Fig. 20.1

Schematic drawing showing axial cross-sectional anatomy at various levels in the pelvic region: (a, b) upper pelvis; (c) upper, (d) mid-, and (e) lower greater sciatic foramen levels

The bony walls of the pelvis consist of the innominate bones anteriorly and laterally and the sacrum and coccyx posteriorly. The abdominal muscles, including the rectus abdominis, external oblique, internal oblique, and transverse abdominal muscles, form the anterior and anterolateral walls of the pelvis. The iliacus and psoas muscles join to form the iliopsoas muscle, which courses anterolaterally through the pelvis, medial to the iliac wing. The greater sciatic foramen is bounded by the iliac bone superiorly, the sacrospinous ligament inferiorly, the sacrum posteriorly, and the ischium anteriorly. The sacrospinous ligament divides the greater sciatic foramen into the superior and inferior portions. The important vasculature and nerve bundles exit the greater sciatic bundle cephalad to the level of the sacrospinous ligament. The piriformis muscle originates from the lateral sacrum, exits the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen, and inserts into the greater trochanter of the femur. The internal obturator muscle forms the lateral wall of the pelvis and the ischiorectal fossa. The gluteal muscles lie posterior to the innominate bones.

Major intrapelvic visceral structures include the urinary bladder, rectum, and sigmoid colon in all patients, the uterus and ovaries in female patients, and the prostate and seminal vesicles in male patients. In addition, the superior portion of the pelvis is occupied by variable amounts of small-bowel loops and the ascending, descending, and sigmoid colon. The uterus is seen as a soft tissue density structure between the bladder and rectum. Although the position of the ovaries is highly variable, they are usually located posterolateral to the uterus, between the external iliac vessels and the ureter. In the upper part of the pelvis, the ureters are anterior to the common iliac vessels and anteromedial to the psoas muscle. The ureters then course inferiorly and posteriorly and at midpelvis level are located posterior to the external iliac vessels, anterior to the internal iliac vessels, and medial to the obturator nerve and artery. At the level of the sciatic foramen, the ureters turn medially toward the lateral angle of the bladder.

The common iliac arteries course downwards and laterally on the anterolateral surface of the fourth and fifth lumbar vertebrae along the medial aspect of the psoas muscles before dividing into the internal and external iliac arteries. The external iliac arteries run along the anteromedial border of the psoas muscles and continue as the common femoral arteries below the level of the inguinal ligament. The internal iliac arteries lie posteriorly, in close relation to the lumbosacral plexus, before dividing into multiple branches at the level of the greater sciatic foramen. The external iliac veins are situated posteromedial to the arteries. The right common iliac vein is posterolateral to the corresponding artery, and the left common iliac vein ascends obliquely from the medial side of the left common iliac artery to pass posterior to the right common iliac artery.

At the level of the pelvis, the testicular/ovarian vessels are located laterally on the psoas muscles and lateral to the ureters. The inferior epigastric artery runs superiorly within the lateral umbilical fold and then along the posterior surface of the rectus abdominis muscle. The deep circumflex iliac artery, along with the accompanying vein, ascends along the anterior abdominal wall laterally near the iliac crest, and it is located just medial to the anterior portion of the iliacus muscle. The superior gluteal arteries arise from the posterior division of the internal iliac vessels and exit the greater sciatic foramen anterior and cephalad to the piriformis muscle. The internal pudendal and inferior gluteal vessels exit the greater sciatic foramen between the piriformis and the coccygeal muscle through the inferior part of the greater sciatic foramen.

The major pelvic nerve trunks can be visualized on CT sections. The greater sciatic nerve is formed from the sacral plexus. The nerve courses inferiorly on the ventral aspect of the piriformis muscle, exits the greater sciatic foramen below the piriformis muscle, and courses immediately posterior to the acetabulum. The femoral nerve can be seen posterior to the psoas muscle at about the L5 level. The nerve travels anteriorly and laterally in a fat plane between the iliacus and psoas muscles; in this location it is difficult to differentiate it from the iliac fascia. The femoral nerve then joins the external iliac vessels and is located lateral to the common femoral artery below the inguinal ligament. The obturator nerve emerges from the medial edge of the psoas muscle above the pelvic brim and courses inferiorly, in front of the internal iliac and obturator vessels and behind the external iliac vessels. The sacral canal contains 5 pairs of sacral nerve roots that exit through the sacral foramina. All the major nerve roots exit anteriorly; the dorsal foramina carry only minor cutaneous nerves.

Approaches to Pelvic Biopsy

Various approaches can be used for percutaneous needle biopsy of deep pelvic lesions using CT guidance. These include the anterior or anterolateral transabdominal approach, transgluteal approach, anterolateral extraperitoneal approach, and transosseous approach (Fig. 20.2a–e). For deep pelvic masses that are not accessible via percutaneous biopsy, the US-guided transvaginal or transrectal approach can be used.

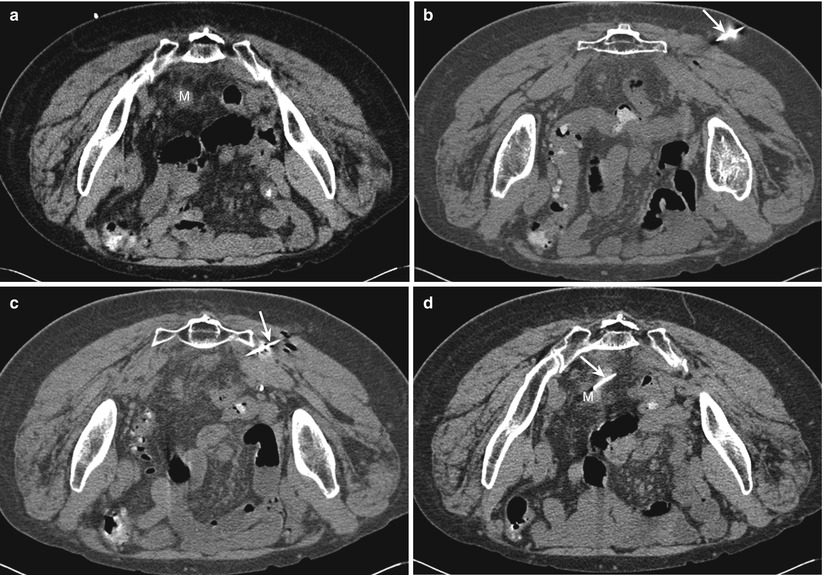

Fig. 20.2

Schematic drawing showing possible needle trajectories for pelvic biopsies at various levels in the pelvic region: (a, b) upper pelvis; (c) upper, (d) mid-, and (e) lower greater sciatic notch levels

Anterior or Anterolateral Transabdominal Approach

For this approach, the needle is inserted through the lower anterior or lateral abdominal wall muscles and the peritoneum. The inferior epigastric vessels located immediately behind the rectus abdominis muscle and the deep circumflex iliac vessels that are located more laterally are easy to identify on CT scans and should be avoided (Fig. 20.3). The transabdominal approach is suitable for lesions anterior or lateral to the bladder and is commonly used for biopsy of lymph nodes along the common iliac vessels, lesions that are located anterior or lateral to the psoas muscles, lower mesenteric masses, and, occasionally, anterior external iliac nodes.

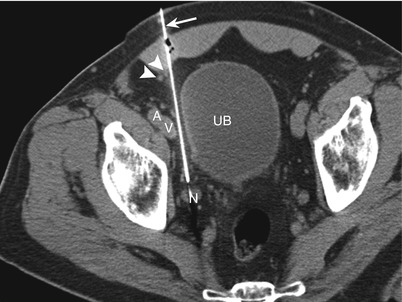

Fig. 20.3

Anterior abdominal approach. A computed tomographic scan shows the biopsy needle (arrow) advanced between the urinary bladder (UB) and the external iliac vessels (A and V) to biopsy a small internal iliac node (N). Note the presence of inferior epigastric vessels (arrowheads) immediately lateral to the needle trajectory

Deep pelvic lesions are often difficult to reach by the transabdominal approach because of the intervening bowel and bladder, as well as the uterus and adnexa in female patients. A custom-tailored, curved 22-gauge needle advanced coaxially through a straight guide needle can be used to circumvent intervening structures [1, 11]. The tip of the needle is grasped with a hemostat and bent to impart a curve. Occasionally, emptying the urinary bladder may allow access to deep lesions. CTF can also be used to assist percutaneous biopsy of masses with difficult or narrow access routes, especially lesions that are intermittently surrounded by bowel loops [12]. Angling of the CT gantry is another technique that can be used to help the radiologist avoid intervening structures in CT-guided biopsies of the abdomen [13].

Bowl loops occupy a major portion of the upper pelvis. Although transgression of bowel loops with a thin 22-gauge needle is generally considered safe, an attempt should be made to avoid transgression of the bowel loops. Bowel loops may change position and shape during the course of the biopsy, and bowel peristalsis may deflect the needle from its projected path. Hence, CT scans should be obtained between incremental needle advancements in order to determine the exact location of the needle with respect to the bowel loops (Fig. 20.4). Placing the patient in a lateral decubitus position may help displace the bowel loops from the projected needle path [1]. Alternatively, administration of saline through the guide needle can be used to displace intervening bowel loop and allow safe access to an otherwise unreachable lesion (Fig. 20.5).

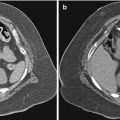

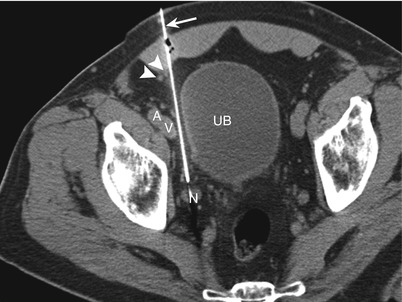

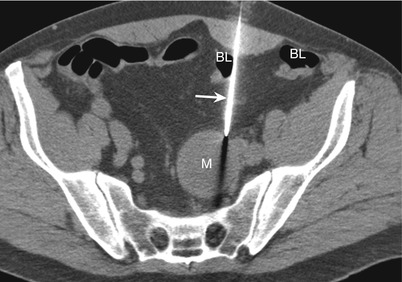

Fig. 20.4

Anterior abdominal approach. A computed tomographic scan shows an 18-gauge needle (arrow) advanced between the bowel loops (BL) to sample a presacral lesion (M)

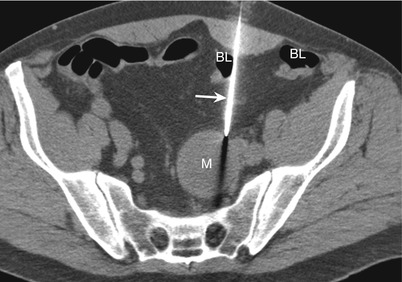

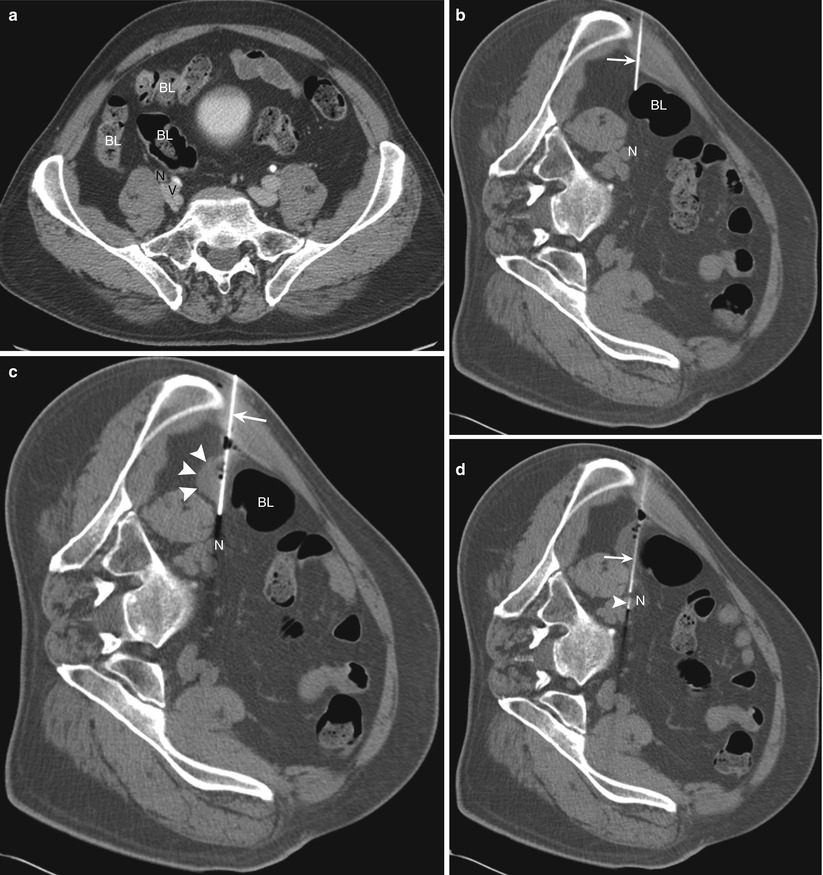

Fig. 20.5

Lateral abdominal approach. (a) A computed tomographic scan of the patient in the supine position shows bowel loops (BL) anterior to a common iliac node (N), which is located anterolaterally to the common iliac vessels (V). (b) Placing the patient in the left lateral decubitus position created a small window lateral to the bowel loop (BL) allowing initial needle (arrow) insertion. However, further advancement of the needle is not possible because of the presence of bowel. (c) Injection of saline (arrowheads) through the 18-gauge Hawkins needle (arrow) resulted in displacement of the bowel (BL), allowing safe advancement of the needle up to the target node (N). (d) A 22-gauge needle (arrowhead) was advanced through the Hawkins needle (arrow) to sample the node (N)

With the transabdominal approach, the potential risk of inadvertent transgression of bowel loops limits the size of biopsy needle that can be used, precluding the option of obtaining a core specimen in most patients. This approach can also be painful for the patient because of the peritoneal transgression. The presence of abdominal wounds, dressings, or colostomy bags may preclude access in patients who have just had surgery.

Transgluteal Approach

For the transgluteal approach, the patient is usually placed in a prone, prone oblique, or lateral decubitus position. This approach is also called the trans-sciatic approach because the needle traverses the greater sciatic foramen. Care should be taken to avoid the neurovascular structures (branches of internal iliac arteries and sciatic nerve) coursing in the sciatic foramen. The needle should be inserted through the sacrospinous ligament in the caudal part of the notch below the level of the piriformis muscle to avoid injury to the gluteal vessels and the sacral plexus, which lie anterior to the muscle. It is generally recommended that the needle be placed close to the edge of the sacrum to avoid injury to the sciatic nerve and gluteal vessels that exit the pelvis in the anterior portion of the notch, close to the ischium [3, 6, 7].

The transgluteal approach is generally used for posterior pelvic lesions in the lower part of the pelvis at the level of the greater sciatic foramen that are difficult to access by an anterior approach because of the intervening bowel, bladder, uterus, and iliac vessels (Fig. 20.6). Lesions located in the presacral and perirectal regions, lesions located posterior or posterolateral to the urinary bladder (Fig. 20.7), and adnexal masses can be accessed with this technique.

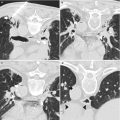

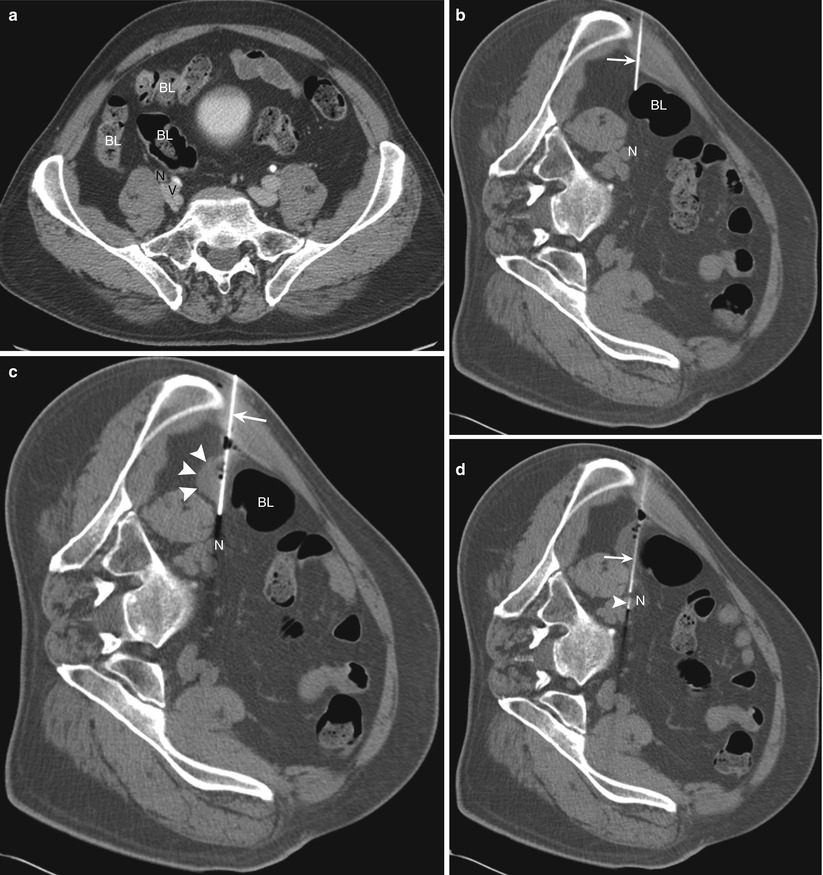

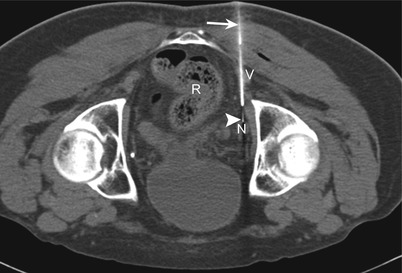

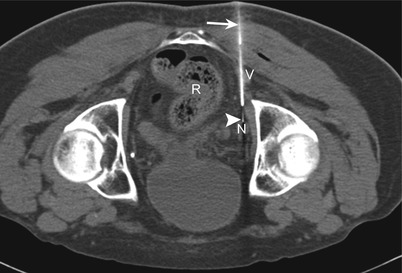

Fig. 20.6

Transgluteal approach. A computed tomographic scan shows the coaxial technique, with a 22-gauge inner needle (arrowhead) advanced through an 18-gauge guide needle (arrow) to biopsy an obturator lymph node (N). The needle is passing through the sacrospinous ligament and between the rectum (R) and vessels (V)

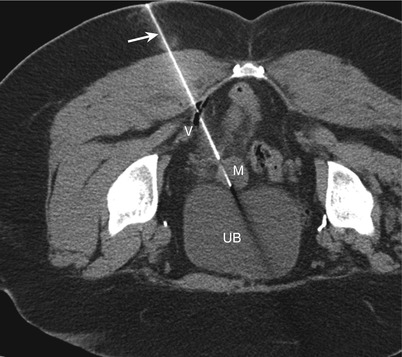

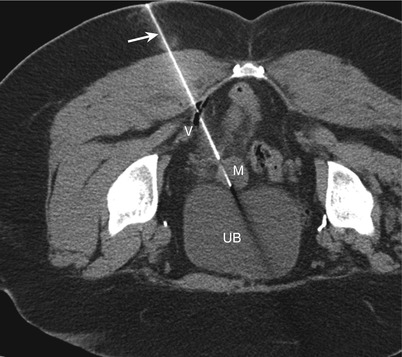

Fig. 20.7

Transgluteal approach. A computed tomographic scan shows the needle (arrow) passing through the sacrospinous ligament, posterior to the inferior gluteal vessels (V), for biopsy of a soft tissue mass (M) located posterior to the urinary bladder (UB)

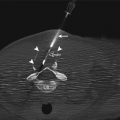

Cranial needle angulation allows the transgluteal approach to be used for accessing upper pelvic lesions located cranial to the level of the greater sciatic foramen. Using a triangulation method, the physician estimates the needle angle from contiguous axial CT scans obtained from the level of the planned skin entry site to the level of the target lesion. The needle is inserted below the level of the lesion and advanced cranially and medially through the greater sciatic foramen, and axial CT scans are obtained to check the needle tip position and angulation (Fig. 20.8).