Chest Infections

John H. Juhl

Janet E. Kuhlman

J. H. Juhl and J. E. Kuhlman: Department of Radiology, University of Wisconsin Medical School, Madison, Wisconsin 53792-3252.

The treatment and management of chest infections is a rapidly changing field. The emergence of new infections and drug resistance in common bacterial infections and tuberculosis (TB) is an ominous trend.14 As the number and types of patients with immunodeficiencies increase, whether from the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or as a result of treatment of other disorders, the spectrum of lung infections has rapidly increased. In this chapter, we discuss common and uncommon causes of acute lung pneumonia, both bacterial and nonbacterial in origin, as well as thoracic manifestations of TB and fungal infections. Diseases of the chest in the immunocompromised host are addressed in Chapter 25.

ACUTE PULMONARY INFECTIONS

Acute pulmonary infections cause significant mortality and morbidity. Despite ongoing advances in diagnosis and treatment, respiratory infections still account for almost half of all deaths from infection in the United States, and most of these are pneumonias of unknown origin in patients older than 65 years of age.14

Acute pneumonia may be caused by a variety of organisms. In some instances they produce a reasonably characteristic, gross pathologic pattern and therefore a recognizable roentgen pattern. The findings can be classified as follows.

Lobar (alveolar, air-space) pneumonia. This is exemplified by Streptococcus pneumoniae pneumonia. The organism reaches the periphery of the lung via the airways. Alveolar transudation (edema) is followed by migration of leukocytes into the alveolar fluid. As the disease progresses, peripheral homogeneous (consolidation) opacity spreads toward the hilum and tends to cross segmental lines. Alveolar (air-space) pneumonia is not necessarily confined to a lobe, nor does it involve an entire lobe in many instances. Therefore, the term lobar is a misnomer in most cases, but it is still used by many.

Bronchopneumonia (lobular pneumonia). This is often observed in staphylococcal infection of the lung. The disease originates in the airways and spreads to peribronchial alveoli. The process tends to be confined by interlobular septa, so the appearance is one of patchy disease causing poorly defined opacities. However, a variety of roentgen patterns may result, including a confluent consolidation resembling lobar (alveolar) pneumonia.

Acute interstitial pneumonia. This is usually caused by a virus or a mycoplasma. Often the interstitial involvement is masked by alveolar exudate. A variety of roentgen patterns is observed, but alveolar consolidation, if present, is not usually as confluent or as dense as in lobar or lobular pneumonia.

Mixed pneumonia. This is a combination of lobar, bronchopneumonia, and interstitial pneumonia.

In the following discussions, we describe the most common gross anatomic findings in the pneumonias of various causes, as reflected in chest roentgenograms. The roentgenographic manifestations of pulmonary infections are so varied that the pattern observed often provides little, if any, information regarding the causative organism. Therefore, in each instance it should be remembered that roentgen findings must be correlated with clinical, bacteriologic, and laboratory data to ascertain the correct etiologic diagnosis on which treatment is based. The role of the radiologist is to locate and define the extent of disease and any complications such as lung abscess and pleural effusion or empyema. An opinion as to whether the pattern is indicative of pneumonia should also be given. Serial films can be very useful in differentiating pulmonary edema from infection and are also used to follow the course of the pneumonia, particularly when clinical problems arise.

Bacterial Pneumonias

Pneumococcal Pneumonia

The acute pulmonary infection caused by S. pneumoniae is commonly termed lobar pneumonia. However, the infection does not usually involve an entire lobe and may be termed alveolar pneumonia. S. pneumoniae causes about 70% of bacterial pneumonia in the United States, often in otherwise healthy persons, but the disease is generally more severe in those with alcoholism, neoplastic disease, chronic pulmonary disease, or altered immunity. There are more than 82 serotypes of S. pneumoniae, but most of the pneumonias are caused by types 1, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, or 12. Type 8 is the most common. Type 14 causes pneumonia in children but rarely in adults. The mortality rate for pneumonia caused by type 3 is higher than for the others. Recently, antibiotic resistance of S. pneumoniae strains to penicillin and many other antibiotics has emerged. As a result, many infectious disease experts have called for a reduction in the indiscriminate use of empiric antibiotics and wider use of the pneumococcal vaccine.14

The organisms causing pneumococcal pneumonia are aspirated in droplets of saliva or mucus, so the lower lobes and posterior segments of upper lobes are most commonly involved. The onset is sudden, and the gross pathologic changes are evident early in the disease; roentgen findings can be observed within 6 to 12 hours after onset of symptoms. In some instances, dehydration may decrease the pulmonary manifestations of pneumonia, so that there is a delay in roentgenographic appearance of the disease. In these cases, hydration may result in apparent rapid development of visible roentgen signs, although there is conflicting evidence of this phenomenon. Involvement usually begins peripherally and spreads centripetally with homogeneous involvement that may cross segmental boundaries. The consolidation produced by the disease is manifested on the roentgenogram by homogeneous density. An entire lobe may be affected; more commonly only one or a few segments are involved. The density usually extends to the pleural surface.

A peripheral, nonsegmental, sublobar consolidation is seen when peripheral spread across segmental boundaries occurs.34 This tends to separate acute pneumococcal pneumonia from the pneumonias of segmental distribution, such as those caused by bronchial obstruction by tumor. The latter disease does not ordinarily cross the barrier formed by interlobar fissures and is therefore clearly defined by the fissure on either the frontal or lateral projection, depending on the lobe or segment infected (Fig. 24-1).

In pneumococcal pneumonia, all of the elements in the diseased lobe except the larger bronchi may be affected, resulting in almost complete airlessness. The larger bronchi can often be seen as air-containing, radiolucent tubes within the otherwise homogeneous density, the “air bronchogram.” There is often enough pleural involvement to result in elevation of the hemidiaphragm on the affected side because of pain. A small amount of pleural fluid, sufficient to obscure the depth of the costophrenic sulcus, is not uncommon. Because volume of the lobe or segment is not decreased significantly, opacity caused by this disease can be differentiated from that produced by atelectasis (Fig. 24-2).

Variations in the distribution of pulmonary consolidation may occur. The spherical pattern (round pneumonia) often reported in children is a form in which the well-circumscribed spherical consolidation may simulate a pulmonary

or paramediastinal mass.118 In patients with emphysema, radiolucent blebs surrounded by consolidation may simulate cavities. In some patients, the distribution of the disease is somewhat patchy or lobular, simulating the distribution in bronchopneumonia.34,48 Occasionally, an interstitial pattern may be observed, and sometimes a mixed alveolar and interstitial pattern is present. Therefore, as indicated previously, the roentgen findings are not diagnostic of pneumococcal pneumonia.

or paramediastinal mass.118 In patients with emphysema, radiolucent blebs surrounded by consolidation may simulate cavities. In some patients, the distribution of the disease is somewhat patchy or lobular, simulating the distribution in bronchopneumonia.34,48 Occasionally, an interstitial pattern may be observed, and sometimes a mixed alveolar and interstitial pattern is present. Therefore, as indicated previously, the roentgen findings are not diagnostic of pneumococcal pneumonia.

The bronchopneumonic pattern is common in hospitalized patients, who frequently have underlying diseases. Resolution is fairly rapid if there are no complications. It tends to start at the hilum and to progress peripherally in the lobe or segment. The opacity becomes more irregular and patchy during resolution, in contrast to its homogeneous character earlier in the disease. Focal atelectasis often develops.

Complications are few in otherwise healthy persons, because the disease responds well to antibiotics, which are often given at the first sign of respiratory infection. Complications include delayed resolution or nonresolution, empyema, and lung abscess. The roentgen finding in delayed resolution is persistence of density in the area, which becomes rather irregular and patchy but eventually clears. Very rarely the process clears incompletely, leaving some irregular fibrosis manifested by irregular strands of density in the segment or lobe, often with decrease in volume of the affected lung. The findings in empyema and lung abscess are discussed later.

Bronchopneumonia

Bronchopneumonia (lobular pneumonia) is an acute pulmonary infection, bacterial in origin, that usually occurs as a complication of various debilitating diseases, often at the extremes of life. It is most commonly found in the very young or very old who are afflicted with another disease. The infection is often mixed, so that several pathogenic bacteria can be isolated from the sputum. The disease originates in numerous adjacent areas of the lung, resulting in scattered foci of inflammation that vary in size and shape but produce enough density to be visible on the film. The inflammatory disease does not cross septal boundaries. Therefore, the pattern of disease is discontinuous or patchy.

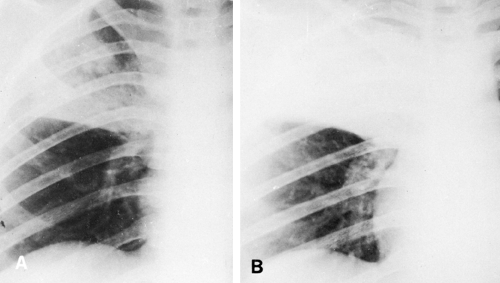

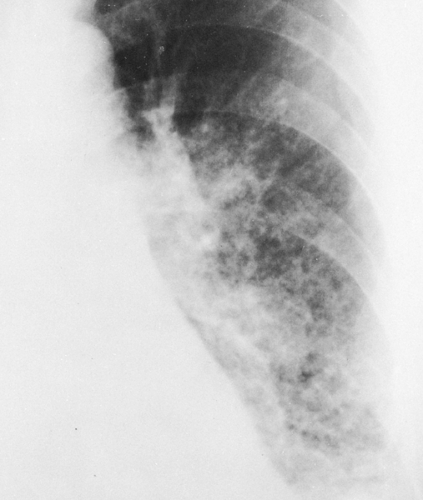

The roentgen findings in bronchopneumonia are varied, because the disease may be localized to a single lobe or segment or may involve all lobes. The pneumonic consolidation causes densities of varying sizes that are usually rather small and poorly defined and may be described as mottled. The disease may progress so that these small areas coalesce to form large, irregular opacities. The location is usually basal, but disease may occur anywhere in the lung (Fig. 24-3). It often occurs as a complication of another pulmonary disease, which may obscure the pneumonia or vice versa. It is particularly difficult to define and diagnose when it occurs as a complication in cardiac failure with pulmonary congestion and edema, which also cause basal opacity. It is also difficult to differentiate from other acute or subacute pulmonary diseases such as adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Occasionally, the process is extremely widespread and simulates miliary pulmonary disease, with small, poorly defined nodules scattered uniformly throughout both lungs. Because bronchopneumonia produces a variety of roentgen patterns and is caused by a number of organisms, its designation is now used as a descriptive term rather than a definitive one as far as etiology is concerned. In contrast to alveolar pneumonia, bronchopneumonia originates

in the bronchial airways and involves the surrounding parenchyma. As indicated, it may become confluent and then resemble alveolar pneumonia. It should be remembered that neoplasms can be masked by patchy focal pneumonia, and if clinical symptoms persist unduly, progress roentgenograms as well as cytologic studies should be recommended.

in the bronchial airways and involves the surrounding parenchyma. As indicated, it may become confluent and then resemble alveolar pneumonia. It should be remembered that neoplasms can be masked by patchy focal pneumonia, and if clinical symptoms persist unduly, progress roentgenograms as well as cytologic studies should be recommended.

Aspiration Pneumonia

Aspiration pneumonia is usually a mixed bacterial infection caused by aspiration of foreign material into the bronchial tree. The causes are numerous and range from aspiration of vomitus by a postsurgical or semicomatose patient to aspiration as a result of paresis or paralysis of the pharyngeal muscles. Tracheoesophageal fistula, gastroesophageal reflux, and various other esophageal lesions can also cause aspiration pneumonitis. Gram-negative organisms included in the aspirate may produce pneumonia followed by necrosis and abscess formation.130 This complication is discussed in the section on lung abscess.

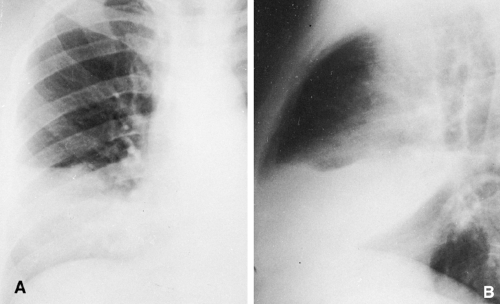

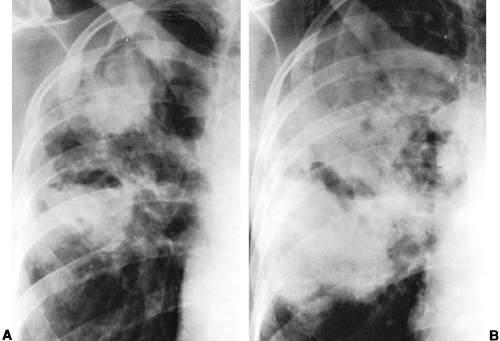

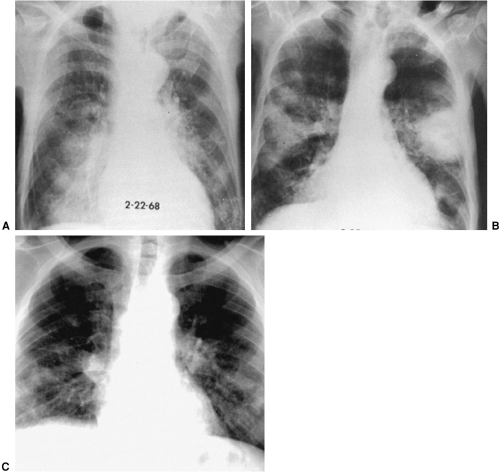

The radiographic findings vary with the extent of disease and its location. The right lower and middle lobes are most frequently affected, but involvement of the left lower lobe is not unusual. Irregular, poorly defined areas of increased density are seen and may be extensive (Fig. 24-4). Early in the disease these densities are focal, but later they may become conglomerate. In some instances the disease is acute and clears rapidly as the patient recovers from the condition that produced the aspiration. In other instances the pneumonia results from a chronic disease, and repeated aspiration leads to chronic basal pneumonitis, which causes patchy or linear basal opacity (Figs. 24-5 and 24-6). Aspiration of acid-containing gastric contents (Mendelson’s syndrome), can produce a chemical pneumonitis causing pulmonary edema, often in a dependent portion of one or both lungs. The appearance is similar to basal pulmonary edema of other causes. The roentgen findings are therefore varied, and it may not be possible to differentiate this basal inflammatory disease from other nonspecific basal pneumonia or from the chronic pneumonia associated with bronchiectasis. However, correlation of the history with clinical and roentgen findings usually leads to the proper diagnosis.

FIG. 24-5. Chronic aspiration pneumonia. The pneumonia in the parahilar areas and at the right base is somewhat more clearly defined and stringy than the acute process shown in FIG. 24-4. This patient had partial esophageal obstruction and had aspirated intermittently for several months. |

Pneumonia in Children

Differences in response to pulmonary infection in infants and young children, compared with older children and adults, are probably based on anatomic and immunologic factors.9,64 Airways are small, soft, and easily collapsible; resultant air trapping with overinflation can be found in a variety of infections in the first 12 to 18 months of life. In the newborn period, B streptococcal pneumonia causes an appearance similar to that of hyaline membrane disease. In fetal aspiration syndrome, rapid roentgenographic changes result as the aspirated material is cleared and overinflation disappears.

Staphylococcal pneumonia has a very rapid course, with early development (within hours) of effusion, empyema, and bronchopleural fistula with pyopneumothorax or lung abscess.90 Pneumatoceles are very common as the pneumonia clears.

Upper-airway infection may be associated with pulmonary disease, so a chest roentgenogram may be the initial study. When lungs are hypoaerated or edematous, obstruction due to epiglottitis should be suspected.

It is very important to correlate the roentgen findings with clinical signs and symptoms. For example, Chlamydia trachomatis causes conjunctivitis in neonates and may produce pneumonia which is interstitial, scattered, and bilateral and is associated with overinflation of the lungs. Cough is often the only symptom, so a chest film showing these findings in a neonate with conjunctivitis should suggest the diagnosis.113

Klebsiella (Friedländer’s) Pneumonia

Klebsiella pneumonia is a confluent alveolar type of pneumonia caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae. The disease occurs most frequently in elderly and debilitated patients. The onset is usually sudden, and the illness is often fatal within a few days. It may begin as bronchopneumonia manifested by patchy areas of opacity, usually in one or both upper lobes, but spreads rapidly to become confluent. It may involve an entire lobe. The involved lobe tends to increase in volume, resulting in convexity of the adjacent interlobar fissure. Extensive destruction of tissues leads to abscess formation in many of these patients, and the abscess cavities are typically thin walled, if a wall can be demonstrated (Fig. 24-7). Often, the confluent pneumonia surrounding the cavity obscures its actual wall. At times the necrosis is extensive and extremely large cavitation results when the necrotic material sloughs out. Pleural effusion is common, and empyema often follows the effusion. In the more chronic form, the disease tends to be patchier, the cavitation is smaller, and the lesions may closely simulate those of TB. Pneumatoceles may occasionally occur during resolution of Klebsiella pneumonia.

The diagnosis should be suspected when a rapidly progressing confluent pneumonia is observed in one or both upper lobes, resulting in increased lung volume, in which cavitation forms quickly. When the disease progresses more slowly, it is often less confluent, and its distribution in one or both upper lobes plus the presence of cavities often leads to a mistaken diagnosis of TB. Bacteriologic studies are then needed for differentiation. In patients who survive, a considerable amount of fibrosis may result, leading to contraction of the lobe with secondary changes in the thorax resulting from the loss of lung volume. In this respect, the disease may resemble chronic TB.

Enterobacter and Serratia are similar gram-negative bacteria that cause pneumonia infrequently. The most common of these is Serratia marcescens, which usually causes either a focal pneumonia or a diffuse process that may involve

several lobes. Pleural effusion is common. Both Enterobacter and Serratia are usually found in debilitated hospitalized patients, often in association with other organisms as a cause for pulmonary infection. As an opportunistic pathogen in immunosuppressed patients, Serratia may produce a necrotizing bronchopneumonia but usually does not cause a frank lung abscess (Fig. 24-8).

several lobes. Pleural effusion is common. Both Enterobacter and Serratia are usually found in debilitated hospitalized patients, often in association with other organisms as a cause for pulmonary infection. As an opportunistic pathogen in immunosuppressed patients, Serratia may produce a necrotizing bronchopneumonia but usually does not cause a frank lung abscess (Fig. 24-8).

Staphylococcal Pneumonia

Pneumonia caused by Staphylococcus aureus may be primary in the lungs or secondary to a primary staphylococcal infection elsewhere in the body. In the secondary type, there is hematogenous spread of the organism, whereas in the primary type the pulmonary spread is usually bronchogenic. The disease usually occurs in debilitated adults and in infants during the first year of life, and recurrent staphylococcal infections are common in patients who use intravenous drugs and those with AIDS. The onset of the illness is usually abrupt, with severe prostration. Death may occur within 24 to 48 hours. Because some of the many areas of involvement occur adjacent to the pleura, it is common to have pleural infection with empyema and bronchopleural fistula.

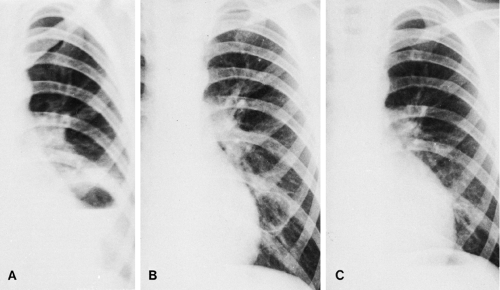

In children, the roentgen findings are rather characteristic and consist of dense areas of pulmonary involvement that may be segmental and local or diffuse.90 Consolidation rapidly spreads to involve a whole lobe (confluent bronchopneumonia); bronchi are usually obscured by exudate, so an air bronchogram is not ordinarily seen. Pleural effusion, empyema, and pneumothorax are common, and pneumatoceles are often noted. Abscess formation may also occur, and coalescence of small abscesses is frequent. A pneumatocele is distinguished from an abscess by its thin wall and rapid change in size. The pathogenesis of pneumatoceles is not known with certainty. The most popular theory hypothesizes that a check-valve obstruction develops between the lumen of a small bronchus and the adjacent interstitium. Multiple pneumatoceles may develop, usually in the first week of the disease, and they may become very large. Accumulation of fluid with air–fluid levels is common during the active phase of pneumonia. Pneumatoceles may persist for months but usually disappear completely (Fig. 24-9). In adults the findings are not as characteristic. Pneumothorax and pneumatocele are less common but do occur, and pleural effusion and empyema are not as common as in children, with the exception of patients with AIDS and intravenous drug users. Abscesses are slightly more common than in children and tend to coalesce (Fig. 24-10). The disease is

usually bilateral, may be diffuse and somewhat nodular, but is seldom lobar in distribution.

usually bilateral, may be diffuse and somewhat nodular, but is seldom lobar in distribution.

FIG. 24-10. Staphylococcal pneumonia. There is extensive disease in the left lower lobe, in which numerous small, rounded, lucent areas represent small pneumatoceles or abscesses. |

Pleural effusion, often resulting in empyema, occurs in about one half of the patients. Rapid change and lack of correlation between severity of clinical symptoms and roentgen findings are often observed. Resolution is usually slow in both children and adults. When the disease is hematogenous, septic emboli may cause multiple small abscesses and widespread, small foci of pneumonia.

Streptococcus pyogenes Pneumonia

Pneumonia caused by S. pyogenes (Lancefield group A, hemolytic streptococcus) usually occurs after such acute infectious diseases as measles and influenza. This disease is now rare. It is roentgenographically similar to staphylococcal pneumonia in the frequency of pleural involvement, including empyema if antibiotic therapy is not initiated promptly. The pulmonary involvement has a tendency to be more diffuse and interstitial in type than in staphylococcal pneumonia, with fine opacities radiating outward to the periphery from the hila. The combination of rapidly developing, hazy, nodular opacities in an acutely ill patient with subsequent cavitation in many of the areas is highly characteristic of either staphylococcal or streptococcal pneumonia, with the former more likely. S. pyogenes infections usually do not cause pneumatoceles.

Tularemic Pneumonia

Tularemia is an infectious disease caused by Francisella tularensis, a small gram-negative bacillus. It is a disease of small animals and may spread to humans directly from the animals.127 The most common mode of infection is through the skin of hunters who dress small game. The infection may also be transmitted by means of tick bites as well as the bites of horse and deer flies. Pulmonary involvement in the form of pneumonia resulting from this organism is present in approximately 50% of humans affected. The roentgen findings are not characteristic, but some authors have reported a high incidence of oval lesions resembling an abscess without cavitation. However, others have indicated a great variability in pulmonary findings.91 The infection may produce unilateral or bilateral pulmonary inflammatory disease, which is usually poorly circumscribed. Occasionally, the distribution is lobar, resulting in consolidation of an entire lobe. The infection is commonly a basal one, and there is usually more disease on one side than the other, so that it is asymmetrical when bilateral. A small amount of pleural effusion is not uncommon,26 and hilar lymph-node enlargement is also present in many instances. The time required for resolution varies widely. In some patients complete clearing may occur within 7 to 10 days, and in others the disease may persist for 6 weeks. Because the roentgen picture is not characteristic, the diagnosis must be confirmed by laboratory methods. The organisms are difficult to isolate from the sputum, but if the disease is suspected, its presence can be proved by means of agglutination tests.

Brucellosis Pneumonia

Brucellosis in humans in the United States is usually caused by Brucella suis. Pulmonary involvement is rare, and symptoms are usually mild.41,103 The roentgen findings are varied. Strands of opacity that radiate outward from the hila are often associated with hilar adenopathy and may be bilateral. Pleural involvement with effusion is occasionally encountered. In other instances, widespread miliary disease that resembles miliary bronchopneumonia is found. Solitary, circumscribed pulmonary nodules have also been described. The pulmonary roentgen changes appear quickly but tend to persist for long periods with very slow resolution. The diagnosis cannot be made on roentgen examination but must depend on the results of bacteriologic studies, agglutination, and skin tests. Calcifications in the spleen that have a typical appearance may be a clue to the diagnosis in the patient with the appropriate exposure history.8

Pertussis Pneumonia

Whooping cough is usually caused by Bordetella pertussis. The organism may also cause pneumonia, an unusual but not rare complication. The pulmonary disease begins in the paroxysmal stage of whooping cough and extends into

the resolution phase. It is usually found in children but may occur in adolescents and adults.

the resolution phase. It is usually found in children but may occur in adolescents and adults.

The pulmonary disease tends to be central, with radiating parabronchial strands of opacity. The radiographic findings resulting from this distribution of disease consist of blurring of the cardiac margins and an irregular appearance termed the “shaggy heart” pattern. There may also be some subsegmental areas of consolidation as well as scattered areas of atelectasis, presumably caused by mucus plugs, particularly in older children and adults. In some instances, the pneumonia may be caused by other organisms complicating whooping cough, a widespread bronchopneumonia.

Pseudomonas Pneumonia

There is an increasing incidence of pneumonia caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a gram-negative bacillus. Cases usually occur among hospitalized patients and are often related to the use of antibiotics, steroids, and immunosuppressive and cytotoxic drugs. There is evidence that positive-pressure breathing apparatus,57 suction and nebulizing devices, and tracheostomies are major factors in the development of this disease. P. aeruginosa is a water-associated organism found in many environmental sources, both in the hospital and outside it.117 The causative organism is extremely difficult to eradicate once pulmonary disease is established.

Several roentgen patterns of pulmonary involvement have been described: (1) bilateral pneumonic consolidation, with early patchy, scattered disease progressing and coalescing to involvement of the major portions of both lungs; (2) extensive bilateral pneumonic consolidation with abscess formation (abscesses may be multiple and small or few and large); (3) diffuse nodular or patchy densities with or without abscess formation; and (4) unilateral pneumonia, similar to the coalescent bilateral pneumonia. Many species of Pseudomonas are angioinvasive. Pathologic specimens show that bacterial colonies actually invade pulmonary blood vessels and cause a vasculitis and thrombotic occlusion. This predisposes areas of Pseudomonas pneumonia to undergo necrotic infarction, and lung cavitation is a prominent feature of many Pseudomonas infections.29 Therefore, almost any pattern may occur, so the radiographic findings are not diagnostic (Fig. 24-11). Pleural effusion may occur, but it is not a prominent feature of the disease. There is evidence that the presence of P. aeruginosa in the sputum of patients with chronic lung disease indicates underlying bronchiectasis.

Although most Pseudomonas infections occur in debilitated or hospitalized patients, they can occur in otherwise healthy persons. Serious, even fatal, Pseudomonas pneumonias have been associated with use of home and motel whirlpool spas and jacuzzis, presumably because of inhalation of large numbers of aerosolized bacteria from contaminated units into the lungs.68,117

Melioidosis, which is caused by infection with P. pseudomallei, is endemic in the tropics, chiefly in India, Burma, Sri Lanka, and South America. Since the Vietnam War, sporadic cases have been reported in the United States, chiefly in Vietnam veterans.19 The infection may be acute or chronic. The acute form is more common and is characterized by indistinct nodular disease that is often widely scattered but tends to involve the upper lobes. The nodules coalesce and cavitate in a high percentage of cases. The chronic form simulates pulmonary TB, because the nodules often involve the upper lobes and frequently cavitate. Hilar adenopathy is uncommon, and pleural effusion is rare.

Occasionally, pulmonary cavitation appears acutely years after the initial infection, so it should be suspected when a parenchymal cavity appears in an apparently healthy patient who was in an endemic area some years earlier.

Anaerobic Bacterial Pneumonias

Several anaerobic organisms may cause pulmonary infection. They include, among others, Bacteroides fragilis, Bacteroides melaninogenicus, and Bacteroides oralis; members of the genera Fusobacterium, Clostridium, and Eubacterium; and the gram-positive cocci of the genera Peptostreptococcus and Peptococcus. Most of the infections are caused by several organisms, because many are caused by aspiration of oral secretions, particularly in patients with poor oral hygiene. They may also occur in diabetic patients, those with malignant disease, and immunosuppressed patients. An alveolar type of pneumonia, which may be extensive, is usually produced. The right lower lobe is the most common site, but frequently more than one lobe is involved. About one half of patients have pulmonary disease only, about one fourth have pleural and parenchymal disease, and the remainder have only the pleura involved, usually with empyema. Abscess formation and necrotizing pneumonia are common complications. Abscess occurs in more than 50% of patients with pulmonary disease. Bronchopleural fistula may also complicate the disease. Anaerobic bacteria therefore are a prominent cause of aspiration pneumonia, lung abscess, necrotizing pneumonia, and empyema. The mortality rate is high in these patients, many of whom have depressed immune responses or leukopenia.13

Other Bacterial Pneumonias

Pneumonia caused by infection with Proteus vulgaris is largely basal, may be alveolar or lobular in distribution, and tends to produce cavitation. It may cause a decrease in volume of the involved lung. Rarely, Escherichia coli causes pneumonia, which is usually multilobar and basal. Pneumatoceles are occasionally seen in this infection, and the alveolar pneumonia caused by this organism rarely results in massive cavitation. Pleural effusion is common.

Pneumonic involvement may occur in typhoid fever, usually as a bronchopneumonia with cavitation, pleural effusion, or empyema. Salmonella organisms other than Salmonella typhosa may produce a similar pattern in the lung. An

acute miliary pattern has also been described in salmonella bacteremia.42 Hemophilus influenzae, type B, is a rare cause of pneumonia9 that is being seen increasingly in HIV-positive patients as a cause of pneumonia.

acute miliary pattern has also been described in salmonella bacteremia.42 Hemophilus influenzae, type B, is a rare cause of pneumonia9 that is being seen increasingly in HIV-positive patients as a cause of pneumonia.

In adults, these infections appear as acute lobular lower-lobe pneumonia or as a more confluent lobar alveolar process. The latter is somewhat more common. Pneumatoceles are rare but have been reported. Patients with alcoholism, who are immunocompromised, or who are undergoing chemotherapy are at risk. In infants, pleural effusion and empyema are common in addition to extensive alveolar disease. The latter may be a patchy, segmental type of density, but a variety of manifestations have been described, including reticular or linear, nodular, reticulonodular, ground-glass, and honeycomb patterns. Pleural effusion is fairly common and may be complicated by empyema. Cavitation is rare; roentgenographic findings clear slowly.

Pulmonary involvement also occurs in patients with anthrax or bubonic plague. In anthrax pneumonia, there is often substantial mediastinal lymph node enlargement, pleural effusion, and sometimes intrapulmonary hemorrhage in addition to extensive pulmonary disease. Plague can often involve the lung.5 In secondary pneumonic plague, bilateral small densities are the most common early manifestation. The disease may spread to involve much of the lungs with a dense alveolar process, which is often fatal. Rarely, the pattern is that of bilateral extensive mottled densities, which resemble the pattern of ARDS. This pattern reflects intravascular coagulopathy in some instances.

Legionnaires’ Disease

Legionnaires’ disease, which affected almost 200 people at the Legionnaires’ Convention in Philadelphia in July

1976, is caused by the aerobic, gram-negative bacillus Legionella pneumophila.27 Since this original description, 34 Legionella species and 52 serogroups have been isolated, with about half proving pathogenic to humans. The bacteria is associated with water reservoirs, including air-conditioning cooling towers.116 Clinically, the acute disease is characterized by a high fever, chills, and a nonproductive cough, often associated with chest pain, malaise, muscle and abdominal pain, headaches, and gastrointestinal symptoms. Hyponatremia and elevated creatine phosphokinase are two abnormal laboratory results that can occur with Legionnaires’ disease but are not often present in patients with other community-acquired pneumonias.116 Since the outbreak in Philadelphia, many sporadic and local outbreaks throughout the United States have been reported. Predisposing factors include smoking, alcoholism, diabetes, heart disease, and immunosuppression.

1976, is caused by the aerobic, gram-negative bacillus Legionella pneumophila.27 Since this original description, 34 Legionella species and 52 serogroups have been isolated, with about half proving pathogenic to humans. The bacteria is associated with water reservoirs, including air-conditioning cooling towers.116 Clinically, the acute disease is characterized by a high fever, chills, and a nonproductive cough, often associated with chest pain, malaise, muscle and abdominal pain, headaches, and gastrointestinal symptoms. Hyponatremia and elevated creatine phosphokinase are two abnormal laboratory results that can occur with Legionnaires’ disease but are not often present in patients with other community-acquired pneumonias.116 Since the outbreak in Philadelphia, many sporadic and local outbreaks throughout the United States have been reported. Predisposing factors include smoking, alcoholism, diabetes, heart disease, and immunosuppression.

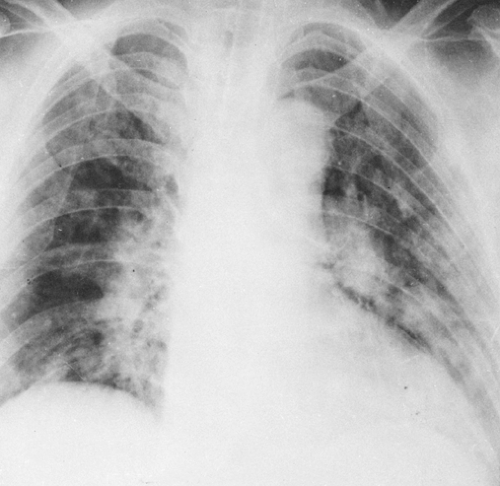

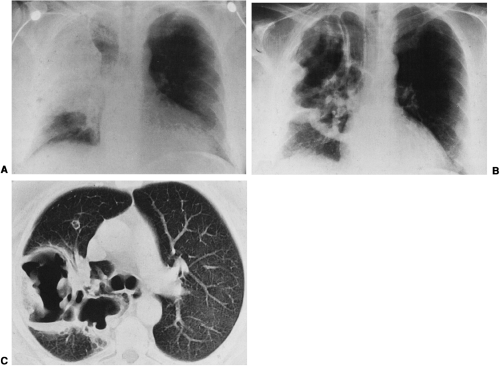

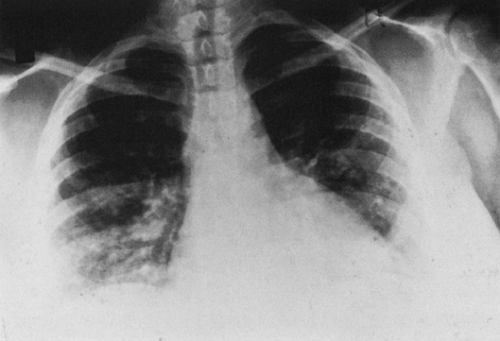

Roentgen findings are largely those of an alveolar pneumonic process that is bilateral in about one half of the reported cases (Fig. 24-12). There tends to be lower-lobe predominance. The alveolar disease may have a lobar or lobular distribution. At times, the alveolar process appears as a large, very poorly marginated, generally round or oval opacity. Some of these are central and some peripheral; they may be unilateral or bilateral. The round lesions appear to be somewhat more common than any other roentgen manifestation. The round, mass-like lesions often progress rapidly to involve an entire lobe. Early in the disease there may be patchy, ill-defined opacities that in many cases progress to a lobar pattern. One patient has been reported in whom there was virtually universal involvement of both lungs by an alveolar process in which air bronchograms were very prominent. Cavitation, presumably a result of necrotizing pneumonia, has been reported in several patients, most of whom were immunosuppressed. One patient has been reported in whom pneumatocele formation and spontaneous pneumothorax were manifest. Pleural effusion may occur, but its incidence is difficult to evaluate because many of the patients have complicating renal or cardiovascular disease. Resolution is usually slow and lags behind clinical improvement. An interstitial pattern may appear during resolution.

It is evident that there is a wide variety of roentgen patterns in this disease, so the diagnosis cannot be made on the basis of chest roentgenograms. However, the disease should be suspected in a patient with atypical pneumonia in whom roentgenograms show unilateral or bilateral, large, poorly marginated, rounded alveolar opacities that progress rapidly to involve one or more entire lobes.

The Pittsburgh pneumonia agent (Tatlockia micdadei, Legionella micdadei) was described in 1979. It is a gram-negative, weakly acid-fast bacillus that appears to be identical to the Tatlock organism isolated 37 years earlier. It has been recognized as a disease seen mainly in renal transplantation patients and others treated with high-dose corticosteroid therapy. However, it has also been reported94 in patients who were not immunosuppressed. Radiographic findings are those of an alveolar type of pneumonia, usually in one lobe, either segmental or subsegmental and nodular in appearance. In the compromised patient, it spreads very rapidly and occasionally cavitates. Pleural effusion is found in about 30% of patients. The organism is similar to L. pneumophila, and the two diseases are found simultaneously in a few patients. The diagnosis is made by lung biopsy.

Pulmonary Infection in the Compromised Host (Opportunistic Infections)

Diseases of the chest including opportunistic infections occurring in the immunocompromised host are discussed in Chapter 25.

Hospital-Acquired (Nosocomial) Pneumonias

Hospital-acquired pneumonias are important because the impaired resistance of the hospital patients renders them very susceptible to gram-negative bacilli such as P. aeruginosa, E. coli, and other Enterobacter species. Outbreaks of Staphylococcus, Klebsiella, Proteus, and other pneumonias have also been reported. Furthermore, the wide use of antibiotics has resulted in resistant pathogens that may also cause pneumonia. The lungs are involved in 10% to 30% of infections acquired in hospitals. In this patient population, mortality may be very high and every precaution must be taken to avoid contamination of respiratory therapy equipment, anesthesia machines, air-conditioners, and other devices used in patient care. Pseudomonas infection is particularly common in this group of patients, is very difficult to treat, and has a high mortality rate despite treatment with various combinations of antibiotics. Nosocomial pneumonia should be considered when a hospitalized patient develops leukocytosis, cough, or fever. In this situation, any new or increasing pulmonary opacity may represent pneumonia. There are no specific patterns for the various organisms involved, so the radiologist’s role is to note the disease and suggest the possibility of pneumonia.

Viral, Mycoplasmal, and Rickettsial Pneumonias

Mycoplasmal Pneumonia

Mycoplasma pneumoniae (the Eaton agent) pneumonia is responsible for a significant percentage of primary atypical pneumonia in children and young adults (15% to 20% or more). It probably accounts for almost 50% of pneumonias found in children younger than 16 years of age. The remainder of patients with primary pneumonia have disease caused by adenovirus, parainfluenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus, and probably other viruses. In many patients, the cause is not determined. Cold agglutinins are found in the serum of 50% to 60% of patients with Mycoplasma pneumonia. A titer of 1:32 or higher is considered positive and is usually found 10 to 14 days after onset of the symptoms. A high titer is usually present. Mycoplasmal pneumonia tends to occur in epidemics, as well as sporadically, so it is difficult to obtain meaningful figures as to relative frequency. The disease usually occurs in young, healthy adults. It is acute, mild, and self-limited in most instances but may be severe with widespread pulmonary disease. Occasional fatalities have been reported. The inflammatory exudate is sometimes more interstitial than in the bacterial pneumonias, but alveolar exudate, which contains fewer cells and more fluid than in the bacterial type, is also present. The onset of symptoms is gradual, and there is often a delay in the appearance of visible pulmonary density on roentgen examination for 2 or 3 days. Putman and colleagues108 described two groups of patients with different clinical and radiographic findings. One group with acute chest pain, cough, and fever developed segmental or lobar air-space disease. The other group had a more chronic course, were afebrile, and had no cough or chest pain. They developed interstitial changes and a reticulonodular or mixed pattern of focal air-space and interstitial disease. Others have noted less relation between symptoms and anatomic distribution.

Roentgen findings reflect the anatomic changes. Recognizable forms can be divided into several types:

Peribronchial or interstitial type. The findings in the peribronchial type consist of streaky densities extending outward from the hilum following the pattern of the vascular markings, limited to a single segment or affecting one or several lobes. Alveolar exudate may produce scattered patchy density as well as the linear shadows.

Bronchopneumonic type. The roentgen findings are similar to those described for bronchopneumonia and may be just as widespread. Opacities that are usually poorly defined and scattered may be noted in any lobe or segment and may be bilateral.

Segmental and lobar types. The findings are those of homogeneous density representing consolidation in a segment, several segments, or a lobe. Single-lobe involvement occurs in almost 50% of patients. Air bronchograms may be present. The appearance of the consolidation is similar to that found in S. pneumoniae lobar pneumonia. Pleural effusion occurs in about 20% of patients with this type of disease and is rare in the interstitial type.

Diffuse type. A bilateral reticulonodular pattern throughout both lungs. Pleural effusion is rare.

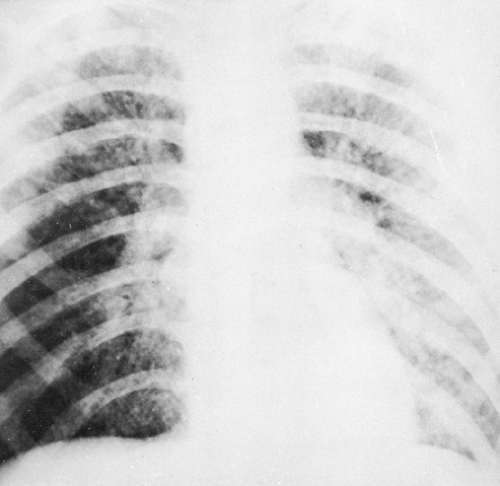

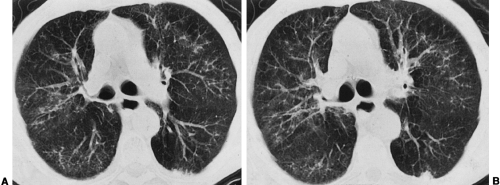

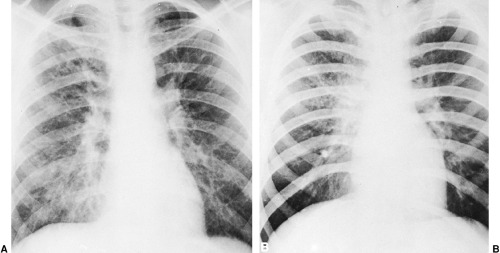

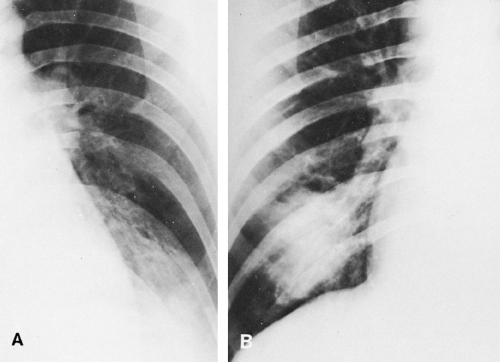

One or more of these gross anatomic types of the disease may be present in a single patient. There is a tendency for the disease to clear in one area and spread in another, often in the opposite lung. Atelectasis may be produced by bronchial obstruction and is frequently lobular and focal in type. Occasionally, a pneumatocele may result from check-valve obstruction and must be differentiated from lung abscess (see Fig. 24-7). Resolution is usually slow, and it is common to see persistent pulmonary lesions for a week or longer after the clinical findings have disappeared. Occasionally, the delay is considerably greater. Mycoplasmal pneumonia cannot be differentiated from viral infections of the lung, and when the distribution is segmental or lobar it is similar to bacterial pneumonia (Figs. 24-13, 24-14, and 24-15).

In the differential diagnosis, there are findings that help to differentiate mycoplasmal from bacterial pneumonia. They consist of the lack of pleural involvement, manifested by absence of elevation of the diaphragm and absence of pleural

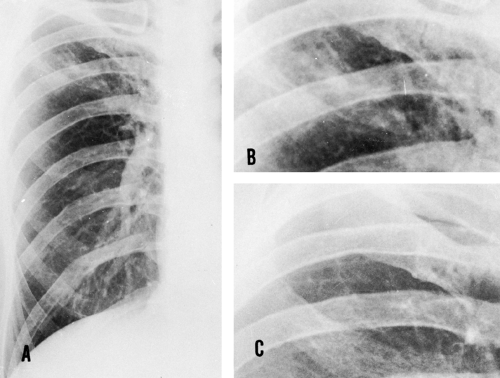

fluid in most cases. The delay in appearance of pulmonary disease after clinical onset is also helpful. The tendency to clear in one area and spread in another is more common in this disease than in bacterial pneumonia. Bilateral involvement is probably more common than in bacterial pneumonias, with disease often in one lower lobe and the opposite upper or middle lobe. However, because the roentgen pattern may vary widely, the diagnosis must be substantiated by clinical and laboratory findings (Fig. 24-16).

fluid in most cases. The delay in appearance of pulmonary disease after clinical onset is also helpful. The tendency to clear in one area and spread in another is more common in this disease than in bacterial pneumonia. Bilateral involvement is probably more common than in bacterial pneumonias, with disease often in one lower lobe and the opposite upper or middle lobe. However, because the roentgen pattern may vary widely, the diagnosis must be substantiated by clinical and laboratory findings (Fig. 24-16).

