Description

Points

Size

<3 cm

1

3–6 cm

2

>6 cm

3

Eloquence

Yes

1

No

0

Deep venous drainage

Yes

1

No

0

Endovascular Treatment

Endovascular embolization has become a pillar in the multidisciplinary treatment of AVMs [16, 17]. Endovascular treatment can be used as a preoperative adjunct for the curative resection of AVMs. This indication constitutes the largest use of endovascular techniques for AVMs, and the advent of the embolysate ethyl vinyl alcohol copolymer (EVOH) or Onyx (ev3, Irvine, CA) has greatly expanded the indications and safety of this approach [18]. In rare circumstances, embolization may be used as a curative modality for the complete occlusion of AVMs. This strategy is associated with an increased risk of complications, due to the aggressive nature of embolization needed to completely occlude the AVM nidus, and is rarely the strategy of choice in most centers [18, 19]. A third indication for endovascular treatment is its application as an adjunct before radiosurgery. Yet other indications are the use of embolization for targeted treatment of high-risk features of AVMs (such as intranidal aneurysms) or as a palliative tool to minimize patient symptomatology. In general, the indication to use embolization in the treatment strategy should take into consideration the added risk associated with this intervention. We adhere to the guidelines mentioned above and rarely embolize grade I or II AVMs. Embolization is commonly performed for grade III AVMs and is utilized as a part of multimodality regimen for more complex lesions.

Preoperative Embolization

The goal of preoperative embolization is reduction in the number of arterial pedicles feeding the nidus of the AVM, especially those vascular feeders that reside deep to the nidus and are difficult to access early in the surgical approach (Fig. 49.1). At our center we perform embolization procedures on the day prior to planned microsurgical resection. Although the timing of embolization and surgery are controversial, we are reluctant to leave the patient at risk for hemorrhage after the hemodynamic changes induced by the embolization. In the post-embolization period and prior to resection, patients with complex AVMs are kept sedated with strict blood pressure control. Others have postulated that surgery should be performed in a delayed fashion (2–3 weeks after embolization) to allow for normalization of hemodynamic parameters after embolization [20, 21].

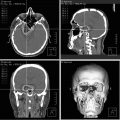

Fig. 49.1

Embolization as an adjunct to operative resection. This 52-year-old male presented to our clinical service after an intraventricular and parenchymal hemorrhage. (a) Axial computed tomography (CT) demonstrates the bleed pattern. Axial (b), sagittal (c), and coronal (d) CT angiography revealed an intraventricular AVM fed by branches of the posterior cerebral artery (PCA) with deep venous drainage. Anteroposterior (AP) (e) and lateral (f) right internal carotid artery (ICA) injections demonstrate that the primary arterial feeder of the nidus is the PCA and provides evidence of the early draining vein. Onyx was used to embolize a branch of the PCA feeding the nidus. AP (g) and lateral (h) projections post-Onyx embolization reveal diminished flow to the AVM with preservation of the draining vein. The patient underwent microsurgical resection of the AVM via a transcortical approach. AP (i) and lateral (j) ICA injections demonstrate minimal residual nidus left apposed to the brainstem. The patient was scheduled to receive radiosurgery to the residual nidus. Used with permission from Barrow Neurological Institute

Curative Strategies

Angiographic cures have been achieved in a subset of AVMs with embolization as a stand-alone therapy. Using cyanoacrylate-based glues (e.g., N-butyl cyanoacrylate [NBCA]), a complete occlusion rate of 20 % has been reported [19]; however, the more recent introduction of ethyl vinyl alcohol copolymer (EVOH) or Onyx has increased total obliteration rates to as high as 51 % [18] among all AVMs and up to 96 % for select AVMs with simple angiographic features [22]. AVMs most amenable to complete obliteration are those lesions with a small nidus, readily visible draining vein, and few arterial pedicles. These characteristics are common among grade I and II AVMs, which can readily be treated with surgery, with low resultant morbidity and mortality. As such, we rarely attempt a complete angiographic cure with embolization alone at our center. Another issue of concern with curative embolization is the question of durability of an angiographic cure with embolysates. Experience with surgical resection suggests that despite angiographic cure, residual blood flow is noted at the time of surgery through embolized vessels.

Pre-radiosurgery

Embolization can be selectively used in patients with deep-seated or complex lesions being considered for radiation therapy (Fig. 49.2). Embolization can shrink the AVM nidus thereby decreasing the volume that must be targeted for therapy with radiation. Despite obvious benefits of downsizing and reducing the complexity of AVMs with embolization, the embolysate may actually make targeting of lesions difficult by causing distortion of the nidus, thereby reducing the rate of AVM obliteration during the period of latency [23–25]. The process of embolization also creates discrete foci of AVM with intervening embolized nidus, which can make planning for radiosurgery more challenging [26]. Furthermore, the possibility of recanalization of embolyzed segments leads to uncertainty of the fidelity of the treatment. Nonetheless, for select complex AVMs, embolization and radiosurgery may be used as a last resort treatment option [27].

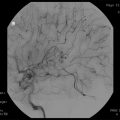

Fig. 49.2

Embolization as an adjunct prior to radiotherapy. This 28-year-old male with a grade V AVM presented to our service with a large diffuse lesion involving the internal capsule with deep venous drainage. (a) Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance (MR) scan reveals the diffuse and extensive nature of the AVM nidus. The patient underwent pre-radiosurgery embolization with Onyx. (b) T2-weighted axial MR images 3 years after radiosurgery demonstrate a significant reduction in the size of the nidus. The lesion was felt to be amenable to microsurgical resection. (c) Anteroposterior angiography with vertebral artery injection demonstrates the size of residual nidus and pure superficial drainage of the lesion. The patient underwent craniotomy with resection of the lesion. (d) Postoperative T1-weighted axial MR scan reveals complete resection of the lesion. Used with permission from Barrow Neurological Institute

Targeted Embolization

Targeted embolization can be used to treat angiographic features of an AVM that may predispose it to a higher risk of rupture. In general this strategy is used in cases when definitive treatment is not possible or is too risky. Features that increase the likelihood of rupture, so called high-risk features, include intranidal aneurysms, outflow venous stenosis, and the presence of a single deep draining vein (Fig. 49.3) [28–30]. Although partial treatment of an AVM affords no protection over the natural history of the lesion, treatment of high-risk features, such as intranidal aneurysms, decreases the likelihood of hemorrhage [31].

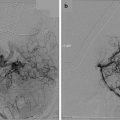

Fig. 49.3

Targeted embolization of AVMs. In select cases angiographic features of AVMs may predispose them to higher rates of hemorrhage. High-risk features predisposing to hemorrhage include intranidal aneurysms and venous outflow obstruction. (a) Anteroposterior (AP) angiography of the left vertebral artery demonstrates a thalamic AVM with multiple intranidal aneurysms fed from the left posterior cerebral artery. Given the location of this lesion in the thalamus, it was felt that the patient would benefit from treatment of high-risk features and close follow-up. (b) AP vertebral artery angiography demonstrates residual nidus after targeted embolization of the high-risk features with Onyx. Used with permission from Barrow Neurological Institute

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree