Cholecystitis

Oleg M. Teytelboym

Etiology and Epidemiology.

Acute cholecystitis is the most common cause of acute right upper quadrant pain. Most cases are caused by cystic duct obstruction from an impacted gallstone. Approximately one third of the patients with gallstones will develop cholecystitis. Acalculous cholecystitis accounts for 5-10% of acute cholecystitis cases and typically occurs in critically ill patients who have not been fed orally for a prolonged period of time. In patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), acute cholecystitis can be caused by infection with cytomegalovirus, cryptosporidium, or microsporidium.

Before widespread use of imaging, up to 22% of patients who were surgically explored for suspected cholecystitis did not have it. Imaging is also used to look for emergent complications of acute cholecystitis, such as gangrene (2-38% of cases) or perforation (3-15%).

Symptoms and Signs.

Acute cholecystitis usually presents with sudden onset of right upper quadrant or epigastric pain and tenderness, frequently precipitated by a fatty meal. Most cases subside spontaneously due to antegrade or retrograde stone passage. Attacks lasting more than 1 day are unlikely to resolve spontaneously. Most patients experience nausea and vomiting. Fever and mild leukocytosis are common. Mild elevation of liver function tests is not unusual; however, persistent or significant elevation suggests choledocholithiasis.

Differential Diagnosis.

Clinical presentation of acute cholecystitis can be mimicked by pancreatitis, appendicitis, peptic ulcer disease, gastroesophageal reflux, hepatitis, liver abscess, liver neoplasm, right lower lobe pneumonia, and cardiac disease.

Complications

Gangrenous or necrotizing cholecystitis occurs when gallbladder distension impedes venous drainage, leading to ischemia and transmural necrosis. Clinical and imaging findings are frequently indistinguishable from uncomplicated acute cholecystitis and the diagnosis is often not made preoperatively. These patients commonly require an open cholecystectomy, with 8-75% conversion rates from laparoscopic to open cholecystectomy.

Emphysematous cholecystitis results from infection with gas-forming bacteria, typically occurring in elderly or diabetic patients.

Gallbladder perforation is a life-threatening complication of cholecystitis with up to 24% mortality. Perforation can lead to generalized peritonitis, pericholecystic abscess, or enterohepatic fistula, often to the duodenum or common bile duct (CBD). The presence of gangrenous and emphysematous cholecystitis significantly increases the risk of perforation.

Choledocholithiasis results from gallstone passage into the CBD and may lead to biliary obstruction, pancreatitis, and ascending cholangitis.

Mirizzi syndrome describes CBD obstruction by inflammation related to a gallstone impaction in the cystic duct.

Indications.

Ultrasonography is the preferred modality for evaluation of suspected acute cholecystitis because of ready availability and high accuracy. It can also provide additional information about nonbiliary pathology in cases where the gallbladder is found to be normal.

Protocol.

If possible, the examination should be performed after 6-hour fast to ensure adequate distension of the gallbladder. The gallbladder should be examined with the patient in supine and left posterior oblique positions. If cholelithiasis is present, every effort should be made to evaluate for stone impaction in the gallbladder neck or cystic duct by turning or standing the patient to determine if the gallstone is mobile.

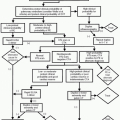

Possible Findings (Fig. 28-1)

Sonographic Murphy’s sign (maximal tenderness over the sonographically localized gallbladder) is the most reliable finding for diagnosis of acute cholecystitis. In the presence of cholelithiasis, this sign is highly suggestive of acute cholecystitis with 92% positive-predictive value. Absence of significant gallbladder tenderness has 72% negative-predictive value for acute cholecystitis.

Gallbladder wall hyperemia on Doppler ultrasound can be very helpful for diagnosis of acute cholecystitis with 98-100% specificity and 30-95% sensitivity.

Less specific signs of acute or chronic cholecystitis include cholelithiasis, gallbladder dilatation, wall thickening (>3 mm), pericholecystic fluid, and sludge.

Asymmetric gallbladder wall thickening or intraluminal membranes suggest gangrenous cholecystitis. The sonographic Murphy’s sign may be absent, possibly due to denervation of the gallbladder wall by gangrenous changes.

Hyperechoic foci with “dirty shadowing” in the gallbladder wall or lumen represent gas and are diagnostic for emphysematous cholecystitis. This appearance can be confused with gallbladder wall calcifications. Definitive diagnosis can be established with computed tomography (CT).

Pericholecystic abscess or extraluminal stones suggest gallbladder perforation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree