Benign Masses

Although we place much emphasis on detecting microcalcifications and anguish over their characterization, we need to recognize that most invasive ductal carcinomas present as a mass. In contrast, when associated with malignancy, microcalcifications usually reflect intraductal, noninvasive breast cancer. Our primary goal with screening mammography is the recognition or perception of a possible mass or distortion related to an underlying mass. Our characterization of masses and management recommendations are predicated on spot compression, rolled or microfocus spot magnification views, and breast ultrasound. In some women, what appears to be a mass on screening images is shown to be superimposition of normal glandular tissue, and what appears as an innocuous asymmetry is identified as likely malignant with further workup. By integrating patient history; clinical, mammographic, and ultrasonographic findings; and an understanding of breast histopathology, it is possible to approximate a diagnosis and have significant confidence in the appropriate management recommendation.

Relevant history is reviewed in evaluating and managing women with a breast mass. Women with a personal history of breast cancer, or a history of breast cancer involving a first-degree relative (mother, father, daughter, sister), are at increased risk for developing breast cancer. This risk is increased if the relative developed breast cancer premenopausally or had bilateral breast cancer. The age and menopausal status of the patient, hormone replacement therapy, and physical findings should be known and factored in the formulation of a differential (Box 6.1).

In women older than 30 years of age presenting with a focal finding (e.g., lump, dimpling, focal tenderness), a metallic BB is used to mark the area of concern, and mediolateral oblique (MLO) and craniocaudal (CC) views are obtained bilaterally (1). A spot tangential view of the focal finding is also obtained. Correlative physical examination and ultrasound are done. Ultrasonography is not absolutely indicated if completely fatty tissue is imaged and it correlates to the site of concern to the patient.

Physical examination and ultrasonography are done in women who are pregnant, lactating, or younger than 30 years of age and present with a lump. If any concerns persist after this initial evaluation, an MLO may be done to exclude calcifications associated with an intraductal carcinoma that may not be apparent on ultrasound. If an underlying malignancy is suspected, mammographic images are obtained to evaluate the patient fully.

As defined by the American College of Radiology Breast Imaging and Reporting Data System (BI-RADS), a mass is a “space occupying lesion seen in two different projections.” This is to be distinguished from density, a term used “if a potential mass is seen in only one projection … until it is three dimensionally confirmed” (2). Masses are three dimensional and have a bulging or convex contour and an abrupt density change at the margin. They may produce architectural distortion and have associated calcifications. Depending on location,

size, internal matrix, and surrounding tissue, the mass may be palpable. Asymmetric tissue is planar, changing significantly between different projections; is scalloped; is inhomogeneous; and has a gradual density change at the margins. It is not palpable (3).

size, internal matrix, and surrounding tissue, the mass may be palpable. Asymmetric tissue is planar, changing significantly between different projections; is scalloped; is inhomogeneous; and has a gradual density change at the margins. It is not palpable (3).

Box 6.1: Breast Masses: Relevant History

Personal history of breast (or other malignancy, e.g., ovarian cancer)

Family history of breast cancer

First-degree relatives

Premenopausal

Bilateral

Patient age (incidence of breast cancer increases with advancing age, and differential considerations change depending on age)

Menopausal status (tumor sojourn time is shorter in premenopausal women)

Hormone replacement therapy

Tamoxifen use

Physical findings

“Lump”

Focal tenderness

Skin dimpling

Nipple retraction

Spontaneous nipple discharge

History of surgical procedures involving the breast

Prior breast biopsy with diagnosis of high-risk marker lesion

Atypical ductal hyperplasia

Lobular neoplasia (lobular carcinoma in situ)

Compression, rolled, and magnification views done with the spot compression paddle are used to establish the shape, margins, and density of breast masses. Round, oval, lobular, and irregular (if “shape cannot be characterized”) are the terms in BI-RADS to describe the shape of a mass. Circumscribed, microlobulated, obscured (margins “hidden by superimposed or adjacent normal tissue”), indistinct, and spiculated are the terms used to describe the margins of a mass. The x-ray attenuation or density of a mass is described as high, equal, low (but not fat containing), or fat containing (radiolucent) and is relative to an equal volume of fibroglandular tissue (2) (Table 6.1).

