Jean Noel Buy1 and Michel Ghossain2

(1)

Service Radiologie, Hopital Hotel-Dieu, Paris, France

(2)

Department of Radiology, Hotel Dieu de France, Beirut, Lebanon

28.1.1 Clinical findings []

28.2 Adenocarcinoma

28.2.1 Clinical Findings []

28.2.2 Pathology

28.2.3 MR Findings []

28.3.1 Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma

28.3.2 Small Oat Cell Carcinoma

28.6 Miscellaneous

28.6.1 Lymphoma

28.6.2 Leukemia

28.6.3 PNET

28.7 Secondary Tumors []

Abstract

The most common two types are:

Carcinoma of the cervix accounts for almost all the malignant tumors of the cervix, with roughly 75–80 % of squamous cell carcinomas and 20–25 % of adenocarcinomas. Other malignant epithelial tumors, mixed epithelial and mesenchymal tumors, mesenchymal tumors, very uncommon miscellaneous tumors and secondary tumors are quite uncommon.

Detection of carcinoma of the cerix is usually made in asymptomatic women on a routine cervical smear or is revealed by clinical findings among the most common one is vaginal bleeding. Vaginal touch and examination with the speculcum can unfortunaly in some cases identify a tumor at a stage already advanced. Colposcopy is essential to visualize small lesions and to guide the biopsy which confirms the carcinoma of the cervix. Imaging modalities in the great majority of cases have no place at all in the detection and in the diagnosis of cervical carcinoma. However they play an important role in the evaluation of the extension of the tumor before surgery or after a neoadjuvant chemotherapy has been performed, and in the followup of the patients in the detection and characterization of recurrences.

28.1 Squamous Cell Carcinoma

28.1.1 Clinical findings [1]

a)

Microinvasive squamous cell carcinoma (MICA)

MICA is considered as preclinical stage in the progressive spectrum of squamous intraepithelial lesion (SIL) and frank invasive carcinoma of the cervix uteri.

Definition of MICA:

A tumor that invades to a depth of not more than 5 mm taken from the base of the epithelium, either surface or glandular, from which it originates and a second dimension, the horizontal spread, must not exceed 7 mm according to the FIGO classification [6].

Clinical features:

The majority of MICA occurs in women 35–46 years of age. Most patients are asymptomatic and the tumors are generally discovered on a routine cervical smear. The cervix demostrates a grossly normal appearance or non specific findings, such as chronic cervicitis or true erosion. Colposcopically, detection of MICA requires invasion of more than 1 mm into the cervical stroma. Areas of MICA usually display dense acetowhitening consistent with high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (SIL). Many colposcopists routinely treat all large biopsy-confirmed, high grade SIL using excisional methods such as loop excision. However a diagnosis of MICA should only be made after a conization has been performed to exclude more advanced disease.

b)

Invasive squamous cell carcinoma

There is a considerable body of evidence that invasive squamous cell carcinoma develops from SIL, and consequently, women with invasive squamous cell carcinoma have similar epidemiologic characteristics. Like women with SIL, women with invasive squamous carcinoma began heterosexual activity early in life, married early, are multiparous, and have many sexual partners. These associations suggest a role for a sexually transmitted agent in the etiology of cervical cancer. Multiple types of human papillomavirus (HPV) are resposible for the development of cervical carcinoma, predominantly HPV 16, 18, 45 and 58.

The average age of patients is 51 years (a little older than patients with high-grade SIL or with MICA). Women under the age of 35 years account for 22 % of all patients. The most common and significant feature is bleeding following intercourse or douching. Intermittent spotting, serosanguinous discharge, and frank hemorrhage are also common. Malodorous discharge and pain, often radiating to the sacral region occurs in 10–20 % of patients. Means for accurate detection and diagnosis of frank invasive carcinoma include cytology, colposcopy, and colpospically directed punch biopsy.

28.1.1.1 Pathology

28.1.1.2 Macroscopy [1]

Early Lesions

Ninety-eight percent are localized in the transformation zone, with variable degrees of encroachment onto the neighboring native squamous epithelium.

They may be focally indurated or ulcerated or may present as a slightly elevated and granular area.

Advanced Tumors

More advanced tumors have two major types of gross appearance.

(a)

Endophytic:

Are ulcerated or nodular.

Tend to develop within the endocervical canal.

This pattern frequently invades deeply into the cervical stroma to produce a large barrel-shaped cervix.

In some patients, the cervix appears normal.

