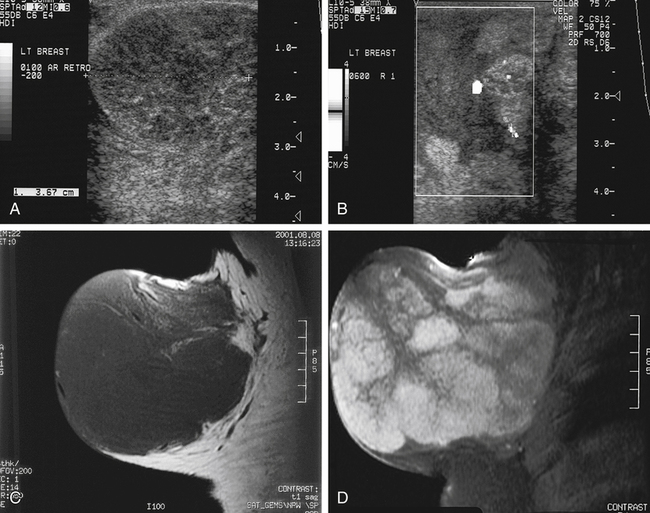

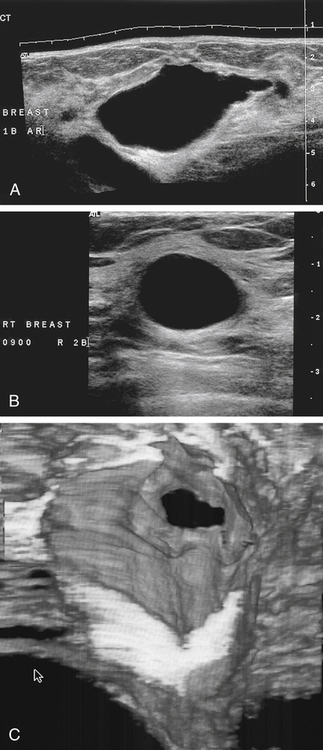

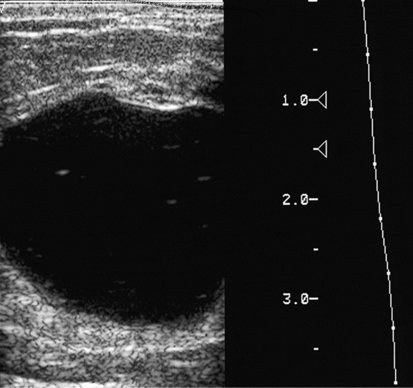

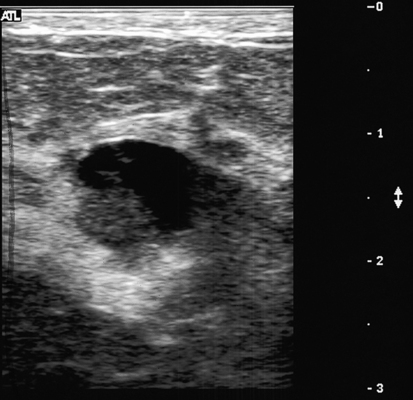

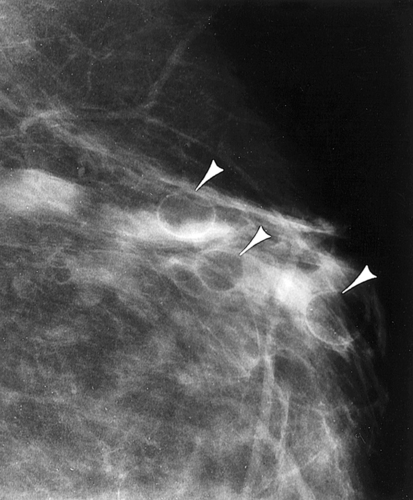

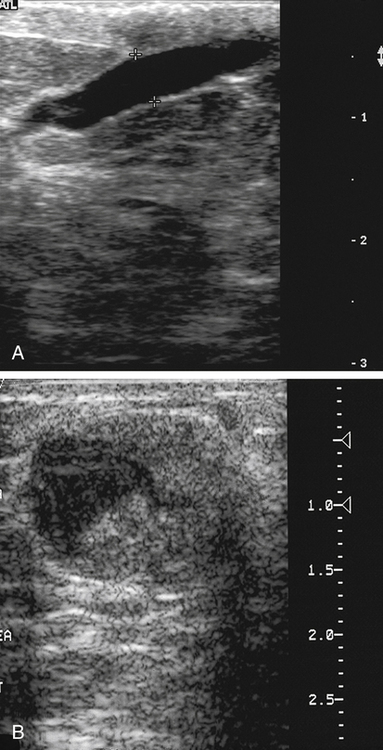

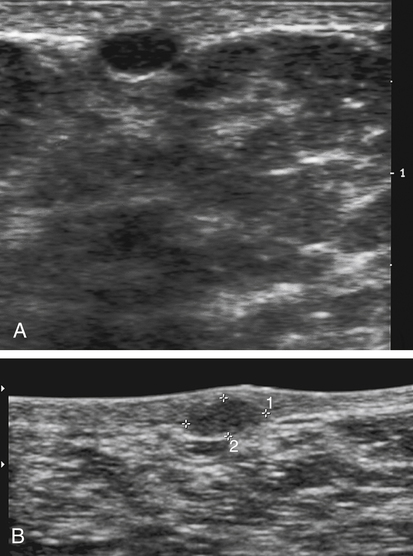

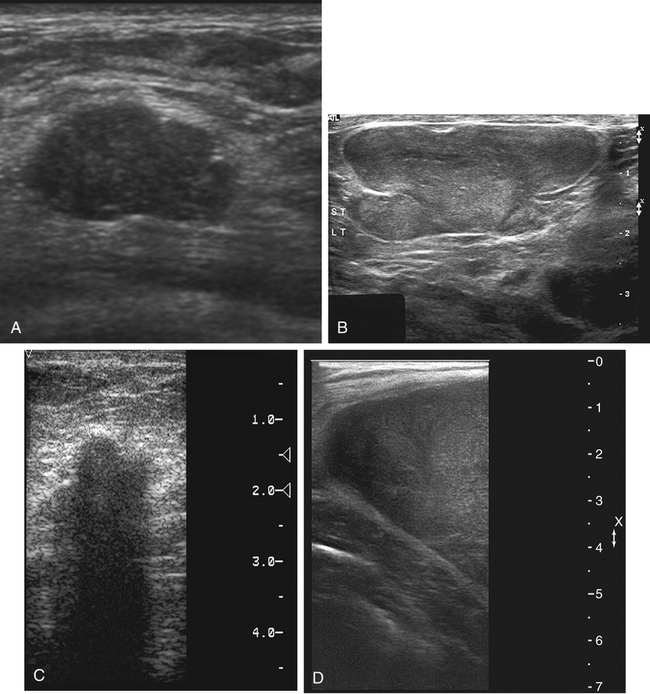

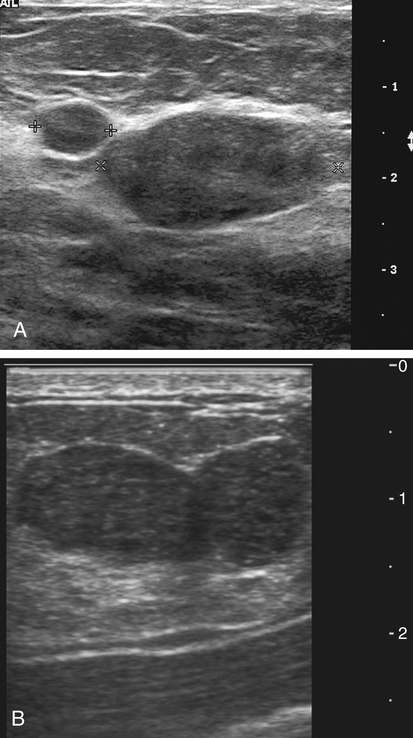

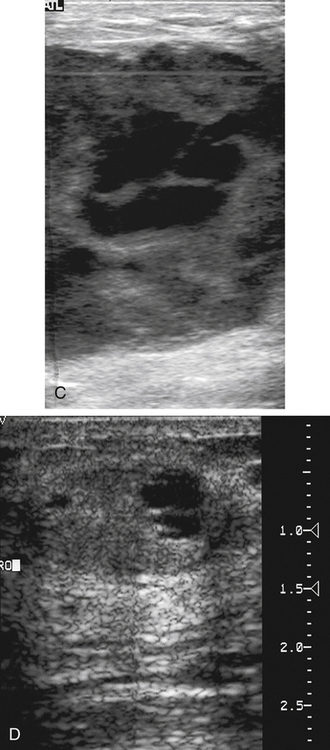

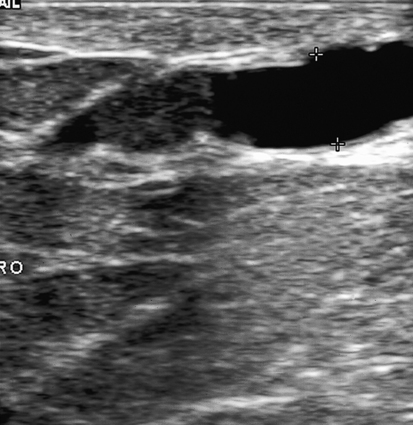

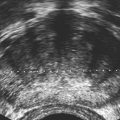

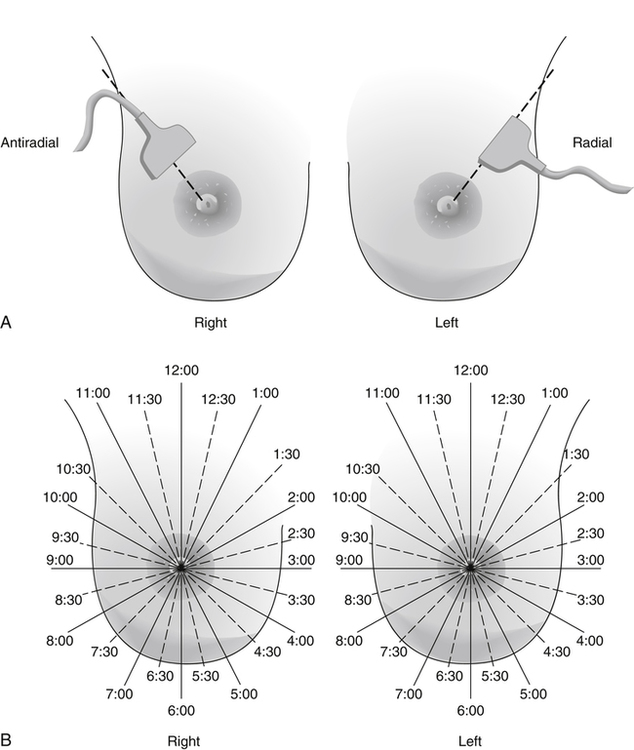

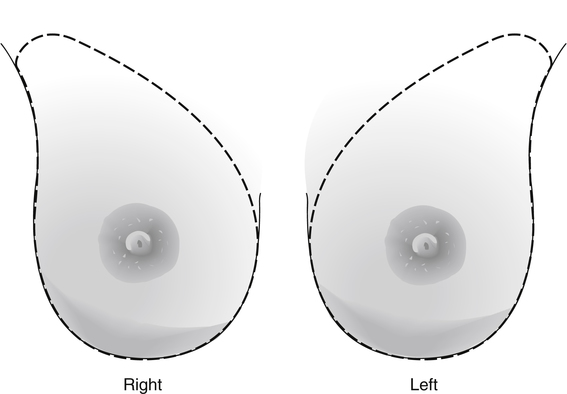

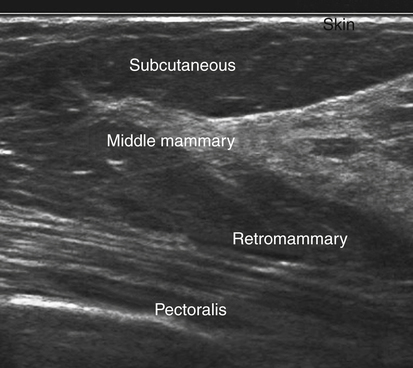

Dana Salmons and Charlotte Henningsen • Describe the sonographic appearance of common cystic masses of the breast. • Describe the sonographic appearance of common benign neoplasms of the breast. • Describe the sonographic appearance of common malignant neoplasms of the breast. • Describe the sonographic appearance of an augmented breast. • Describe the sonographic appearance of an inflamed breast. • Describe the sonographic appearance of an injured or postsurgical breast. The preferred method for breast sonography uses radial and antiradial planes (Fig. 27-2, A). Multiple ducts start at the nipple and radiate out toward the periphery of the breast parenchyma. With radial and antiradial scanning, ductal involvement of a mass is more readily seen. Turning on the lesion is important so that all aspects of the lesion are evaluated. The preferred method of annotation uses a quasigrid pattern. First, the breasts are viewed as a clock face. Directly above the nipple on either breast is 12:00. Right medial breast and left lateral breast are 3:00. Directly below the nipple bilaterally is 6:00. Right lateral breast and left medial breast are 9:00 (Fig. 27-2, B). Next, the distance the image is taken from the nipple is documented in centimeters from nipple (CMFN). The pathology in Fig. 27-2, C, would be labeled as follows: RT BREAST, 5:00 1 CMFN rad (radial) or arad (antiradial); LT BREAST, 1:00 4 CMFN rad or arad. A craniocaudal (CC) mammogram is used to discover whether a mass is in the medial or lateral portion of the breast. A CC mammogram is acquired with placement of the film inferior to the breast, and the radiograph beam is directed superiorly to inferiorly (Fig. 27-2, D). The CC marker is placed just outside the lateral breast border. If the mass is located between the nipple and the CC marker, the mass is in the lateral portion of the breast. If the mass is located between the nipple and the contralateral side of the CC marker, the mass is medial. Superior and inferior mass location is determined with a mediolateral oblique (MLO) mammogram. A MLO mammogram is acquired with placement of the film at an oblique angle that is lateral and slightly inferior to the breast. The radiograph beam is directed mediolaterally at the same obliquity as the film (see Fig. 27-2, D). Because this is not a true mediolateral image, masses on the lateral breast are slightly lower than masses that appear in the image. Masses in the medial breast are slightly higher. Normal human breasts are two modified sweat glands on the upper anterior portion of the chest, lying anterior to the pectoralis major. The areola and nipple are centrally located on each breast. Each adult female breast has a conic formation with a “tail” that extends toward the associated axilla (Fig. 27-3). The function is to produce and release milk during reproduction. The breasts are composed of fatty, glandular, and fibrous connective tissues, all with differing echogenicities. Proportions of these tissues vary from patient to patient and can vary within the breast of the same patient. The normal sonographic appearance is quite variable. The normal skin thickness overlying the breast is less than 2mm. Beneath the skin are three layers of mammary tissue. Starting superficially, the subcutaneous layer located just under the skin is mainly fat and, in the breast, is sonographically hypoechoic. The middle mammary layer contains the ducts, glands, and stroma of the breast and is relatively echogenic. The deep retromammary layer is also composed of hypoechoic fat and is the portion of the breast that lies superficial to the pectoralis major. Traversing through these layers are hyperechoic Cooper’s ligaments (Fig. 27-4). A simple cyst must have certain sonographic qualities to be considered simple. The mnemonic STAR may assist in identification of a simple cyst. (Fig. 27-5, A and B). A simple cyst should be: S, smooth and thin-walled; T, through transmit; A, anechoic; and R, round or oval. Interior echoes within a cyst can be the result of improper gain or power settings or anterior reverberation artifact, or they may be real and considered complex. Newer ultrasound machines are better at depicting debris within cysts. This debris may be seen and yet not be considered worrisome for malignant disease. In these cases, some radiologists use the term “benign-appearing” instead of “simple-appearing” cyst (Fig. 27-6). During pregnancy or lactation, a milky cyst may form from an obstruction of the lactiferous ducts. Galactoceles are considered rare, but when galactoceles are present, patients usually have periareolar palpable masses. As expected, ductal ectasia may be present (Fig. 27-9, A). Abnormalities associated with galactoceles are mastitis and abscess. Galactoceles appear as well-marginated, round or oval masses. They typically contain echoes from fatty, milky material and can demonstrate fat-fluid levels. They resolve to oil cysts because of their composition and usually change from a complex cyst to one with a more anechoic appearance. Limited through transmission may be visualized. Doppler evaluation should be negative for internal blood flow (Fig. 27-9, B). Fibroadenoma is the most common benign mass in premenopausal women and is more common in black women. About 50% of all breast biopsies result in a fibroadenoma tissue diagnosis. Fibroadenomas are stimulated by estrogen and are frequently identified in women of reproductive age, usually women younger than 30 years.1 Because they are hormonally stimulated, they can grow rapidly in pregnant women. New fibroadenomas rarely are found in postmenopausal women with or without hormone replacement therapy. These masses, as with any new solid mass in a postmenopausal woman, should be considered highly suspicious for cancer, and tissue diagnosis is essential. Clinically, the patient usually has a firm, rubbery, mobile mass when palpable. Fibroadenomas are found more frequently in the upper outer breast quadrants. Bilateral and multiple masses are found in 10% of cases.2 If small and proven to be a fibroadenoma via core biopsy, these masses may be left within the breast and followed with serial sonograms. When fibroadenomas are large, surgical removal is usually recommended. Fibroadenoma variants consist of giant fibroadenomas and juvenile fibroadenomas. There is no standard measurement a fibroadenoma must reach before it is considered giant, but the term is usually reserved for fibroadenomas measuring 6 to 8cm or greater. Fibroadenomas are smooth or macrolobulated masses that have a wide rather than tall formation. They usually measure less than 3cm. These lesions displace rather than infiltrate surrounding tissue, making them well-marginated masses. They are typically homogeneous with low-level internal echoes but can show areas of cystic necrosis if they outgrow their blood supply. Through transmission may or may not be seen (Fig. 27-11, A and B). Peripheral vascularity may be visualized with Doppler. “Popcorn” calcifications can form; sonographically, these masses may completely attenuate the ultrasound beam, producing significant posterior shadowing. A sonogram may not be helpful in these cases (Fig. 27-11, C). Cystosarcoma phylloides are also called phylloides tumors, proliferative fibroadenomas, or periductal stromal tumors. The peak age for cystosarcoma phylloides is 30 to 40 years, roughly 10 years after the peak age for fibroadenomas. Cystosarcoma phylloides are rare but when seen are usually unilateral. Approximately 10% of cystosarcoma phylloides are malignant and have the potential for metastases, usually to the lung.3 Malignant phylloides tumors tend to grow faster and larger than benign phylloides tumors. Sonography cannot differentiate between benign phylloides tumors, malignant phylloides tumors, or fibroadenomas. Unless some ductal ectasia is seen, intraductal papilloma is difficult to show and may result in a negative sonogram. Radial scanning to elongate ducts is essential. When visible, intraductal papilloma demonstrates a solid mass or solid tissue mural nodule within a duct or cyst. The nodule may be round, oval, or tubular following the contour of the duct or cyst (see also the description of papillary carcinoma) (Fig. 27-13).

Breast Mass

Breast

Sonography Scanning Planes

Breast Sonography Annotation

Location of a Mass with Mammographic Images

Normal Sonographic Anatomy

Cystic Masses

Simple Cyst

Sonographic Findings

Galactocele

Sonographic Findings

Benign Neoplasms

Fibroadenoma

Sonographic Findings

Cystosarcoma Phylloides

Intraductal Papilloma

Sonographic Findings

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Breast Mass