As part of a current and continuing national trend to develop centers for neuroscience care, radiosurgery programs are and will be a “hot” topic for the next several years. Radiosurgery is also an important component of neurological surgery residency training. The Residency Review Committee (RRC) for neurological surgery has expanded the specialty definition of neurological surgery to include treatment of diseases of the brain and spinal cord and their coverings and blood supply with stereotactic radiosurgery. This expanded definition presupposes that neurosurgeons receive clinical and didactic training in radiosurgery during residency training. Currently, the RRC requires neurosurgery residents to complete and participate in a minimum of ten adult cranial radiosurgery cases [13].

Concerns have been raised about potential market saturation as new programs are built, which can limit individual program patient volumes [11]. Despite these concerns, the role of stereotactic radiosurgery as a tool to treat diseases of the nervous system is quite high and should remain so for the foreseeable future.

Radiosurgery in Residency Training

As mentioned above, exposure to radiosurgery is an integral part of residency training. The Residency Review Committee does not specify how that training should be accomplished, leaving those details to each individual program.

Each training program tends to tailor the radiosurgery experience for its residents to the unique circumstances of the program. Didactic education may come in the form of lectures, either as part of curriculum conference or as Grand Rounds. Individualized reading will also likely be required. Textbooks, such as this one, are an excellent source to expand one’s breadth of knowledge. Recently, Kondziolka detailed the 100 most cited radiosurgery papers written; a number of these form the foundation of the principles of stereotactic radiosurgery outlined in texts, including indications, outcome, dose consideration, and complications [14]. Reading the source literature, while perhaps more labor intensive, can help crystallize one’s thinking about the information offered. Recently, the University of Florida posted an online computer module that was made available to all training programs to enhance didactic radiosurgery education [15]. Knowledge of the various radiosurgery systems in use is helpful, as one does not always know what device will be available in one’s practice setting.

Radiosurgical experience in the form of surgical cases is paramount to incorporating stereotactic radiosurgery one’s clinical practice. Although the RRC for neurologic surgery did mandate that each resident participate in a minimum of ten radiosurgery cases before the completion of residency training [13], mechanisms by which the resident will obtain that case experience is not so certain. Almost always, radiosurgery cases are performed as outpatient procedures and frequently off-site from the hospital in which the residents rotate. To solve this problem, some programs, including Johns Hopkins, University of Pittsburg, and University of Missouri-Columbia, have established elective or selective rotations to ensure that residents receive adequate exposure. At Johns Hopkins, for example, a 4-month block during the PGY-4 year is devoted to functional and stereotactic radiosurgery. In other programs, the resident may need to make some additional effort to be able to participate; understanding that minimum case numbers are required for residency completion may provide the necessary impetus.

Practice Development

Decision to Proceed

The first step in developing a radiosurgery practice is making the decision to include radiosurgery in one’s personal procedural offerings to patients. Not all neurosurgeons perform all procedures. Even neurosurgeons in general practice have the option to chose the types of cases they wish to do and refer other cases to other neurosurgeons, either within the same group, to another group, to local academic center, or to a distant academic center.

If one is in an academic neurosurgical practice or a large group private practice, individuals in the group may have subspecialty interests. Sometimes, a neurosurgeon can specialize in radiosurgery only. Colleagues within the group, neurosurgeons and radiation oncologists who do not do radiosurgery, and other physicians will refer potential cases to that particular individual for evaluation and treatment. In other instances, a neurosurgeon may have subspecialty interests for which radiosurgery can be a treatment option for patients. Given the current indications for radiosurgery, such subspecialties include neuro-oncology, functional neurosurgery (pain or movement disorders), epilepsy surgery, and cerebrovascular surgery. Neurosurgeons focused on these subspecialties may also chose to treat patients with other “non-subspecialty” disease processes with radiosurgery; while the targets and doses may be different, many of the technical principles are similar.

A general neurosurgeon in private practice or academic practice may also include radiosurgery as part of his/her clinical offerings. Clinical volume may be, but is not necessarily less than in the previous circumstances, depending on one’s local environment. For instance, in a medical community with a 500,000 catchment area, if four neurosurgeons are each offering radiosurgery, one’s case volume may be less than five cases per year; the neurosurgeon may decide that for that volume, she/he would rather refer appropriate radiosurgery cases to another colleague.

The neurosurgeon should consider a number of factors in making the decision of whether or not to include radiosurgery as part of one’s practice. Perhaps the first factor is “what is the potential volume of patients available to treat?” By extrapolating data of potential case volume and population, perhaps one radiosurgery case could be performed for every 4,000 people each year. Volume, however, is not usually this high. One needs to assess the extent of out-migration from his/her catchment area and how many other practitioners are doing radiosurgery locally, as referral patterns may be difficult to break. Another factor is the proximity of radiosurgery facilities to one’s office or hospital(s). Many planning systems can permit remote planning, which makes distance less of an issue; in contrast, travel time is not usually being used for other productivity. The expectations of one’s employer may be an issue. A hospital-employed neurosurgeon or one joining an existing group (academic or private practice) may be expected to include radiosurgery to meet service needs. The type of radiosurgery system(s) available is also important to consider. The device may not be the same as used during residency or other practice venues, and purchase of a familiar device or system is not practical for an individual and unlikely for an institution unless its present system is ready for upgrade or replacement. Therefore, a neurosurgeon may need to obtain additional training in anticipation of including radiosurgery in practice. A vendor-sponsored course or a trip to a center with the particular radiosurgery platform can go a long way to increasing comfort with the existing system.