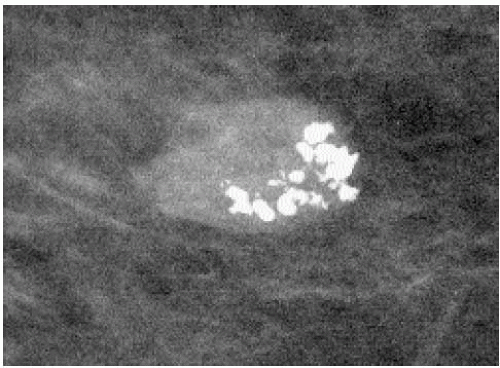

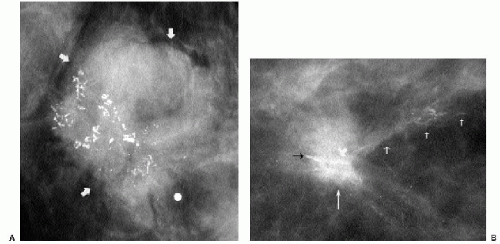

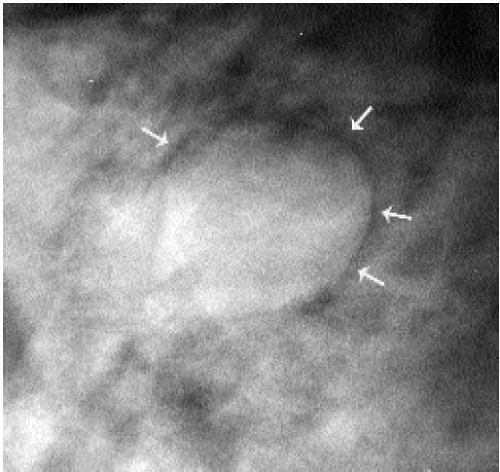

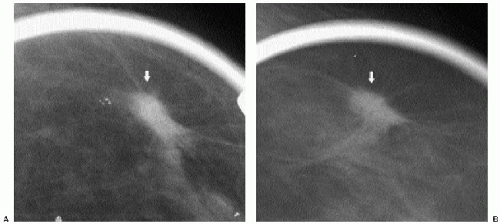

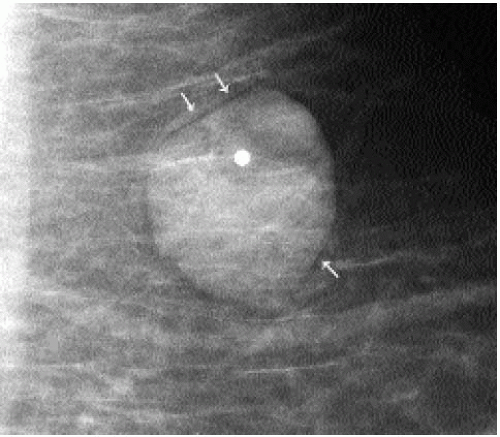

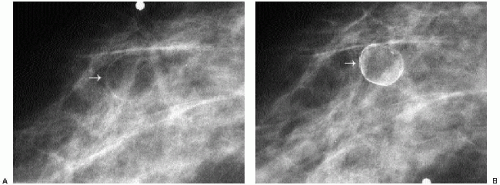

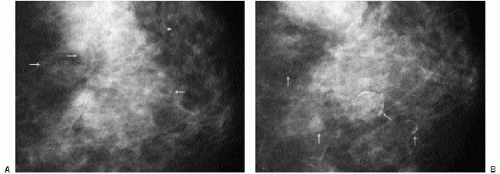

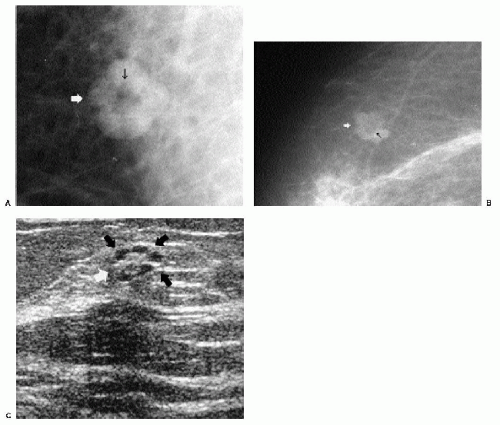

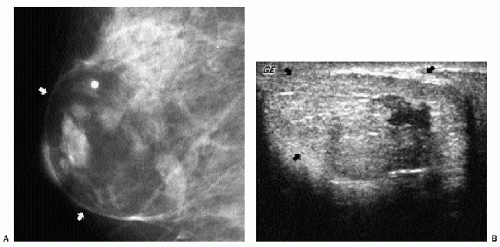

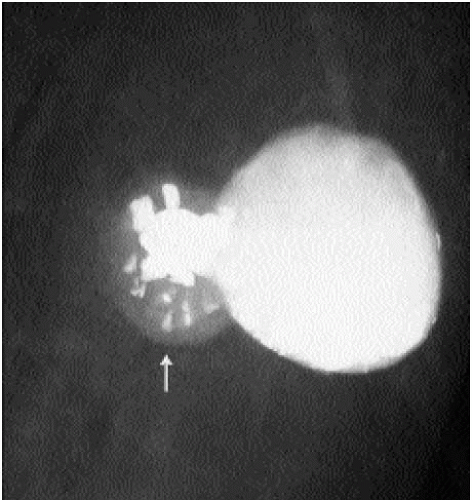

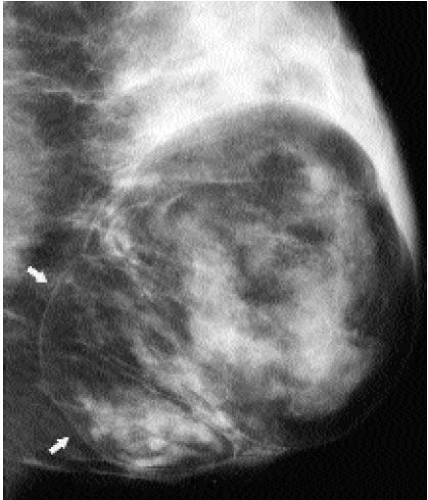

Additional features to consider when evaluating masses are listed in Box 6.2. Establishing the presence of associated calcifications and their morphology is helpful in assessing the etiology of a mass. Benign calcifications are usually associated with benign masses (Figure 6.1). If malignant-appearing calcifications are associated with a mass, then invasive ductal carcinoma with an associated intraductal component is the most likely diagnosis (Figure 6.2). Likewise, establishing the presence of satellite lesions is helpful (Figure 6.3). Although maligned, the halo sign is a good indicator of benignity (4, 5, 6). The halo sign is defined narrowly as a 1-mm sharp lucency surrounding or partially surrounding a mass (Figure 6.4). Not all masses with a true halo are benign, but many are (4,5). The halo sign is probably as good a sign of benignity as spiculation is a sign of malignancy. The halo sign may reflect active changes in the size of the mass.

Table 6.1: American College of Radiology, Lexicon Terms for Masses | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Box 6.2: Additional Features of Masses to Consider

Features of associated calcifications

Effects on surrounding tissue

Architectural distortion

“Halo” sign

Satellite lesions

Multiple lesions

Stability (previous films)

The presence of multiple masses with similar mammographic features is suggestive of benignity. However, do not be lulled into a false sense of security by multiplicity. Women with multiple masses can develop breast cancer. It has been reported that since the frequency of cancer development among women not recalled for evaluation of multiple masses and the stage of the cancers diagnosed in these women are no different than those seen in the general screening population, evaluation of multiple masses appears not to be justified (7). Others advocate ultrasound evaluation in these patients (8). Although controversial, our approach to the patient presenting for the first time with multiple masses is to evaluate each mass as though it were a single finding. Our decisions are based on the mammographic and ultrasonographic features of the masses evaluated. On subsequent mammograms in these patients, we only evaluate new, developing masses.

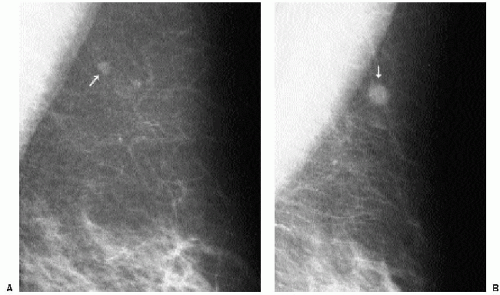

Previous films are useful in the evaluation of masses. Although stability is not an absolute sign of benignity, if a mass with benign features (e.g., well circumscribed) has been present for several years with no change, the likelihood of malignancy is low, and recommending follow-up in 6 months is not appropriate. If the mass has features of malignancy (e.g., spiculation, distortion) that are not explained easily (e.g., prior trauma or surgery at the site), it may represent a low-grade invasive lesion, and biopsy is indicated (Figure 6.5).

In selecting prior films for comparison, try to use films from at least 2 years previously, if available. Subtle changes may not be apparent from one year to the next but may be striking when comparison is made to studies from 2 or 3 years previously.

In selecting prior films for comparison, try to use films from at least 2 years previously, if available. Subtle changes may not be apparent from one year to the next but may be striking when comparison is made to studies from 2 or 3 years previously.

When reviewing prior films, use films from at least 2 or 3 years previously because subtle changes may not be apparent from one year to the next. Also, if available, review several years’ worth of studies because benign lesions can fluctuate.

SKIN MASSES

Masses on the skin include moles, accessory nipples, skin tags, sebaceous cysts, and neurofibromas. They can often be distinguished from intraparenchymal lesions because they are partially or completely outlined by air, seen as a thin curvilinear lucency surrounding the margins of the mass that protrude beyond the skin (Figure 6.6); this lucency is lost where the lesion attaches to the skin (see later). In some women, talc, calcification, or air outlines the crevices of moles (Figure 6.7). We mark skin lesions with a metallic BB before taking any films so that we do not call a patient back unnecessarily for a skin lesion (Figure 6.8).

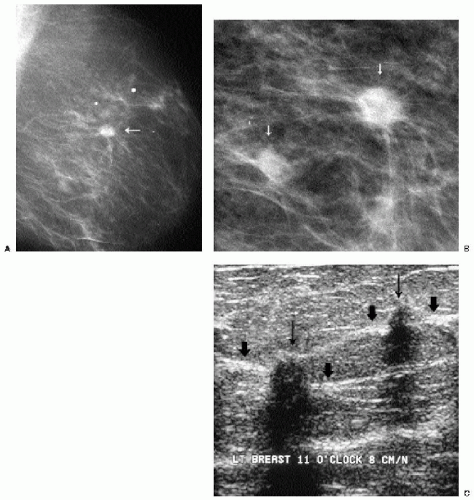

Sebaceous cysts are common, often palpable, sharply marginated intradermal masses that may develop calcifications (Figure 6.9) and undergo changes in size from one year to the next. On physical examination, these may be visible, causing a smooth skin bulge, and the orifice of the gland may be visible as a blackhead. If squeezed, a white, thick, cheesy material may be expressed. If inflamed, incision and drainage may be needed. Complete removal of the cyst wall is required; otherwise, they recur. Mammographically, these lesions can be well-circumscribed, or when inflamed, the margins may be indistinct (Figure 6.10) or spiculated (Figure 6.11A); associated calcifications may be present. On spot tangential views, they are localized to the skin (Figure 6.10B). Ultrasonographically, they are intradermal, anechoic, hypoechoic, or echogenic, often with posterior acoustic enhancement (Figure 6.10C). With manipulation of the transducer, the skin track can be identified in some patients (Figure 6.11B).

Multiple skin lesions, diffusely involving the skin bilaterally, are seen clinically in patients with neurofibromatosis. These lesions may increase in size and number as the patient ages. Mammographically, the skin lesions are well circumscribed and partially or completely outlined by air (Figure 6.12). Evaluation of the breast parenchyma may be difficult because of the skin lesions. Extra care should be used to disregard the obvious benign findings in search of a possible unsuspected malignancy in these patients.

Box 6.3: Fat (Radiolucent) Density Masses

Lipoma

Oil cyst

Box 6.4: Mixed-Density Masses

Intramammary lymph nodes

Fibroadenolipomas (hamartomas)

Fat necrosis, oil cysts

Galactoceles

Postoperative or posttraumatic fluid collections (hematomas, seromas)

FAT-CONTAINING LESIONS

Fat-containing lesions in the breast are benign (1,3). These masses can be completely fatty (Box 6.3) or mixed in density (Box 6.4). Although ultrasonographic findings are described, the diagnosis is reliably established when either completely lucent or mixed-density masses are seen mammographically.

LIPOMAS

Patients with lipomas can be asymptomatic or present with a hard or soft, mobile, palpable superficial mass. A well-circumscribed, radiolucent mass with a thin fibrous capsule is detected mammographically (Figure 6.13). Although the diagnosis is reliably made on

mammographic findings, a well-circumscribed mass with a homogeneously hypoechoic to hyperechoic echotexture is imaged on ultrasound (9) (Figure 6.14). Histologically, these lesions are characterized by the presence of mature lipocytes surrounded by a thin capsule. If otherwise asymptomatic, no intervention or short-term follow-up is indicated (10,11).

mammographic findings, a well-circumscribed mass with a homogeneously hypoechoic to hyperechoic echotexture is imaged on ultrasound (9) (Figure 6.14). Histologically, these lesions are characterized by the presence of mature lipocytes surrounded by a thin capsule. If otherwise asymptomatic, no intervention or short-term follow-up is indicated (10,11).

Figure 6.13 Lipoma. A radiolucent mass with a thin fibrous capsule (thick arrows) diagnostic of a lipoma. Category 2. Benign dystrophic calcifications are present (thin arrows). |

OIL CYSTS

Oil cysts are radiolucent, solitary (Figure 6.15A) or multiple (Fig 6.16A), unilateral or bilateral masses. They vary, and can decrease, in size, resolving completely in some patients on subsequent mammograms. They are idiopathic or develop in areas of prior trauma or surgery and, in this setting, probably represent end-stage fat necrosis. Some women develop mural calcifications, resulting in lucent-centered (or eggshell) calcification (Figures 6.15B and 6.16B); whereas in others, the mural calcifications are seen en phase having a coarse, irregular, curvilinear appearance. In most women, oil cysts are asymptomatic, noted incidentally on screening mammography. Some patients may present describing a discrete, hard mass that is correlated to an oil cyst mammographically. In this situation, it is important to assure the patient and referring physician that the palpable finding is an oil cyst requiring no intervention or follow-up. Although the diagnosis is made mammographically and ultrasonography is not indicated, the ultrasonographic appearance of oil cysts is variable. They may be anechoic with through transmission indistinguishable from fluid-containing cysts (Figure 6.17); they may contain internal echoes; or intracystic, solid-appearing components may be seen (Figure 6.18). Sometimes, oil cysts appear solid.

In some women, oil cysts may be more appropriately characterized as mixed-density lesions because of thickened, ill-defined, or spiculated margins or the presence of a round

or oval intracystic mass. With a history of trauma or surgery and if fat (radiolucency) is associated with these masses in two orthogonal projections, no intervention or short-term follow-up is warranted regardless of the spiculated margins or associated nodule (see Fat Necrosis).

or oval intracystic mass. With a history of trauma or surgery and if fat (radiolucency) is associated with these masses in two orthogonal projections, no intervention or short-term follow-up is warranted regardless of the spiculated margins or associated nodule (see Fat Necrosis).

Steatocystoma multiplex (12,13) is a rare condition with an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance associated with multiple intradermal oil cysts scattered over the body but with a predilection for the trunk and upper extremities. Although more commonly seen in men, women with this condition may be found to have multiple oil cysts in the breasts bilaterally.

MIXED-DENSITY MASSES

LYMPH NODES

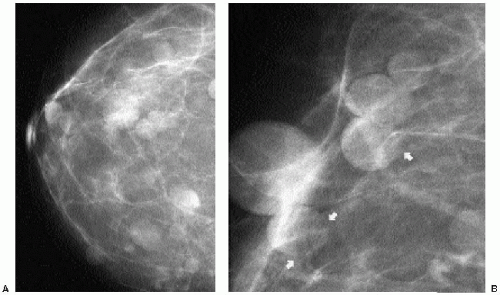

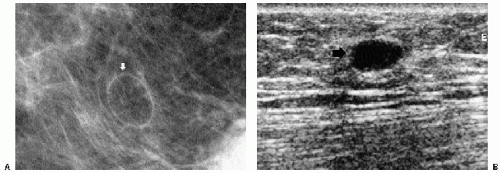

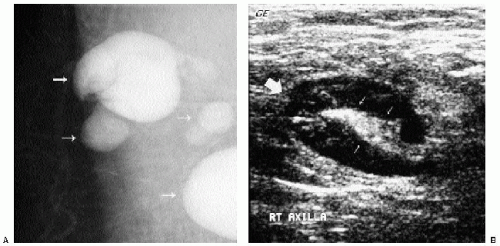

Intramammary and axillary lymph nodes are variable in number, size, density, shape, and location and are seen in as many as 5.4% of women undergoing screening mammography (14). Typically, they are round to oval, well-circumscribed, lobulated masses of mixed density

located in the upper outer quadrants (Figure 6.19A, B); however, they can be found anywhere, including, rarely, the medial aspect of the breast. The presence of a variably sized fatty hilum either centrally or peripherally is required before assuming that a mass in the upper outer quadrant of the breast is a lymph node. Ultrasonographically, lymph nodes are well circumscribed, oval, hypoechoic masses with an area of hyperechogenicity either centrally or peripherally (Figures 6.19C and 6.20). In some patients, they can be strikingly hypoechoic with posterior acoustic enhancement simulating the appearance of cysts. They can fluctuate in size (Figure 6.21) and in some women can disappear only to reappear on subsequent studies.

located in the upper outer quadrants (Figure 6.19A, B); however, they can be found anywhere, including, rarely, the medial aspect of the breast. The presence of a variably sized fatty hilum either centrally or peripherally is required before assuming that a mass in the upper outer quadrant of the breast is a lymph node. Ultrasonographically, lymph nodes are well circumscribed, oval, hypoechoic masses with an area of hyperechogenicity either centrally or peripherally (Figures 6.19C and 6.20). In some patients, they can be strikingly hypoechoic with posterior acoustic enhancement simulating the appearance of cysts. They can fluctuate in size (Figure 6.21) and in some women can disappear only to reappear on subsequent studies.

Benign causes of intramammary and axillary lymphadenopathy (Figure 6.22) are listed in Box 6.5 (15).

Gold particles imaged as high-density, punctate particles mimicking microcalcifications can be seen bilaterally in the axillary and intramammary lymph nodes of women treated for rheumatoid arthritis with gold (16) (Figure 6.23). Coarse calcifications occurring in lymph nodes are often related to granulomatous disease and do not require intervention (Figure 6.24).

Box 6.5: Benign Causes of Intramammary and Axillary Lymphadenopathy

Lymphoid hyperplasia (acute or chronic inflammation)

Collage vascular disorders (rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma, lupus)

Granulomatous disease (sarcoid, tuberculosis)

Human immunodeficiency virus

Dermatopathic (exfoliative or atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, infectious rashes)

Silicone adenopathy

Toxoplasmosis (cat-scratch disease)

Figure 6.24 Granulomatous disease. Dense, coarse calcifications associated with axillary lymph node (arrow) can occasionally be seen in patients with granulomatous disease. |

In a retrospective 5-year review, Lee and colleagues (17) reported unilateral enlargement of axillary or intramammary lymph nodes in 0.2% of their patients with otherwise normal mammograms. In their experience, biopsy is indicated in patients with a history of an underlying malignancy if the lymph node enlarges by more than 100% over baseline. If the woman does not have a history of a malignancy, the lymph node enlargement is small, the node is not palpable, and the node maintains a benign appearance, they suggest clinical and mammographic follow-up. In most of their patients, lymph node enlargement decreased on follow-up studies. Dershaw and associates (18) reported that spiculated adenopathy in patients with breast cancer is suggestive of extranodal extension of tumor into the perinodal fat and portends a poor prognosis. Walsh and co-workers (19) reported that although benign and malignant axillary adenopathy cannot be distinguished mammographically, biopsy should be recommended when nonfatty lymph nodes contain suspicious microcalcifications, are grossly enlarged (they suggest using 45 mm as the criteria for grossly enlarged), or have ill-defined or spiculated margins.

