Chest Disease in the Immunocompromised Patient

Janet E. Kuhlman

John H. Juhl

J. E. Kuhlman and J. H. Juhl: Department of Radiology, University of Wisconsin Medical School, Madison, Wisconsin 53792-3252.

The immunocompromised patient is susceptible to a variety of infectious, inflammatory, and neoplastic disorders. The type of immunodeficiency and its severity correlate well with the complications encountered in the chest. In this chapter, chest diseases affecting the patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), the transplant recipient, and the neutropenic patient are reviewed.

OVERVIEW OF INFECTIOUS COMPLICATIONS

Several conditions alter a patient’s defense mechanisms and lead to susceptibility to organisms that may or may not be pathogens in normal persons. Diseases and organisms often associated with these conditions include the following:

Acute myelocytic leukemia and leukopenia—Pseudomonas, Staphylococcus, Aspergillus, and Mucor;

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia and lymphosarcoma—Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus, Cryptococcus, Pneumocystis, and herpes viruses;

Hodgkin’s disease—Cryptococcus, Listeria, Pneumocystis, and organisms causing tuberculosis (TB) and toxoplasmosis;

Myeloma and chronic myelocytic leukemia—S. pneumoniae, gram-negative bacilli, Pneumocystis, and the tubercle bacillus;

Renal transplantation—many bacteria, Cryptococcus, Pneumocystis, cytomegalovirus (CMV), and organisms causing toxoplasmosis, nocardiosis, and histoplasmosis;

Cystic fibrosis—Staphylococcus and Pseudomonas;

Sickle cell disease—S. pneumoniae and Salmonella;

Drug addiction—Staphylococcus, mixed anaerobes, Pseudomonas, and Candida;

Hypogammaglobulinemia—gram-positive bacteria, Pneumocystis, and viruses;

Chronic granulomatous disease of childhood—Serratia, Salmonella, and Staphylococcus;

Bone marrow transplantation—CMV, herpes simplex virus, gram-negative bacteria, fungi, Pneumocystis, and combinations of organisms such as CMV and Aspergillus or Pneumocystis.

This list is not complete, and many of the organisms listed can cause pneumonia in several of the conditions mentioned. In addition, several other organisms have been implicated as the cause of pneumonia in these patients. Many of them are unusual or rare, and some are not ordinarily pathogens. Mortality is high, and treatment may be very difficult, because multiple organisms are often found in these patients. Therefore, an aggressive approach, employing percutaneous needle aspiration, transbronchial lung biopsy, or, at times, open lung biopsy, may be necessary to obtain material for specific bacteriologic diagnosis. The pulmonary findings in most of these pneumonias are described elsewhere. Chest roentgenography is more useful in identifying the pneumonic process and following its course than it is in suggesting the organism responsible for the disease. When fever develops in a patient with one of the preceding diseases, an opportunistic pneumonia may be developing. Any opacity that was not present on an earlier chest radiograph should arouse the suspicion of pneumonia. Computed tomographic (CT) characteristics of pulmonary infections in the immunocompromised host are helpful in (1) documenting the presence of pulmonary disease at an early stage, (2) characterizing the pulmonary involvement based on CT patterns that may narrow the differential diagnosis considerably, and (3) planning of percutaneous, surgical, or bronchoscopic lung sampling for definitive diagnosis.

THE PATIENT WITH AIDS

AIDS is caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). First recognized in 1981, AIDS has continued to spread worldwide.136A In the United States alone, an estimated one million persons are HIV-infected.145,153 No vaccine or cure for AIDS has yet been developed, but significant progress has been made in prevention and treatment of infectious complications of AIDS and in slowing the progression of virus and its ability to destroy the immune system.177A Combination drug therapy including the use of protease inhibitors dramatically decreases the levels of detectable HIV organisms in infected patients. The use of zidovudine (AZT) and other antiviral treatments may also slow the progression of HIV disease in many patients. Prophylactic treatments for infections such as Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP), TB, and pneumococcal pneumonia have dramatically changed the occurrence of fatal pneumonias in HIV disease.153 Because of these major developments, it is now common to hear the phrase “living with HIV,” one indication of the improving life expectancy of HIV-infected persons.153 Long-term survivors are increasing in number, and almost 51% of HIV-positive patients in one San Francisco cohort are still alive after 11 years of follow-up.153

Manifestations of AIDS have changed as treatments have improved. Pulmonary infections such as PCP were often fulminant and lethal; now they are preventable with prophylaxis and represent survivable but also often recurrent problems in HIV-infected patients. In many ways, AIDS has become a chronic, slowly progressive illness, with tremendous variations in the course of the disease from one person to the next. Not all the new developments related to the AIDS epidemic have been positive, however. In large part because of AIDS, there has been a resurgence of TB in the last 5 years and the emergence of multiple-drug-resistant strains (see Chapter 24).

The face of AIDS in the United States also continues to change, from a disease confined primarily to homosexual men to a disease that affects all segments of society, with growing numbers of newly infected persons to be found in inner-city populations, among intravenous drug users, their partners, and offspring. Women and children currently are the fastest growing group of newly infected patients in the United States.10A

Pulmonary Disease in AIDS

Diseases of the chest continue to account for 65% of all AIDS-defining illnesses, and pulmonary infections cause the majority of life-threatening illnesses in AIDS patients.145 Radiologic diagnosis of pulmonary disease in AIDS can be difficult but rewarding when an integrated approach is used combining clinical information, radiographic pattern recognition, and an understanding of the natural history of HIV disease.81,94,115,125,164,212 HIV disease and AIDS encompass a spectrum of disease states from the asymptomatic carrier of the HIV to the patient with terminal AIDS. In between, varying degrees of immunosuppression exist, and it is the degree of immune suppression that best predicts the type of pulmonary disease likely to be present in an HIV-infected patient. An extensive variety of opportunistic infections cause pulmonary disease, and unusual manifestations are common. Multifactorial disease may be present—Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) with PCP, PCP with CMV, lymphoma with a disseminated fungal infection. Although few radiographic and CT manifestations are specific, certain patterns of involvement are encountered. Combining radiographic pattern recognition with knowledge of the clinical presentation, the CD4 count, the underlying risk group, and previous drug treatments can narrow the diagnostic considera-tions115,117,124,125,209 (Table 25-1).

HIV causes deficiencies in humoral, cell-mediated, and phagocytic responses, the most serious being progressive reduction in the number of CD4-positive helper T-cell lymphocytes (the CD4 count).145 The CD4 count correlates well with the type of AIDS-related disease encountered. More virulent organisms that are usually contained by cell-mediated immunity (e.g., TB) and encapsulated pyogenic bacteria that are usually kept in check by humoral defense mechanisms are frequently the first types of pulmonary infections seen, even before the CD4 count has dropped to 200 cells/mm3 and AIDS has been diagnosed. Reactivation TB and recurrent community-acquired pneumonias may be the presenting illness for previously undiagnosed patients with HIV infection. Opportunistic infections in HIV disease begin to occur when the CD4 count drops to 200 to 250 cells/mm3; P. carinii is the most common pulmonary pathogen. As the degree of immunosuppression becomes more severe and the CD4 count drops to less than 150 cells/mm3, less virulent organisms become successful pathogens, including fungal species. CMV and Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) infections usually occur in patients with CD4 counts of 50 cells/mm3 or less.145,164,165,209,233D It is at this severe level of immunosuppression that AIDS-related lymphomas usually surface.

Demographics and underlying risk factors for acquisition of HIV also affect the type of AIDS-related lung disease. TB is much more prevalent in intravenous drug users who are HIV-positive, in AIDS patients with prior TB exposure or a history of a positive PPD skin test, and in HIV-positive persons from TB-endemic countries such as Haiti.241 KS, on the other hand, occurs almost exclusively in homosexual or bisexual men and their partners who are HIV-positive. Septic emboli, recurrent staphylococcal infections, aspiration pneumonia, lung abscess, and empyemas are more common in intravenous drug users who have AIDS.124,241

Various treatments for AIDS and its complications significantly alter the manifestations of AIDS-related pulmonary infections.241 Antibiotic prophylaxis against PCP has

changed the prevalence and natural history of this infection in AIDS.165 Aerosolized pentamidine, another treatment for PCP, has been associated with cases of disseminated PCP, lymphatic calcifications, and upper-lobe and cystic forms of PCP. Widespread use of prophylactic antibiotics in patients with AIDS may also hamper diagnosis by masking culture results and obscuring the bacterial origin of pulmonary infections. AZT, antiviral agents, and the newer protease inhibitors, by slowing the deterioration of the immune system, will probably also alter the manifestations of AIDS-related illnesses in yet unknown ways.124

changed the prevalence and natural history of this infection in AIDS.165 Aerosolized pentamidine, another treatment for PCP, has been associated with cases of disseminated PCP, lymphatic calcifications, and upper-lobe and cystic forms of PCP. Widespread use of prophylactic antibiotics in patients with AIDS may also hamper diagnosis by masking culture results and obscuring the bacterial origin of pulmonary infections. AZT, antiviral agents, and the newer protease inhibitors, by slowing the deterioration of the immune system, will probably also alter the manifestations of AIDS-related illnesses in yet unknown ways.124

Pulmonary Infections in AIDS

Pneumocystis Infections

PCP is most commonly seen in patients with AIDS, but may also be encountered in patients with bone marrow or organ transplants and in any patient receiving corticosteroids or cytotoxic agents for the treatment of connective tissue disorders, hematologic disorders, or solid organ tumors28,198,208 (Figs. 25-1, 25-2, 25-3, 25-4, and 25-5). PCP may also occur in severely malnourished patients and was recognized as a cause of epidemic pneumonia in European orphanages back in 1952.233 A few cases of PCP have even been reported in elderly patients who had no identifiable underlying illness or evidence of immune deficiency.95

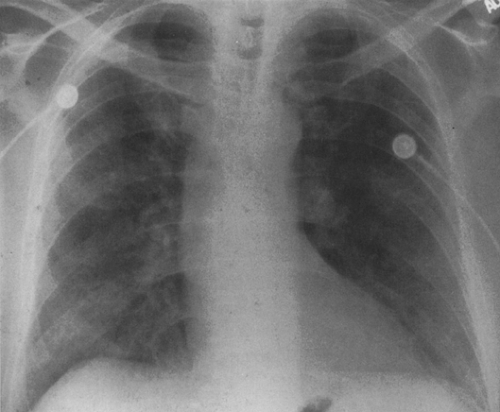

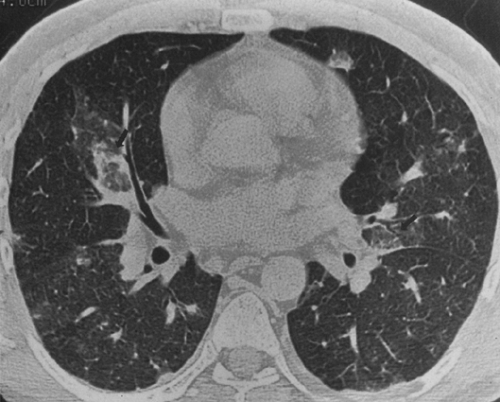

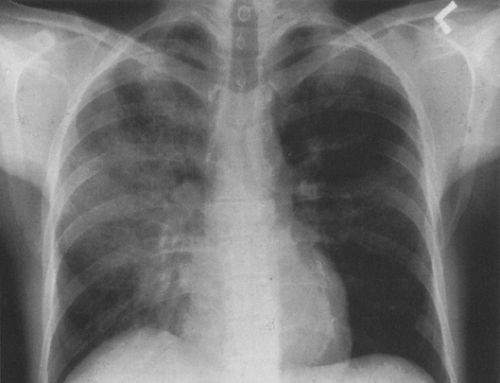

FIG. 25-2. Asymmetric involvement of the lungs by Pneumocystis pneumonia in a 27-year-old homosexual man with AIDS. The right lung is affected to a much greater extent than the left. |

PCP remains the most common cause of life-threatening infection in AIDS. Although PCP is still the most common index diagnosis for AIDS in this country, significant advances in treatment and prevention have resulted in a decline in the relative incidence of this infection in AIDS patients in the industrialized world.47,102,111,155A,158,165,199,216 Studies in the United Kingdom and Canada have shown a dramatic decrease in the percentage of hospital admissions for PCP in AIDS patients resulting from widespread use of prophylaxis.30,188 Both study populations were predominantly male and homosexual patients. Specific incidence figures for PCP depend on the geographic location, the risk category for AIDS exposure, and the ethnic group. In sub-Saharan Africa,

for example, TB and bacterial pneumonia have always been more common than PCP as index infections for AIDS.152 Prophylaxis has also decreased the number of recurrent infections due to PCP in this country. Without preventive prophylaxis, the relapse rate for PCP is approximately 60% in 1 year.71,123,198

for example, TB and bacterial pneumonia have always been more common than PCP as index infections for AIDS.152 Prophylaxis has also decreased the number of recurrent infections due to PCP in this country. Without preventive prophylaxis, the relapse rate for PCP is approximately 60% in 1 year.71,123,198

P. carinii was originally classified as a protozoan but is now believed to a species of fungus, based on analysis of ribosomal RNA.198 It is ubiquitous in nature and exists in two principal extracellular forms—a cyst and a trophozoite.199 Pneumonia in humans begins when the Pneumocystis trophozoite attaches itself to a type I alveolar epithelial pneumocyte by interdigitating with the host cell membrane. The host type I cell dies, creating a break in the alveolar-capillary membrane. Proteinaceous fluid then seeps out into the alveolar spaces, which become filled with a foamy, eosinophilic exudate containing trophozoites, cysts, fibrin, and dead cells.148,198,200 In the process, surfactant production is significantly hampered.123,198

The host immune response to PCP includes proliferation of type II pneumocytes, which attempt to repair the gaps within the alveolar-capillary membranes. Lung macrophages and plasma cells are also mobilized, resulting in a mild interstitial pneumonitis.149 As the lung tries to repair the damage, interstitial fibrosis develops.199 P. carinii is cleared from the lungs primarily by macrophages, but cell-mediated immunity, aided by the CD4+ T lymphocytes, is critical for host defenses against the infection. A fall in the CD4 count to 200 cells/mm3 or lower results in a dramatically increased risk for Pneumocystis infection.126,241 Even in the absence of CD4+ T lymphocytes, the infection induces mononuclear cells and macrophages to release destructive tumor necrosis factors and cytokines that cause a marked inflammatory response in the lung.224 An intact humoral antibody system is also important for fighting the infection, with immunoglobulin M (IgM) or IgG serum antibodies detectable in many patients after one or more episodes of PCP.224 CD4+ T lymphocytes probably resist infection both by cell-mediated

means and by promoting B-cell production of targeted PCP antibodies.123,224

means and by promoting B-cell production of targeted PCP antibodies.123,224

We do not know if PCP is caused by reactivation or reinfection. Most persons develop titers to the organism by the age of 3 years, suggesting that if the immune system becomes sufficiently impaired reactivation will occur.224 Reinfection or re-exposure may also be the cause of pneumonia. The report of a hospital outbreak of PCP among renal transplant recipients suggests that human-to-human transmission can occur, and animal studies suggest that airborne transmission of the disease is possible.26,198 The rate of PCP infection in AIDS patients also has a seasonal variation, with an increase in late spring and late summer/early fall, presumably owing to more favorable environmental conditions for the spread of the organism.149,150 Studies of health care workers caring for AIDS patients also indicate that some workers may be asymptomatic carriers of the organism.149 Therefore, re-exposure or colonization by the organism appears to occur, with disease developing when the immune system fails.149

Considerable variation exists in the clinical presentation of PCP.114A Severity and onset of symptoms differ in patients with AIDS compared with those with other forms of immunodeficiency.114A Nonproductive cough, increasing shortness of breath, and fever usually occur in both groups, but in the HIV-positive patient the onset of symptoms may be acute or subacute, even developing over weeks to months.198 Nonspecific constitutional symptoms of malaise may be the dominant feature in some AIDS patients with PCP. Other immunocompromised patients who develop PCP, including transplant recipients and those receiving corticosteroids or cytotoxic agents, usually present acutely with symptoms worsening over a 3- to 5-day period.198 PCP in infants and children may follow a particularly rapid and fulminant course.123,198

A number of laboratory abnormalities are seen with PCP infections: elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), decreased arterial oxygenation, widening of the alveolar-arterial oxygen gradient, and low diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO).198 Because P. carinii cannot be cultured, definitive diagnosis is made by identifying cysts on a methenamine silver stain or trophozoites on a Wright-Giemsa stain.224 Induced sputum samples from HIV-positive patients with suspected PCP have a sensitivity for detection of approximately 77%. In those with negative induced sputum results, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) is performed; it has a reported sensitivity of 86% to 97% in HIV-positive patients.224 Increased detection of the organism from induced sputum samples (80% to 90%) can be obtained by using immunofluorescent staining with monoclonal antibodies to the Pneumocystis organism. DNA amplification techniques show promise for ever higher detection rates which may in the future allow the diagnosis to be made from simple mouthwash samples, obviating the need for more specialized equipment.149,152,198 AIDS patients with sufficient clinical and radiographic evidence for PCP are often treated empirically for the infection, and only if the patient fails to respond to adequate therapy or if the presentation is atypical is bronchoscopy with BAL performed.149

In the HIV-positive patient, transbronchial biopsy is rarely used to establish a diagnosis of PCP because of the increased risk of pneumothorax and the higher mortality rate from the procedure in this population.28,228A In the non-AIDS patient, however, transbronchial biopsy and/or open lung biopsy may be resorted to more often, because PCP is less prevalent and less often suspected in this population and the diagnosis may be more difficult to establish.28

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is the most effective treatment for PCP. It is also the agent used for prophylaxis against Pneumocystis infection. Intravenous pentamidine is an effective alternative treatment, but side effects include renal dysfunction, bone marrow suppression, and liver failure.126,149,198 Aerosolized pentamidine given monthly was once used widely as a less toxic alternative to systemic intravenous pentamidine administration for prophylaxis against PCP, but it is now known to be less effective than oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Aerosolized pentamidine had other disadvantages as well. Diagnosis of relapse was made more difficult because previous treatment with aerosolized pentamidine decreased the diagnostic yield for organisms on BAL.69,176,198 Relapse rates with aerosolized pentamidine treatments were higher than when trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim) was used.126,199 Reports of disseminated, extrapulmonary infection and atypical clinical and radiographic presentations of PCP, including apical disease, cystic cavities, pneumothorax, and pleural disease in patients on aerosolized pentamidine, also began to appear in the literature just as this form of treatment began to be used widely.139,147,199 Specialized equipment is required for delivery of the aerosolized pentamidine, and this method of delivery could spread other pathogens such as the tubercle bacillus.139,147 Newer second-line drugs for PCP have been developed, including dapsone with trimethoprim, atovaquone, primaquine plus clindamycin, and trimetrexate, among others.126

Fulminant PCP infection with respiratory failure still occurs in 5% to 30% of patients with AIDS who present with PCP.216 The mortality rate is high, 45% to 72%, and once the patient requires intubation with mechanical ventilation the prognosis is poor.47 However, earlier stages of respiratory failure due to PCP can be reversed with the adjunctive use of corticosteroids.82B,155 Outcome in this setting is now comparable to that for other causes of acute res-piratory failure.64 Ironically, the outcome from a single episode of PCP is now better in the HIV-positive patient than in other immunocompromised patients.216 Corticosteroid treatment significantly improves survival and decreases intensive care unit admissions of patients with PCP with moderate to severe infection, and this treatment is recommended if the arterial partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) is less than 70 mm Hg or the alveolar-arterial gradient exceeds 35 mm Hg.69,126,149,198,216 Corticosteroids probably work by muting the destructive inflammatory response of the host to the infection.126,198

PCP in the Non-AIDS Patient

PCP also occurs in non-AIDS patients with other immunodeficiencies, including patients who are immunosuppressed because of bone marrow and organ transplantation, those receiving aggressive treatments for connective tissue diseases, and those receiving chemotherapy for hematologic disorders and solid organ tumors (see Figs. 25-3 and 25-4). Corticosteroids and/or cytotoxic agents are the primary predisposing risk factors.28 Organ transplant recipients often receive a number of immunosuppressive agents, including prednisone and cyclosporine, with or without azathioprine and antilymphocyte globulin to prevent rejection.248 Because of the increased risk for PCP in this setting, most transplant patients receive PCP prophylaxis for at least 1 year after organ transplantation.248 The incidence of PCP has dramatically declined in bone marrow and organ transplant recipients who receive prophylactic therapy.182,245 Lung transplant recipients receiving prophylaxis currently have a prevalence of PCP of only 2%. When PCP occurs within the first year after transplantation, it is usually a result of noncompliance or inability to take medications because of drug side effects.182 Late-onset PCP does occur in transplant recipients, often in those with graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and/or CMV infection. These two complications appear to further impair an immune system that is already suppressed by corticosteroids and antirejection drugs, increasing the likelihood of Pneumocystis infection.83,245 For this reason, PCP prophylaxis may be extended beyond the normal 1-year period in patients with chronic rejection, those with CMV infection, and those requiring higher dosages of immunosuppressive agents.6,123

Patients with connective tissue disorders that require aggressive treatments with immunosuppressive agents such as corticosteroids and cytotoxic agents, including cyclophosphamide and low-dose methotrexate, are at increased risk for PCP infection. These disorders include severe rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma, polyarteritis nodosa, polymyositis, dermatomyositis, polymyalgia rheumatica, psoriatic arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and Wegener’s granulomatosis.76,98,128 Some of these patients present with PCP only as their corticosteroid dose is being tapered, suggesting that the infection is present all along but becomes manifest only as the host inflammatory response is unmasked by the removal of corticosteroids.28,98,128

Radiographic Features of PCP

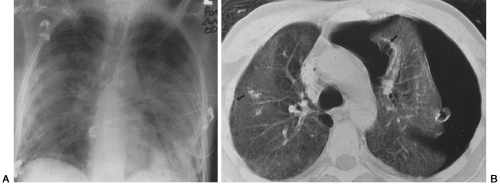

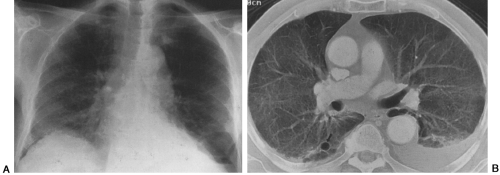

PCP can have a variety of radiographic appearances, but most cases show typical features: diffuse, bilateral, fairly symmetric, finely granular or reticular infiltrates that may appear interstitial or more air-space in nature49,79,106,123,165,198 (see Figs. 25-1 and 25-3). The pattern of distribution may vary, from primarily perihilar and lower-lobe disease to predominantly upper-lobe disease, a pattern often (but not exclusively) seen in patients undergoing prophylaxis with aerosolized pentamidine.41A Bilateral but asymmetric disease is also seen (see Fig. 25-2). Typically, pleural effusions and lymphadenopathy are not seen on the plain film. If left untreated, the infection can progress to diffuse air-space consolidation and adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).123

In AIDS patients with PCP who are undergoing treatment with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or intravenous pentamidine, clinical and radiographic improvement in the pneumonia usually occurs in 5 to 7 days.198 Apparent deterioration in the chest radiograph within the first few days of treatment may be caused, in some cases, not by progression of the infection, but by increasing edema secondary to leaky capillary membranes and volume overload from administration of intravenous antibiotics; this problem usually readily controlled with diuretics.79,164A Lack of response after 10 days indicates either treatment failure (a second-line drug is usually added) or the presence of a second pathogen. Although the chest radiograph usually clears significantly after 2 weeks of therapy, residual parenchymal changes may persist. These residual changes are even more evident on CT.123,165

Less Common Manifestations of PCP

Atypical patterns are seen in approximately 5% of PCP cases and have been reported in both AIDS and non-AIDS patients, with or without treatment with aerosolized pentamidine.106 Isolated lobar disease, focal parenchymal opacities or nodules, cavitating nodules or masses, miliary patterns, endobronchial lesions, and pleural effusions may all occur as a result of Pneumocystis infection.6A,87A,106,155A,165,204 In patients with lymphoma who are undergoing radiation therapy to the mediastinum, PCP may spare the radiated lung and cause pneumonia only outside the therapy port.179

Because of the widespread use of PCP prophylaxis, patients with PCP now often present earlier and with more subtle clinical and radiographic findings. Approximately 10% to 39% of patients with documented PCP have normal, near normal, or equivocal chest radiographs on initial presentation.7,37,49,103,176,225 For patients receiving aerosolized pentamidine, apical infiltrates, cystic lung disease, spontaneous pneumothorax, or disseminated extrapulmonary disease may be the first indication of primary Pneumocystis infection or relapse.165 Although these atypical findings are often associated with aerosolized pentamidine treatment, they can occur without its use and are not limited to HIV-positive patients.41A,106,123

Cystic PCP

A cystic form of the infection also exists and is characterized by cystic, cavitary, or pneumatocele-like lesions in the lung parenchyma that may be thin- or thick-walled and regular or irregular in shape.12,31,50,53,56,84,118,124,163,180,201,203,229,300

Cystic PCP is recognized more commonly in AIDS patients but rarely may be seen in other immunocompromised hosts (see Figs. 25-3 and 25-4). The cystic lesions may be surrounded by ground-glass infiltrates or be free of surrounding active pneumonitis. They have a predilection for the upper lobes and subpleural regions of the lung but are not found there exclusively.56 Spontaneous pneumothorax secondary to rupture of a subpleural cyst is a common presentation of this form of the infection12,31,50,53,56,84,118,124,164,180,201,203,230A (see Fig. 25-3).

Cystic PCP is recognized more commonly in AIDS patients but rarely may be seen in other immunocompromised hosts (see Figs. 25-3 and 25-4). The cystic lesions may be surrounded by ground-glass infiltrates or be free of surrounding active pneumonitis. They have a predilection for the upper lobes and subpleural regions of the lung but are not found there exclusively.56 Spontaneous pneumothorax secondary to rupture of a subpleural cyst is a common presentation of this form of the infection12,31,50,53,56,84,118,124,164,180,201,203,230A (see Fig. 25-3).

Based on chest radiographs, the prevalence of pneumatoceles or air-filled cystic lung lesions in PCP is approximately 10%.49,201 The number and extent of the cysts is often better appreciated on CT.124,165

Pathogenesis is still a mystery, but possible mechanisms for cyst formation include (1) focal lung destruction caused by proteolytic elastases, toxins, and tumor necrosis factor released from activated macrophages26A,53,57,146A,163,188A,194A,199A,229; (2) ischemic lung necrosis secondary to vascular invasion by Pneumocystis organisms163; (3) bronchial obstruction of small airways by Pneumocystis infection causing a ball–valve mechanism; and (4) necrosis caused by granulomatous reaction.56,112,229 Smoking, intravenous drug use, and repeated prior infections may also contribute to the formation of cystic lesions in some AIDS patients with PCP.31,56,118,123

Pathologically, two types of cystic lesions are identified. One type is intraparenchymal, necrotic, thin-walled, and surrounded by inflammation that contains Pneumocystis organisms.57,229 The other type of lesion is subpleural or apical in location and looks like a bulla; it has either a fibrous or granulomatous wall but no surrounding inflammation or organisms.57,118,229 One theory suggests that active, inflammatory lung cysts evolve into chronic, bland, bullous lesions by a process of migration, merger, and rupture of the cystic cavities into the subpleural space.57,229

Spontaneous Pneumothorax

Spontaneous pneumothorax occurs in 6% to 7% of AIDS patients with PCP.39 Most occur secondary to rupture of subpleural cysts39,92 (see Fig. 25-3). Pneumothoraces are frequently bilateral and often difficult to treat. Persistent air leaks caused by bronchopleural fistulae are common, and simple chest tube placement often fails to resolve the pneumothorax.19A,52A,52B,62A,80A,91A,96A,208A Refractory pneumothoraces may require pleurodesis with tetracycline, talc, or autologous blood or more invasive operative procedures such as lung stapling.19A,52A,52B,62A,80A,92 PCP with pneumothorax carries a high mortality rate, 33% to 57%, compared with an overall mortality rate from PCP of only 17%.39,123,140,198,291

Extrapulmonary Pneumocystis Infection

Dissemination of Pneumocystis infection beyond the lungs is rare; it is seen in fewer than 1% of patients premortem and in 2% to 5% of cases at autopsy.38,61,195,198,227 Disseminated infection has been recognized more frequently as the number of PCP cases has increased with the AIDS epidemic and more patients have been treated with aerosolized pentamidine.38,195 Because the distribution of aerosolized pentamidine is not uniform in the lungs, with better delivery at the lung bases than at the apices or periphery of the lung, smoldering infection may persist in some areas.106 In addition, systemic levels of the drug achieved by this route of delivery are low and do not prevent vascular invasion by the organism and subsequent spread of the infection through the lymphatics or the bloodstream.38,45A,139,195,219

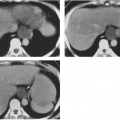

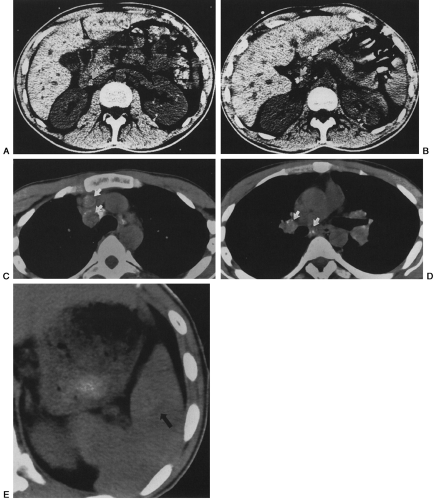

Pneumocystis can spread to almost every organ system, including the lymph nodes and spleen, liver, bone marrow, skin, thyroid, choroid plexus and meninges, adrenal gland, kidney, ear, bowel and peritoneum, heart, and pancreas.51,61,135,186,190,198,219 Patients with disseminated Pneumocystis infection may have no respiratory symptoms but signs related to other organ system involvement, such as hepatosplenomegaly and ascites, necrotic skin nodules, or fever of unknown origin.51 CT and ultrasound findings of dissemination may include punctate or rim-like calcifications within enlarged lymph nodes or in the spleen, liver, or kidneys and low-attenuation abscesses in the same organs61,82B,127A,135,191A (Fig. 25-6). Pleural and peritoneal effusions with punctate surface calcifications caused by disseminated Pneumocystis infection have also been reported.123,135 Pleural effusions in most cases of PCP are rare, unless the patient has disseminated disease or persistent subpleural lung infection with tissue invasion and subsequent extension into the pleural space.204,216

FIG. 25-6. A through E: Computed tomographic findings in extrapulmonary dissemination of Pneumocystis pneumonia. Punctate or ring calcifications in lymph nodes (white arrows), kidneys (arrowheads), or spleen (black arrow) can be seen in patients with disseminated extrapulmonary Pneumocystis carinii infection. (Reprinted from ref. 123, with permission.) |

Airway Involvement

P. carinii may affect the airways causing asthma-like wheezing in some patients. Bronchiectasis has been identified on CT in some AIDS patients who have PCP.143 Pulmonary function tests in such patients frequently demonstrate airway hyperactivity and reversible decreases in peak expiratory flow rates.206 Rarely, PCP can appear as an endobronchial mass lesion.68 Pathologic examination of lung tissue from patients with PCP also demonstrates bronchiolitis obliterans (BO), additional evidence that the small airways are adversely affected by this infection.229

Detection of Early PCP Infection

Early detection of PCP may be particularly difficult when the patient presents with nonspecific symptoms and a normal or near-normal chest radiograph. In these problematic cases, high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) or nuclear scintigraphy may be more sensitive than chest radiographs to detect infection.

Computed Tomographic Features of PCP

Several authors have described the CT findings of PCP in both AIDS and non-AIDS patients9,116,123,161,165,212 (see Figs. 25-3, 25-4, 25-5, and 25-6).

A spectrum of parenchymal abnormalities are seen on CT. Bilateral ground-glass opacities that may be diffuse or patchy are typically found.9 Often the pulmonary infection is strikingly patchy in its distribution, producing a mosaic pattern with abrupt transitions between normal and abnormal lung.116 Hartman and colleagues87 found that the presence of ground-glass infiltrates in the setting of AIDS was highly suggestive for PCP and that when a confident diagnosis of PCP was made based on CT findings in their study, it was correct in 94% of cases. Thickening of the interlobular septa may also be identified, often in cases of recurrent pneumonia, presumably because of either chronic interstitial inflammation, edema, or fibrosis.9,165 Residual linear fibrosis and apical and subpleural bullae may be identified on CT in patients with prior histories of PCP.118 In the cystic form of the PCP, CT is more accurate than chest radiographs in demonstrating the number and locations of cavitary/cystic lesions, particularly their predilection for the subpleural zones of the lung. Associated signs of disseminated infection that may be identified on CT include enlarged lymph nodes with calcifications and calcifications in the liver, spleen, kidneys, adrenal glands, and pleural or peritoneal surfaces.123

A spectrum of parenchymal abnormalities are seen on CT. Bilateral ground-glass opacities that may be diffuse or patchy are typically found.9 Often the pulmonary infection is strikingly patchy in its distribution, producing a mosaic pattern with abrupt transitions between normal and abnormal lung.116 Hartman and colleagues87 found that the presence of ground-glass infiltrates in the setting of AIDS was highly suggestive for PCP and that when a confident diagnosis of PCP was made based on CT findings in their study, it was correct in 94% of cases. Thickening of the interlobular septa may also be identified, often in cases of recurrent pneumonia, presumably because of either chronic interstitial inflammation, edema, or fibrosis.9,165 Residual linear fibrosis and apical and subpleural bullae may be identified on CT in patients with prior histories of PCP.118 In the cystic form of the PCP, CT is more accurate than chest radiographs in demonstrating the number and locations of cavitary/cystic lesions, particularly their predilection for the subpleural zones of the lung. Associated signs of disseminated infection that may be identified on CT include enlarged lymph nodes with calcifications and calcifications in the liver, spleen, kidneys, adrenal glands, and pleural or peritoneal surfaces.123

Nuclear Scintigraphy in the Diagnosis of PCP

Gallium-67 citrate scanning is 80% to 90% sensitive for the detection of PCP, but only 50% to 74% specific.77,173 Uptake of gallium in patients with PCP is variable and is affected by prior therapy, especially the use of aerosolized pentamidine, which alters typical patterns. Lymphoma in the lung accumulates gallium, but pulmonary involvement by KS does not. Gallium scanning is not a particularly rapid means of diagnosing PCP, because it often requires 24- and 48-hour scans.123

Indium-111–labeled human polyclonal immunoglobulins show lung uptake of tracer in the presence of PCP or any type of lung infection, but uptake is not specific for PCP. Neither KS nor lymphoma accumulates this tracer, however.149 Newer, radiolabeled monoclonal antibodies specific for Pneumocystis have been developed and demonstrate high sensitivity (86%) and specificity (87%) for PCP, but they are not widely available nor used on a routine basis.77

Magnetic Resonance Imaging in PCP

Lungs infected with Pneumocystis show higher than normal signal on T1- and T2-weighted images owing to the increased amounts of intra-alveolar fluid produced by this infection.141

Other Pulmonary Infections in AIDS

As the number of deaths due to PCP has declined in AIDS patients, other AIDS-related complications have increased in relative frequency and importance, particularly fungal infections and TB. The number of hospital admissions for these AIDS-related illnesses has also increased, including admissions for recurrent bacterial pneumonias and TB, particularly in certain risk groups (e.g., intravenous drug users).152 These shifts also reflect the changing epidemiology of AIDS in this country, from a disease seen primarily in homosexual and bisexual men to a disease seen increasingly in intravenous drug users and their sexual partners.47

Tuberculosis

TB is discussed in Chapter 24. A few additional comments regarding its presentation in the immunocompromised host, particularly the patient with AIDS, are presented here.

TB has become a serious infectious disease threat, not only to the AIDS community but also to the general population. Multiple-drug-resistant strains of TB have appeared in Florida and in New York City.58 In-hospital transmission of these strains from patient to patient and from patients to health care workers has been documented on HIV wards.185 Drug-resistant strains are increasing in incidence among HIV-positive prison inmates and intravenous drug users.58,59,124,185 Except for the drug-resistant strains, TB in AIDS responds well to therapy. Despite this response, TB is often the harbinger of rapid decline, with most AIDS patients dying within 14 months after onset of their TB infection.153

TB in HIV disease may be caused by reactivation or primary disease.59 In the normal host, cell-mediated immunity isolates tubercle bacilli after primary exposure, controlling the infection. When the T-cell system fails, however, reactivation of dormant bacilli occurs relatively early in HIV disease. The median CD4 count in HIV-infected patients with TB is about 350 cells/mm3, compared with less than 200 cells/mm3 in patients with PCP.58,145 Because it is more virulent than other opportunistic infections, pulmonary TB may be the first manifestation of HIV.

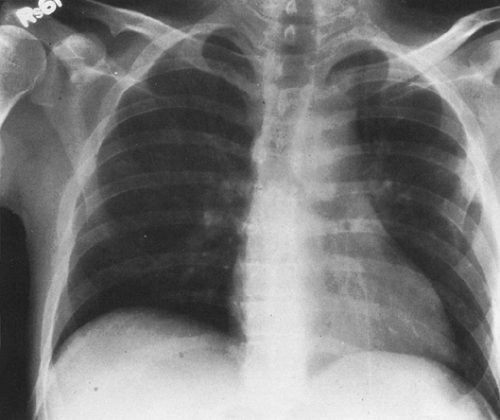

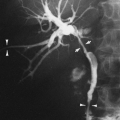

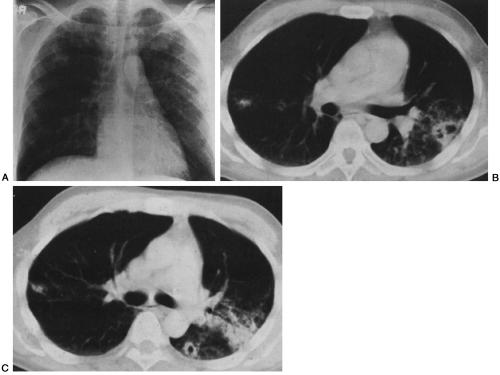

The radiographic features of TB in AIDS depend on the degree of immunosuppression.124 Early in HIV disease, TB tends to be seen in classic patterns: upper-lobe infiltrates, cavities, and bronchogenic spread (Fig. 25-7). Skin tests frequently are positive at this stage, and the infection is confined to the lungs in more than 75% of cases.145,241 In more advanced AIDS, the presentation is more varied and may resemble that of primary infection, progressive primary disease, or disseminated or miliary infection (Fig. 25-8). The skin test is positive in only 20% to 40% of patients, because most patients are anergic. Radiographic findings include more atypical presentations: diffuse infiltrates, multiple pulmonary nodules or masses, and prominent mediastinal adenopathy. In other patients, the chest film may be normal, even with disseminated disease.124 Extrapulmonary disease is found in 25% to 70% of AIDS patients and qualifies as an AIDS-defining illness.145,153,241 Disseminated TB in AIDS often involves the lungs, bone marrow, liver, spleen, kidneys,

and lymph nodes at autopsy. Miliary TB with marked necrosis and absent or poor granuloma formation is often found.59

and lymph nodes at autopsy. Miliary TB with marked necrosis and absent or poor granuloma formation is often found.59

FIG. 25-7. Tuberculosis mimicking Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) in an AIDS patient. A: The chest radiograph shows predominately upper-lobe infiltrates that are similar in character to those seen with PCP. B and C: The characteristics of the pulmonary infiltrates are better appreciated on computed tomography, which demonstrates cavities, areas of bronchogenic spread, and nodules that were found at bronchoscopy to be caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. (Reprinted from ref. 124, with permission.) |