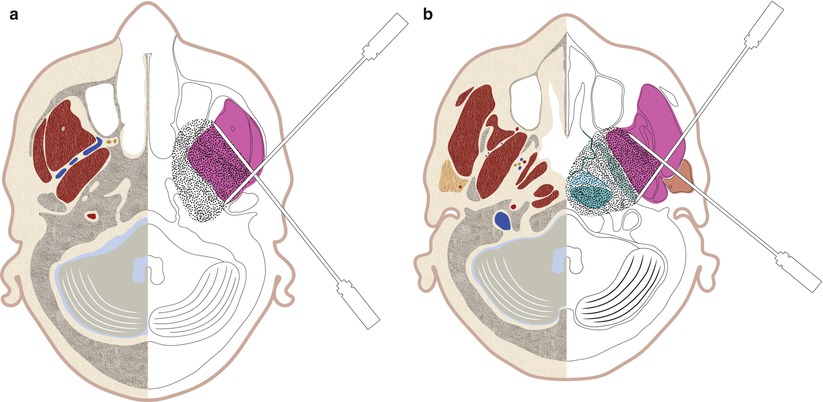

Fig. 9.1

(a–h). Schematic drawings showing axial cross-sectional anatomy at various levels in the head and neck region. In each figure, the anatomic structures are shown on the left and the spaces on the right. (a) Skull base level. (b) Upper maxillary antrum level. (c) Lower maxillary antrum level. (d) Alveolar ridge level. (e) Mandibular level. (f) C4 vertebral level. (g) C6 vertebral level. (h) C7 vertebral level

The parapharyngeal space (Fig. 9.1a–e) extends from the hyoid bone inferiorly to the skull base superiorly. The parapharyngeal space is bounded anteriorly by the masticator space, laterally by the deep parotid space, medially by the pharyngeal mucosal space, posteriorly by the carotid space, and posteromedially by the lateral extension of the retropharyngeal space. The major structures that are located in the parapharyngeal space include the internal maxillary, middle meningeal, and ascending pharyngeal arteries; the pterygoid venous plexus; and branches of the mandibular nerve. The pharyngeal mucosal space (Fig. 9.1a–e) is located on the airway side of the buccopharyngeal fascia in the nasopharynx and oropharynx and contains mucosa, lymphoid tissue, minor salivary glands, and pharyngeal constrictor muscles.

The masticator space (Fig. 9.1a–e) can be divided into two components: the infratemporal fossa below the zygomatic arch and the temporal fossa above the arch. The masticator space is bordered by the buccal space anteriorly, the parotid space posteriorly, and the parapharyngeal space posteromedially. Apart from the musculoskeletal structures (the medial and lateral pterygoid, masseter, temporalis muscles, and mandible), the inferior alveolar branch of the mandibular nerve and the inferior alveolar vessels traverse the masticator space.

The contents of the carotid space (Fig. 9.1a–h) include the common or the internal carotid artery (depending on the level); the internal jugular vein; sympathetic plexus; cranial nerves IX, X, XI, and XII in the nasopharyngeal portion; cranial nerve X in the oropharyngeal and infrahyoid neck; and lymph nodes.

The parotid space (Fig. 9.1b–e) is located directly lateral to the parapharyngeal space and posterolateral to the masticator space, extending from the level of the external auditory canal down to the angle of the mandible. The posterior belly of the digastric muscle separates the medial portion of the parotid space from the anterolateral aspect of the carotid space. The parotid space contains the parotid gland, facial nerve, external carotid artery, retromandibular vein, and lymph nodes.

The retropharyngeal space (Fig. 9.1a–h) is a midline space that contains fat and lymph nodes only. This space is bordered by the pharyngeal mucosal space anteriorly, the carotid space laterally, and the prevertebral portion of the perivertebral space posteriorly. The perivertebral space (Fig. 9.1a–h) lies beneath the deep layer of deep cervical fascia and can be divided into the prevertebral and paravertebral portions. The prevertebral portion contains the prevertebral muscles, the vertebral artery and vein, the scalene muscles, the brachial plexus, the phrenic nerve, and the vertebral body, transverse process, and pedicle. The paravertebral portion of this space contains the paravertebral muscles and posterior elements of the cervical vertebrae.

In the infrahyoid neck (Fig. 9.1f–h), the visceral space is bounded by the middle layer of the deep cervical fascia and contains the thyroid and parathyroid glands, larynx, hypopharynx, esophagus, trachea, recurrent laryngeal nerve, and lymph nodes. The posterior cervical space is located posterior to the carotid space and lateral to the perivertebral space and contains the spinal accessory nerve and the preaxillary portion of the brachial plexus. No important structure is present in the anterior cervical space, which is located lateral to the visceral space and anterior to the carotid space.

Approaches for Skull Base, Head, and Suprahyoid Neck Lesions

Subzygomatic (Infratemporal, Transcondylar, Sigmoid Notch) Approach

The subzygomatic approach is ideally suited for the biopsy of lesions in different parts of the masticator space. This approach can also be used for sampling lesions in the parapharyngeal, pharyngeal mucosal, and retropharyngeal spaces and for the prevertebral portion of the perivertebral space. Lesions in the suprazygomatic portion (temporal fossa) of the masticator space and skull base, including the pterygopalatine fossa region, can also be accessed using this approach.

In the subzygomatic approach, the needle is inserted below the zygomatic arch and advanced through the intercondylar (mandibular) notch between the coronoid process anteriorly, the mandibular condyle posteriorly, and the superior border of the mandibular ramus inferiorly (Fig. 9.2). The needle can be angulated in various (anterior, posterior, cranial, or caudal) directions, allowing access to multiple target sites (Figs. 9.3 and 9.4). The needle traverses the masticator and the parapharyngeal spaces during biopsies of lesions located in the pharyngeal mucosal, retropharyngeal, and prevertebral spaces and skull base.

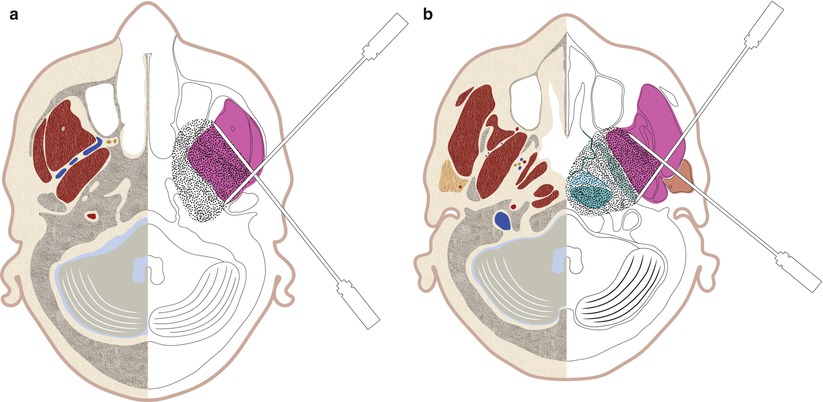

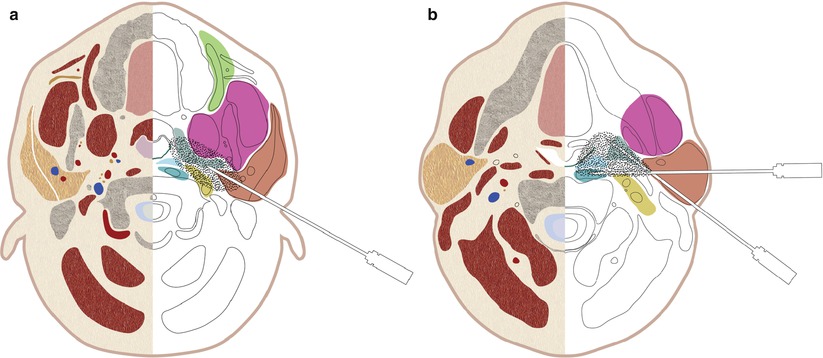

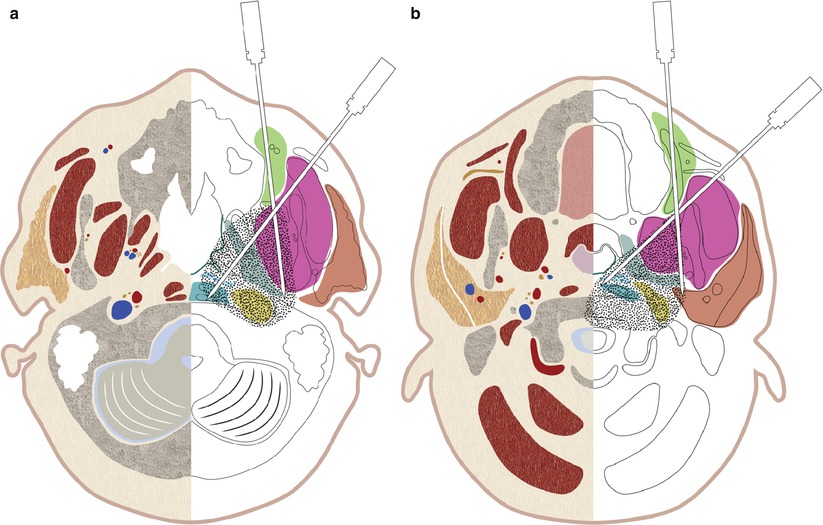

Fig. 9.2

Schematic drawing showing possible needle trajectories for subzygomatic approach at the (a) skull base level and (b) upper nasopharyngeal level

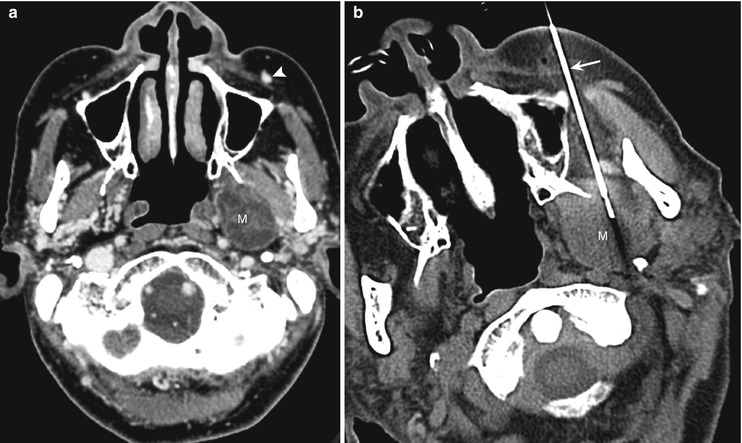

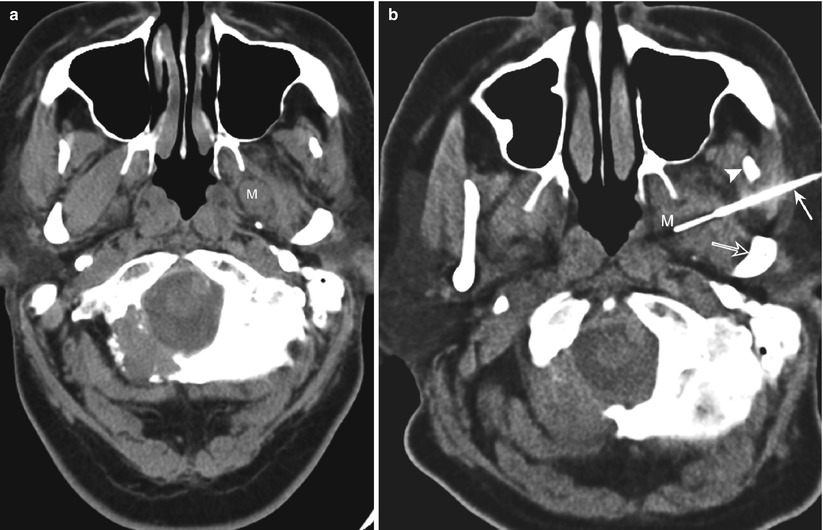

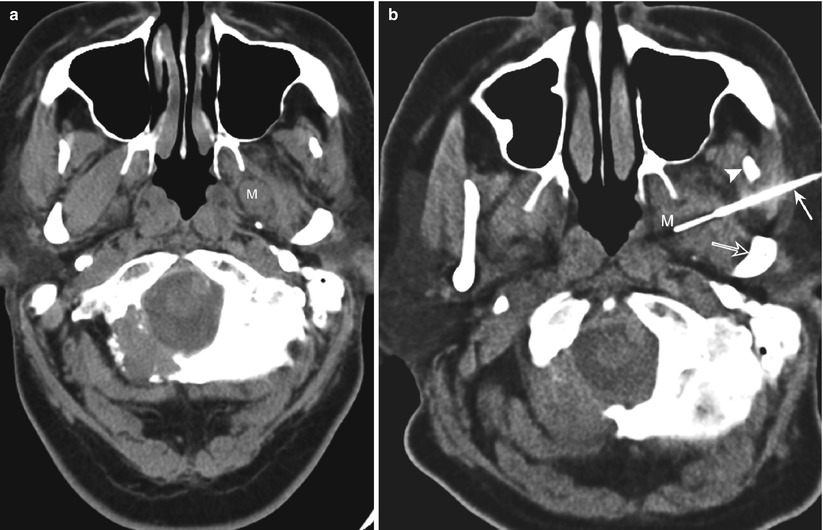

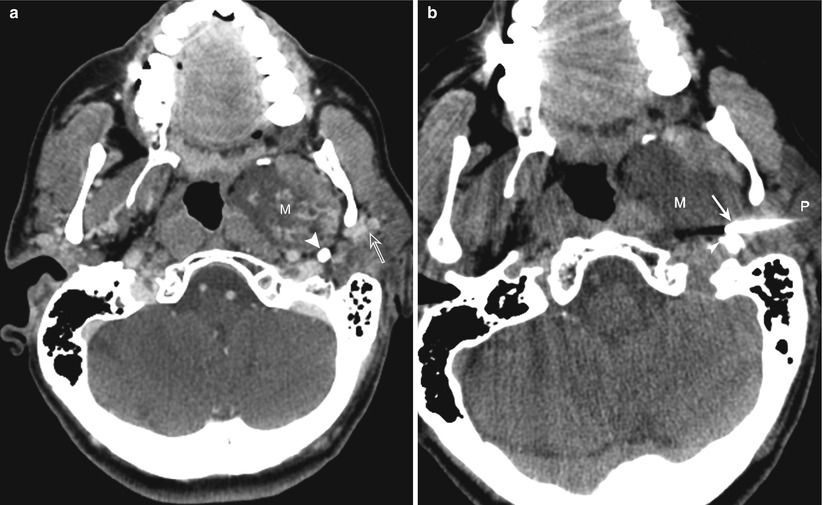

Fig. 9.3

Subzygomatic approach. (a) Computed tomography (CT) scan shows a soft-tissue mass (M) in the parapharyngeal space. (b) CT scan shows the biopsy needle (arrow) that was advanced between the coronoid process (arrowhead) and mandibular condyle (open arrow) into the parapharyngeal mass (M)

Fig. 9.4

Subzygomatic approach. CT scan shows the biopsy needle advanced under the zygoma (Z) for biopsy of a soft-tissue mass in the pterygomaxillary space (M)

Cranial needle angulation allows the subzygomatic approach to be used for accessing lesions in the skull base and the suprazygomatic portion of the masticator space. Using a triangulation method, the physician estimates the needle angle from contiguous axial CT scans obtained from the level of the planned skin entry site to the level of the target lesion. The needle is inserted below the level of the zygomatic arch and advanced cranially and medially in small increments; axial CT scans are obtained to check the needle tip position and angulation (Fig. 9.5). Alternatively, a change in the degree of neck flexion can bring the target lesion and the skin entry site into the same axial plane, allowing visualization of the entire needle length in a single axial CT image.

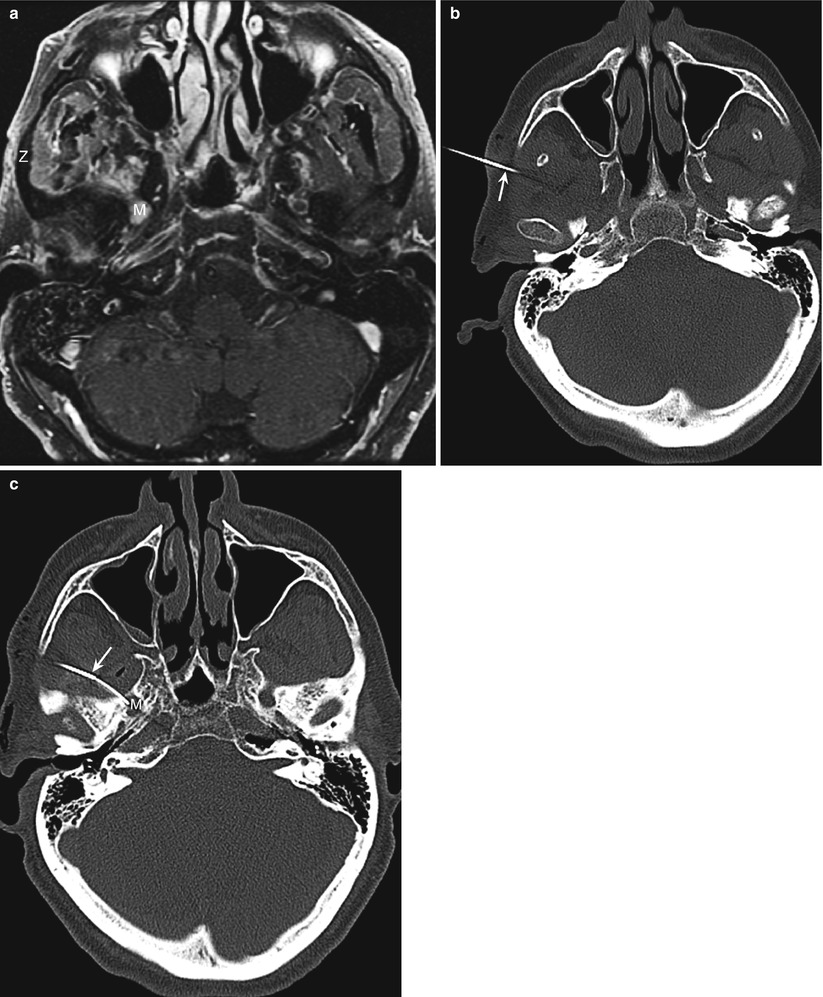

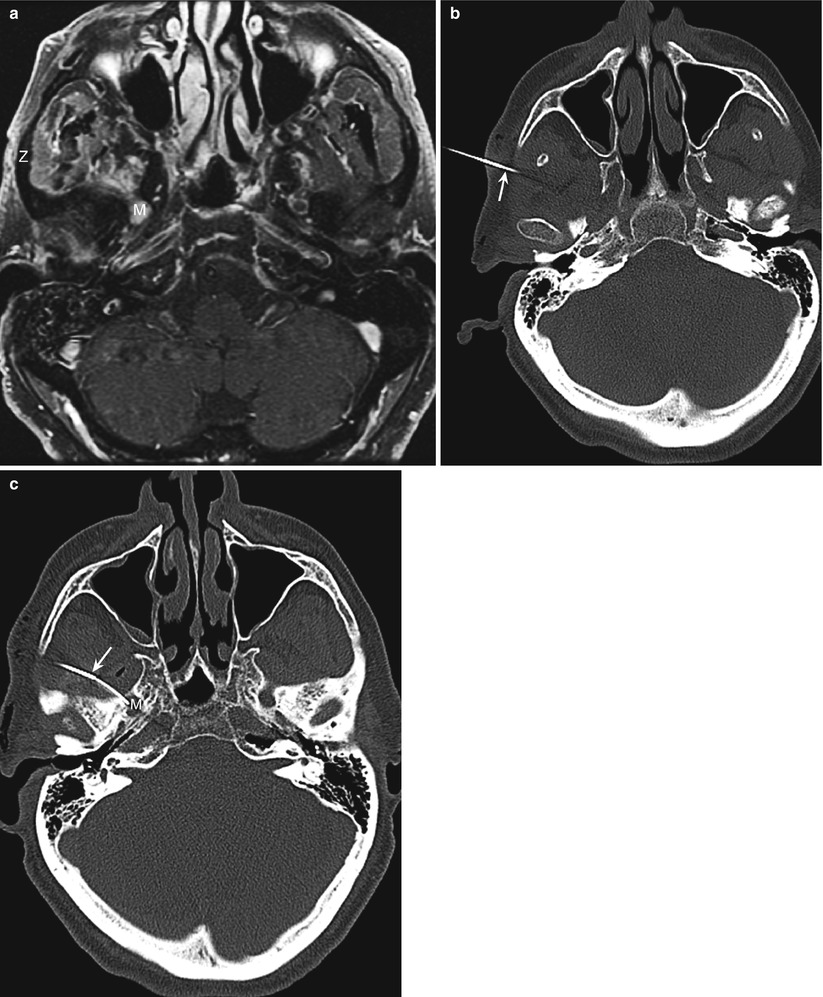

Fig. 9.5

Subzygomatic approach. (a) Magnetic resonance image shows a soft-tissue mass (m) in the right foramen ovale. A direct lateral approach is precluded by the zygomatic arch (Z). (b) Computed tomography (CT) scan shows the biopsy needle (arrow) inserted at a level caudal to the zygomatic arch. The needle was advanced in a cranial direction using the triangulation method. (c) CT scan at a more cranial level shows a curved 22-gauge needle (arrow) advanced through the guide needle and into the mass (M)

It has been suggested that having the patient keep his or her mouth open, preferably with a bite block, can help open up the space between the mandible and the zygomatic arch, thus facilitating needle insertion; however, in our experience, as in that of others [2], this is rarely necessary.

With the sybzygomatic approach, there is a theoretical risk of injury to the mandibular branch of the trigeminal nerve, the internal maxillary artery and its branches (including the middle meningeal artery), and the pterygoid venous plexus. The maxillary artery arises posterior to the neck of the mandible and is embedded in the parotid gland. The mandibular part runs horizontally forward along the medial surface of the ramus and passes between the neck of the mandible and the sphenomandibular ligament. The pterygoid part ascends obliquely forward and medially, either superficially or deep to the lateral pterygoid muscle, to enter the pterygopalatine fossa through the pterygomaxillary fissure. The middle meningeal artery arises from the mandibular part of the internal maxillary artery and ascends in the posterior part of the sigmoid notch deep to the lateral pterygoid muscle to enter the foramen spinosum. The mandibular nerve exits the cranial cavity through the foramen ovale and descends in the posterior part of the intercondylar notch; the mandibular nerve runs downward medially to the lateral pterygoid muscle and a little anteriorly to the neck of the mandible to enter the inner surface of the mandibular ramus. The pterygoid venous plexus of veins is located partly between the temporalis and lateral pterygoid and partly between the two pterygoid muscles. However, as mentioned earlier, the risk of major injury to the vessels or the nerves is extremely low. A needle inserted posteriorly close to the mandibular condyle and directed anteriorly may occasionally pass through a small anterior portion of the parotid gland, but this usually does not cause problems (Fig. 9.2b).

Retromandibular (Transparotid) Approach

Lesions in the deep parotid space, parapharyngeal space, pharyngeal mucosal space, and lower part of the retropharyngeal space are amenable to biopsy with a retromandibular approach. This approach can also be used for sampling lesions in the carotid sheath if the vessels are displaced medially by the mass.

With the patient in the supine position and his or her head turned to the contralateral side, the needle is inserted posterior to the mandible and anterior to the mastoid process and advanced through the parotid gland (which is located behind the mandible, extending from the external auditory canal to the level of the mandibular angle) toward the target lesion (Fig. 9.6). Care should be taken to identify and avoid the external carotid artery and the retromandibular vein, which are both located within the parotid gland immediately posterior to the mandibular ramus (Fig. 9.6). The external carotid artery is medial of the two vessels. Approximately midway between the tip of the mastoid process and the angle of the mandible, the external carotid artery turns laterally from the carotid sheath and passes anterior to the posterior belly of the digastric muscle to reach the posteromedial surface of the parotid gland. Within the substance of the parotid gland, the external carotid artery ascends behind the condyle and divides into its terminal branches, the superficial temporal and maxillary arteries. The seventh cranial nerve passes just lateral to the retromandibular vein (Fig. 9.1d). The styloid process serves as a useful bony landmark; keeping the needle anterior to the styloid process avoids injury to the internal carotid artery, which is located in a plane posterior to the styloid process (Fig. 9.7). Occasionally, however, medial displacement of the carotid vessels by mass lesions may allow the needle to be advanced posterior to the styloid process.

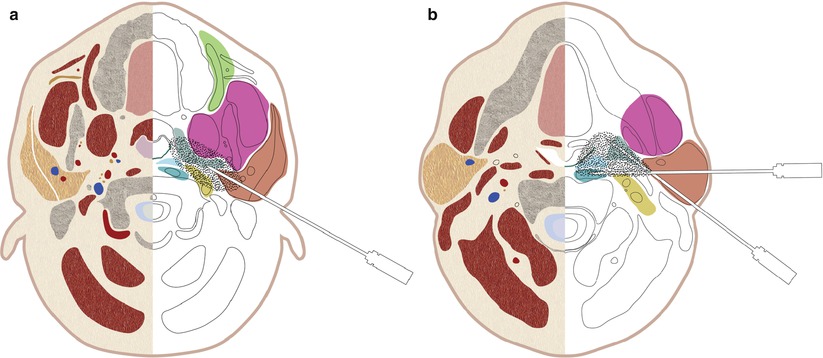

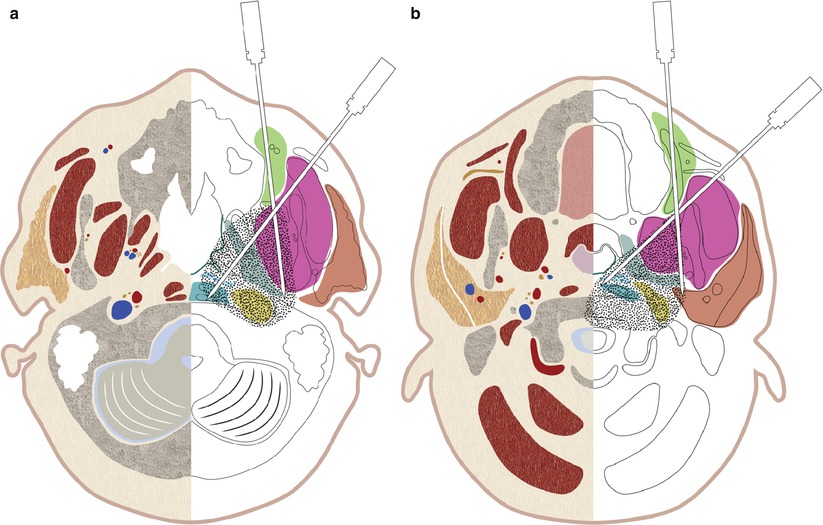

Fig. 9.6

Schematic drawing showing possible needle trajectories for the retromandibular approach at (a) alveolar ridge level and (b) mandibular level

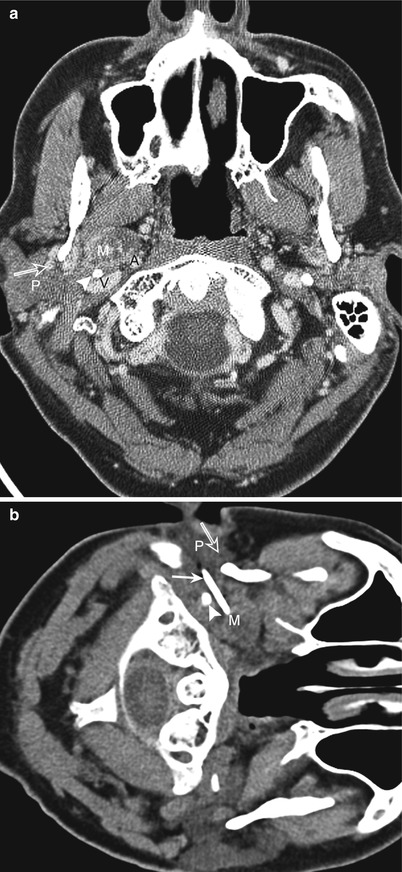

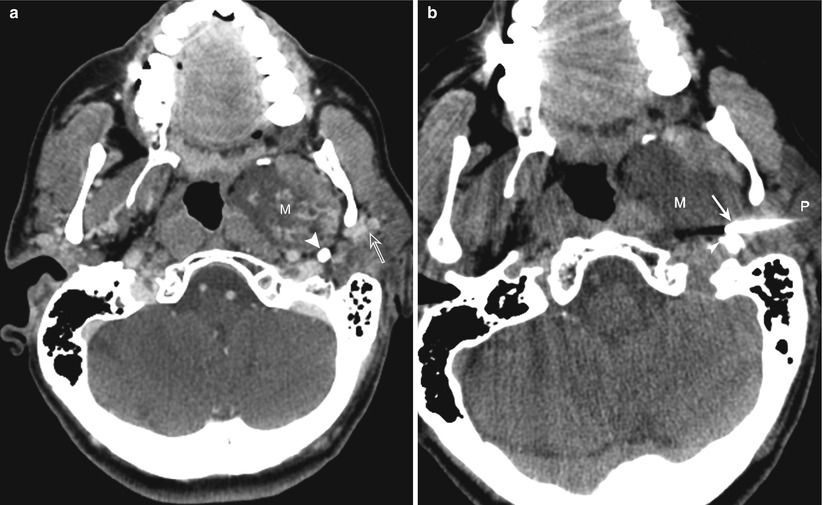

Fig. 9.7

Retromandibular approach. (a) Computed tomography (CT) scan shows a right parapharyngeal mass (M). Note the presence of the external carotid artery and retromandibular vein (open arrow) in the anterior portion of the parotid gland (P). The carotid artery (A) and jugular vein (V) are located posterior to the styloid process (arrowhead). (b) CT scan shows the biopsy needle (arrow) inserted through the parotid gland (P) posterior to the vessels (open arrow). The needle passes anterior to the styloid process (arrowhead) into the mass (M)

The presence of surrounding structures, such as the styloid process, internal carotid artery, mastoid process, and mandible, does not allow much room for needle angulation. Thus, it is difficult to access the skull base, the prevertebral space, the cervical spine, and portions of the retropharyngeal space with this approach (Fig. 9.8). The potential risk of injury to the facial nerve, which courses through the parotid gland, limits the size of the biopsy needle that can be used with this approach. The use of thin needles precludes the option of obtaining a core specimen. For a biopsy of deeper lesions, the needle passes through the parapharyngeal space, and there is a potential risk of injury to the mandibular nerve branches and branches of the internal maxillary artery, such as the middle meningeal and ascending pharyngeal arteries. Yousem et al. [20] pointed out that a transparotid biopsy may occasionally yield salivary gland tissue, which may be confused with a salivary gland neoplasm of the parapharyngeal space. However, we have not encountered this problem in any of our patients.

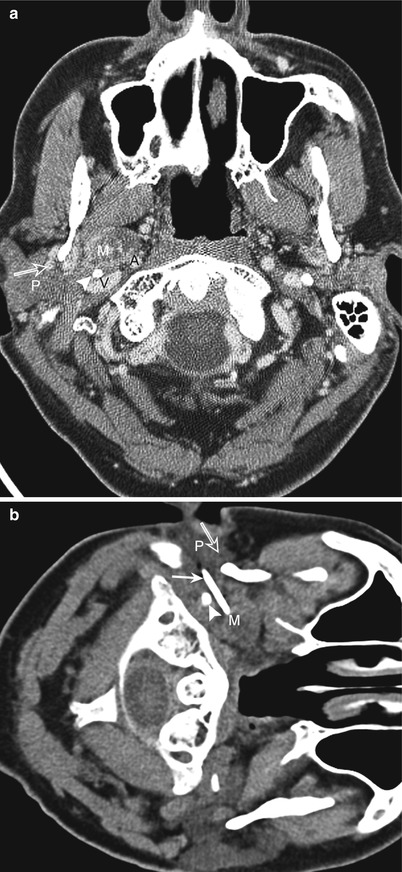

Fig. 9.8

Retromandibular approach. (a) Computed tomography (CT) scan shows parapharyngeal mass (M) located anterior to the styloid process (arrowhead). Note the presence of the external carotid artery and retromandibular vein (open arrow) in the anterior portion of the parotid gland. (b) Presence of vessels in the parotid gland (P) and the styloid process (arrowhead) limits the needle (arrow) angulation, restricting access to the mass (M)

Paramaxillary (Retromaxillary, Buccal Space) Approach

The paramaxillary approach offers safe access to lesions in the infrazygomatic portion of the masticator space, the posterior portions of the parapharyngeal and pharyngeal mucosal spaces, the carotid sheath space, and the deep portion of the parotid space [21, 22]. This approach is particularly useful for lesions in the lateral part of the retropharyngeal (e.g., lateral retropharyngeal node of Rouviere) space and prevertebral portion of the perivertebral space because these lesions are difficult to access by other approaches. The paramaxillary approach can also be used for sampling lesions involving the anterior arch of the first cervical vertebra (C1) and the odontoid and body of the second (C2). In addition, this approach can be used to access the foramen ovale and other skull base lesions by using a cranial needle angulation [23].

For the transfacial paramaxillary approach, the patient is placed in the supine position with his or her head turned to the contralateral side, and the needle is inserted through the buccal space inferior to the zygomatic process of the maxilla and advanced posteriorly between the maxilla (alveolar ridge or sinus) and mandible (Fig. 9.9). It is important to avoid the facial artery, which is easy to identify as it courses in the buccal space (Fig. 9.9). For biopsy of lesions in the masticator and parapharyngeal spaces, the needle passes through the buccinator muscle or anterior portion of the masseter muscle or between them (Fig. 9.10). The needle is advanced through the lateral and medial pterygoid muscles and the parapharyngeal space to biopsy lesions in the retropharyngeal (Fig. 9.11) and carotid space (Fig. 9.12) and C1 and C2 lesions (Fig. 9.13). This approach can also be used to access foramen ovale and other skull base lesions by using cranial needle angulation (Fig. 9.14). Effecting mild hyperextension of the neck by placing padding under the patient’s shoulders brings the skull base lesions and the skin entry site into the same axial plane and makes needle placement and visualization simple.

Fig. 9.9

Schematic drawing showing possible needle trajectories for the paramaxillary approach at (a) maxillary antrum level and (b) alveolar ridge level