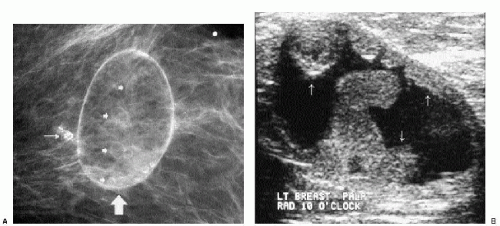

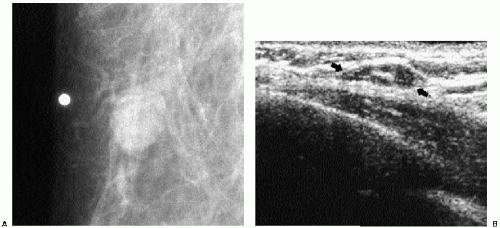

FIBROADENOLIPOMAS (HAMARTOMAS)

Fibroadenolipomas (FALs), or hamartomas, are characterized by the presence of a pseudocapsule within which fatty, glandular, and fibrous elements are admixed. This appearance has led some to describe them as a “breast within a breast” (Figure 6.25). The overall density of these lesions is variable depending on the proportions of fat and glandular tissue. In some women, a FAL may enlarge and present as a palpable mass (Figure 6.26). Because the lesions are made up of otherwise normal breast tissue, breast cancer of any type can arise in hamartomas (20). Development of pleomorphic calcifications and increasing density, particularly if ill defined or spiculated, in a FAL should prompt an imaging-guided biopsy (Figure 6.27). If the patient presents with a palpable mass in a FAL, imaging guidance is helpful in targeting areas of soft tissue in the FAL; otherwise, false-negative results may occur if fatty elements are sampled. On ultrasound, these lesions can be distinguished from the surrounding glandular tissue and have a heterogenous echotexture with admixed areas of hypoechogenicity and hyperechogenicity.

Because FALs contain normal breast tissue, breast cancer of any type can arise within them.

Figure 6.25 Fibroadenolipoma. A mixed-density mass. A thin pseudocapsule is seen (arrows) enclosing fatty and glandular elements. Some mass effect is seen superiorly. Category 2. |

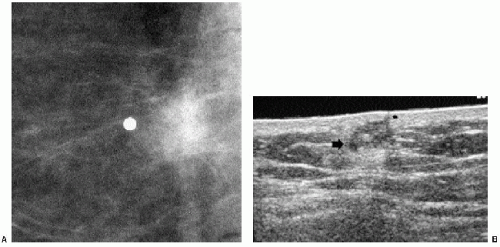

FAT NECROSIS

Trauma or surgery resulting in the release of fatty substances in the breast stroma can lead to an inflammatory response commonly characterized, in the acute setting, by a spiculated mass with architectural distortion (Figure 6.28); skin thickening and retraction may be present. Alternatively, a mixed-density mass with indistinct margins (Figure 6.29) or an irregular area of density (Figure 6.30) may be seen. As the inflammatory response subsides, the mammographic and ultrasonographic features of the lesion usually evolve. In some women, the spiculated or mixed-density mass becomes less dense, and a fatty center develops (Figure 6.31); as the ill-defined soft tissue component resolves, a smooth, thin-walled oil cyst may be all that remains. The progression from dense, spiculated mass to oil cyst is appreciated as films are viewed sequentially. In the intermediate stages, densities or nodules may be seen within the oil cyst. Calcifications developing in areas of fat necrosis can be dystrophic in appearance or, early in their formation, linear with irregular margins and pleomorphism indistinguishable from the microcalcifications associated with comedo necrosis in ductal carcinoma in situ. In other women, fat necrosis resolves completely with no residual abnormality seen on subsequent studies (21). Less common appearances for fat necrosis include development of islands of parenchymal asymmetry (Figure 6.32) or trabecular thickening forming a fine reticular pattern (Figure 6.33).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree