in my differential. FIGURE 2-8 FIGURE 2-9 Often it is difficult to differentiate between an enchondroma and a bone infarct. Although some of the following criteria are helpful in separating an infarct from an enchondroma, they are not foolproof. An infarct usually has a well-defined, densely sclerotic, serpiginous border, whereas an enchondroma does not (Figure 2-9, B). An enchondroma often causes endosteal scalloping, whereas a bone infarct will not. It is difficult, if not impossible, to differentiate an enchondroma from a chondrosarcoma. Clinical findings (primarily pain) serve as a better indicator than radiographic findings, and indeed pain in an apparent enchondroma should warrant surgical investigation. Periostitis should not be seen in an enchondroma either. Trying to differentiate an enchondroma from a chondrosarcoma histologically is also difficult, if not impossible at times. Therefore biopsy of an apparent enchondroma should not be performed routinely for histologic differentiation.2 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) criteria for benign versus malignant includes lack of a soft tissue mass and no surrounding T2 high-signal edema in benign enchondromas. Multiple enchondromas occur on occasion, and this condition has been termed Ollier’s disease (Figure 2-10, A). It is not hereditary and does not have an increased rate of malignant degeneration. Older books say that Ollier’s disease has a high rate of malignant degeneration; this is because any chondroid lesion can look malignant when a biopsy is performed and needs to be correlated radiographically and clinically. The presence of multiple enchondromas associated with soft tissue hemangiomas is known as Maffucci’s syndrome (Figure 2-10, B). This syndrome also is not hereditary; however, it is characterized by an increased incidence of malignant degeneration of the enchondromas. FIGURE 2-10 EG, unfortunately for radiologists, has many appearances. It can be lytic or blastic, may be well defined or ill defined (Figures 2-11 and 2-12), may or may not have a sclerotic border, and may or may not elicit a periosteal response.3 The periostitis, when present, is typically benign in appearance (thick, uniform, wavy) but can be lamellated or amorphous. EG can mimic Ewing’s sarcoma and present as a permeative (multiple small holes) lesion. FIGURE 2-11 FIGURE 2-12

Benign lytic lesions

FEGNOMASHIC

Fibrous dysplasia

Fibrous dysplasia. A predominantly lytic lesion with some sclerosis and expansion is seen in the distal half of the radius in a child. A long lesion in a long bone typifies fibrous dysplasia. Although parts of this lesion indeed have a ground-glass appearance, most of it does not. Expansion and bone deformity like this is commonly seen in fibrous dysplasia.

Fibrous dysplasia. A predominantly lytic lesion with some sclerosis and expansion is seen in the distal half of the radius in a child. A long lesion in a long bone typifies fibrous dysplasia. Although parts of this lesion indeed have a ground-glass appearance, most of it does not. Expansion and bone deformity like this is commonly seen in fibrous dysplasia.

Fibrous dysplasia. The ribs are often involved with fibrous dysplasia, as in this example. When the posterior ribs are involved, the process is often a lytic expansile lesion, whereas when the anterior ribs are involved, it is commonly a sclerotic process.

Fibrous dysplasia. The ribs are often involved with fibrous dysplasia, as in this example. When the posterior ribs are involved, the process is often a lytic expansile lesion, whereas when the anterior ribs are involved, it is commonly a sclerotic process.

Fibrous dysplasia. An expansile mixed lytic/sclerotic process in the proximal femur is a common pattern for fibrous dysplasia. Note that the supraacetabular region is also involved. The ipsilateral proximal femur is invariably affected when the pelvis is involved with fibrous dysplasia.

Fibrous dysplasia. An expansile mixed lytic/sclerotic process in the proximal femur is a common pattern for fibrous dysplasia. Note that the supraacetabular region is also involved. The ipsilateral proximal femur is invariably affected when the pelvis is involved with fibrous dysplasia.

Fibrous dysplasia. The entire pelvis and proximal femurs are diffusely involved with polyostotic fibrous dysplasia. The pelvis is severely deformed with predominantly lytic lesions. The proximal femurs are involved with both lytic and sclerotic lesions.

Fibrous dysplasia. The entire pelvis and proximal femurs are diffusely involved with polyostotic fibrous dysplasia. The pelvis is severely deformed with predominantly lytic lesions. The proximal femurs are involved with both lytic and sclerotic lesions.

Monostotic fibrous dysplasia. The proximal femur is a common place for monostotic fibrous dysplasia. This presentation is typical and should not be confused with an infection. Some speckled calcification is noted within the lesion that should not be misconstrued as chondroid calcification in an enchondroma.

Monostotic fibrous dysplasia. The proximal femur is a common place for monostotic fibrous dysplasia. This presentation is typical and should not be confused with an infection. Some speckled calcification is noted within the lesion that should not be misconstrued as chondroid calcification in an enchondroma.

Monostotic fibrous dysplasia. Another example of proximal femur involvement that shows a lytic lesion with a thick sclerotic border reminiscent of a chronic infection. This is characteristic of fibrous dysplasia in the hip.

Monostotic fibrous dysplasia. Another example of proximal femur involvement that shows a lytic lesion with a thick sclerotic border reminiscent of a chronic infection. This is characteristic of fibrous dysplasia in the hip.

Adamantinoma. A wild-looking mixed lytic/sclerotic lesion in the tibia that resembles fibrous dysplasia is classic for an adamantinoma. This lesion occurs almost exclusively in the tibia and has some malignant potential. An adamantinoma should always be considered when a lesion resembling fibrous dysplasia is seen in the tibia.

Adamantinoma. A wild-looking mixed lytic/sclerotic lesion in the tibia that resembles fibrous dysplasia is classic for an adamantinoma. This lesion occurs almost exclusively in the tibia and has some malignant potential. An adamantinoma should always be considered when a lesion resembling fibrous dysplasia is seen in the tibia.

Enchondroma and eosinophilic granuloma

Enchondroma

Enchondroma. A benign lytic lesion in the hand is an enchondroma until proved otherwise. This is a common presentation of an enchondroma. Enchondromas in any other part of the body should contain some calcified chondroid matrix before they are included in the differential. However, calcified chondroid matrix is unusual in the phalanges.

Enchondroma. A benign lytic lesion in the hand is an enchondroma until proved otherwise. This is a common presentation of an enchondroma. Enchondromas in any other part of the body should contain some calcified chondroid matrix before they are included in the differential. However, calcified chondroid matrix is unusual in the phalanges.

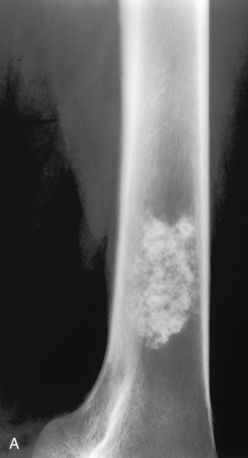

A, Enchondroma. A lesion in the distal femur is seen with irregular speckled calcification typical of chondroid matrix. This is virtually pathognomonic of an enchondroma. A chondrosarcoma could have an identical appearance but should be painful for consideration in the differential diagnosis. A bone infarct can be similar in appearance to an enchondroma. B, Bone infarcts. Bilateral lytic lesions in the femurs are noted with a densely calcified serpiginous border characteristic of bone infarcts. Compare these lesions with (A), which does not have a well-defined serpiginous border. Often the differentiation between bone infarcts as in this example and an enchondroma (A) is not so clear-cut. (Case courtesy of Dr. Hideyo Minagi.)

A, Enchondroma. A lesion in the distal femur is seen with irregular speckled calcification typical of chondroid matrix. This is virtually pathognomonic of an enchondroma. A chondrosarcoma could have an identical appearance but should be painful for consideration in the differential diagnosis. A bone infarct can be similar in appearance to an enchondroma. B, Bone infarcts. Bilateral lytic lesions in the femurs are noted with a densely calcified serpiginous border characteristic of bone infarcts. Compare these lesions with (A), which does not have a well-defined serpiginous border. Often the differentiation between bone infarcts as in this example and an enchondroma (A) is not so clear-cut. (Case courtesy of Dr. Hideyo Minagi.)

A, Ollier’s disease. Multiple lytic lesions in the hand—multiple enchondromas—are seen in this patient. This is known as Ollier’s disease. B, Maffucci’s syndrome. Multiple enchondromas associated with soft tissue hemangiomas are seen in the hand in this patient. This is Maffucci’s syndrome. Note the multiple rounded calcifications in the soft tissues, which are phleboliths in the hemangiomas.

A, Ollier’s disease. Multiple lytic lesions in the hand—multiple enchondromas—are seen in this patient. This is known as Ollier’s disease. B, Maffucci’s syndrome. Multiple enchondromas associated with soft tissue hemangiomas are seen in the hand in this patient. This is Maffucci’s syndrome. Note the multiple rounded calcifications in the soft tissues, which are phleboliths in the hemangiomas.

Eosinophilic granuloma

Eosinophilic granuloma. A well-defined lytic lesion in the midshaft of a femur in a child. At biopsy this was shown to be eosinophilic granuloma. This is an entirely nonspecific pattern that could easily represent a focus of infection or one of several other processes. Because the lesion is present in a child, eosinophilic granuloma must be included in the differential diagnosis.

Eosinophilic granuloma. A well-defined lytic lesion in the midshaft of a femur in a child. At biopsy this was shown to be eosinophilic granuloma. This is an entirely nonspecific pattern that could easily represent a focus of infection or one of several other processes. Because the lesion is present in a child, eosinophilic granuloma must be included in the differential diagnosis.

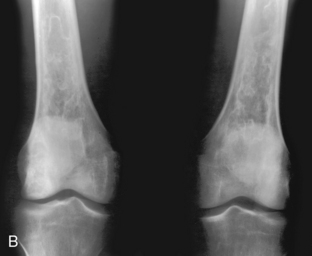

Eosinophilic granuloma. A predominantly lytic process with some sclerosis is seen in the proximal femur in a child. Again, this case would have a long differential diagnosis. Eosinophilic granuloma must be mentioned because the patient is younger than age 30. In this example the zone of transition is narrow and the lesion appears benign, but eosinophilic granuloma can have an aggressive appearance and mimic a sarcoma.

Eosinophilic granuloma. A predominantly lytic process with some sclerosis is seen in the proximal femur in a child. Again, this case would have a long differential diagnosis. Eosinophilic granuloma must be mentioned because the patient is younger than age 30. In this example the zone of transition is narrow and the lesion appears benign, but eosinophilic granuloma can have an aggressive appearance and mimic a sarcoma.![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Benign lytic lesions