(b)

Exophytic:

Have a polypoid or papillary appearance

28.1.1.3 Microscopy and Grading

The tumor may be in situ, microinvasive, or invasive.

Grading is reported in Table 28.1.

Grade 1 |

– Cells mature with irregular large nuclei and abundant cytoplasm |

– Keratin pearls: concentric whorls of abundant keratin in the centers of neoplastic epithelial nests |

– Stroma infiltrated by chronic inflammatory cells |

Grade 2 |

– Neoplastic cells are more pleomorphic with large irregular nuclei and scanty cytoplasm |

– Cell borders are indistinct |

– Keratin pearls are nonexistent |

Grade 3 |

– Neoplastic cells show hyperchromatic oval nuclei with scant indistinct cytoplasm |

– Clear-cut squamous differentiation manifested by keratinization may be difficult to find |

Variants of Squamous Cell Carcinomas

1.

Verrucous carcinoma

At microscopy, they are characterized by frond-like papillae without the central fibroconnective tissue.

2.

Warty carcinoma

Unlike verrucous carcinoma, warty carcinomas demonstrate features of a typical squamous cell carcinoma at the deep margin. Many of the malignant cells have cytoplasmic vacuolization and nuclear changes closely resembling koilocytotic atypia.

3.

Papillary squamous cell carcinoma

They are composed of papillary projections that are covered by several layers of atypical epithelial cells.

4.

Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma

28.1.2 MR imaging Findings Before Treatment

28.1.2.1 Tumor

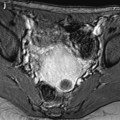

On T2, the lesion has an intermediate signal between cervical stroma and adipose tissue (Figs. 28.1, 28.2, 28.3, and 28.4).

Fig. 28.1

Squamous cell carcinoma with parametrial involvement (stage IIB). (a) Sagittal view 5.2 × 4.4 cm mass of intermediate signal occupying the entire cervix distending the cervical stroma and vagina. Differentiating distended vagina from cervical thinned stroma is not evident. (b–f) DMR before (b) and 25 (c) Fig. 28.1 (continued) (d–i) 70 (d), 125, and 240 (e) seconds after injection with time-intensity curves (f) shows that the central part of the tumor (red ROI in e) enhances less than a peripheral ring (blue ROI in e) but more than the normal cervical stroma (green ROI in e). The peripheral enhancement corresponds probably to a mixture of tumor and adjacent infiltrated stroma. (g, h) Axial T2 (g) and corresponding DMR at 240 s, (h) at low level, show disruption of right and left vaginal wall with obvious cardinal ligament invasion on the left. The anterior wall of the vagina is also disrupted on T2, but there is integrity of the bladder wall on DMR. (i, j) DWI at b1000 (i) and corresponding ADC map (j), at the level of (g), show hyperintense tumor with ADC of 0.45 × 10−3 mm2/s. Left lobulation in the cardinal ligament is well seen on both images

Fig. 28.2

Squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix in a 79-year-old woman (stage IIB). (a, b) Sagittal and axial T2W images show a 4.8-cm mass of intermediate signal intensity occupying the endocervical canal, protruding in the external and internal os. On the sagittal image, a thin band of normal hypointense cervical stroma is seen posteriorly (arrow in a), while it is almost inexistent and disrupted anteriorly. On the axial image, disruption of the stroma is well individualized in several areas with left and right invasion in the cardinal ligament (arrows in b). (c, d) DW image at b1000 (c) and corresponding ADC map (d) show the tumor to be hyperintense with an ADC of 0.9 × 10−3 mm2/s. However, invasion of the stroma is not evident Fig. 28.2 (continued) (e–i) DMR before (e) and 25 (f), 70 (g), 125 (h), and 240 (i) seconds after injection shows arterial vessels at 25 s in the mass and the peripheral invaded stroma and cardinal ligaments. On the following phases, a peripheral enhancing incomplete ring is seen that, when compared to T2WI, corresponds probably to the periphery of the main tumor. (j) Late sagittal LAVA after injection show the mass surrounded by a highly enhancing ring anteriorly and posteriorly contrary to a normal cervical stroma that enhances less than the myometrium. It is not possible to differentiate the periphery of the tumor and the adjacent invaded stroma from the thin posterior peripheral stroma that appeared preserved on sagittal T2 image. In this case, extension of the tumor was best appreciated on T2WI

Fig. 28.3

Squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix with vaginal extension. (a) Sagittal T2W image shows the tumor of intermediate signal intensity (between adipose tissue and pelvic muscle), higher than that of cervical stroma and myometrium, occupying the cervix and disrupting posteriorly the vaginal wall. (b) Axial T2W image at the level of the cervix showing the tumor and adjacent hypointense cervical stroma Fig. 28.3 (continued) (c, d) DMR at the same level as (b) at the arterial phase (c) and corresponding time-intensity curves (d) shows marked higher contrast uptake in the tumor (red ROI) compared to normal cervical stroma (green ROI). (e) Axial T2 image at a lower level shows the tumor extending through the vaginal wall and coming in contact with the rectal wall without disrupting it. (f) Axial T2W image at still lower level shows the tumor occupying the entire vaginal lumen. The vagina is left deviated and its wall partially disrupted posteriorly on the right. (g–i) DMR at the level of (f), before (g) and after contrast injection at the arterial (h), venous, and late (i) phases, shows early contrast uptake in the tumor at the arterial phase, superior to that of the vaginal wall. The uptake in the tumor is slightly heterogeneous. The vaginal wall is ill defined posteriorly on the right. On DWI b1000 (not shown), high-intensity signal was displayed in the tumor with ADC value of 0.64 × 10−3 mm2/s. The tumor was classified FIGO stage IIA. (j) Axial T2W image 5 months later, after chemoradiotherapy, shows absence of visible tumor with reappearance of the zonal anatomy and intermediate intensity areas in the surrounding adipose tissue secondary to radiotherapy. These lesions were stable on follow-up confirming their nonneoplastic nature

Fig. 28.4

Squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix with vaginal and parametrial involvement in a 55-year-old woman (FIGO stage IIB). (a) Sagittal T2W images show a mass of intermediate signal intensity (between signal intensity of adipose tissue and pelvic muscles), measuring 4.3 cm in height and 5 cm in width, eroding the outer cervix, and occupying the upper half of the vagina. The hypointense vaginal wall is clearly disrupted posteriorly (arrow). Small Nabothian cysts are present. No endocervical lesion is identified. (b) On sagittal acquisition performed after DMR, the vaginal wall that enhances more than the tumor appears disrupted posteriorly, but this finding is better evaluated on T2WI. (c, d) DMR before (c), at the arterial phase 25 (d), and on following phases demonstrates that the tumor enhances more than the cervical stroma with a peak at the arterial phase. A small hyperintense spot is seen before injection in the endocervical canal possibly related to hemorrhage. There is suspicious left cardinal ligament involvement. (e) Axial T2W images at approximately the same level as (c, d) show the tumor surrounding the posterior cervix, disrupting clearly the left vaginal wall and invading the adjacent cardinal ligament (arrow). (f) DWI at b1000, at approximately the same level as (e), shows a hyperintense tumor with an ADC of 0.54 × 10−3 mm2/s (0.7 at b500). A small lobulation is seen protruding in the left cardinal ligament and confirming its invasion (arrow). (g) T2WI at a lower level, the tumor is in contact with the rectal wall. (h) DMR image at the level of suspicious rectal involvement (arterial phase shown) shows the tumor in contact with the rectal wall but not disrupting it. (i, j) DWI at b1000 (i) and corresponding ADC map (j) at the level where the tumor is in contact with the rectum confirms that the rectal wall is well delineated especially on (j). Several iliac lymph nodes were seen on the different sequences, the lagest one on the right measuring 18 × 10 mm. The tumor was classified stage FIGO IIB and treated with chemoradiotherapy. Follow-up MR is shown in Fig. 28.8

On T1, the lesion is usually difficult to identify because its signal is close to that of stroma.

DMR may be particularly useful in the detection and characterization of tumor.

Signal intensity measurement made in ROIs includes an intratumoral plasma component, an intracellular component, and an intratumoral interstitial component.

1.

Typically, cervical carcinoma shows earlier enhancement than that of the myometrium or cervical stroma [2]:

Most often homogeneous intense in more than 70 % of the tumor area

Less commonly a ringlike peripheral enhancement with poorly enhanced central areas

2.

Rarely, poor enhancement

Tumors with ringlike enhancement and poorly enhanced tumors were significantly larger than those with homogeneous intense enhancement [2].

Vascularization, permeability, and interstitial space in cervical carcinomas are substantially greater than those of normal tissue.

At confrontation with pathology, tumors with homogeneous intense enhancement or peripheral areas in tumors with ringlike enhancement:

(a)

Display numerous and leaky capillaries (the basement membrane of the endothelium in malignant tumors is damaged or missing)

(b)

Are predominantly composed of abundant tumor cells

(c)

Have a thin connective tissue

And conversely at pharmacokinetic analysis, (a) their mean tissue-specific transport parameter k that describes the transfer of contrast medium between the plasma compartment and interstitial space and (b) the ratio of extracellular volume to intravascular volume f were respectively significantly higher and lower than those of the center of large tumor.

Diffusion

In Edwards et al. series [3], ADC values in cervical carcinoma of 757 × 10−6 mm2/s ± 110 were significantly lower than those in adjacent epithelium 1,331 × 10−6 mm2/s or cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 1,291 × 10−6 mm2/s (Figs. 28.1, 28.2, 28.3 and 28.4). From this study, a threshold of 1,100 × 10−6 mm2/s has been proposed to differentiate invasive cervical carcinoma from nontumoral epithelium. No significant difference was found between ADC of squamous cell, adenocarcinomas, and adenosquamous carcinomas [4].

Extension may be well visualized on DWI or underestimated compared to T2WI (Figs. 28.1, 28.2, and 28.4).

In patients with incompletely excised stage IA or IB1, invasive carcinoma was identified as area of ADC of less than 1,100 × 10−6 mm2/s [3]. Combination of the results obtained with T2 and ADC improves the detection and characterization of invasive cervical carcinoma [3, 5].

When patients had biopsies taken within 2 weeks prior to MR studies, granulation and healing of the cervical epithelium can give a high signal in the adjacent stroma that is indistinguishable from invasive cervical carcinoma on T2 while these lesions could better differentiated with T2 and ADC.

28.1.2.2 Extension

FIGO staging is summarized in Table 28.2.

Stage I. The carcinoma is strictly confined to the cervix (extension to the corpus would be disregarded) |

IA. Invasive carcinoma which can be diagnosed only by microscopy, with deepest invasion ≤5 mm and largest extension ≤7 mm |

IA1. Measured stromal invasion of ≤3 mm in depth and extension of ≤7 mm |

IA2. Measured stromal invasion of >3 mm and not >5 mm with an extension of not >7 mm |

IB. Clinically visible lesions limited to the cervix or preclinical cancers greater than stage IAa |

IB1. Clinically visible lesion ≤4.0 cm in greatest dimension |

IB2. Clinically visible lesion >4.0 cm in greatest dimension |

Stage II. Cervical carcinoma extends beyond the uterus, but not to the pelvic wall or to the lower third of the vagina |

IIA. Without parametrial invasion |

IIA1. Clinically visible lesion ≤4.0 cm in greatest dimension |

IIA2. Clinically visible lesion >4.0 cm in greatest dimension |

IIB. With obvious parametrial invasion |

Stage III. The tumor extends to the pelvic wall and/or involves the lower third of the vagina and/or causes hydronephrosis or nonfunctioning kidneyb |

IIIA. Tumor involves lower third of the vagina with no extension to the pelvic wall |

IIIB. Extension to the pelvic wall and/or hydronephrosis or nonfunctioning kidney |

Stage IV. The carcinoma has extended beyond the true pelvis or has involved (biopsy proven) the mucosa of the bladder or rectum. A bullous edema, as such, does not permit a case to be allotted stage IV |

IVA. Spread of the growth to adjacent organs |

IVB. Spread to distant organs |

MR findings are summarized in Table 28.3 [7].

Table 28.3

MR findings in cervix carcinoma (all types) correlated to FIGO staging

IA. No evidence of a mass lesion |

IB. Tumor completely surrounded by the hypointense stromal ring |

IIA. Segmental disruption of the hypointense upper two-thirds of vaginal wall |

IIB. Protrusion of the tumor into the cardinal ligament through a disrupted hypointense cervical stromal ring |

IIIA. Same finding as for stage IIA in the lower one-third of the vagina |

IIIB. Same finding as for stage IIB with obliteration of the entire cardinal ligament directly extending to pelvic muscles or with hydroureter |

IVA. Segmental disruption of the hypointense bladder or rectal wall or a segmental thickened rectal wall |

IVB. Evidence of mass lesions in distant organs |

Extension may involve:

1.

Mackenrodt’s ligament and ureter

Extension to the proximal part of the Mackenrodt’s ligament appears as tissue with irregular limits in continuity with the lateral border of the cervical tumor or as nodules. Signal intensity of this extension is very similar to the signal intensity of the cervical tumor on the different sequences. Extension to the ureter results in dilatation of the pelvic ureter above the obstruction; in some cases, CT can be helpful to precise this extension.

2.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Vagina (Figs. 28.3, 28.4, 28.5, 28.6, and 28.7)