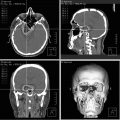

Current and potential future levels of reimbursement are also an issue. The National Health Care Advisory Board had suggested a potential decrease in reimbursement in 2008 [10]. Figure 66.1 shows the change in total radiosurgery reimbursement per case by Medicare between 2007 and 2008. Table 66.2 illustrates the changes in physician billing per case at the University of Missouri from 2008 to 2012, which shows the dynamic change in the billing for radiosurgery. Over the span of one year the RVU for radiosurgery dropped by seven units resulting in a significant decrease in reimbursement. However, over the following years, the total charges and RVUs have steadily increased. In addition, more CPT codes were added to allow for better characterization of the treatments being performed. Although there has been an overall decrease in the reimbursement of stereotactic radiosurgery, the earning potential may be equivalent due to the unbundling of the CPT codes. The future of radiosurgery reimbursement is difficult to predict, but the reality of the situation is that it will depend heavily on the political and socioeconomic condition of the country and its effects on the health-care system at large.

Fig. 66.1

Changes in CMS reimbursement for outpatient SRS by Medicare over 1 year. From: Innovations Center, Health Care Advisory Board. Future of Neurosciences; Strategic Forecast and Investment Blueprint. The Advisory Board Company 2008; used with permission

Table 66.2

Changes in physician charges and RVUs at a single institution for various CPT codes

Time spent on radiosurgery means time not spent on other types of cases. Compensation for these other cases may exceed reimbursement from radiosurgery; therefore, personal economics also enters the equation.

One should also keep in mind that radiosurgery is just one of several options for treating particular disorders. A physician’s selection of radiosurgery versus open surgery for a procedure depends on the individual situation and patient, as one method may be preferred or superior to the other for various reasons. However, offering radiosurgery increases the scope of one’s practice, thereby increasing procedure volume and thus profits. For example, some patients have absolutely no interest in an open operation if a minimally invasive option is available, even if open surgery has some clear advantages. By offering radiosurgery, one’s practice volume can benefit from those patients who may otherwise choose to leave the area to receive radiosurgery elsewhere when it is not locally available. Lastly, as indications for radiosurgery change, additional patient volumes may accrue. Two examples are worth mentioning. A patient with multiple brain metastases, one of which is very large and symptomatic, may be a candidate for radiosurgery for the smaller lesions after surgical resection of the large one. In another case, a patient with a single metastasis may be a candidate for radiosurgery to the postoperative tumor bed instead of whole-brain radiotherapy. In both circumstances, being able to provide radiosurgery generates additional case volume to the neurosurgeon that, in the absence of radiosurgery capabilities, would not have been available.

Becoming Credentialed

Institutions and patients both want to be certain that physicians who care for patients are qualified to do so. Radiosurgery is no different from any other treatment in that regard. For neurosurgeons, radiosurgery is not as technically demanding as other procedures (microvascular surgery, for instance), but it does require a significant cognitive skill set. The neurosurgeon needs to know which patients and lesions are appropriate for treatment, what structures are potentially in harm’s way during treatment of a particular patient, what is an appropriate target volume, etc. Knowledge of radiation dosimetry is helpful when interfacing with the radiation oncologist, who must frequently incorporate past radiation treatments into a radiosurgery prescription to achieve an effective dose without undue long-term sequela. Therefore, neurosurgeons who provide radiosurgery need to be credentialed. Such credentialing is particularly important if the radiosurgery center is open to multiple physicians from outside the hospital/clinic in order for the center to maintain quality control.

A few credentialing protocols have been described for neurosurgeons [16, 17]. Some centers may incorporate all, a portion, or none of these protocols. Completing the requirements for credentialing is usually not particularly arduous, but should be anticipated. Most credentialing requirements will probably include at least some of following features:

Neurosurgeons should complete a radiosurgery course, ideally sponsored by the vendor of the software/hardware being used at the Center. The course should include simulated cases. Most vendors provide such a course for physicians as part of the purchase of their devices. The neurosurgeon may need to pay for the course; such costs can be negotiated as part of the contractual process for hospital or group-employed neurosurgeons.

Neurosurgeons should have experience in stereotactic surgery. Such experience demonstrates competence and understanding of volumetric localization of targets in three-dimensional space and insures that Halo ring immobilization, which many systems require, will be well accomplished. Cases providing such experience, in addition to radiosurgery, include deep brain stimulation and stereotactic brain biopsy.

The neurosurgeon should perform a number of radiosurgery cases under the direct supervision of an experienced neuro/radiosurgeon. This supervised experience may occur during residency training or as an attending neurosurgeon.

Documentation of the experience is important as well. Case number may vary. Cleveland Clinic specified that either the neurosurgeon or radiation oncologist involved in a case has residency experience of 50–100 cases or attending experience of 25–50 cases [17]. Initial supervision by a senior colleague may also be necessary [16].

Building a Referral Base

Once a neurosurgeon decides to perform radiosurgery, she/he should identify potential referring physicians. These physicians may be from within one’s hospital community or from the surrounding area. Again, consideration of the indications for radiosurgery can help identify to which physicians the neurosurgeon should reach out to explain the available services.

One key group of potential referring physicians should be radiation oncologists. Radiation oncology collaborates with neurosurgery for patient treatment in most centers. The radiation oncologist is usually responsible for the radiation dose, as well as supervising the physics personnel involved with developing the treatment plan. Radiation oncology is often, but not always, the responsible party for upkeep and quality assurance of the devices used to generate and deliver the ionizing radiation. In some centers, a single radiation oncologist may have radiosurgery responsibilities; in others, those duties may be shared. Identification and dialogue with radiation oncologists outside the locale or who would not be participating in radiosurgery procedures is also helpful. Discussion with these radiation oncologists is appropriate to define groups of patients for to treat with radiosurgery. Updating them on evolving radiosurgery indications, such as radiosurgery to multiple lesions, radiosurgery to the tumor bed after resection, fractionated radiosurgery for large lesions, and radiosurgery for spinal lesions, is appropriate [18–21]. Sharing references can be helpful, as some indications represent a paradigm shift for radiation oncology, as well as for neurosurgery.

Although medical oncologists do not directly participate in stereotactic radiosurgery treatment, their participation as referring physicians is essential, since patients with metastatic carcinoma represent the largest group of patients to treat. Better patient referral can be expected when the medical oncologists understand the issues related to stereotactic radiosurgery treatment.

While radiation oncologists and medical oncologists will likely account for the majority of referrals, other physicians should not be discounted. Endocrinologists should become aware of the potential for radiosurgery to treat pituitary tumors refractory to surgical resection. Otolaryngologists often refer patients with vestibular schwannomas. Neurologists may be a source of patients with trigeminal neuralgia, epilepsy, movement disorders, or arteriovenous malformations. Dentists and oral surgeons may also refer patients with trigeminal neuralgia [11]. Because pediatric patients can account for 10–15 % of patients in some centers [22], pediatricians and pediatric oncologists are also a potential source of referrals that can be cultivated.

Marketing to the Community

Success in building a radiosurgery program can be related to marketing to the medical community as well as to patients. Potential referral sources as described above need to know that radiosurgery expertise is available. Helpful information includes a list of the clinical indications for radiosurgery, inclusion and exclusion criteria, the sequence of events involved in treatment of a patient, and how to refer patients for treatment. A variety of means of communicating this information are available. Presentations at medical staff meetings, mailed brochures or letters, Grand Rounds presentations, and conferences are all useful for marketing purposes, particularly since they also provide appropriate education about radiosurgery. The Internet has also increased physician and patient access to information about radiosurgery. Additionally, direct phone calls from physicians performing radiosurgery to referring physicians can be very effective. Finally, promptly communicating back to referring physicians after assessing patients enhances the process.

Marketing to patients directly is also important. Because patients are using the Internet more often as their source of medical information, physicians who do not utilize Web sites are at a distinct disadvantage as patients look for options for treatment of their ailments. Therefore, information on a Web site should be written at a level that patients can comprehend. For example, reduction or simplification of medical vocabulary is helpful to make the information more understandable. Television and radio spots, although more expensive, can also be used to enhance one’s marketing to patients.

The physician can augment marketing also by partnering with the institution housing the radiosurgery center. Two different strategies for marketing are available [11]. In the first, marketing revolves around the radiation delivery device as the key point of focus. The institution’s advertisements indicate that it has the capability of treating patients with a Gamma Knife, a Cyberknife, a Trilogy, or any other delivery system that has been purchased for the program. This type of product marketing appeals to patients by name-recognition of a particular device. An alternative strategy focuses on the particular disease process—like trigeminal neuralgia, or AVMs, or brain tumors—and notifies the public that a noninvasive treatment modality is available for that disease. Both strategies, especially if used together, can be very effective.

Even though marketing is important to increase physician and patient awareness about radiosurgery as a tool to treat diseases, it is important to avoid exaggeration and misrepresentation in information provided, particularly on the Internet, where there are no truth-in-advertising regulations, and where “data” can be promulgated directly to patients without scientific peer review [23]. Brada and Cruickshank [24] raised such concerns in an editorial in the British Medical Journal. Unfortunately, these concerns were lost in the authors’ own misrepresentations [25–28]. As centers and physicians market their expertise and capabilities, they must provide accurate information to maintain their credibility.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree