Central Venous Catheter Repositioning Techniques

When central catheters are placed without the benefits of fluoroscopic guidance or the use of a guidewire, unrecognized malpositioning of the catheter tip can occur until a follow-up chest radiograph is obtained. Proper positioning of the catheter tip into the largest vessel possible is desired to reduce the incidence of phlebitis and thrombosis. These two complications can result, in part, from the relatively caustic or toxic properties of some infusates (i.e., total parenteral nutrition, chemotherapeutic agents) and from the decreased flow that occurs when small vessels are partially obstructed by the presence of the catheter. In addition, catheters can act as a nidus for thrombus formation, thus accentuating an already compromised situation. Repositioning of malpositioned catheters is desired as soon as possible following detection to minimize the risk of these complications.1,2 A number of simple techniques have been developed to allow for relatively easy and accurate repositioning of central venous lines.

Guidewire Technique

Guidewire Technique

A central venous catheter placed from a right or left subclavian vein approach may enter the ipsilateral internal jugular vein, contralateral brachiocephalic vein, or the azygos vein as opposed to its desired position in the superior vena cava. Before an attempted repositioning of a catheter, an injection of contrast through the catheter always should be obtained to rule out the presence of a large thrombus at the end of the catheter or vessel thrombosis. If only a small clot is present at the distal tip of the catheter, repositioning usually can be accomplished relatively easily; in addition, small clots at the distal end of the catheter, which impair its function, usually can be removed without consequence. If the vessel is completely thrombosed, a course of urokinase therapy administered through the catheter (20,000 U × 6 hours at 2000 to 4000 U per mL) may have to be administered to free the catheter from the vessel. Vessel thrombosis is more likely to occur when the catheter is malpositioned within the relatively small external jugular vein as opposed to the larger vessels. In addition to assessing the degree of vessel thrombosis, injection of the catheter should always be performed initially to ensure that the catheter tip is, in fact, within the vessel lumen (as opposed to subintimal or extraluminal). Catheters that are extraluminal should not be repositioned. If catheters are subintimal, the guidewire technique should not be used because the guidewire may perforate the vessel wall or cause further dissection rather than reposition the catheter.

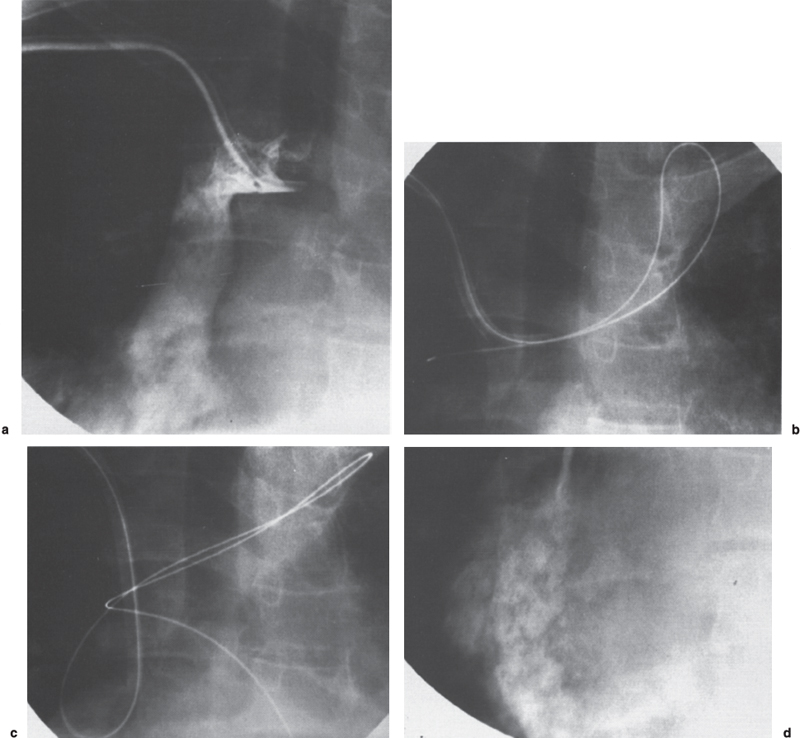

Regardless of whether the catheter is a standard-size single-, double-, or triple-lumen catheter, a 10F double-lumen Hickman, or a 13.5F double-lumen dialysis catheter, we prefer initially to attempt repositioning with an angled hydrophilic-coated guidewire (Terumo, Meditech, Watertown, MA). The guidewire is inserted through the catheter lumen until it exits the distal end of the catheter and is within the vessel lumen. The guidewire is further advanced and rotated until a small branch vessel or acute angle in the main vessel is reached. The guidewire is further advanced and rotated so that a loop in the guidewire is formed within the main vessel. Once a loop is formed in the guidewire, further advancement of the guidewire will have one of two results: (1) the guidewire will continue to double back along itself, and no significant torque will be built up within the guidewire; or (2) enough friction will occur that the guidewire does not double back along itself, and continued advancement of the guidewire will result in a buildup of force along the guidewire. As the guidewire is gently but continually advanced, the guidewire will buckle within the largest portion of the vessel or in the region of the confluence of the great veins. As the guidewire continues to be gently advanced, the buckle in the guidewire will increase in size and the catheter will gently ”back out” of the vessel in which it is located. As the catheter continues to back out into the main portion of the venous system and away from the branch vessel in which it was located, it typically will flip into the main venous system. For example, in a case of a central venous catheter that enters the subclavian vein but has its tip in the internal jugular vein, continued advancement of the guidewire typically forms a buckle in die guidewire and catheter in the region of the brachiocephalic vein. As the guidewire continues to be advanced, the buckle grows larger until the catheter flips into the superior vena cava. One should be careful with this maneuver so that unnecessary trauma is not imparted to the vessel in which the catheter lies. One should pay close attention to the patient because abnormal stress on the vein undoubtedly will result in patient discomfort. In addition, in an attempt to redirect a catheter from the internal jugular vein, the guidewire should not be advanced beyond the jugular bulb, nor should it enter the transverse sinus. Advancement of the guidewire beyond this region may result in extreme posterior auricular pain. In addition, there is small but real risk of transverse sinus thrombosis if significant venous trauma occurs.