Clinical Presentation

The patient is a 62-year-old man who has been under a physician’s care for fainting spells for the last 6 months. He has also had symptoms of numbness in his shoulders, arms, and hands, which has become worse over the last few years. He also has paresthesias and numbness on the right side of his neck and face. The patient describes problems with balance and urinary urgency. On neurologic examination, the patient has some difficulty with tandem gait. His strength is normal. He has numbness on the right side from C2 through C4 and has an absent right biceps reflex.

Imaging Presentation

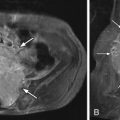

Sagittal T1- and T2-weighted magnetic resonance (MR) imaging obtained demonstrates a long-segment region of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)–signal intensity within the cervical spinal cord from C2-T2. There is also pointing of the cerebellar tonsil, which extends through the foramen magnum consistent with Chiari type I malformation with syringomyelia ( Fig. 15-1 ) .

Discussion

The Chiari malformation is characterized by inferior herniation of the cerebellar tonsils through the foramen magnum. The various types of Chiari malformation, I to III, are a continuum of posterior fossa hindbrain development. The general consensus is that the main abnormality in Chiari I is underdevelopment of the occipital bone with an otherwise normal posterior fossa brain volume.

The Chiari I malformation is usually congenital but can, on occasion, be acquired. Symptoms of Chiari malformation do not often arise until the patient is in the late thirties. Depending on the degree of cerebellar tonsillar herniation, the size of the foramen magnum, and which structures may be compressed, the presentation of a Chiari malformation can vary from no symptoms to very severe. The clinical presentation of Chiari I can be related to direct compression of the brainstem or spinal cord or to cerebrospinal fluid disturbances such as hydrocephalus. Headache, the most frequent symptom, might be the only manifestation of Chiari I or it can be absent altogether. The Chiari I headache is often occipitosuboccipital and may worsen with Valsalva maneuver/cough, change in posture, or physical exertion. Other symptoms include neck pain, balance problems, muscle weakness, numbness, or other abnormal feelings in the arms or legs, dizziness, vision problems, difficulty swallowing, ringing or buzzing in the ears, hearing loss, vomiting, insomnia, or depression.

The incidence of Chiari I malformation, with tonsillar herniation greater than 5 mm through the foramen magnum, is approximately 0.5% to 0.75%. However, if one includes tonsillar herniation of 2 mm below the foramen magnum, then the sensitivity of predicting symptomatic patients is 100% with a specificity of 98.5%. If the lowest extent of the tonsils is 3 mm, then the sensitivity is 96% with a specificity of 99.5%. Therefore, borderline Chiari I is diagnosed radiographically with 3 to 5 mm of caudal descent of the cerebellar tonsils. One can be more definite in the diagnosis if there is 5 mm or more descent, pointed tonsils, and/or crowding at the craniocervical junction. Most series report a slight female preponderance for Chiari I.

A syringomyelia, an abnormal collection of fluid within the spinal cord, occurs in approximately 14% to 75% of patients with Chiari I. Cavitation may occur in the spinal cord in 20% to 40%, and 60% to 90% of symptomatic patients have an associated syrinx. There have been many hypotheses regarding why a syrinx cavity develops in Chiari patients. Some have proposed that CSF is unable to pass through the fourth ventricle because of the crowding of the posterior fossa. The systolic pulsations of CSF are then redirected from the fourth ventricle to the central canal of the spinal cord (“water-hammer” effect) with the creation of a syrinx and progressive cavitation. Another theory suggests a ball-valve obstruction at the foramen magnum with a pressure difference created between the intracranial contents and spinal canal during patient coughing or Valsalva maneuver. During coughing or Valsalva maneuver, fluid that would normally be forced into the head may be directed into the spinal cord through extracellular pathways because of obstruction at the foramen magnum. There are also reported cases of spontaneous regression of Chiari-associated syrinx.

Skeletal anomalies are often seen in conjunction with Chiari I malformation, including scoliosis in 40% to 60%, basilar invagination in 25% to 50%, and Klippel-Feil in 5% to 10%. The posterior fossa is small and there may be a short clivus.

Chiari II malformations have displacement of the cerebellar vermis and tonsils into the spinal canal with caudal displacement of the brainstem and elongation of the fourth ventricle. Type III malformations are rare and are characterized by herniation of the medulla and cerebellum into a high cervical meningocele. Chiari II and III malformations are readily recognized early in life due to their associated meningoceles. Chiari I malformations are frequently undetected until later in childhood or adulthood.

Imaging Features

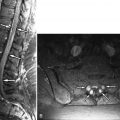

On computerized tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the cerebellar tonsils should be at least 5 mm below the foramen magnum for the radiographic criterion of Chiari I to be fulfilled. The foramen magnum is delineated by a line drawn between the midpoint of the anterior border of the foramen magnum/tip of the clivus (basion) and midpoint of the posterior border of the foramen magnum (opisthion) ( Fig. 15-2 ) . The shape of the inferior tonsils is pointed or pegged (see Fig. 15-1 ). The fourth ventricle is normal in position but may be elongated ( Fig. 15-3 ) . A syringohydromyelia is identified in many patients. The syrinx cavity is best imaged with MRI. The syrinx has the imaging characteristic of CSF and therefore demonstrates decreased T1 signal, increased T2 signal, and no enhancement ( Fig. 15-4 ) . MR cinematic phase-contrast (Cine PC) imaging can be performed to evaluate whether there is normal CSF pulsation ventral and dorsal to the cervicomedullary junction either before or after surgery ( Fig. 15-5 ) .