Adenovirus Pneumonia

There are 28 types of the adenovirus, which is a common cause of upper respiratory disease and may cause pneumonia, often in epidemics. The disease is usually more severe in infants and young children than in adults. The most common roentgenographic pattern is that of a widely scattered patchy or confluent disease, usually in a peribronchial distribution. Slow resolution is usually noted, with residual bronchiectasis in some children and obliterative bronchiolitis and other chronic lung disease in others. This virus also causes acute bronchiolitis with overinflation in infants and can cause unilateral hyperlucent lung (Swyer-James syndrome). Bronchiolitis can also be caused by other viruses such as the respiratory syncytial virus, rhinovirus, influenza virus, and parainfluenza virus, usually in children. It is unusual in adults and is rarely diagnosed. Although pulmonary involvement may be extensive, the acute illness may not be severe, particularly in adults.

Other Viral Pneumonias

Several viruses are capable of causing pneumonia, often in epidemics.24 A number of new viral diseases, including Ebola fever and Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome, have emerged in recent years as life-threatening epidemics.14 The roentgenographic findings of most viral pneumonias are similar to those described for mycoplasmal pneumonia, so the cause cannot be established on the basis of these findings alone. In some epidemics, the pericardium is involved, leading to effusion, often associated with pleural effusion as well. Often the virus is not definitely identified in these patients and the diagnosis is based on clinical findings. The disease usually is not as prolonged or severe as mycoplasmal pneumonia.

Epidemic influenza, which is a viral disease, may be associated with virus infection of the pulmonary parenchyma in addition to involvement of the tracheobronchial tree. Roentgen signs are variable, with findings often bilateral and extensive. Especially in severe epidemics of the past, the pneumonia was often of the interstitial type with hazy, strand-like densities radiating outward from the hila. These result in a coarse appearance of the bronchovascular pattern and irregular hilar thickening. In other patients, segmental or lobar consolidation may be present; it may be bilateral. A diffuse, patchy pattern resembling pulmonary edema has also been described. Pleural effusion is rare in uncomplicated influenza pneumonia. The diagnosis is often made from clinical findings during an epidemic. The roentgen

changes are then largely confirmatory, but radiographic examination is useful to observe the course of the pulmonary parenchymal disease. A complicating staphylococcal pneumonia may also occur, particularly in epidemics in which influenza is severe. Most fatalities are caused by this complication.

changes are then largely confirmatory, but radiographic examination is useful to observe the course of the pulmonary parenchymal disease. A complicating staphylococcal pneumonia may also occur, particularly in epidemics in which influenza is severe. Most fatalities are caused by this complication.

Herpes simplex pneumonia may occur in neonates and immunocompromised hosts. It is a severe, often fatal disease in neonates, with an initial interstitial pattern progressing to coalescent air-space densities and a diffuse alveolar “white-out” of both lungs in the fatal cases. The pathology is that of a necrotizing hemorrhagic pneumonia. The disease is usually widely disseminated in these neonates.

Pneumonia associated with chickenpox (varicella) is believed by some to be viral in origin and has been reported occasionally. It usually occurs in adults with severe chickenpox. Roentgen findings consist of widespread, poorly defined, patchy or nodular densities associated with an increase in parahilar markings and occasionally enlargement of the hilar nodes (Fig. 24-17). Densities are most marked in the parahilar areas and at the bases. Individual nodules are generally round but are poorly defined peripherally. There is often considerable change in the roentgen findings from day to day, because the densities are transitory. Clearing is usually slow, however. In patients with fatal disease, pulmonary involvement may be virtually total, with little if any visible aerated lung. In rare instances, scattered small calcifications result from varicella pneumonia in adults. No hilar node calcification is observed. It is entirely possible for bacterial pneumonia to appear in patients with these various viral diseases and there is no way to differentiate the cause on chest radiographs.

Measles (rubeola) is occasionally associated with pneumonia caused by the virus.110 Pneumonia caused by other

organisms sometimes complicates measles, however, so roentgen differentiation is not possible. The measles virus causes reticuloendothelial involvement resulting in hilar and mediastinal adenopathy. The virus may also involve the lung to produce an interstitial process that is manifested as a widespread reticular type of reaction, with predilection for the bases. Consolidation of lung with varying degrees of atelectasis most probably represents a complicating bacterial pneumonia.

organisms sometimes complicates measles, however, so roentgen differentiation is not possible. The measles virus causes reticuloendothelial involvement resulting in hilar and mediastinal adenopathy. The virus may also involve the lung to produce an interstitial process that is manifested as a widespread reticular type of reaction, with predilection for the bases. Consolidation of lung with varying degrees of atelectasis most probably represents a complicating bacterial pneumonia.

Atypical measles pneumonia occurs in adolescents and young adults after previous “incomplete” immunity conferred by killed rubeola virus vaccine. It is probably a hypersensitivity response in incompletely immunized patients. The pneumonia is usually segmental and bilateral but may involve most or all of a lobe. Other patterns include “round” pneumonia, diffuse perihilar opacity, and multiple nodules. Pleural effusion and hilar adenopathy occur in about one third of patients. Usually the patients have the skin eruption of measles. The acute pneumonia usually clears promptly, but rarely a nodule persists for 1 to 2 years.83

Pneumonic involvement may occur with several other viral diseases, including smallpox, lymphocytic choriomeningitis, and cytoplasmic inclusion disease in infants and children. There is nothing characteristic about the roentgen appearance of the pneumonia associated with these diseases except that the pneumonia is usually bilateral and often extensive. Cytomegalovirus infection is the most common viral infection in immunosuppressed patients. In patients having cytomegalovirus disease, nodules have been reported involving the outer one third of the lungs. Lung biopsy may be necessary to establish the diagnosis.

Hantavirus caused an outbreak of a new fatal pneumonia in young, otherwise healthy persons living in the southwestern United States in 1993. Since then, an increasing number of cases have been identified outside of that area as well. The virus is spread by rodents; inhalation of aerosolized, virus-infected rodent droppings is the mode of transmission to humans. Patients present with a prodrome of fever and flu-like symptoms, followed by cough, increasing dyspnea, and rapid progression to fulminant pulmonary failure, which is often fatal.58

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree